Abstract

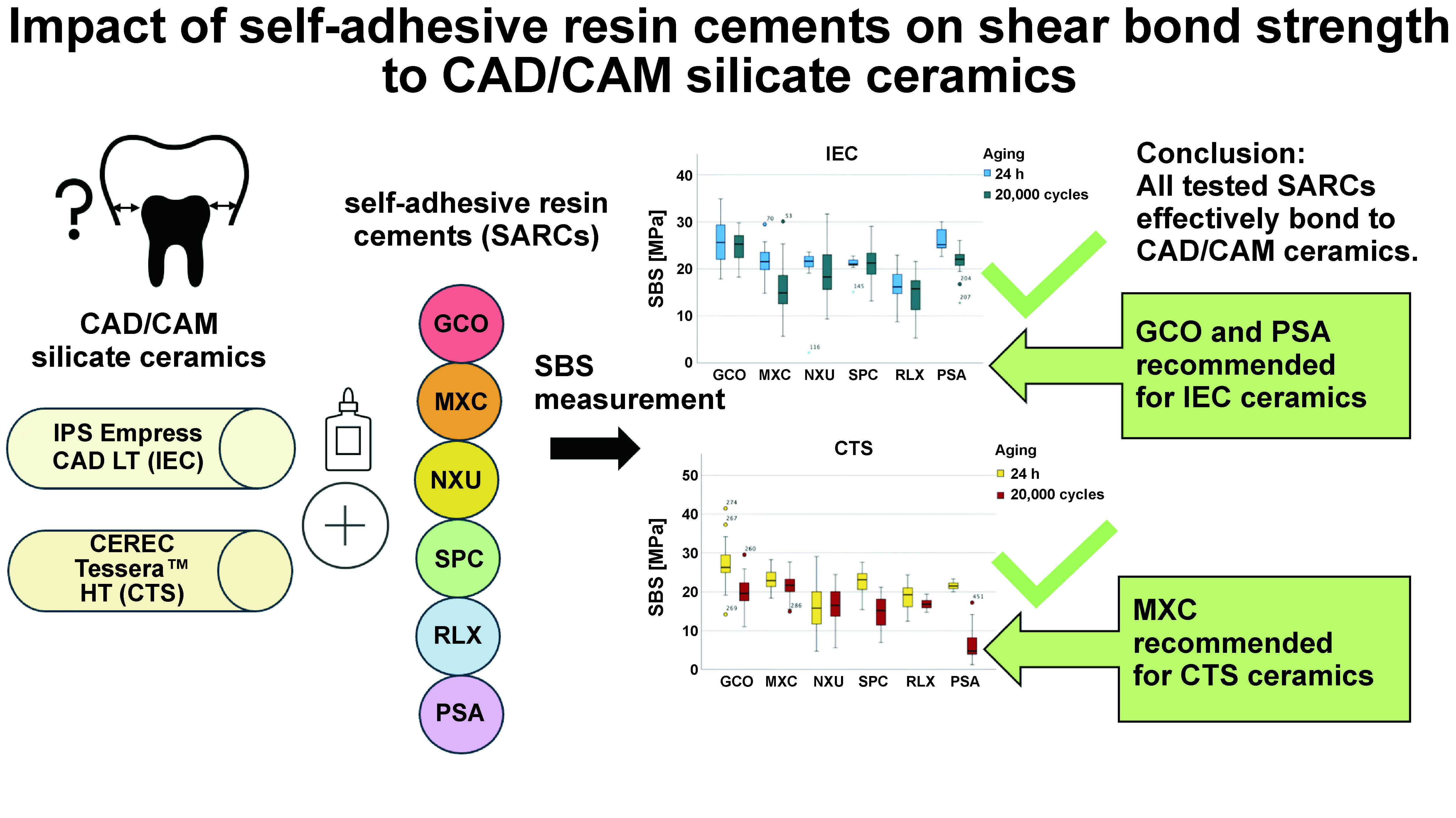

Background. The bond strength between self-adhesive resin cements (SARCs) and computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) ceramics is crucial for restoration durability, yet data on the aging effects of different SARCs remains limited.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to evaluate the shear bond strength (SBS) and failure modes of various SARCs on 2 CAD/CAM silicate ceramics after thermal aging.

Material and methods. A total of 360 samples from 2 ceramics (CEREC Tessera™ HT (CTS group); IPS Empress CAD LT (IEC group)) were treated with hydrofluoric acid (HF) and bonded with 6 SARCs: G-CEM ONE™ (GCO); Maxcem Elite™ (MXC); Nexus™ Universal (NXU); SpeedCEM® Plus (SPC); RelyX™ Universal (RLX); and PANAVIA™ SA Cement Universal (PSA). The samples underwent water storage (24 h, 37°C) or thermal aging (30 days, 20,000 cycles, 5–55°C). The shear bond strength and failure modes were measured, with the bonding interfaces being assessed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM). A multifactorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for the statistical analysis.

Results. Significant differences were identified in aging (F = 117.64, p < 0.001), ceramic types (F = 28.91, p < 0.001) and among SARCs (F = 34.79, p < 0.001). The highest SBS post-aging was found with IEC+GCO (24.92 ±2.90 MPa) and CTS+MXC (21.68 ±3.16 MPa), while the lowest SBS was recorded with CTS+PSA (6.22 ±4.31 MPa). Failure modes shifted from cohesive to mixed after thermocycling.

Conclusions. All tested SARCs bond effectively to CAD/CAM ceramics, with GCO and PSA being recommended for IEC ceramics, and MXC for CTS ceramics to optimize bond strength.

