Abstract

Background. The conventional method of removing caries lesions is an anxiety-inducing process that often necessitates the administration of local anesthesia and the extensive removal of tooth structure. Therefore, minimally invasive procedures are required to preserve tooth structure and minimize discomfort.

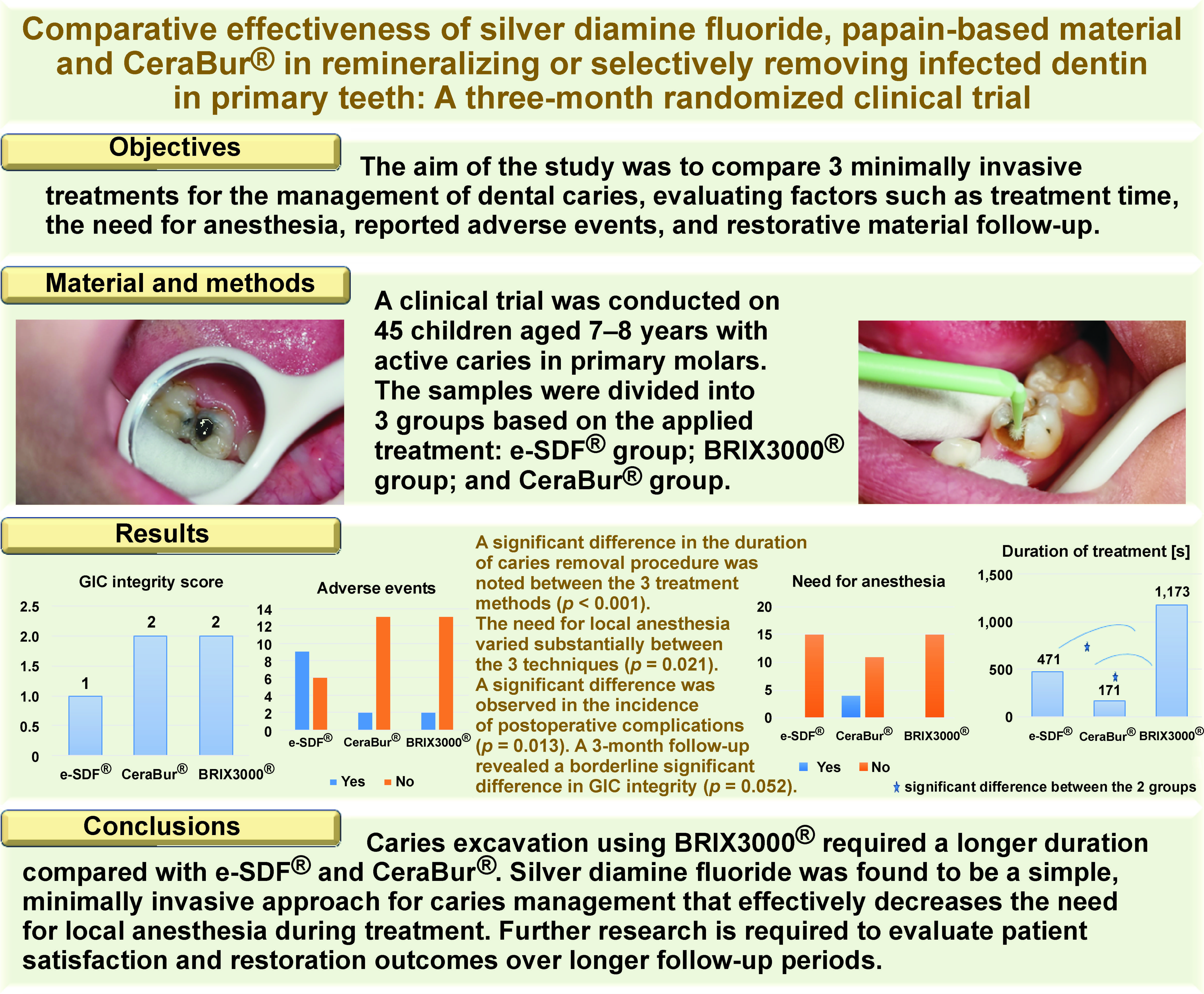

Objectives. The aim of the study was to compare 3 minimally invasive treatments for the management of dental caries, evaluating factors such as treatment time, the need for anesthesia, reported adverse events, and restorative material follow-up.

