Abstract

This review aims to comprehensively examine the historical development, molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of checkpoint inhibitors in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN). Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck represents a significant global health challenge as the 7th most common malignancy worldwide. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways have emerged as promising therapeutic approaches. Current evidence supports the use of ICIs in the recurrent/metastatic (R/M) setting, while data for neoadjuvant and adjuvant applications is evolving. Pembrolizumab monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy has demonstrated survival benefits in PD-L1-positive R/M SCCHN, while nivolumab has shown efficacy in the second-line setting. Results from trials combining ICIs with radiotherapy have been mixed, with several phase III studies failing to meet primary endpoints.

The integration of ICIs has transformed the treatment landscape for R/M SCCHN, while the ongoing research continues to define their optimal use in earlier disease settings and in novel therapeutic combinations. Future directions include exploring combination strategies with targeted therapies, identifying predictive biomarkers beyond PD-L1 expression, and developing immunotherapy approaches tailored to HPV-positive vs. HPV-negative disease.

Keywords: CTLA-4, PD-1, PD-L1, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, checkpoint inhibitors

Introduction

Head and neck cancer has emerged as a global health challenge, representing the 7th most common malignancy worldwide, with an annual incidence of 890,000 cases and around 450,000 deaths in 2022.1 Squamous cell carcinomas constitute approx. 90% of all head and neck cancers (SCCHN).2 The prevalence of SCCHN is significantly higher in developing countries.3 Environmental carcinogens, particularly tobacco and alcohol, are responsible for 75–85% of SCCHN cases.4 The molecular pathogenesis of SCCHN frequently involves mutations in the tumor protein p53 gene (TP53), induced by xenobiotics that interfere with DNA synthesis and repair mechanisms. TP53 mutations are associated with shorter overall survival (OS), potential therapeutic resistance and increased recurrence rates.5 Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection represents a second major etiological factor, particularly in oropharyngeal cancers. HPV-positive patients constitute approx. 30–35% of oropharyngeal cancer cases and 6% of all oropharynx cancers. In contrast to TP53-mutated tumors, HPV-positive disease is associated with significantly better outcomes.6, 7 Furthermore, the role of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection in the development and progression of tumor cells has been proven in head and neck cancers, such as nasopharyngeal cancer.8 In case of cytomegalovirus (CMV), oncogenic potential in head and neck cancer is unclear.9 Additional risk factors include radiation exposure, poor oral hygiene, inadequate nutrition, betel nut chewing, ill-fitting dentures, and certain genetic syndromes, such as Fanconi anemia, ataxia–telangiectasia, Bloom’s syndrome, Li–Fraumeni syndrome, and dyskeratosis congenita.8 The association between periodontal disease,9 gut microbiota10 and cancer risk has also been postulated.

The molecular mechanisms of head and neck carcinogenesis comprise genetic and epigenetic alterations, which lead to the malignant neoplastic process. Among genetic factors, the most important are mutated oncogenes p53 or RAS, as well as the inactivation of tumor suppressor proteins like p16INK4a.11 Uncontrolled proliferation and apoptosis evasion – typical for cancer – are connected with such pathways as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR), Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), and Wnt/β-catenin.12 DNA methylation, histone acetylation and methylation, as well as microRNA-mediated regulation, are among the most probable epigenetic factors involved in the tumorigenesis of head and neck cancers.13

While advances in diagnostic techniques, including artificial intelligence (AI)-based approaches and neural networks, have improved early detection,14 novel therapeutic strategies are needed for advanced-stage disease to complement or replace conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have emerged as one of the most promising approaches in the systemic treatment of SCCHN. In patients who may potentially benefit from ICI therapy, programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression is evaluated using the combined positive score (CPS), defined as the number of PD-L1-positive cells (tumor cells, lymphocytes and macrophages) divided by the total number of tumor cells, multiplied by 100.15, 16

Despite the growing amount of literature on immunotherapy in SCCHN, most of the existing reviews focus either on the general mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibition or on specific clinical trials, without integrating historical context, biomarker-driven strategies and the emerging therapeutic combinations. There is a lack of comprehensive narrative reviews that would bridge the evolution of checkpoint inhibitors with current clinical applications and future directions in SCCHN treatment.

This review addresses that gap by aiming to provide a comprehensive overview of the historical development and current vision of checkpoint inhibitor therapy in SCCHN, highlighting key clinical trials, the emerging therapeutic targets and future directions in immunotherapy.