Keywords: CAD/CAM, resin cements, aging, bond strength, glass ceramics

Introduction

Modern computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technologies utilize highly advanced silicate ceramics, valued for their superior aesthetics and mechanical properties, which have led to their widespread adoption in restorations such as veneers, crowns, inlays, and onlays.1, 2 These ceramics incorporate crystals like feldspar, leucite, lithium disilicate, or zirconia, which, combined with heat and pressure, create homogeneity and reduce microcracks. The CAD/CAM processes further streamline restorations.3

Adhesive bonding is the preferred method for silicate ceramic restorations, often employing hydrofluoric acid (HF) etching4, 5 followed by silanization.6, 7 Hydrofluoric acid etching selectively dissolves the glassy phase of the ceramic, creating a micro-retentive surface that enhances micromechanical interlocking, while silanization promotes chemical bonding between the ceramic and resin-based adhesives. Alternative surface treatments, such as air particle abrasion with aluminum oxide particles (Al2O3), silica-coated aluminum oxide, diamond bur grinding and laser irradiation, can result in comparable bond strength when combined with an adhesive.8, 9 Akar et al. demonstrated that neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser irradiation (1–3 W) significantly enhanced the bond strength of self-adhesive resin cements (SARCs) to pre-sintered zirconia, while airborne particle abrasion may reduce it.10 The use of SARCs is increasing among general dentists and practitioners, as they simplify the process by eliminating the need for silane application and are often used in combination with universal adhesives.

The quality of adhesion depends on the bonded surface, surface treatment, ceramic material, adhesive and cement composition, and the amount of enamel or dentin present.4 Achieving stable restorations and reduced fracture risk is possible through physicochemical interactions at the interface between the tooth, resin cement and ceramic, enabling efficient stress transfer and enhancing restoration durability.11

Bonding agents range from multi-step composite cements to SARCs, which simplify clinical application by combining conventional and adhesive properties.12 With a low film thickness, high retention and mechanical strength, SARCs are ideal for non-metal-supported ceramics and offer a user-friendly, single-step application.13, 14, 15 Dual-curing SARCs can be self- or photo-activated, eliminating the need for separate pre-treatments or bonding agents.14 Their bond strength rivals that of traditional composite cements, though polymerization inefficiency in SARCs may impact adhesion durability.16

A recent study suggests that PANAVIA™ V5 achieves better results with certain ceramics, while SARCs demonstrate weaker outcomes.17 Despite extensive research on adhesive bonding in CAD/CAM restorations, current findings reveal considerable variability in bond strength outcomes, particularly for SARCs when applied to lithium disilicate ceramics.18 Additionally, thermocycling, a widely used aging protocol, has inconsistent effects on bonding durability across studies, complicating the interpretation of results and limiting clinical recommendations.19 These inconsistencies highlight critical knowledge gaps, especially regarding the performance of newly marketed SARCs and their interaction with different CAD/CAM ceramic systems.

While CAD/CAM restorations generally demonstrate favorable outcomes, they are prone to marginal decline over time due to composite wear and bond loss.5, 20 Debonding, especially with light-cured materials, often results from incomplete polymerization at the dentin interface.5 The use of dual-curing materials or adhesive layers can enhance bonding and reduce failure risk,21 although incomplete polymerization may release unreacted monomers, leading to hygroscopic swelling, cracks and restoration failure.22, 23

The effectiveness of SARCs and additional surface treatments remains the subject of debate.24 While some studies advocate for extra surface treatments to optimize bonding, others find SARCs effective as standalone solutions.12 However, inconsistencies in bonding performance, particularly under simulated intraoral aging conditions, highlight the need for systematic investigation. A significant challenge lies in the lack of standardized protocols for artificial aging, which contributes to variability and limits comparability in bonding studies.15 Inconsistencies in bonding data for self-adhesives and CAD/CAM ceramics, particularly lithium disilicate ceramics, underline the need for systematic investigation.

Self-adhesive resin cements offer clinical advantages, such as simplified application and bond strength comparable to multi-step systems, but their long-term performance remains insufficiently characterized. Addressing these gaps is essential to fully understand their interaction with different CAD/CAM ceramic systems and to provide robust clinical recommendations.

The aim of the present study is to test the latest SARCs and their interaction with CAD/CAM silicate ceramics under thermocycling, evaluating both their bond strength and long-term stability. Additionally, the study’s objective is to compare multiple novel SARCs with distinct monomer compositions, filler technologies and polymerization characteristics, focusing on shear bond strength (SBS) after water storage and thermocycling. By assessing their potential to improve adhesion without the need for separate silane pretreatment, we aim to provide clinically relevant insights into their durability and effectiveness. The null hypotheses tested were: (1) SARC type does not affect bond strength to CAD/CAM ceramics; (2) SARC type does not influence the failure mode.