Material and methods. A clinical trial was conducted on 45 children aged 7–8 years with active caries in primary molars. The samples were divided into 3 groups based on the applied treatment: 38% silver diamine fluoride (e-SDF®) group; BRIX3000® group; and CeraBur® group. The duration of treatment was recorded using a stopwatch. Adverse events, including tooth pain irritations, lesions, spots, and discolorations, were reported by parents within 2 weeks. The durability of the restorative material, namely glass ionomer cement (GIC), was assessed after 3 months. The χ2 and Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to analyze the data. The values were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

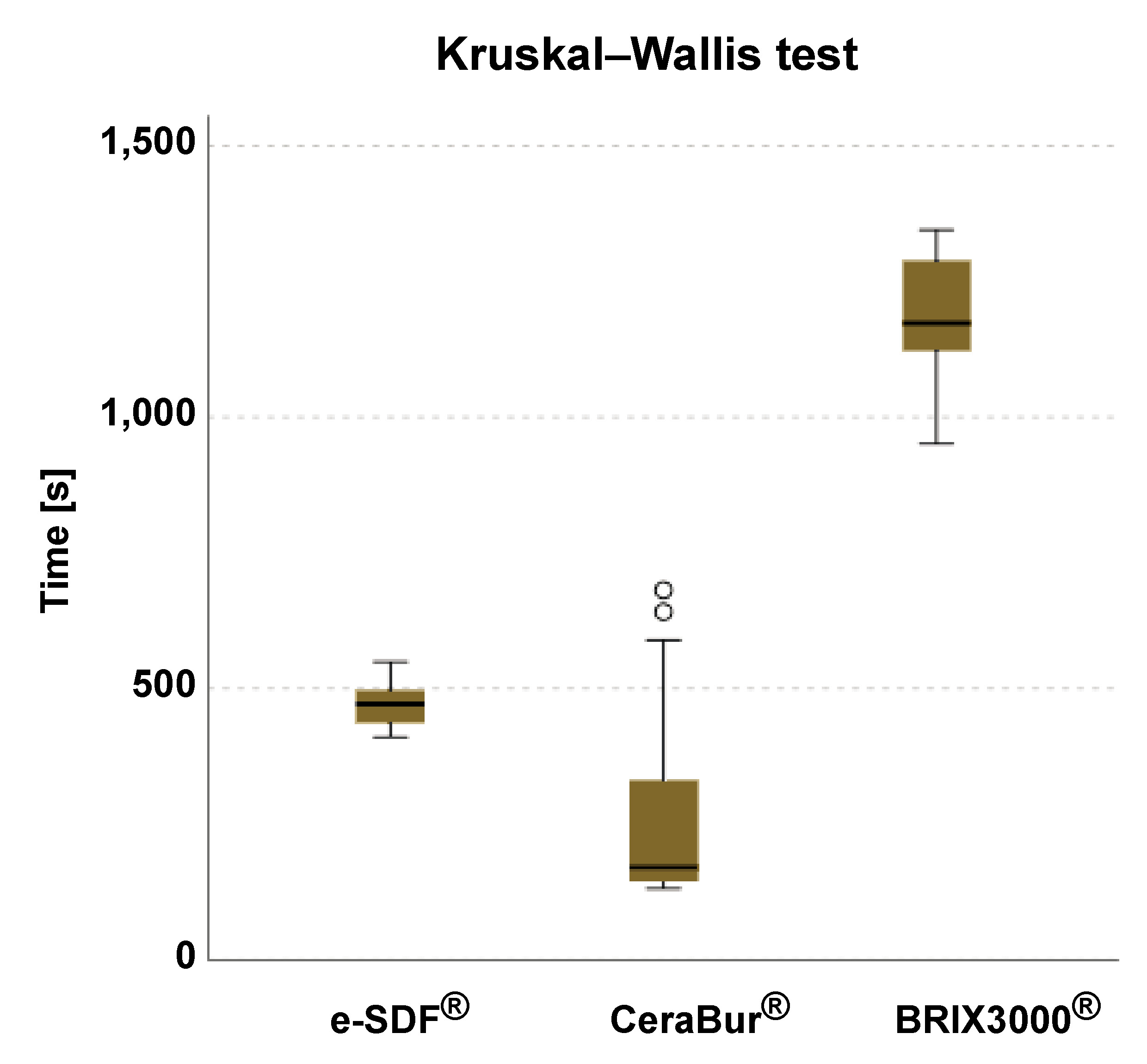

Results. A significant difference in the duration of caries removal procedure was noted between the 3 treatment methods based on the median values (e-SDF®: 471 s, CeraBur®: 171 s, BRIX3000®: 1,173 s) (p < 0.001). Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated significant differences in duration of the procedure between the CeraBur® and BRIX3000® groups, as well as between the e-SDF® and BRIX3000® groups (p < 0.001). The need for local anesthesia varied significantly between the 3 methods (p = 0.021). A significant difference was observed in the incidence of postoperative complications among the 3 methods, with the rate of adverse events equaling 9 (60.0%) in the e-SDF® group and 2 (13.3%) in the remaining groups (p = 0.013). A 3-month follow-up revealed a borderline significant difference in GIC integrity among the 3 methods (p = 0.052).