Material and methods

The literature search was performed using the PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science electronic databases. We included peer-reviewed articles published between 1982 and May 2024, written in English, that addressed the use of checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of SCCHN. Both clinical trials and high-quality narrative or systematic reviews were considered.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: studies involving adult patients with SCCHN; articles discussing checkpoint inhibitors as monotherapy or in combination; reviews and clinical trials with clearly reported outcomes. Exclusion criteria were as follows: non-English publications; case reports; editorials; studies focusing on non-squamous histology or unrelated cancer types.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) – biological basis and development

The field of cancer immunotherapy was revolutionized by the pioneering work of Tasuku Honjo from Kyoto University, Japan, and James Patrick Allison from MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, who were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 2018 for their discovery of cancer therapy through the inhibition of negative immune regulation.17

PD-1/PD-L1 pathway

Honjo’s research group first isolated the complementary DNA (cDNA) of programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1)18 and demonstrated its role as a negative regulator of B cell responses, particularly in antibody class switching.19 PD-1 is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and the cluster of differentiation (CD)28/cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) subfamily, expressed on CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).20 PD-1 expression is induced by cytokines interleukin (IL)-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21.21 Additionally, ICIs can influence the cytokine environment; for example, avelumab reduces STAT3 expression, affecting interleukin -17 receptor A (IL-17RA) and CD15.22

The characteristic feature of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily is a single Ig V-like domain in the extracellular region, which is crucial for binding to ligands.23 The PD-1 structure comprises 3 parts: a ~20-amino acid stalk; a transmembrane domain; and a cytoplasmic tail with 2 tyrosine-based signaling motifs. The N-terminal extremity sequence contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM), called VDYGEL, which recruits SH2 domain-containing phosphatases.24 The elements responsible for the inhibitory function of PD-1, the sequence TEYATI and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM), are located at the C-terminal extremity.25

The ligation of PD-1 leads to the formation of PD-1/T-cell receptor (TCR) inhibitory micro-clusters, and recruits SHP1/2. Simultaneously, ITIM and ITSM sequences are dephosphorylated by Src-family tyrosine kinases. The intracellular pathways Ras GTPase/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (RAS/MEK/ERK) and PI3K/AKT are activated through the recruitment of SHP1 and SHP2. SHPs can also block protein kinase C theta (PKC-θ) and ZAP-70.26 Consequently, this sequence arrests the cell cycle and suppresses T cell activation through the induction of apoptosis, the reduction of proliferation and the inhibition of cytokine secretion.27, 28

Programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1), also known as protein B7-H1 or CD274, was identified through the collaboration of the Honjo and Freeman research groups.29 This ligand is encoded on chromosome 9p24.1 in the CD274 gene,30 and is expressed on the surface of T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, mesenchymal stem cells, and bone marrow-derived mast cells.31 PD-L1 binding can increase T-cell proliferation, decrease IL-2 secretion and increase IL-10 secretion.32 PD-L2 (CD273 or B7-DC) is encoded by the PDCD1LG2 gene on chromosome 9p24.1.32 This protein was isolated by Latchman and colleagues,33 and is expressed on activated CD4+ or CD8+ cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and bone marrow-derived mast cells.34, 35 The interaction between PD-L1 located on tumor cells and PD-1 on T cells can diminish the immunological response to neoplastic disease by suppressing T cell activation. Multiple cytokines are identified as biomarkers for the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma.36

The rapid development of PD-1 inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab, dostarlimab, cemiplimab) and PD-L1 inhibitors (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) has revolutionized the systemic treatment of various cancers.36

CTLA-4 pathway

In 1991, James Patrick Allison, the second “father of immunotherapy,” discovered CTLA-4 and demonstrated its inhibitory role in anti-tumor T-cell activity.37, 38 In 1995, CTLA-4 was identified as a negative regulator of T-cell activation.39 The receptor, also known as CD152, is a member of the Ig superfamily responsible for recruiting phosphatases to TCRs and attenuating their signals.40 CTLA-4 is also found in regulatory T cells and dendritic cells.41 In 1996, Allison demonstrated that the blockade of CTLA-4 could enhance anti-tumor immune responses, opening a second avenue for ICI therapy.42 In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first anti-CTLA-4 antibody, ipilimumab, for the treatment of metastatic melanoma.43 Subsequently, CTLA-4 blockade has become an integral component of therapeutic regimens for SCCHN.44 The emerging data suggests that another antibody from this group, tremelimumab, is being investigated for application in SCCHN therapy.45

Neoadjuvant therapy before definitive surgery

The anatomical location of head and neck cancers often necessitates disfiguring surgical or radiotherapeutic procedures, which can significantly impair quality of life after radical therapy. The implementation of neoadjuvant or concurrent (with radiotherapy) systemic treatment using ICIs could potentially reduce complications and improve cosmetic outcomes, thereby enhancing quality of life and prolonging disease-free survival (DFS). Furthermore, tumor downstaging may render previously unresectable lesions amenable to surgical resection and reduce the risk of positive surgical margins. Upfront surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy were compared in a retrospective study.46

