Abstract

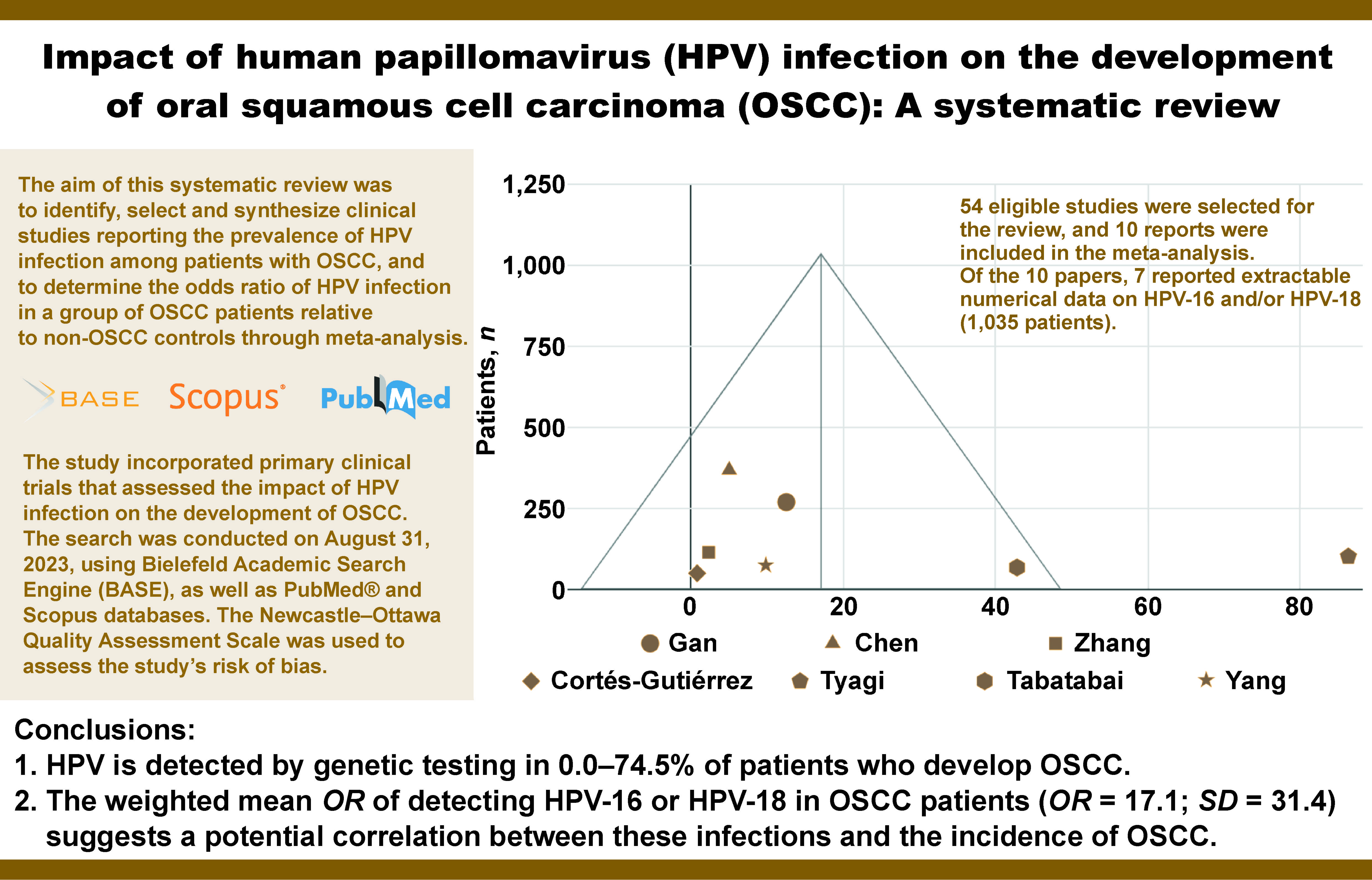

This systematic review aimed to identify, select and synthesize clinical studies reporting the prevalence of HPV infection among patients with OSCC, and to determine the odds ratio (OR) of HPV infection in a group of OSCC patients relative to non-OSCC controls through meta-analysis.