Conclusions. Caries excavation using BRIX3000® required a longer duration compared with e-SDF® and CeraBur®. Silver diamine fluoride was found to be a simple, minimally invasive approach for caries management and was effective in reducing the need for local anesthesia during treatment. Further research is required to evaluate patient satisfaction and restoration outcomes over longer follow-up periods.

Keywords: silver diamine fluoride, ceramic bur, chemomechanical caries removal, minimally invasive dentistry, BRIX3000

Introduction

Dental caries is a common condition that affects individuals on a global scale.1 It occurs over an extended period and results from 3 factors, namely acid-producing bacteria, fermentable carbohydrates and host components, such as teeth and saliva.2 Despite a decrease in the occurrence of caries in many industrialized nations as compared to previous decades, it remains an important public health problem.3

The conventional method of caries removal using the dental burs is the most prevalent procedure in dental treatment. Nevertheless, this technique is consistently linked to numerous drawbacks, including patients perceiving drilling as an unpleasant sensation, the frequent need for local anesthesia, the potential for drilling to cause harmful thermal effects on the pulp, and the possibility of excessive removal of the healthy tooth structure.4

The necessity for minimal intervention and painless dentistry, which provide relief and solace while fostering a positive attitude toward dental procedures, is one of the justifications for the field of pediatric dentistry.5

The objective of minimally invasive procedures is to preserve as much tooth structure as possible, to ensure that teeth remain functional for longer periods, and, in the case of deciduous teeth, to promote their retention until natural exfoliation. These methods have been shown to be both cost-effective and acceptable to parents and pediatric patients, while causing the least possible pain and discomfort to the child.6

Various strategies have been developed for the management of caries without the use of rotary devices, including mechanical atraumatic restorative treatment (ART), fluoride-based caries arrest, and other minimally invasive treatments such as chemomechanical caries removal (CMCR).7

For the elimination of carious dentin, a novel slow-speed rotary ceramic bur (CeraBur®) was constructed from zirconia stabilized with alumina–yttria. This instrument effectively eliminates caries from infected soft dentin and reduces the need for the spoon excavator.8 Ceramic burs are advantageous for the excavation of dentin caries due to their superior cutting efficacy. Additionally, they possess an exceptionally efficient capacity for excavating delicate carious dentin while minimizing damage to the hard structure of the tooth. As a result, ceramic burs ought to be appropriate for minimally invasive caries excavation, as they result in a reduced number of dentinal tubules, thereby eliciting fewer pain sensations.9

According to Abdellatif et al., although fluoride varnish has shown efficacy in reducing caries, it lacks the capacity to cure deep carious lesions.10 The efficacy of silver diamine fluoride (SDF) in halting caries progression in enamel lesions has been acknowledged.11

Silver diamine fluoride is considered a simple and cost-effective technique that does not require patient participation or complex training from healthcare providers. In resource-constrained regions, this approach may be very beneficial as a substitute for costly preventative interventions.12

The combined effects of fluoride’s ability to facilitate remineralization and silver’s antibacterial and collagenase inhibitor properties are synergistically used to impede the advancement of dental caries lesions and mitigate the occurrence of dental caries.13

The use of minimally invasive procedures has shown a noticeable rise, particularly in the context of pediatric patients. Chemomechanical caries removal is a minimally invasive approach that effectively disintegrates decaying tissue while conserving the integrity of the tooth structure and minimizing potential pulp irritation and patient distress. The method entails the removal of deteriorated tissue by using natural or synthetic substances to dissolve and facilitate the elimination of the diseased tissue.7 The procedure requires the use of chemical agents to soften the carious dentin, which is then eliminated by a meticulous excavation process.14 Chemomechanical agents for caries elimination have been utilized since 1975. Examples of such compositions include sodium hypochlorite,15 GK-10116 and Carisolv (Medi Team, Sävedalen, Sweden).17

The papain gel (Papacárie; Fórmula & Ação, São Paulo, Brazil) was developed as a result of a research initiative conducted in Brazil in 2003. The Carie-Care™ (UnibioTech Pharmaceuticals Pvt Ltd., Chennai, India), a gel produced from Carica papaya containing a purified enzyme, was created in India. This gel incorporates the antibacterial and analgesic properties of clove oil.18

BRIX3000® (Brix Medical Science), a chemomechanical agent, was introduced in 2012. It is a papain-based preparation, containing a proteolytic enzyme derived from the latex and fruits of green papaya (C. papaya). This enzyme functions as a chemical degradant. According to the producers, the distinguishing factor of this product is the quantity of papain used, specifically 3,000 U/mg at a concentration of 10%.19

Both SDF and BRIX3000® therapies are minimally invasive and effective in the management of early caries. However, a comparison of their working time, follow-up acceptance and overlying restoration durability remains to be conducted. The paucity of robust comparative studies has resulted in a limited clinical guidance on the optimal or most practical treatment of different patient populations, particularly with regard to safety, patient compliance and cost-effectiveness.