Recent years have witnessed numerous investigations focusing on neoadjuvant ICI therapy. One of the earliest studies was the phase II trial NCT02296684, in which 14 patients received 2 doses of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab before surgical intervention for head and neck cancer.47 A substantial pathological tumor response (pTR) (≥50%) was observed in 45% of participants. Single-cell analysis of 17,158 CD8+ T cells revealed that the responding tumors had clonally expanded putative tumor-specific exhausted CD8+ TILs with a tissue-resident memory program, characterized by high cytotoxic potential (CTX+) and ZNF683 expression. Five weeks after therapy, the effect was consistent with the activation of the pre-existing CTX+ZNF683+CD8+ TILs and associated with high numbers of CD103+PD-1+CD8+ T cells infiltrating pre-treatment lesions. In non-responders, the absence of ZNF683+CTX+ TILs correlated with the subsequent accumulation of highly exhausted clones. These observations suggest the important role of the pre-existing ZNF683+CTX+ TILs in the primary mechanism of response following neoadjuvant treatment.47

Another PD-1 inhibitor, nivolumab, was evaluated in patients with resectable HPV-positive and HPV-negative SCCHN in the phase I/II clinical trial CheckMate 358.48 This study included 26 HPV-positive and 26 HPV-negative participants who received nivolumab 240 mg intravenously on days 1 and 15, with surgery scheduled by day 29. Radiographic responses were achieved in only 12.0% of HPV-positive and 8.3% of HPV-negative patients, with pathological responses in 5.9% and 17.6% of participants, respectively. A partial pathological response (pPR) was confirmed in only one HPV-positive patient, with no complete pathological responses (pCR) observed. Despite these modest response rates, treatment-related adverse events of any grade occurred in 73.1% of HPV-positive patients and 53.8% of HPV-negative patients, with grade 3–4 events in 19.2% and 11.5%, respectively.48

Several trials also investigated the combination of ICIs with chemotherapy. For example, a phase II clinical trial evaluated a single dose of durvalumab with or without tremelimumab before resection.49 The study enrolled 48 patients, randomized into 2 arms: 24 patients received the combination therapy; and 24 received durvalumab monotherapy. From the entire cohort, 45 underwent surgical resection followed by postoperative chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy based on multidisciplinary assessment, with 1-year consolidation with durvalumab. Distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS) was significantly better in patients treated with combination therapy as compared to the monotherapy arm. Artificial intelligence-powered analysis demonstrated that combination therapy reshaped the tumor microenvironment toward immune-inflamed phenotypes, in contrast to monotherapy or cytotoxic chemotherapy. The authors concluded that a single dose of durvalumab with tremelimumab before resection followed by postoperative chemoradiotherapy could benefit patients with resectable head and neck cancers.49

In another phase II randomized trial, neoadjuvant nivolumab monotherapy was compared to ICI doublet therapy – ipilimumab plus nivolumab or relatlimab plus nivolumab – for 4 weeks prior to surgery.50 Participants were stratified by p16, PD-L1 and lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) expression, assessed with immunohistochemistry. Of the 41 patients enrolled, only 33 were evaluable for analysis (25 with oral cavity cancer, 5 with oropharyngeal cancer, and 3 with laryngeal cancer). In the doublet arms, pathological responses were more frequent (nivolumab/relatlimab: 11/13 and nivolumab/ipilimumab: 6/10) than in the nivolumab monotherapy arm (6/10). The combination arms were also associated with more partial (>50%) or major (>90%) pathological responses than monotherapy. There was no association between the RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) response, PD-L1 or LAG3 expression and the pathological response in the nivolumab/relatlimab arm; however, more patients with combined positivity had a >50% response (4 vs. 0). Across the entire trial, there were no serious study drug-related adverse events. The authors highlighted the promising nature of this approach, noting that the trial continues to enroll patients for further evaluation.50

Neoadjuvant ICI therapy has also been combined with chemotherapy or other systemic treatment. Toripalimab (a PD-1 inhibitor) in combination with albumin-bound paclitaxel/cisplatin (TTP) was evaluated in a single-arm prospective study (Illuminate Trial) in patients with locally advanced resectable oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC).51 The protocol enrolled 20 patients with clinical stage III or IVA OSCC, who received 2 cycles of chemoimmunotherapy followed by radical surgery and risk-adapted adjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy. All patients underwent microscopically radical surgical procedures (R0) with a low incidence of significant adverse events during neoadjuvant therapy (only 3 patients with grade 3 or 4 events). Major pathological responses (MPRs) were observed in 60% of the clinical group, including 30% with pCR. A favorable clinical response was associated with positive PD-L1 expression (>10%). The DFS rate was 90% and the OS rate was 95% after 26 months of follow-up.51