The study incorporated primary clinical trials that assessed the impact of HPV infection on the development of OSCC. The search was conducted on August 31, 2023, using Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE), as well as PubMed® and Scopus databases. The Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used to assess the risk of bias of the included studies. The collected data was then synthesized in the form of tables and a funnel plot. A total of 54 eligible studies were selected for the review, and 10 reports were included in the meta-analysis. Of the 10 papers, 7 reported extractable numerical data on HPV-16 and/or HPV-18 (1,035 patients).

The limitations of the evidence included the following: inhomogeneity in terms of HPV type; small number of available controlled studies (not homogeneous in terms of virus type); small number of patients on whom controlled studies were conducted; and the risk of bias related to the selection of study and control groups (present in most studies qualified for the synthesis).

In conclusion, HPV is detected by genetic testing in 0.0–74.5% of patients who develop OSCC. The weighted mean OR of detecting HPV-16 or HPV-18 in OSCC patients (OR = 17.1; standard deviation (SD) = 31.4) suggests a potential correlation between these infections and the incidence of OSCC.

Keywords: HPV, OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma, systematic review, human papillomavirus

Introduction

Background

Head and neck cancers account for over 5% of all malignancies.1 This category includes cancers of the oral cavity, throat, larynx, paranasal sinuses, thyroid and salivary glands, as well as the surrounding soft and hard tissues.2, 3 Approximately 90% of cancers in this category are squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs).3

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a term used to describe cancers with squamous cell differentiation developing within the oral mucosa and lips, excluding the skin of the mouth and the pharyngeal mucosa. Oropharyngeal SCC (OPSCC) refers to cancers located in the palatine tonsil, the root of the tongue, the glossotonsillar groove, and the mucous membrane of the lateral and posterior pharyngeal walls. In some publications,4 the term OPSCC is used imprecisely to describe both cancer of the oral cavity and cancer of the oropharynx. However, current evidence supports the conclusion that OSCC and OPSCC are distinct and unique, with differing etiopathogenesis, treatment and prognosis.3

The risk of OSCC increases significantly after the age of 50, and the condition is diagnosed 3 times more often in males.5 Despite advancements in technology, including self-learning systems, detecting oral cancer at an early stage remains challenging for clinicians.6 Therefore, the identification of OSCC risk factors seems particularly important. The influence of tobacco smoking and chronic alcohol consumption on the development of OSCC has been extensively documented.7 Additional significant risk factors include poor oral hygiene, chronic irritation of the mucous membrane due to faulty prosthetic restorations or dental fillings, candidiasis, and the presence of potentially malignant disorders such as leukoplakia, lichen planus or erythroplakia.8, 9

Rationale

In recent years, there has been a sharp increase in the incidence of OSCC among patients in younger age groups (approx. 20–40 years) who developed OSCC despite good oral hygiene and the absence of any of the aforementioned risk factors.5, 10 Current research on the impact of head and neck cancer on the quality of life confirms that available treatment leads to its permanent deterioration (e.g., it induces sexual issues, which are of particular importance to this age group).11 It has been speculated that in this group of patients, another initiator may be responsible for promoting the carcinogenesis process, and it is currently under debate whether high-risk human papillomavirus infection (HR-HPV) plays a role in the development of OSCC.12 This hypothesis is related to the fact that, in relation to OPSCC, i.e., cancers developing in the immediate anatomical vicinity of the oral cavity, there is clear scientific evidence of the impact of HR-HPV infection on the development of cancer.2 Recent studies have indicated that up to 70% of OPSCC cases are related to HR-HPV infection, primarily types 16 and 18.13 However, the relationship between HPV infection and OSCC is still unclear.14 The frequency of OSCC cases in which HR-HPV genetic material is detected, according to various authors, ranges between 2.6%15 and 74%.13 However, in most of the analyzed samples, HPV is detected in over 25% of OSCC cases.16