The present study was conducted to compare 3 minimally invasive treatments with regard to treatment time (efficiency), the need for anesthesia, reported adverse events, and restorative material (glass ionomer cement (GIC)) follow-up.

The null hypothesis stated that there was no discernible difference in terms of treatment time, reported adverse events and restoration integrity among the 3 substances: SDF (e-SDF®); a papain-based CMCR product (BRIX3000®); and a ceramic bur (CeraBur®).

Material and methods

A randomized clinical trial was conducted on a sample of schoolchildren who were visiting the postgraduate clinic at the Department of Orthodontics, Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Mustansiriyah University (Baghdad, Iraq). The trial was conducted following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist. The process of collecting data commenced in early December 2023 and continued until April 2024.

Study sample

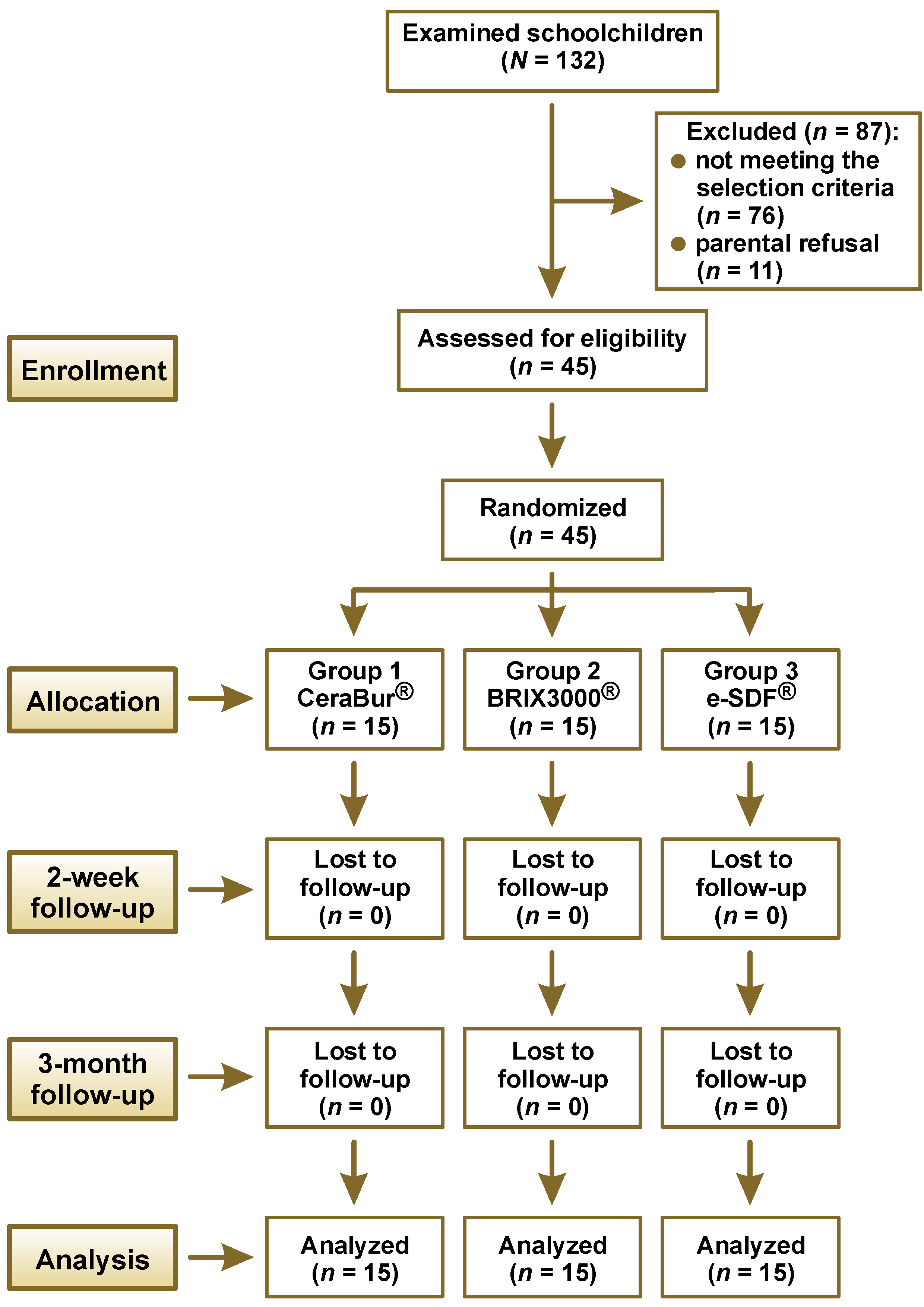

The study population comprised 45 children, selected from a total of 132 children attending second stage of primary school. Eighty-seven subjects were excluded due to either non-compliance with the established criteria or due to their parents’ refusal (Figure 1). The sample size was determined according to the previous studies20, 21 regarding GIC durability, secondary caries and pathological change after 3 months of recall. The sample size was double-checked using G*Power v. 3.1.9.4 software (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). With the effect size (f) of 0.5, the α error probability of 0.05, the power (1−β error probability) of 0.80, and the actual power of 0.8034136, the sample size was determined to be 42. The size of the study group was increased to 45 participants in order to account for possible dropouts.

A total of 45 participants were randomly divided into 3 groups of 15 participants each (allocation ratio of 1:1:1), as follows: e-SDF® group; BRIX3000® group; and CeraBur® group. The randomization code was generated using Research Randomizer software (https://www.randomizer.org). A block size of 3 was used to ensure equal numbers of patients in all 3 groups. The allocation of patients to treatment groups was concealed using sealed envelope techniques.

The study participants were aged between 7 and 8 years and had active caries lesions on their primary molars (International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) II code 5). The subjects were selected based on particular criteria.

Selection criteria

Children were included in the current investigation provided they met the following criteria, as reported by multiple studies,22, 23, 24 with some modifications:

1. The children had no documented history of oral or systemic disorders, and were in good physical condition.