In another single-arm phase II trial, neoadjuvant therapy with 3 cycles of paclitaxel, cisplatin and toripalimab was tested in 27 patients with locally advanced laryngeal/hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.52 After neoadjuvant therapy, participants with a complete or partial response of the primary tumor received concurrent chemoradiation followed by maintenance toripalimab. In other cases, patients underwent surgery followed by adjuvant chemoradiation and maintenance toripalimab. The primary endpoint was the larynx preservation rate at 3 months post-radiation. The overall response rate (ORR) was 85.2%, with an 88.9% post-radiation larynx preservation rate. After 1 year of follow-up, the OS rate was 84.7%, the progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 77.6%, and the larynx preservation rate was 88.7%.52

Despite some promising results in clinical trials, neoadjuvant therapy has not yet been incorporated into clinical practice based on the guidelines published by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)53 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).54 The comparison of clinical trials focused on the neoadjuvant therapy for SCCHN is presented in Table 1.

Adjuvant immunotherapy after definitive surgery

Definitive surgery, alongside definitive radiotherapy, remains a primary therapeutic modality for head and neck cancers. In many cases, even after radical procedures, patients require adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.55 Adjuvant ICI therapy represents a potential strategy to improve prognosis, prolong DFS and provide an alternative option for platinum-ineligible patients requiring adjuvant treatment.

In an open-label, multi-institutional phase II clinical trial, patients with recurrent, resectable SCCHN received 6 adjuvant nivolumab cycles after salvage surgery.56 Adjuvant nivolumab following salvage surgery was well-tolerated and demonstrated improved DFS as compared to historical controls. There was no significant difference in DFS between PD-L1-positive and PD-L1-negative patients; however, there was a non-significant trend toward improved DFS in patients with high tumor mutational burden (p = 0.083).56

In another phase II trial (ADJORL1), patients with recurrent SCCHN or second primary tumors in the previously irradiated areas underwent surgery with curative intent, followed by adjuvant nivolumab for 6 months.57 A 2-year DFS was 46.6%, and a 2-year OS was 67.3%. Severe adverse events were reported in 19% of participants. The authors concluded that the 2-year DFS and OS outcomes were favorable when compared with historical data from reirradiation trials.57

In the PATHWay trial, high-risk SCCHN patients who had completed definitive treatment received adjuvant pembrolizumab therapy for 1 year.58 ICI therapy improved PFS in 2 subgroups: post-salvage surgery patients (HR (hazard ratio): 0.34; 80% CI (confidence interval): 0.18–0.67; p = 0.016); and those with multiple recurrences/primaries (HR: 0.48; 80% CI: 0.27–0.88; p = 0.057). Severe adverse events were noted in 6% of participants.58

Based on these studies, there appears to be a potential role for ICI therapy in the adjuvant setting after definitive surgery; however, larger, multi-center clinical trials are necessary to confirm these findings. The comparison of clinical trials focused on the adjuvant therapy for SCCHN is presented in Table 2.

Immunotherapy in combination with definitive (radical) radiotherapy

Radiation therapy (RT) is an established method for both radical and palliative management of head and neck cancer. Radiation therapy can be administered alone, concomitantly/concurrently, or sequentially after induction chemotherapy. The most common technique is intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) using contemporary computer-based planning and radiation delivery with or without simultaneous integrated boost (SIB). Radiation therapy may also be considered as adjuvant therapy (with or without chemotherapy) after primary surgical treatment, or in cases where surgery could be harmful or unacceptable to the patient, and for the functional preservation of critical structures such as the larynx.59, 60

The current standard of care includes the enhancement of standard RT with concomitant therapy, such as weekly cisplatin and platinum combined with 5-fluorouracil61, 62 or cetuximab.63, 64, 65, 66 Induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy may also be considered in cases of advanced locoregional disease.67 Despite the availability of multiple clinical options, novel therapeutic approaches could potentially improve prognosis and treatment outcomes. One of the most promising strategies is the application of ICIs before concomitant or concurrent therapy (the neoadjuvant approach).