Revealing a direct relationship between viral infection and the occurrence of OSCC would have significant clinical implications. In the context of OPSCC, HPV(+) cancers are characterized by a less aggressive course and significantly better survival outcomes compared to HPV(−) cancers. Consequently, therapeutic interventions in this group of patients may be less invasive.17, 18

Aim

The aim of this systematic review was to identify, select and synthesize clinical studies reporting the prevalence of HPV infection among patients with OSCC, and to determine the odds ratio (OR) of HPV infection in a group of OSCC patients relative to non-OSCC controls through meta-analysis. The collection of this data is intended to indirectly assess whether the risk of OSCC is greater in HPV-positive individuals.

Material and methods

This systematic review is based on and arranged in accordance with the current version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.19 The completed PRISMA checklist and the PRISMA checklist for abstracts constitute the supplementary material to this article (available on request from the corresponding author). This systematic review has been registered in the PROSPERO database (registration No. CRD42023483769).

Eligibility criteria

Primary clinical trials published in English that evaluated the impact of HPV infection on the development of OSCC were included. The detailed eligibility criteria are presented in Table 1, albeit the Control and Outcomes criteria only concerned the inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Information sources

A comprehensive search of medical databases was conducted using the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE), PubMed® and Scopus. All final searches were performed on August 31, 2023.

Search strategy

The search strategy, identical for each of the engines, was formulated based on the eligibility criteria and arranged in the form of the following query: (“oscc” OR “oral scc” OR “oral squamous cell carcinoma”) AND (“hpv” OR “papillomavirus” OR “papilloma virus”) AND (“correlation” OR “correlated” OR “effect” OR “affects” OR “impact” OR “influence” OR “link” OR “connection”) AND (“study” OR “trial” OR “primary”).

Article selection

The identified records were entered into the Rayyan automation tool (Rayyan Systems, Cambridge, USA).20 The duplicates were automatically removed, and the records indicated by the tool as potential duplicates were manually verified (IR and MC). A blind screening of abstracts and titles was performed by 2 researchers (IR and MC). The convergence of researchers’ ratings was expressed by Cohen’s kappa coefficient. In cases of non-compliance during the screening stage, the record underwent further processing. The full-text reports were evaluated by the same researchers (IR and MC). Discrepancies that emerged during the full-text evaluation phase were resolved through consensus.

Data collection

The data was extracted from the source articles by 2 independent authors (IR and MC). The present study exclusively utilized published data, specifically the content of articles and supplementary materials. The collection process did not involve the use of automation tools.

Extracted characteristics of the studies

The following items were extracted from the source studies: first author and year of publication; sex and average age of patients; OSCC location; total number of patients in the OSCC group; number of patients in the OSCC group with genetically confirmed HPV; total number of patients in the non-OSCC group; number of patients in the non-OSCC group with genetically confirmed HPV; OR between HPV and OSCC.

Assessment of the risk of bias

The Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used to assess the risk of bias for studies included in the meta-analysis. The evaluation was performed by 2 independent researchers (IR and MC). Any discrepancies in assessment were resolved through consensus, and no automation tools were implemented in the process.

Effect measures

For studies with a control group, the OR was calculated using the MedCalc Statistical Software v. 22.018 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium).