2. Each child presented with primary molars with open carious lesions, either on the occlusal surface or the proximal surface, in the absence of a neighboring tooth (slot cavity). These lesions affected the dentin but did not expose the pulp. The depth of the cavities was measured using a DIAGNOdent caries detector, with a range of 40–99, in accordance with the ICDAS II code 5, which does not involve the pulp.25

3. The cavities were easily reachable by hand tools and were of a size sufficient to allow the entry of a small excavator.

4. There was no clinical evidence of pulp or periapical infections in the vital primary molars, and the patient was not exhibiting any symptoms.

5. The teeth with a normal cusp and fossa, free from attrition, destruction or enamel defects that affect the retention of GIC restoration were chosen.

6. The child’s behavior was deemed as accurate when assessed using Wright’s clinical classification26 as “cooperative”, excluding both “lacking in cooperative ability” and “potentially cooperative” categories.

Study groups

The study sample was divided into 3 groups, as follows:

– e-SDF® group: treated with 38% SDF (e-SDF®; Kids-e-dental LLP, Mumbai, India);

– BRIX3000® group: treated with a papain-based gel (BRIX3000®; OralMed Global LTD, Carcarañá, Argentina);

– CeraBur® group: control group treated with a slow-speed handpiece with a ceramic bur (CeraBur® K1SM; Komet, Lemgo, Germany).

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups and received a specific treatment technique for a designated tooth.

Oral examination method

The oral examination was conducted after the child was positioned in the dentist’s chair, with the operation light providing assistance. In order to maintain the consistency and validity of the study, the study procedure was accomplished using appropriate equipment by a single operator with 5 years of experience in the field, who had undergone dedicated training. The identification of dental caries was performed using visual and tactile perceptions, with the aid of a dental mirror and a probe. Before the initiation of the caries removal procedure, the depth of carious lesions was evaluated using the ICDAS II and the DIAGNOdent caries detector that was calibrated before each patient. The research process continued when the subject met all the specified requirements.

Clinical procedure

The clinical procedure was conducted according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and instruction catalogue for each material used.21, 27, 28, 29

All teeth were isolated using a cotton roll and a saliva ejector. The occlusal surface was brushed to remove any accumulated debris and plaque. Before the commencement of caries removal treatment, the depth of carious lesions was evaluated using the DIAGNOdent caries detector, and the findings were documented in the patient’s case sheet. The measurement of time was initiated with the use of a stopwatch.