Material and methods

Sample size estimation

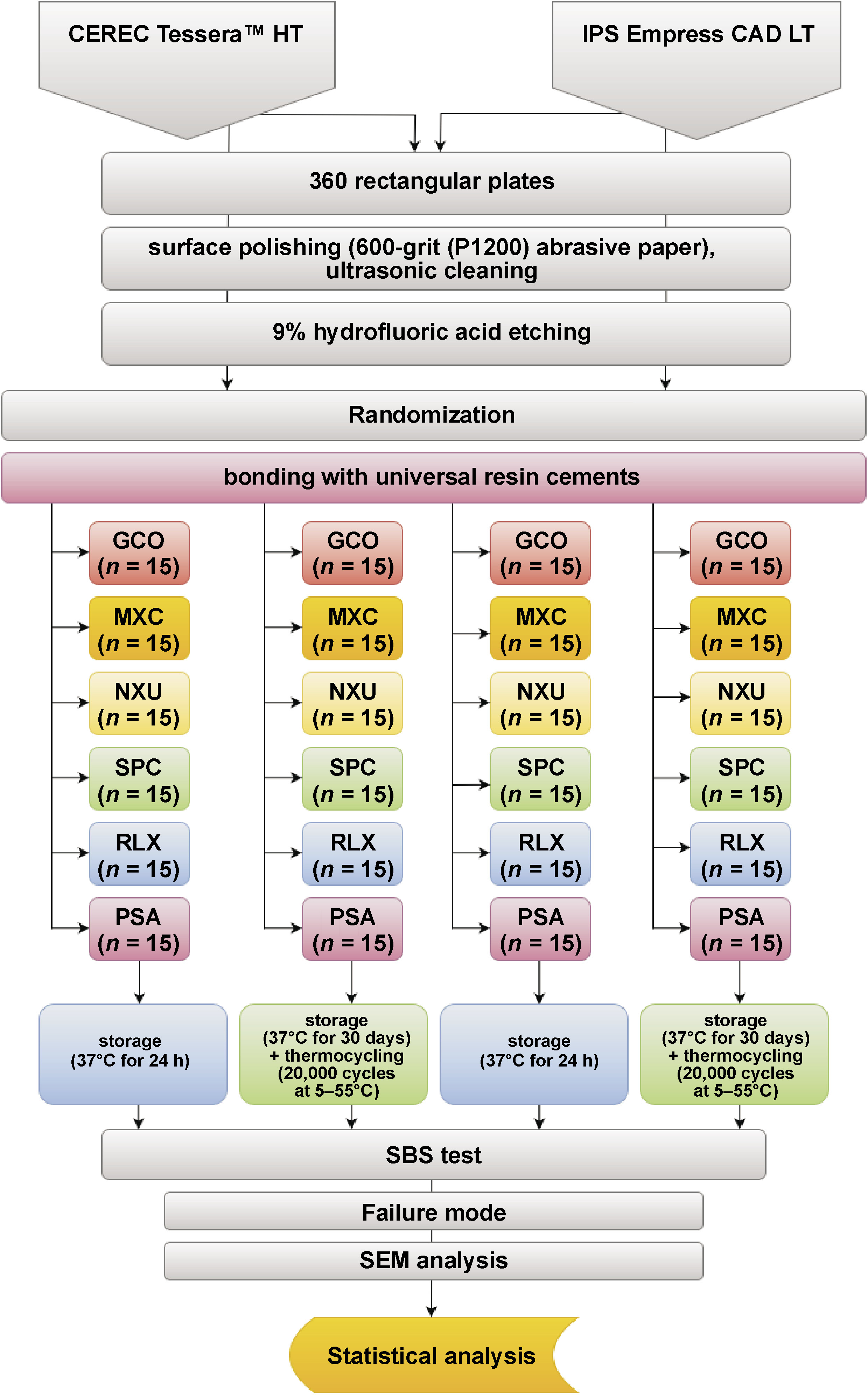

A priori sample size estimation was performed using G*Power v. 3.1 software (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany) to achieve a power of 80% (α = 0.05) for the multifactorial analysis of variance (ANOVA). The calculation of the total sample size was based on a medium effect size (f = 0.25) and 24 subgroups, with the resultant sample size of 270 specimens being distributed evenly across the subgroups. However, to enhance statistical power and ensure more robust results, a total of 360 specimens were ultimately used.

Preparation of study specimens

A total of 360 ceramic samples were prepared from CAD/CAM advanced lithium disilicate ceramic blocks (CEREC Tessera™ HT; Dentsply Sirona, Bensheim, Germany) (CTS) and CAD/CAM leucite-reinforced silicate ceramic blocks (IPS Empress CAD LT; Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) (IEC) according to the study protocol (Figure 1). The blocks were sectioned into 15-mm diameter discs with a thickness of 2.2 mm using a diamond saw under water cooling (Secotom-50; Struers, Ballerup, Denmark; and IsoMet® 1000; Buehler, Lake Bluff, USA). The dimensions of the samples were verified with a digital caliper (Alpha Professional Tools, Franklin, USA), and all surfaces were standardized through sequential grinding from P320 to P1200 silicon carbide sandpapers (SiC Foil; Struers). A total of 180 samples per ceramic type were produced and divided into 24 subgroups of 15 specimens each. Table 1 summarizes the materials used, including their brand names, manufacturers and chemical compositions. All ceramic samples were etched with 9% buffered HF (Ultradent™ Porcelain Etch; Ultradent Products, South Jordan, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommendations (CTS: 30 s; IEC: 60 s). Thereafter, the samples were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with distilled water for 8 min, and air-dried.