Data synthesis

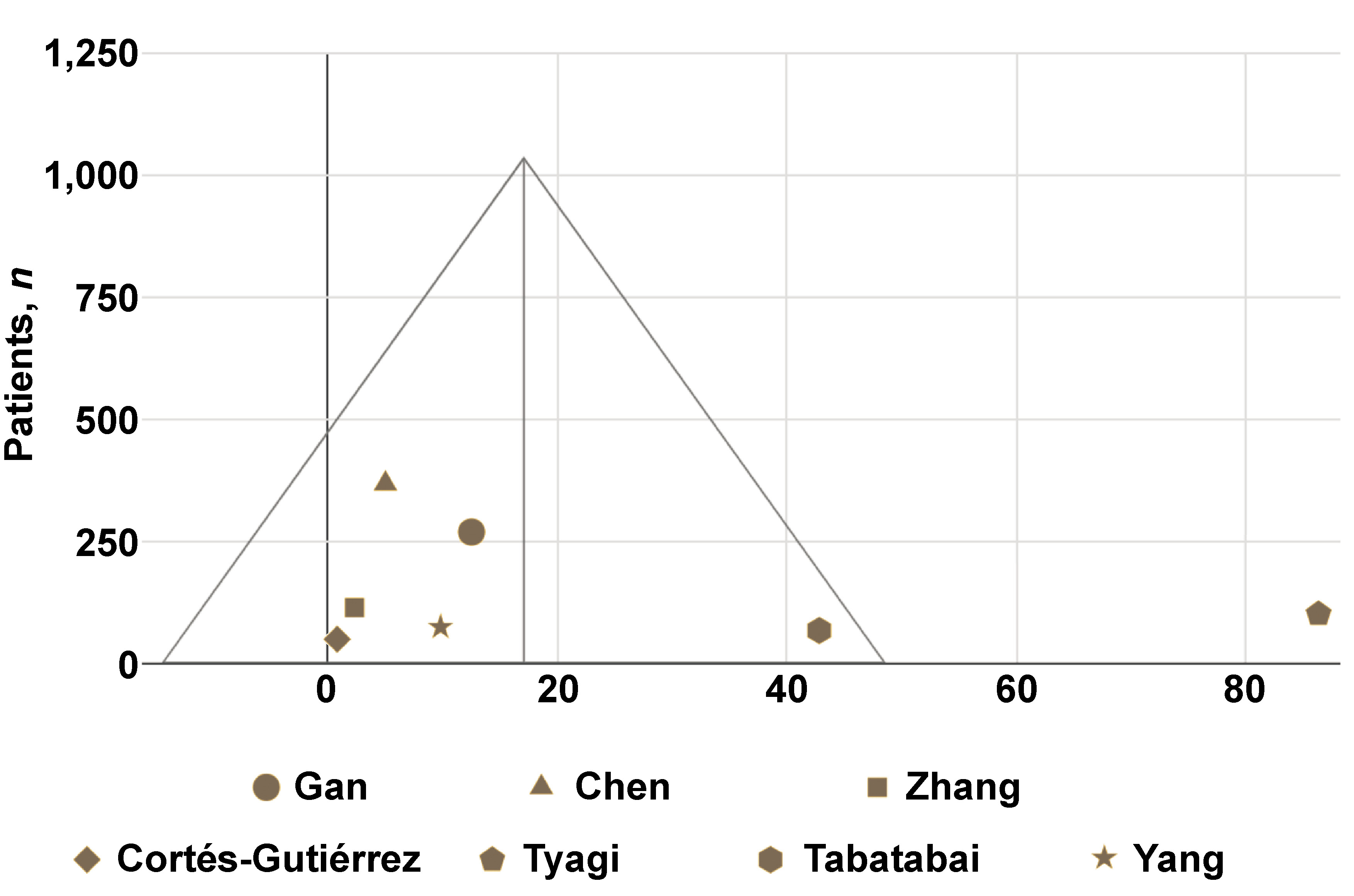

The collected data was synthesized in the form of tables and a funnel plot using Google Workspace (Google LLC, Mountain View, USA).

Reporting the assessment of bias

In instances of missing data, this fact was noted, yet the series was not discarded. No further reporting bias assessments were undertaken.