In the BRIX3000® group, the manufacturer’s guidelines were followed; BRIX3000® was applied to the cavity using a microbrush and left in place for approx. 2–3 min. Subsequently, the infected dentin that had dissolved was removed with a spoon excavator, without applying pressure or making incisions. In instances where the cavity was still occupied with infected dentin, the implementation of an additional layer of the agent might have been necessary (Figure 2). When sound dentin of the cavity was reached and all infected dentin was removed (Figure 3), the stopwatch was halted and the duration of the procedure was recorded in the case sheet, signifying the completion of the caries removal process.

In the e-SDF® group, patients’ faces and gums were protected with a petroleum gel (Vaseline®) to avoid staining. The application of 38% SDF was performed twice with a microbrush on the affected tooth surface, and surplus material was removed using cotton pellets (Figure 4). In accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, the time required for the material to act is 2 min per single application. The black discoloration manifested subsequent to double application of the agent (Figure 5), after which the stopwatch was halted and the duration of the procedure was recorded in the case sheet, signifying the conclusion of caries treatment.

In the CeraBur® group, caries removal was performed using a low-speed handpiece with a ceramic bur (CeraBur® K1SM; Komet). In the absence of a water coolant, the removal of carious tissue was conducted through the use of circular motions, from the center of the cavity to its boundary. Following the identification of hard dentin, the process of caries excavation was stopped, the stopwatch was halted, and the duration of the procedure was recorded in the case sheet, thus signifying the completion of the caries removal process.

The tooth surface in all 3 treatment groups was conditioned with polyacrylic acid to remove the smear layer. Subsequently, it was washed and dried using dry pellets.

The glass ionomer restoration (Riva Self Cure; SDI Inc., Bayswater, Australia) was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mixed glass ionomer was placed into the cavity, with the applier’s flat end being utilized to ensure the material was introduced into the corners of the cavity, resulting in slight overfilling. The bite was checked and any excess material was manually extracted, if necessary. The patient was instructed to refrain from eating for at least 1 h.

Time assessment

The duration of therapy for each group was measured using a digital stopwatch. The stopwatch for all study groups was started as soon as the depth assessment was recorded by the DIAGNOdent.

In the CeraBur® and BRIX3000® groups, the time was stopped as the cavity was found to be caries-free. In the e-SDF® group, the time for the black discoloration to manifest after double application of e-SDF® was 2 min, as determined by the manufacturer’s instructions.

In cases where local anesthesia was necessary, the stated time for caries removal included the time allocated for the administration of the anesthetic agent.

Adverse events

The incidence of potential adverse events in 3 groups reported by the patients within 2 weeks was the primary outcome of the study. Complications include tooth pain or sensitivity, poor taste, tooth discoloration, and potential irritations, lesions, or spots on the mucosa, gingiva and skin.

Restoration follow-up

Recall and follow-up examinations were performed at 3 months and regarded as a secondary outcome of the study. The assessment ratings were adapted from the study by Satyarup et al.28 and scored as follows: score 1 – restoration is fully intact, covering all pits and fissures; score 2 – restoration is partially lost, but the tooth itself is in good condition with no active or soft caries; score 3 – restoration is partially lost and the tooth has active or soft caries; score 4 – restoration is completely lost, but the tooth itself is sound; score 5 – restoration is completely lost and the tooth has caries. A tooth was deemed sound if its surface exhibited a firm and lustrous texture.28

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The χ2 test was utilized to compare the percentages of nominal variables between two or more independent groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to test hypotheses concerning medians of quantitative and ordinal variables between more than 2 independent groups. Values were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

The sample distribution according to age, sex, type of teeth treated, and cavity location is illustrated in Table 1 and Table 2.

Duration of caries removal procedure

As demonstrated in Table 3, a significant difference in the duration of caries removal was observed among the 3 treatment methods (p < 0.001). Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated significant differences between the CeraBur® and BRIX3000® groups (p < 0.001), as well as between the e-SDF® and BRIX3000® groups (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Need for anesthesia

Table 5 shows a significant difference in the requirement for anesthesia among the 3 caries treatment methods (p = 0.021). Specifically, 4 out of 15 children treated with the CeraBur® method required dental anesthesia during the caries removal procedure. In contrast, none of the children treated with e-SDF® or BRIX3000® required anesthesia.

Postoperative adverse events

The study outcomes revealed a significant difference in postoperative adverse events among the 3 treatment methods (p = 0.013). Specifically, 9 out of 15 children treated with the SDF method reported a discoloration following the clinical procedure of caries removal, compared to only 2 of the children treated with the CeraBur® or BRIX3000® methods who showed dental sensitivity or pain (Table 6).

GIC filling after 3 months

As illustrated in Table 7, a non-significant difference in GIC filling integrity is evident among the 3 caries treatment methods following 3 months of follow-up (p = 0.052).