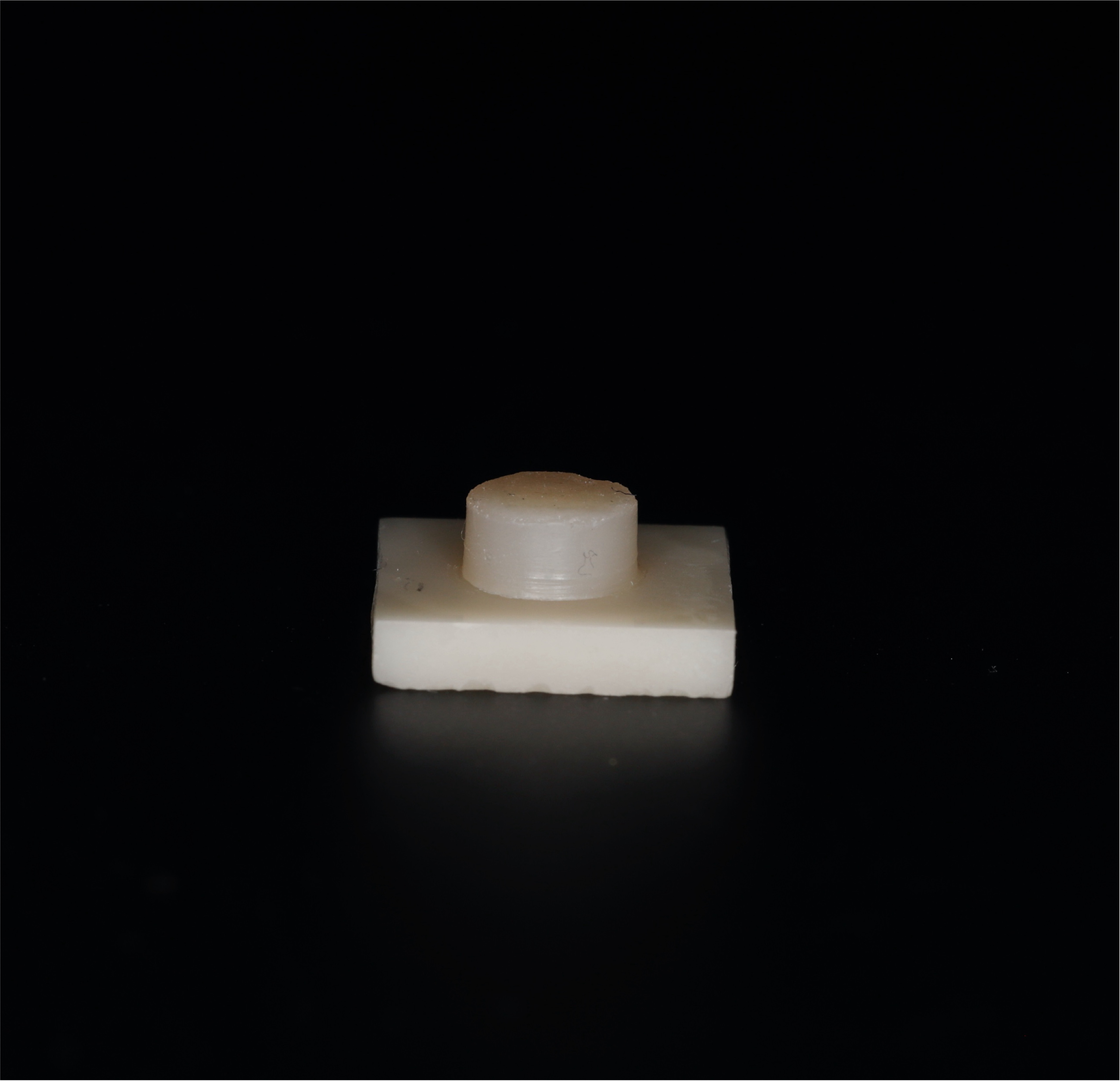

The samples were bonded with 6 SARCs: G-CEM ONE™ (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (GCO); Maxcem Elite™ (Kerr Corporation, Orange, USA) (MXC); Nexus™ Universal (Kerr Corporation) (NXU); SpeedCEM® Plus (Ivoclar Vivadent) (SPC); RelyX™ Universal (3M Deutschland GmbH, Neuss, Germany) (RLX); and PANAVIA™ SA Cement Universal (Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (PSA). The luting composite (SARC) was preheated in an incubator at 37°C for 1 min before application. Each ceramic specimen was positioned in a silicone mold to ensure a standardized bonding area. A Teflon mold (5 mm × 2 mm) was placed on the ceramic surface to define the shape of the composite cylinder, in accordance with ISO 10477.25 The composite material was applied in 2 increments of 1 mm each, with each layer being light-cured for 20 s using a light-emitting diode (LED) curing unit (Bluephase® Style; Ivoclar Vivadent) at 1,200 mW/cm2. After the removal of the Teflon mold, an additional 20-second light-curing step was performed to ensure complete polymerization (Figure 2). All procedures were performed by the same operator (MJ) to ensure consistency.

Aging protocol

Half of the specimens were stored in distilled water for 24 h at 37°C (non-aged group: NAG), while the other half underwent aging (aged group: AG) by storing in distilled water for 30 days at 37°C, followed by 20,000 thermocycles (5–55°C) with 30-second dwell time and 5-second transfer time (LAUDA RC 20 CS; Lauda, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany).

Evaluation of adhesion performance

After bonding, a 2-hour resting period was allowed. Then, the SBS measurements, expressed in megapascals (MPa), were performed using a universal testing device (zwickiLine Z0.5 TN; ZwickRoell, Ulm, Germany) at a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min. These metrics were calculated by dividing the breaking load, recorded in Newtons (N), by the bonding area, which was 19.63 mm2 for each sample. During the testing phase, the bonded surface was aligned with the force application mechanism. Shear forces were applied at the composite–ceramic interface using a knife-edge indenter, positioned to closely approximate the interface, ensuring precise measurement of bonding efficacy (Figure 3).

Assessment of fracture patterns

Fracture modes were analyzed under a stereomicroscope (VHX-5000; Keyence Corp., Osaka, Japan) at ×40 magnification. Two independent evaluators (CS, MJ) classified failures as adhesive (at the composite–ceramic interface), cohesive (within the ceramic) or mixed (combining both types).