Results

Study selection

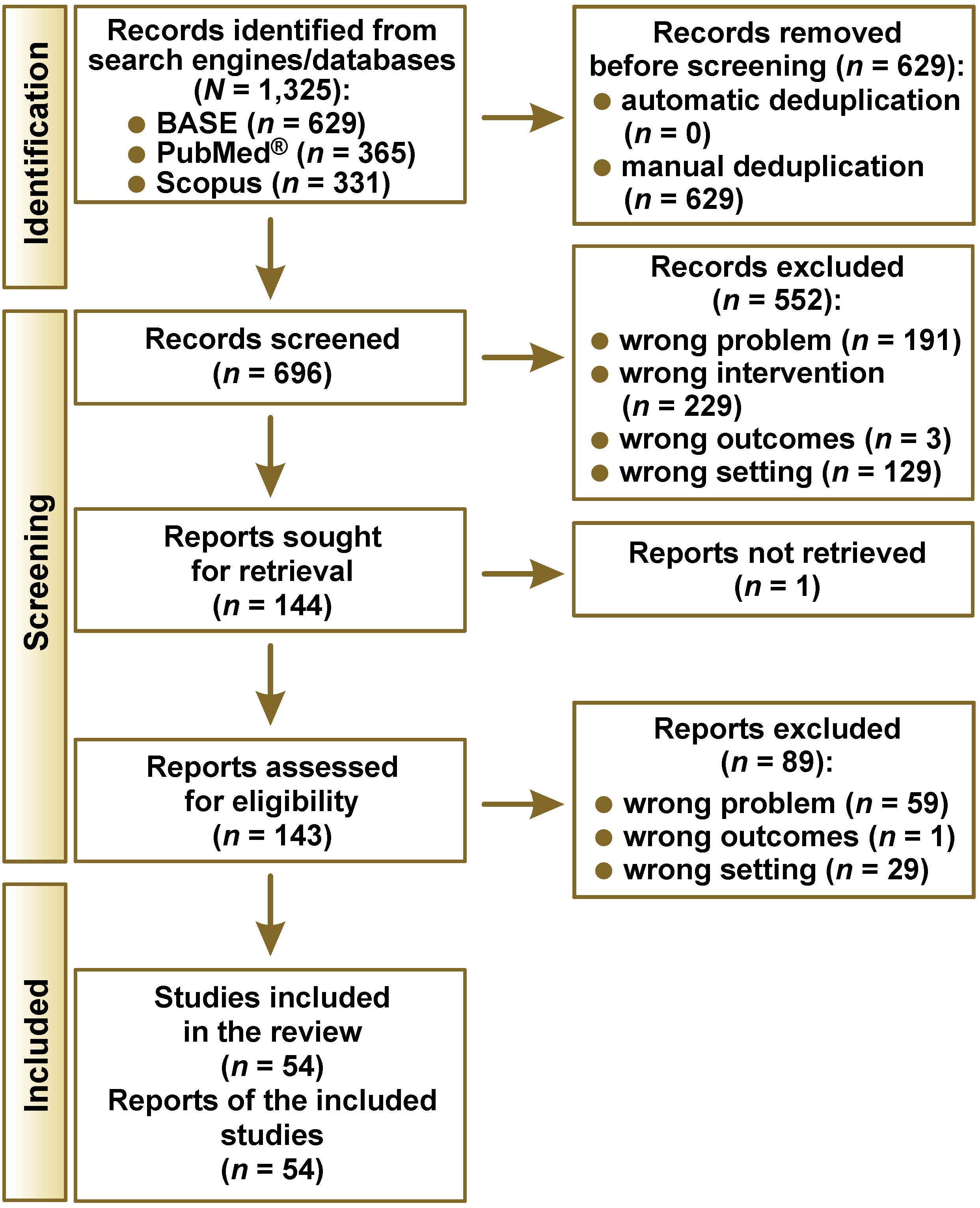

The number of records identified from each search engine/database is presented in Table 2. During the selection process, 54 eligible studies were selected out of 1,325 identified records (Figure 1). The consistency index of the judges’ assessments at the screening stage was κ = 0.87, which represents almost perfect agreement. The study by Cao et al. was considered eligible based on the abstract, but its full text was not obtained due to the lack of digital archiving of articles from these years in the Chinese Journal of Dental Research.21