Discussion

Conventional caries removal methods involve drilling with a high-speed handpiece to access the carious lesions and a low-speed handpiece to remove the carious tissue. Although fast and efficient caries removal can be achieved using these techniques, drilling stimulates discomfort and pain. Therefore, local anesthesia is routinely needed.22 The employment of minimally invasive techniques can address and overcome other issues, such as overheating the pulp, vibration and noise.

In the present study, the examination of dental caries was performed for each tooth to determine the depth of the carious lesion. The DIAGNOdent caries detection instrument was used in numerous studies as a non-invasive method of assessing the extent of lesions.30, 31 While its sensitivity and specificity have been accepted, it should be used in combination with a visual method to minimize false positive errors.32 Thus, in the present study, the ICDAS II code 5, which does not involve the pulp for occlusal and proximal lesions, was used in addition to the DIAGNOdent to evaluate lesion depth.25

In pediatric dentistry, it is important to reduce procedure time, ensure pain-free intervention, and opt for restorations that are less technique-sensitive to manage the child’s behavior. In the course of the present study, the use of SDF did not elicit a pain reaction, as this method does not necessitate the application of pressure to caries lesions. Furthermore, the CMCR technique requires minimum pressure to remove softened caries tissue from the tooth cavity. As a result, both of these groups had a significantly lower demand for anesthesia in comparison to the CeraBur® group.

Although a ceramic bur removes infected dentin only, it produces mild vibrations during the process of cavity preparation. Dental anesthesia was applied according to the patient’s pain threshold and to control the child’s behavior. This result was consistent with the studies by Nagaveni et al.5 and Ismail and Haidar,22 with the latter concluding that BRIX3000® removes infected dentin only, thus eliminating the painful removal of sound dentin or the need for local anesthesia.

In pediatric patients, it is important to balance between the duration of the procedure and the efficient management of behavior.33 Previous studies have suggested a relationship between behavior during treatment and treatment duration in children.34 Consequently, when developing a therapy plan for pediatric patients, chair time is a crucial consideration, as longer treatments can trigger negative behaviors in children. Furthermore, it is well recognized that shorter treatment durations result in lower expenses and an increased number of patients receiving benefits, particularly in the field of public health.35 The time of the procedure in the dental clinic depends on multiple factors, including child behavior, procedure acceptance, controlling tooth isolation, the presence of debris on the available carious cavity, the time required for cavity preparation, and the dentist’s experience. In the current study, the time was measured in each group excluding any sudden intervals in the procedure that were out of procedural focus. Regarding treatment efficiency, the BRIX3000® group required the longest treatment time, likely due to variation in lesion consistency (soft, medium, or hard), which necessitated repeated applications of the BRIX3000® gel, most commonly 2–3 times per case, followed by mechanical excavation of the infected dentin. In some cases, conventional drills were used to get access to the lesion in the presence of undermined enamel. A ceramic bur is composed of alumina–yttria ceramic, which exhibits excellent wear resistance and cutting ability. Multiple studies have demonstrated that this material allows faster caries removal compared with CMCR.22, 29, 36 Therefore, the CMCR method may be associated with higher levels of anxiety, as it requires a longer treatment duration.37 Although the SDF method was more time-consuming than the CeraBur® technique, the latter requires the administration of dental anesthesia, which contributes substantially to the overall treatment time (Figure 6) and may negatively influence the child behavior. In contrast, the SDF method demonstrated a shorter duration than the CMCR procedure, as it involved tooth cleaning and manufacturer-standardized application times. Treatment duration was dependent on the number of applications required, with a maximum of 2 applications per tooth. These findings are consistent with those reported by Vollú et al.35

The adverse events recorded in the present study included discoloration of the teeth and gingiva, pain and tooth sensitivity during the 2-week follow-up, as reported by the parents. As has been demonstrated in a number of studies,35, 38, 39 discoloration was identified as an adverse event in the majority of cases. However, in 1 study, this was not considered to be the case, and the reported side effects were either diarrhea or stomachache after SDF treatment.40

Regarding that adverse events were significantly more prevalent in the e-SDF® group, they included only discoloration of gingival tissues that resolved within 2 days, and black staining on the arrested lesions of teeth. The absence of pain and sensitivity was also noted. These outcomes are similar to those reported in the studies by Vollú et al., Fung et al. and Duangthip et al.35, 38, 39 Despite the cosmetic effects of SDF, parents were informed about the effects of other treatment methods and were given information to help them make an informed choice and weigh up the advantages of SDF’s non-invasiveness with the aesthetic concerns.