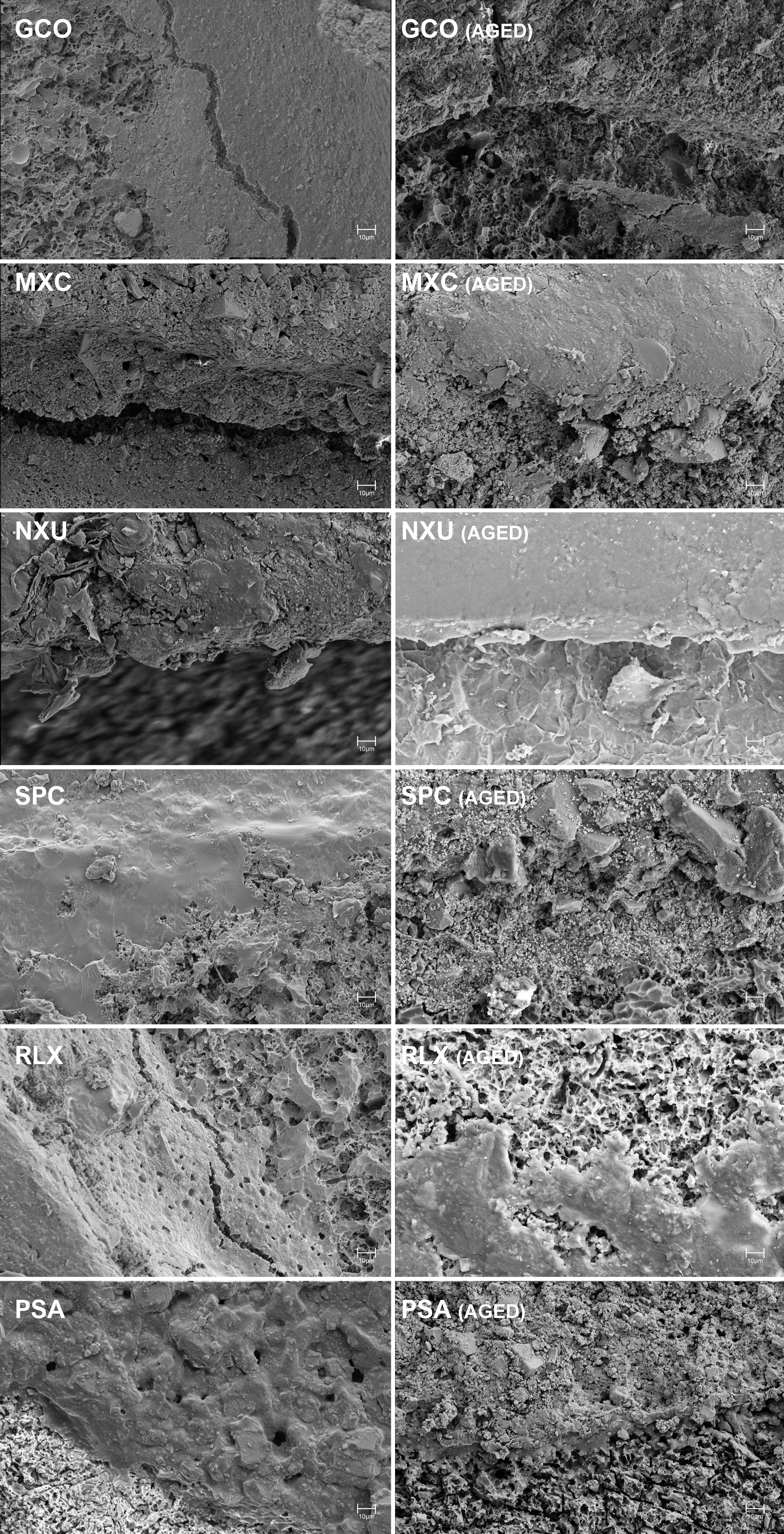

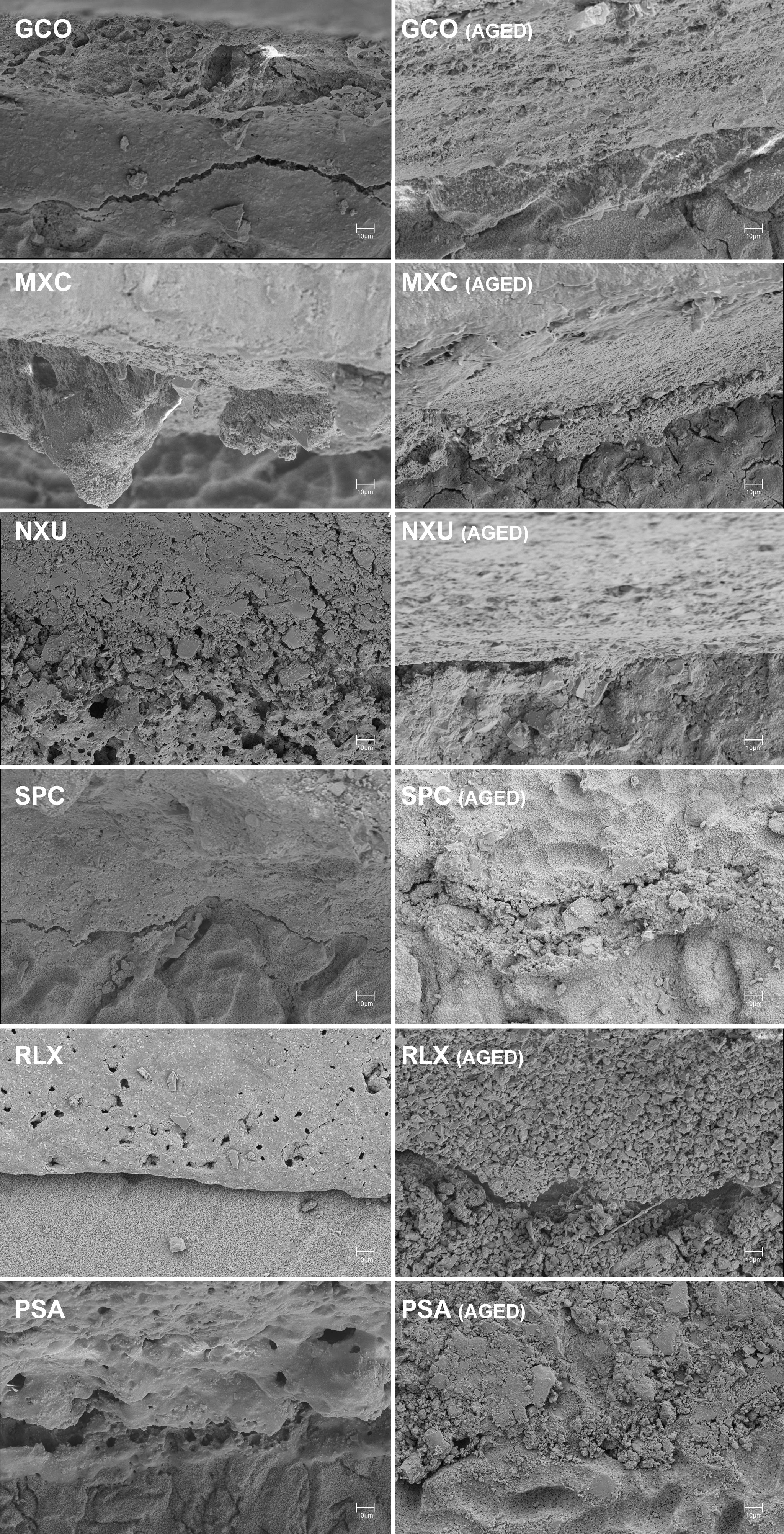

Analysis of adhesive interface using SEM

One specimen per group was randomly selected for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the adhesive interface. The samples were coated with a conductive gold-palladium layer (Q150T Plus; Quorum, Laughton, UK) and imaged at ×1,000 magnification (1,536 px × 1,024 px) using a scanning electron microscope (Sigma 360 VP; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The data was normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test), and homogeneity of variances was confirmed. A multifactorial ANOVA with Bonferroni correction was used to evaluate differences in bond strength among ceramics and cements, with the significance level set at α < 0.05.

Results

The assumptions for multifactorial analysis of variance were verified. The normal distribution of the data, assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the homogeneity of error variances, evaluated with the Levene’s test, were confirmed at both time points (p < 0.001). Aging induced by thermocycling led to a significant reduction in SBS values across all groups. There were notable differences between the pre- and post-thermocycling time points (F = 117.64, degrees of freedom (df) = 1, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.205). Additionally, significant differences were observed between the 2 ceramics examined (F = 28.91, df = 1, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.060), as well as among the universal cements (F = 34.79, df = 5, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.276). A significant interaction effect between the combination of ceramic type, universal cement and aging was also demonstrated (F = 10.99, df = 5, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.108).

Table 2 presents the SBS values for each group. The data indicated that the aged groups exhibited significantly lower values than those subjected to only 24 h of water storage. Prior to thermocycling, the highest SBS values were observed in the IEC group for PSA (26.02 ±2.28 MPa) and GCO (25.61 ±4.54 MPa), while in the CTS group, GCO (27.25 ±5.95 MPa) and MXC (23.26 ±2.50 MPa) were leading. After thermocycling, GCO was identified as the most robust material in the IEC group (24.92 ±2.90 MPa), followed by PSA (21.64 ±2.98 MPa). For CTS, MXC demonstrated the highest SBS values after aging (21.68 ±3.16 MPa). The lowest SBS after thermocycling was recorded for RLX in the IEC group (14.91 ±4.35 MPa) and for PSA in the CTS group (6.22 ±4.31 MPa). The significant differences between the various combinations of SARCs and ceramics, as well as pairwise comparisons for SBS values, are presented in Table 2.