Study characteristics

Fifty-four studies included in the review are summarized in Table 3. Each study considered different locations of OSCC, making it impossible to create subgroups based on specific areas of the oral cavity. The collected material covered clinical trials since 1996, which resulted in an overview of over a quarter of a century of active research on the relationship between HPV infection and the occurrence of OSCC. The study samples did not exceed 254 patients, and most reports were based on material from fewer than 100 subjects. The preponderance of single-center studies made it challenging to extrapolate results to broader populations. The percentage of diagnosed HPV infections in OSCC patient groups fluctuated significantly (0.0–74.5%), which was partly related to the limited sample size and the heterogeneity of the identified virus types. The majority of the papers did not include a control sample and were limited to a single arm, precluding the possibility of synthesizing them to ensure a high level of evidence for the review. Therefore, studies incorporating a control group advanced to further stages of the review.

Risk of bias

The Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale scores for each of the studies included in the meta-analysis ranged from 6 to 9 (maximum) points (Table 4). Therefore, the overall risk of bias for the studies was low or raised some concerns. The ratings were decreased primarily due to the absence of statements regarding the inclusion of consecutively reporting patients and limited information on the control groups.

Results of individual studies

The results of individual studies are outlined in Table 5. Most studies had symmetrical sample sizes, though there were exceptions to this rule. The number of patients in the study groups ranged from 30 to 200, which enabled quantitative analysis. Depending on the study, the sex ratio was either similar or men predominated by up to 2.5 times. The percentage of HPV infections in the control samples did not exceed 55%. In numerous reports, the prevalence of HPV infection in the control sample was negligible or equal to 0. In each study sample, HPV was detected in at least 1 patient, and the percentage of infected individuals reached up to 74%. Interestingly, a study that encompassed a broader range of virus types observed a lower infection rate in comparison to the maximum recorded value.42 This could be due to the lack of identification of HPV-18, which is present in the majority of tests conducted by other research groups. Discrepancies can be observed in relation to the type of identified virus, with a clear dominance of HPV-16 and HPV-18. In studies with smaller sample sizes, the OR did not attain statistical significance. In cases with confirmed statistical significance, the OR ranged from 2.3 to 86.3, indicating a higher probability of identifying HPV in materials from patients diagnosed with OSCC.

Results of data synthesis

Of the 10 reports containing numerical data that enabled OR calculation, 8 assessed HPV-16 and/or HPV-18; however, only 7 studies provided extractable data specific to HPV-16 or HPV-18. The OR results for HPV-16 and HPV-18 were synthesized in a funnel plot (Figure 2). This synthesis was based on a total of 1,035 patients. The weighted mean OR was 17.1 (standard deviation (SD) = 31.4). The OR result reported in the study by Tyagi et al. was an outlier.

Discussion

General interpretation of the results

In the collected research material, the percentage of OSCC patients infected with HPV ranged from 0.0% to 74.5%. Significant discrepancies in the results have been confirmed in other reviews.65, 66 The discrepancies are likely attributable to the testing of different types of the virus within individual clinical trialws. Moreover, the method of testing for the HPV genome, even of the same type, is not uniform, which may be the reason for differences in the results presented by different teams of researchers.

Of the 54 eligible studies, only 10 included a control group. The ideal study design would involve a study group and a control group that are matched in terms of sex and age. In the available material, control groups were selected primarily from patients of the same institution (but not from the general population).