The phase III JAVELIN Head and Neck 100 trial evaluated adjuvant 12-month avelumab therapy vs. placebo in 697 patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer after definitive cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy.68 The trial was terminated prematurely, as the boundary for futility had been crossed. The initial results showed a HR of 1.21 (95% CI: 0.93–1.57) and 1.31 (95% CI: 0.93–1.85) for PFS and OS, respectively.68

Another trial with avelumab, GORTEC-REACH, included 2 patient populations: cisplatin-fit patients who received standard-of-care cisplatin-based chemoradiation; and cisplatin-unfit patients who received weekly cetuximab and avelumab concurrently with radiation.69 Both treatment regimens were followed by avelumab for 12 months vs. the standard of care. This trial was also negative, as the primary endpoint of improved PFS was not met for either cohort. The PFS HR was 1.27 (95% CI: 0.83–1.93) for the cisplatin-fit cohort, and the PFS HR at 2 years was 0.85 (p = 0.15) for the cisplatin-unfit cohort.69

In the KEYNOTE-412 study, adjuvant pembrolizumab added after concurrent cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy was compared to placebo in 804 patients from 130 medical centers.70 Although the trial showed a favorable trend, there was no statistically significant benefit for the pembrolizumab arm (HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.68–1.03). Even in the subpopulation with high PD-L1 expression (CPS ≥ 20), neither the median PFS nor OS were reached in either arm. The investigators reported neutropenia, stomatitis, anemia, dysphagia, lymphopenia, pneumonia, acute kidney injury, and febrile neutropenia as significant adverse events. The authors concluded that the addition of pembrolizumab to chemoradiotherapy did not significantly improve event-free survival (EFS) as compared to placebo in a molecularly unselected locally advanced SCCHN population.70

The preliminary results of maintenance nivolumab therapy following definitive chemoradiotherapy showed an encouraging safety profile and some significant improvement in OS and PFS for patients with intermediate-risk HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer that had spread to nearby tissue or lymph nodes. However, phase III of the EA3161 trial is ongoing.71 Another ongoing trial, NRG-HN005, will evaluate the effectiveness and safety of de-intensified radiation therapy in combination with cisplatin or immunotherapy with nivolumab in patients with early-stage, HPV-positive, non-smoking-associated oropharyngeal cancer.72

ICI therapy can also be administered as adjuvant treatment after definitive radiotherapy, as demonstrated in the phase III IMvoke010 trial with atezolizumab.73 This study included 406 patients with locally advanced SCCHN (stage IVa or IVb) without disease progression after radical chemoradiotherapy. Participants were randomized to receive 1 year of atezolizumab or placebo. The trial was negative, showing no difference in OS between the arms.73 In contrast, the phase III NIVOPOSTOP GORTEC 2018-01 trial demonstrated statistically significant improvement in DFS in the nivolumab arm as compared to placebo after definitive chemoradiotherapy, although complete data presentation is still pending.74 A trial testing the combination of atezolizumab with cetuximab after chemoradiotherapy in high-risk head and neck cancer is currently enrolling participants.75 Another approach combines neoadjuvant radiotherapy with ICIs before radical surgical resection.76 In the phase II KEYNOTE-689 trial, neoadjuvant pembrolizumab was followed by surgical tumor ablation, and subsequently by postoperative (chemo)radiation. Furthermore, participants with high-risk pathology (positive margins and/or extranodal extension) received adjuvant pembrolizumab. Results were presented as pTR: pTR-0 < 10%; pTR-1 10–49%; and pTR-2 ≥ 50%. From the entire study population, 22% of patients had pTR-1, 22% had pTR-2, and none had pTR-3. After 1 year, 16.7% of participants with high-risk pathology experienced disease relapse.76 The phase III IMSTAR-HN trial, evaluating nivolumab monotherapy or combined with ipilimumab vs. the standard of care in resectable SCCHN,77 and the CompARE trial with durvalumab in patients with intermediate and high-risk oropharyngeal cancer78 are currently randomizing participants. The comparison of clinical trials focused on immunotherapy in combination with definitive (radical) radiotherapy for SCCHN is presented in Table 3.

ICI therapy in metastatic or relapsed head and neck cancer

ICI therapy in the treatment of recurrent/metastatic (R/N) head and neck cancer has established a position in routine clinical practice, as confirmed by the guidelines of ESMO53 and NCCN.54 Multiple clinical trials have led to the routine evaluation of PD-L1 expression through CPS, defined as the number of PD-L1-positive cells (tumor cells, lymphocytes and macrophages) divided by the total number of tumor cells, multiplied by 100.