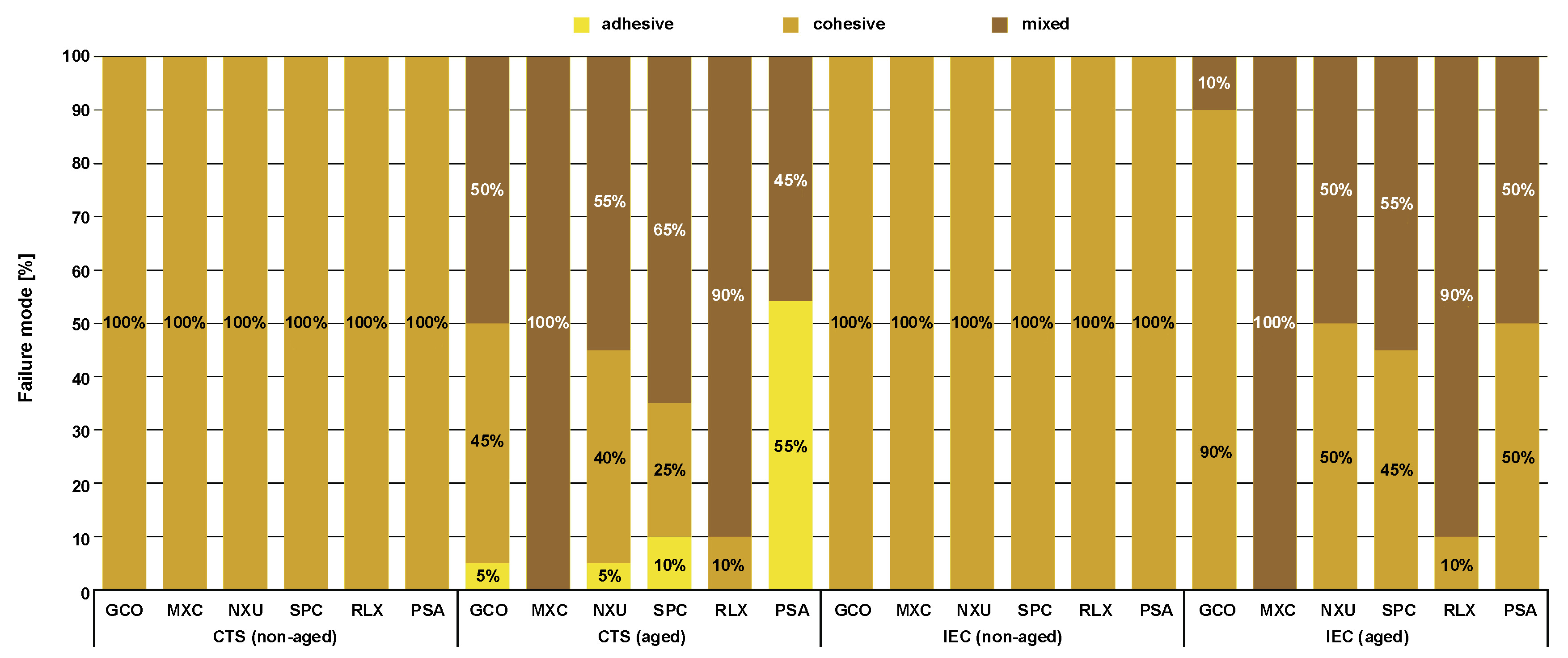

The failure mode analysis (Figure 4) showed that before thermocycling, the failures were cohesive, in both the IEC and CTS groups. After thermocycling, an increase in adhesive and mixed failure types was observed, with adhesive failures occurring sporadically. Representative SEM images of the bonding interfaces from each group (AG and NAG) are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6 at ×1,000 magnification. The images predominantly revealed continuous bonding zones. In the aged groups, more gaps and discontinuities were observed, with the resin showing fraying and the resin cement appearing looser. The bonding layers exhibited varying thicknesses and irregular structures, and the continuity of the adhesive layer was inconsistent. While top-down images suggested the presence of resin tags as surface features, their full extent and depth could not be assessed. Distinct differences in the microstructures of ceramics’ surfaces were revealed. The IEC group exhibited more porous and loosened structures after etching, with noticeable microporosities (Figure 5). The interface between the ceramic and the composite appeared poorly defined and displayed numerous cracks. In contrast, the CTS group presented smoother etched surfaces, with small cracks and irregularities dispersed throughout the material (Figure 6).

Discussion

The study aimed to investigate the impact of SARCs on the bond strength to 2 different CAD/CAM silicate ceramics (CTS and IEC) under various durability conditions. The results indicated that the bond strength remained consistent after thermocycling, with SBS values exhibiting only a slight decrease compared to 24-h water storage. However, the observed variations depended on the ceramic microstructure, particularly the differing compositions of the 2 tested glass ceramics, as well as on hydrolytic degradation and the specific composition of the resin cement. The novel SARCs used in this study are characterized by advanced monomer systems, such as 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (10-MDP) and 4-methacryloxyethyltrimellitic acid (4-MET), which improve bonding to ceramics without necessitating the separate application of silane. These innovations enhance polymerization efficiency, moisture resistance and bond durability. The unique features of these materials influence their adhesive performance, with further variations observed based on filler content, polymerization efficiency and hydrophilicity. However, prolonged water storage and thermal cycling caused a decrease in bond strength across all tested groups. Consequently, the null hypotheses were rejected, as it was demonstrated that SARC type significantly affected both SBS and failure modes.

Self-adhesive cements

The current study investigated a broad selection of SARCs to ensure representative coverage of various product categories. While some SARCs have been evaluated in other studies, these evaluations often occurred in isolation, limiting the direct comparability of results. The included SARCs were chosen based on their clinical relevance, market availability and unique formulation characteristics. This ensures a representative analysis of chemical compositions, polymerization mechanisms and their specific indications for CAD/CAM glass ceramics, as highlighted by manufacturers. The study aimed to provide evidence-based insights into the performance of currently marketed SARCs under standardized conditions, enabling more reliable comparisons and informed recommendations for clinical practice.

Bond strength

A major drawback of SARCs is their poor wettability, attributed to their high viscosity, which leads to limited infiltration.26 Compared to total-etch or self-etch systems, self-adhesive cements often exhibit lower bond strength, as they may not fully eliminate the smear layer.26, 27 This can result in a weaker hybrid layer between the cement and substrate, and negatively affect the adhesion between ceramics and SARCs.27 Furthermore, their bond strength depends not only on their viscosity and resulting wettability but also on the restorative material used. The results of this study are consistent with recent data demonstrating that SBS of cements is significantly influenced by the substrate.28 Therefore, it is crucial to carefully match the cement to the specific substrate. The chemical composition of SARCs, particularly the functional monomers they contain, may promote a particular affinity for certain ceramic core materials. The obtained bond values were similar to the recommended SBS of 15–20 MPa between the adhesive and dentin. In this study, IEC, which requires a longer etching time, demonstrated a significantly higher bond strength compared to CTS, thereby highlighting the impact of microstructural modifications through HF. Different microstructures of IEC and CTS can be attributed to their compositions (Table 1).29