The results of the OR for the presence of the HPV genome in OSCC vs. non-OSCC patients indicate the presence of a relationship between the occurrence of OSCC and HPV-16 or HPV-18 infection. With the exception of the study by Cortés-Gutiérrez et al.,15 which was conducted on a small group of patients, the OR for the HPV-16 and HPV-18 in OSCC vs. non-OSCC groups is greater than 1, indicating a higher probability of detecting these types of virus in patients with OSCC. Based on the patient-derived outcomes, it was confirmed that a positive result for HPV-16 and/or HPV-18 is associated with a significant risk of developing OSCC.

The collected research material is insufficient to draw similar conclusions regarding other types of the virus. The study by Yang et al. showed no statistically significant relationship between the incidence of OSCC and the presence of HPV-67 or HPV-68 infection.24

Biological risk factors for OSCC

The current state of knowledge suggests a correlation between HPV and the risk of OSCC, which is the subject of this paper. Additionally, an increased predisposition to OSCC is suspected in patients infected with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).56 A similar relationship has been observed among individuals infected with bacteria that cause periodontitis, i.e., Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum. However, there is a lack of clinical evidence for this relationship, and assumptions are solely based on in vitro and animal studies.67 The previously ambiguous relationship between Candida spp. infection and the development of OSCC was confirmed in a systematic review from 2023.68 The demonstrated correlation supports the possibility of causality, which requires further research.

HPV diagnostics

The gold standard for the diagnosis of HPV infection is the identification of the genetic material of the virus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). An alternative method involves the identification of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16) protein immunohistochemically.16 A meta-analysis of diagnostic methods for oral HPV showed high sensitivity but moderate specificity of immunohistochemical identification.69 It is, therefore, accepted that the detection of p16 is of high value as a screening test, but may not be sufficient for scientific purposes. The present systematic review was based solely on source studies, in which the presence of HPV genetic material in patient tissues was confirmed by PCR.

Benign lesions

The infection with HPV may also contribute to the development of benign lesions, commonly referred to as oral warts. These include, among others, focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck’s disease), squamous cell papilloma of the oral cavity, common wart (verruca vulgaris), and condyloma acuminata of the oral cavity.70 For a progression to a malignant state, the presence of appropriate co-factors is necessary, including genetic predisposition, smoking and alcohol consumption.71

The significance of HPV infection in oral potentially malignant lesions, specifically in leukoplakia, remains unclear.72 A recent systematic review has estimated the overall HPV prevalence in leukoplakia at 6.66%, whereas the prevalence of HPV-16 at 2.95%.73 However, the current update from the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of head and neck tumors distinguishes the HPV-associated dysplasia as a separate lesion, with about 15% risk of malignant transformation.74, 75

Future research

A particular emphasis must be placed on the methodological problem that is present in all qualified studies. The authors of the source papers attempted to estimate the risk of OSCC among HPV(+) vs. HPV(−) patients by designing studies in which the presence of the viral genome was determined in OSCC and non-OSCC patients. In order to most appropriately investigate the incidence of OSCC among patients with HPV, a long-term follow-up of HPV(+) vs. HPV(−) cohorts in the context of OSCC occurrence is necessary. It is important to consider the possibility of HPV infection during observation, and to differentiate between the various types of the virus.

Limitations of the evidence

The limitations of the evidence included the following: inhomogeneity in terms of HPV type; small number of available controlled studies (not homogeneous in terms of virus type); small number of patients on whom controlled studies were conducted; and the risk of bias related to the selection of study and control groups (present in most studies qualified for the synthesis).

Limitations of the review process

The main limitation of the review process included the use of a query in English, thereby excluding reports that lacked at least a title or abstract in this language. Moreover, the search engine and databases used do not ensure the identification of articles published in locally indexed journals.

Conclusions

Human papillomavirus is detected through genetic testing in 0.0–74.5% of patients with OSCC. The weighted average OR for detecting HPV-16 or HPV-18 in OSCC patients is 17.1, suggesting that these viral variants may contribute to the development of OSCC.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.