The initial investigation was the phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 trial, which first suggested the manageable toxicity and promising anti-tumor activity of pembrolizumab in patients with R/N SCCHN.79 Subsequently, the single-arm phase II KEYNOTE-055 study evaluated pembrolizumab therapy in 171 patients (CPS ≥ 50 in 48 patients) with R/N SCCHN refractory to platinum-based therapy and cetuximab.80 Of these patients, 82% were PD-L1-positive and 22% were HPV-positive. The ORR was 16%, with a median duration of response (DoR) of 8 months. The median PFS was 2.1 months, and OS was 8 months. Adverse events occurred in 64% of patients, but only 15% experienced grade 3 or higher events, with fatigue, hypothyroidism, nausea, and increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) being most common. Statistical analysis revealed that HPV-positive patients demonstrated higher 6-month OS (72%) as compared to 55% in the HPV-negative subgroup; however, ORR and PFS were similar. The ORR was associated with the PD-L1 expression status (18% for CPS ≥ 1 and 27% for CPS ≥ 50).80

Following these preliminary findings, pembrolizumab demonstrated its value in the phase III KEYNOTE-048 trial.81 According to the protocol, participants were randomized to 3 arms: pembrolizumab monotherapy; pembrolizumab with platinum and 5-fluorouracil; or cetuximab with platinum and 5-fluorouracil (standard of care). Statistical analysis was stratified by PD-L1 expression defined by CPS. In the population with CPS ≥ 20, pembrolizumab monotherapy was associated with improved median OS as compared to cetuximab with chemotherapy (14.9 months vs. 10.7 months, HR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.45–0.83; p = 0.0007). Furthermore, pembrolizumab with chemotherapy improved OS vs. cetuximab with chemotherapy in the total population (13.0 months vs. 10.7 months, HR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.63–0.93; p = 0.0034), irrespective of CPS. The final analysis showed 2 populations that benefited from pembrolizumab therapy: those with CPS ≥ 20 (14.7 months vs. 11.0 months, HR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.45–0.82; p = 0.0004); and those with CPS ≥ 1 (13.6 months vs. 10.4 months, HR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.53–0.80; p < 0.0001). Despite these survival benefits, neither pembrolizumab alone nor pembrolizumab with chemotherapy improved PFS. Severe adverse events were reported in 55% of the pembrolizumab monotherapy arm, 85% of the pembrolizumab with chemotherapy arm, and 83% of the cetuximab with chemotherapy group.81 The KEYNOTE-048 trial led to change in the standard of care, and pembrolizumab in monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy are now accepted regimens in the therapy of PD-L1-positive (CPS ≥ 1) R/N SCCHN.53, 54

Nivolumab was approved for the second-line treatment of platinum-refractory R/N SCCHN based on the phase III CheckMate 141 trial.82 Ferris et al. enrolled 361 subjects who were randomized to receive either nivolumab or standard treatment (methotrexate, docetaxel or cetuximab). The nivolumab arm demonstrated higher median OS (7.5 months vs. 5.1 months) with a better safety profile (severe adverse events: 13.1% vs. 35.1%), irrespective of PD-L1 expression (<1% or ≥1%).82

Durvalumab therapy in a phase Ib/IIa study of immunotherapy-naive patients who had previously received platinum-containing regimens was well-tolerated83 and led to further clinical trials. For example, the phase II HAWK study focused on a population with high PD-L1 expression (≥25%) with platinum-refractory R/N SCCHN.84 Patients received durvalumab monotherapy for up to 12 months. The median PFS and OS were 2.1 months and 7.1 months, respectively. At the endpoint, the PFS and OS rates were 14.6% (95% CI: 8.5–22.1) and 33.6% (95% CI: 24.8–42.7), respectively. Severe adverse events were noted in 8.0% of patients. The authors concluded that durvalumab demonstrated anti-tumor activity with acceptable safety in PD-L1-high patients with R/N SCCHN, although further phase III trials are needed. The subsequent analysis showed higher ORR (29.4% vs. 10.9%) and longer OS (10.2 months vs. 5.0 months) with durvalumab in HPV-positive patients.84

The addition of tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4) to durvalumab therapy in the phase II CONDOR study85 and in the phase III randomized open-label EAGLE study86 did not demonstrate significant differences in ORR, OS, PFS, or DoR in patients with R/N SCCHN. Similarly, the CheckMate 651 trial compared ipilimumab plus nivolumab to cetuximab plus cisplatin/carboplatin plus fluorouracil (EXTREME regimen) followed by cetuximab maintenance in the first-line therapy of R/N SCCHN.87 This study was also negative, with no statistically significant differences in the median OS in the total population (13.9 months vs. 13.5 months, HR: 0.95; 97.9% CI: 0.80–1.13; p = 0.4951) or in the CPS ≥ 20 population (17.6 months vs. 14.6 months, HR: 0.78; 97.51% CI: 0.59–1.03; p = 0.0469). The PFS (5.4 months vs. 7.0 months) and ORR (34.1% vs. 36.0%) were also similar between the treatment arms.87

The combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab was further tested in CheckMate 714 for the treatment of R/N SCCHN.88 Participants were randomized 2:1 to receive nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab plus placebo for up to 2 years or until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or consent withdrawal. The ORR for platinum-refractory therapy in the doublet therapy arm was 13.2% (95% CI: 8.4–19.5) as compared to 18.3% in the monotherapy arm (95% CI: 10.6–28.4) (p = 0.290). The median DoR for nivolumab plus ipilimumab was not reached vs. 11.1 months for nivolumab alone. In patients with platinum-eligible disease, ORRs were 20.3% vs. 29.5%. The incidence of severe adverse events was similar – 15.8% for ipilimumab-nivolumab vs. 14.6% for nivolumab. The study did not meet its primary endpoint of demonstrating an ORR benefit with first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab therapy in platinum-refractory R/M SCCHN.88

Another ICI, avelumab, was evaluated in the JAVELIN Solid Tumor phase Ib trial in patients with platinum-refractory/ineligible R/M SCCHN, and demonstrated safety and modest clinical activity.89

The comparison of clinical trials focused on immunotherapy for metastatic or relapsed SCCHN is presented in Table 4.

Future perspectives

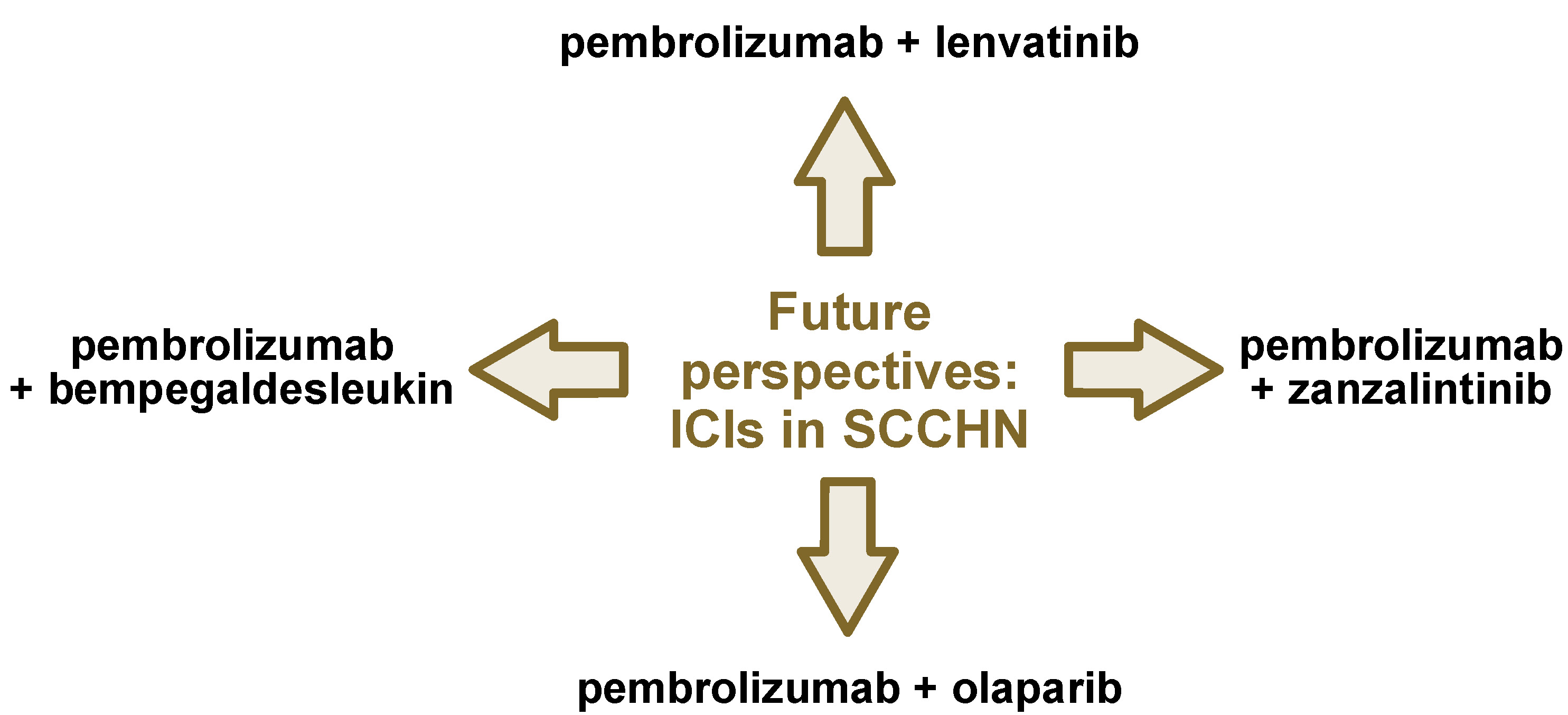

ICI therapy in head and neck cancer represents a promising frontier in improving patient outcomes. Recent advancement points to several emerging strategies that may enhance the efficacy of current approaches. The phase III LEAP-010 study evaluated pembrolizumab and lenvatinib (anti-LAG) for R/N SCCHN.90 Patients were randomized to receive either pembrolizumab 200 mg plus placebo (control) or pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib 20 mg daily (experimental group). Treatment continued for up to 35 cycles or until intolerable toxicity, progression or withdrawal. The median PFS (6.2 months vs. 2.8 months, p = 0.0001040) and ORR (46.1% vs. 25.4%, p = 0.0000251) were significantly improved in the experimental arm at the first interim analysis. However, the second interim analysis showed no significant difference in the median OS (15.0 months vs. 17.9 months, p = 0.882). The rate of severe adverse events was higher in the experimental arm (28% vs. 8%).90

The phase II LEAP-009 study demonstrated promising efficacy and safety for the lenvatinib and pembrolizumab combination in R/M SCCHN, which progressed after platinum and immunotherapy.91 Other potential enhancers of ICI therapy in the first-line R/M SCCHN treatment include the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib,92 the bifunctional EGFR/tumor growth factor beta (TGF-β) inhibitor BCA101,93 the multi-kinase inhibitor zanzalintinib,94 and recombinant IL-2 bempegaldesleukin.95 Collectively, these findings point to the next generation of clinical trials in SCCHN, focusing on combining targeted therapies with ICIs.

Improved patient outcomes may also result from the neoadjuvant applications of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). Recent studies suggest that applying ICB in the neoadjuvant setting could potentially promote systemic anti-tumor immunity, although further research is needed.96 Combination therapy with other immune-stimulating molecules often yields more successful outcomes than PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy in SCCHN. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 phase I, II and III trials revealed that combination therapy significantly improved ORR and 1-year OS in HPV-negative R/N SCCHN as compared to anti-PD-1 monotherapy; however, this benefit was not observed in HPV-positive cases.97

The indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 (IDO1) inhibitor epacadostat is still being investigated for potential PFS benefits when combined with pembrolizumab.98 Previously, epacadostat was evaluated in combination with PD-1 inhibitors in advanced solid tumors, demonstrating a tolerable safety profile and a relatively high ORR in the ECHO-304/KEYNOTE-669 study.99 Another IDO1 inhibitor, navoximod, was tested in combination with atezolizumab in a phase I trial for patients with solid tumors, showing a favorable safety profile, but inconclusive efficacy results.100

According to the SCORES study, the STAT3 inhibitor danvatirsen (AZD9150) demonstrated safety for use in combination with PD-1 inhibitors.101 The study also indicated potential anti-tumor activity of ICIs, with additional trials currently in progress.102, 103, 104 The most promising future directions are presented in Figure 1.

An inherent limitation of our review is the presence of ongoing clinical trials that may ultimately alter the paradigm of systemic therapy for head and neck cancer. Although several of these studies are discussed above, many currently report only partial or interim results.

Conclusions

Immunotherapy has been integrated into everyday clinical practice for metastatic or relapsed SCCHN, as confirmed by the ESMO and NCCN guidelines.53, 54 Other applications of ICIs in the management of SCCHN remain under development, with ongoing research focused on optimizing their efficacy and safety. In contrast, the inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway – most notably pembrolizumab and nivolumab – have demonstrated substantial clinical benefit in R/M SCCHN, and have therefore been incorporated into standard treatment algorithms. The role of CTLA-4 inhibitors, whether as monotherapy or in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, is less well established, but remains an active area of investigation.

The neoadjuvant and adjuvant use of ICIs has shown encouraging preliminary results in early-phase trials; however, larger randomized studies are required before these strategies can be adopted into routine clinical practice. Similarly, the combination of ICIs with definitive radiotherapy has produced mixed outcomes, with some trials demonstrating benefits, while others have failed to meet their primary endpoints.

Future directions in the field include the development of novel combination strategies incorporating targeted therapies, the identification of predictive biomarkers beyond PD-L1 expression, the design of immunotherapy approaches tailored to HPV-positive vs. HPV-negative disease, and the optimization of treatment sequencing and duration. As understanding of tumor immunology and the mechanisms underlying response and resistance to immunotherapy continues to advance, the therapeutic landscape for SCCHN is expected to further evolve, with the potential to improve outcomes in this challenging disease.105

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.