In this study, the interaction between CTS ceramics and respective SARCs provided adequate adhesion, with all bond values initially exceeding the minimum threshold of 5 MPa (DIN EN ISO 10477).30 However, after aging, the bond strength of the CTS+PSA combination significantly decreased to 6.22 ±4.31 MPa, which was notably lower compared to other groups. Despite meeting the initial threshold, the significant reduction in bond strength for the CTS+PSA combination highlights that it is more susceptible to degradation over time. This decrease can be attributed to the composition of PSA cement, which contains bisphenol A diglycidyl methacrylate, triethylene glycol dimethacrylate and titanium dioxide. In combination with the CTS ceramics’ virgilite and phosphate content, these components likely resulted in suboptimal chemical interaction and compromised long-term adhesion. In contrast, IEC ceramics demonstrated superior performance, particularly in conjunction with GCO cement. The IEC+GCO combination achieved the highest bond strength after aging (24.92 ±2.90 MPa), which can be attributed to the interaction between GCO cement’s 10-MDP monomer and the silicon dioxide and aluminum oxide-rich reactive surface of the IEC ceramic. This reactive surface enhances adhesion, allowing IEC ceramics to consistently outperform CTS ceramics after aging. While CTS ceramics initially formed stronger bonds with certain cements, their lower reactivity compromised their long-term bonding potential. In addition, higher filler content in some cements could reduce bond strength by impeding the penetration of the adhesive resin.27

Thermocycling

The specimens were subjected to an aging process involving either 24-h or 30-day storage in deionized water at 37 ±1°C. This storage duration is described in DIN EN ISO 10477, and the duration of thermocycling varies between 0 and 20,000 cycles in comparable studies, with 20,000 cycles simulating approx. 2 years of clinical use.31, 32 Composites continuously absorb water in a moist environment, with water molecules diffusing through the plastic material as a permeable medium.33 This leads to hydrolysis at the interfaces between the composite and ceramic, as well as within the composite itself, which is a primary cause of bond weakening.34 In our study, thermocycling significantly reduced bond strength across all groups. The repeated thermal expansion and contraction likely induced mechanical stress at the composite–ceramic interface, contributing to debonding. Additionally, the absorption of water by the composites may have accelerated the process of hydrolysis, further compromising the integrity of the bond. The findings demonstrate that the combination of thermal fatigue and hydrolytic degradation plays a critical role in the long-term durability of ceramic bonding systems under conditions mimicking the oral environment.

Fracture modes

The observed bond weakening had an influence on the fracture patterns. The IEC and CTS groups primarily exhibited cohesive failures before thermocycling, with an increase in mixed failures afterward. The CTS+PSA group displayed a significant number of adhesive fractures and the lowest bond strength. In the remaining groups, adhesive fractures occurred in around 5–10% of cases, with mixed and cohesive failures being more prevalent. These fracture patterns likely result from the uneven distribution of lithium disilicate (IEC) and virgilite crystals (CTS) combined with hydrolytic degradation. The presence of mixed failures indicates a combination of strong and weak adhesion, resulting from material heterogeneity. Thermocycling reduced bond strength across all SARCs, a finding that is consistent with the results of previous studies.8, 9

SEM

The SEM analysis in the present study underscores the impact of aging on the adhesive interface between ceramics and SARCs. After thermocycling, the presence of gaps and resin fraying indicated compromised adhesive integrity, aligning with reduced bond strength values. The more porous, loosened structure of IEC after etching facilitated enhanced micromechanical interlocking, which correlated with higher pre-aging bond strength. However, after thermocycling, an increase in mixed failures was observed. This suggests that while the porous nature of IEC might enhance initial bonding, it may also contribute to mechanical stress and crack formation over time, leading to complex failure patterns rather than purely adhesive failures.

Despite these observations, the images indicated strong micromechanical interlocking at the composite–ceramic interface, highlighting generally robust bonding. However, the presence of gaps and structural irregularities in the aged specimens suggests potential vulnerabilities.

In contrast, CTS exhibited a smoother etched surface with fewer cracks and irregularities, which likely contributed to a weaker adhesive interface. The lower degree of porosity observed in CTS might explain the generally lower bond strength exhibited by this ceramic, as less mechanical interlocking occurred. This reduced interlocking potential may have contributed to the higher percentage of adhesive failures observed in the CTS+PSA group after aging, where the weakest bond strength was recorded.

Limitations

The SEM findings indicate potential weaknesses in the adhesive interface after thermocycling, though these observations must be interpreted within the limitations of this in vitro study. A key limitation is the inability to fully replicate intraoral conditions. Factors like temperature fluctuations, saliva and masticatory stresses are only partially simulated, limiting the direct clinical applicability of the results. Additionally, long-term effects, particularly material aging, were not fully captured within the study’s timeframe. The study focused solely on the ceramic–cement bond, excluding dental hard tissue, which is essential for clinical adhesion. It is important to note that the results are limited to the adhesion between the tested ceramics and SARCs, and do not provide data on adhesion to enamel or dentin. While in vitro studies predominate due to the challenges of in vivo testing, comparing results across studies requires caution, as variations in protocols and testing conditions, along with the lack of a uniform protocol for artificial aging, complicate the comparability of study outcomes. Thus, the findings of this study are restricted to the specific ceramics tested (leucite-reinforced and lithium disilicate ceramics) and cannot be generalized to other ceramic types or clinical scenarios involving enamel or dentin. It is recommended that future research include long-term clinical evaluations, with particular emphasis on material aging and bond durability under real oral conditions.

Conclusions

All tested SARCs are suitable for bonding CAD/CAM silicate ceramics in clinical practice. However, to achieve optimal bond strength, specific recommendations should be followed based on the type of ceramic. GCO and PSA cements are the most effective for bonding leucite-reinforced silicate ceramics (IEC), providing the highest bond strength and durability. For CAD/CAM advanced lithium disilicate ceramics (CTS), MXC cement is recommended, as it demonstrated superior performance compared with the other cements. However, the process of aging and the storage weaken the adhesive bond, particularly after thermocycling, which compromises long-term durability. These findings, however, are limited to adhesive performance on the 2 tested ceramics and cannot be extrapolated to clinical conditions involving enamel or dentin adhesion.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.