The remaining treatment groups (CeraBur® and BRIX3000®) exhibited pain and sensitivity in 13% of cases. Although these symptoms do not necessarily indicate serious or irreversible damage, they may still have clinical relevance. Moreover, parental reports of children’s symptoms may be subject to misinterpretation, either underestimating or overestimating their severity and duration, which may range from transient to more persistent. Although these 2 groups show relatively low frequency of adverse events, the presence of pain and sensitivity may be associated with residual caries and can negatively affect the child’s quality of life, representing a more significant concern than discoloration alone. In this context, despite the undesirable dark staining associated with SDF, its benefits (such as caries arrest and non-invasiveness) are considered to outweigh the cosmetic drawbacks.41

Numerous minimally invasive procedures, including ART, involve hand instrument-based excavation of carious tissue followed by cavity restoration without the use of bonding agents. These approaches have demonstrated good biocompatibility, particularly when a cement is used, and high thermal expansion.42 Nevertheless, the application of SDF results in tooth discoloration, potentially compromising aesthetic appeal. This highlights the need for restorative materials that effectively improve aesthetics while maintaining efficacy.41 A tooth-colored GIC containing a high concentration of fluoride ions, which remineralize carious lesions and prevent further caries development, can also be utilized to arrest active caries.

The follow-up examinations were conducted at 3 months following the assessment rating adapted from the study by Satyarup et al.28 The integrity of restorations post-treatment could be affected by the efficacy of caries removal, the extent of caries, cavity dimensions, tooth location, and the type of cavity, given that mastication affects restoration durability.

Although the e-SDF® group showed better retention of the GIC restoration, it can be attributed to the fluoride released from SDF, which enhances dentin resistance and reduces acid penetration.43 Silver diamine fluoride has antibacterial and remineralizing properties that strengthen the marginal integrity, which is an important factor in the management of deep carious dentin.44 The study results showed that the differences were borderline significant between the groups and that was in harmony with the studies by Raskin et al., Satyarup et al. and Zhi et al.28, 45, 46 This dissimilarity may be attributed to the short-term 3-month follow-up, whereas the other studies implemented 6-month follow-ups for the evaluation of GIC restoration.

Riva Self Cure glass ionomer cement is a high-viscosity glass hybrid material that demonstrates a high clinical success rate and significantly reduced microleakage in Class II slot cavities, with performance comparable to that observed in Class I cavities.47, 48, 49 In the course of our study, teeth with Class I and Class II slot preparations were evaluated. Based on these findings, high-viscosity GIC can be recommended as a reliable restorative option for Class I and Class II restorations in short-term follow-up. However, long-term clinical studies are required to further assess the survival rate of GICs in Class II cavities.50

A longer follow-up period would offer further explanation and could change the results regarding secondary caries, marginal mechanical wear or durability of GIC restoration.51 However, there would be an increased risk of attrition and drop-out problems in follow-up among study cases.

The findings of the present study reveal that there is no statistically significant difference between the CeraBur® and BRIX3000® methods of caries removal based on restoration integrity. A study by Alkhawaja and Al Haidar showed that CeraBur® and BRIX3000® exhibited comparable performance in terms of microleakage of glass ionomer restoration. Both treatment groups focused on the removal of infected dentin, without exerting an effect on the remineralization of the lesion.20 Another study concluded that there was no difference regarding residual dentin (smear layer, surface irregularities, intertubular microporosities, and exposed tubules) between smart burs and BRIX3000® after caries excavation, a process that affects the restorative material retention.52

Limitations

The sample of the study was limited to schoolchildren aged 7–8 years. This may constrain the generalizability of the findings to other populations. The study was conducted over a period of 3 months; longer follow-up periods are recommended to obtain a clearer idea about the retention and mechanical wear resistance of restorations. Certain outcomes, such as anxiety level, were not measured, as a separate study will be conducted on this aspect. The effectiveness of BRIX3000® and e-SDF® in reducing Streptococcus mutans count was not assessed. Further studies could explore the cost-effectiveness of SDF as opposed to other minimally invasive techniques.

Conclusions

Among the minimally invasive procedures evaluated in this study, the use of the ceramic bur resulted in the shortest treatment time. Caries excavation using BRIX3000® required a longer duration compared with both the ceramic bur and SDF application. The utilization of CMCR may be considered an alternative to conventional caries removal techniques, as it minimizes the need for local anesthesia. The only noticeable issue reported by parents regarding SDF application was tooth discoloration.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the College of Dentistry of the Mustansiriyah University (Baghdad, Iraq) (No. MUPRU004). Prior to participation, parents or legal guardians were provided with comprehensive information about the study design, objectives and potential benefits. Written informed consent was obtained, and parents or guardians were informed of their right to withdraw their child from the study at any time.

Trial registration

The trial protocol was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (registration ID: NCT06412731; https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06412731).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.