Abstract

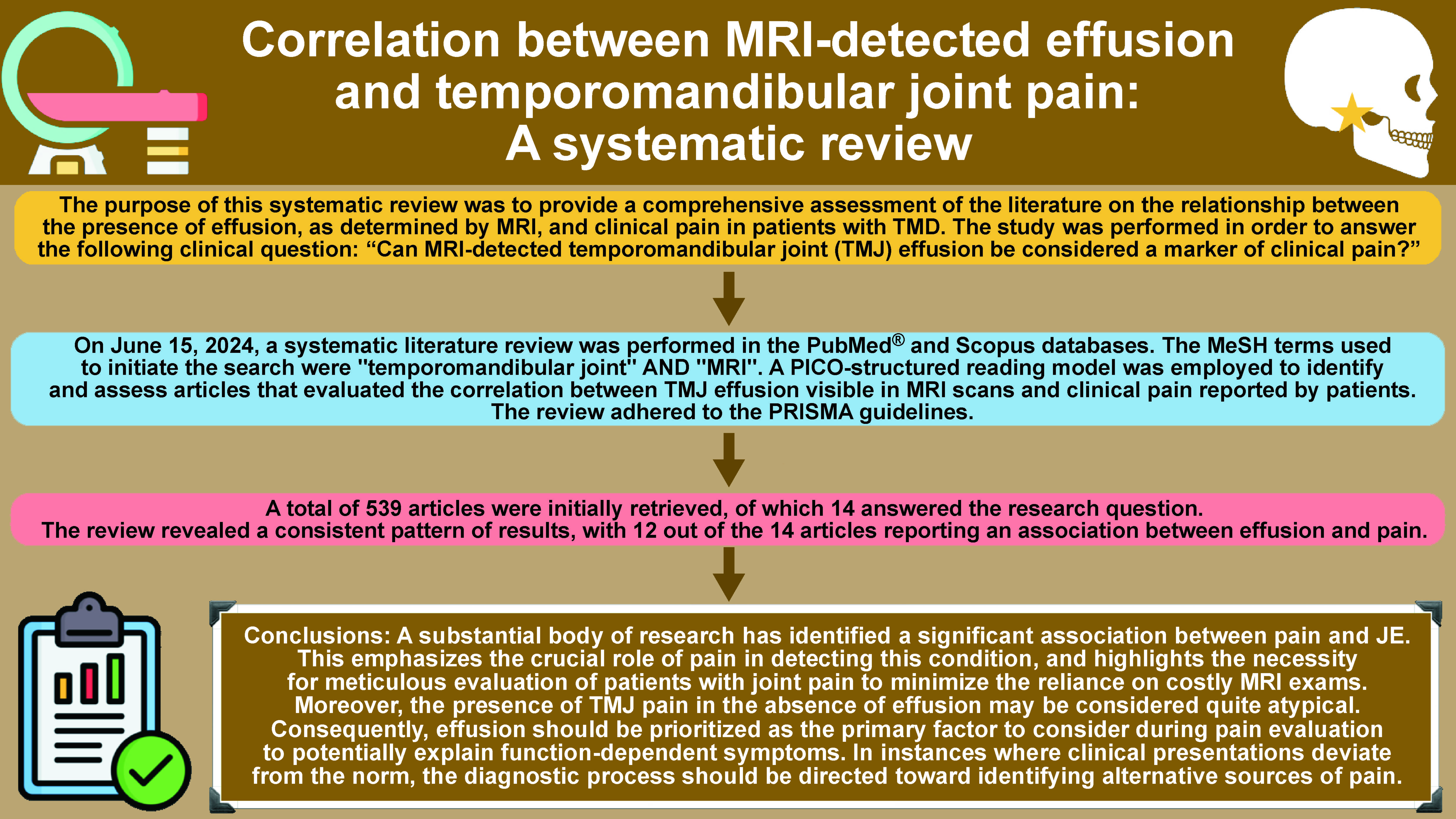

The purpose of this systematic review was to provide a comprehensive assessment of the literature on the relationship between the presence of effusion, as determined by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and clinical pain in patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD). The study was performed in order to answer the following clinical question: “Can MRI-detected temporomandibular joint (TMJ) effusion be considered a marker of clinical pain?”

On June 15, 2024, a systematic literature review was performed in the PubMed® and Scopus databases. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms used to initiate the search were “temporomandibular joint” AND “MRI”. A PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) structured reading model was employed to identify and assess articles that evaluated the correlation between TMJ effusion visible on MRI scans and clinical pain reported by patients. The review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A total of 539 articles were initially retrieved, of which 14 answered the research question. The review revealed a consistent pattern of results, with 12 out of the 14 articles reporting an association between effusion and pain.

The findings indicate that there is a link between the occurrence of effusion and the experience of pain in individuals diagnosed with TMD.

Keywords: effusion, temporomandibular joint disorder, magnetic resonance, temporomandibular joint pain

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) encompass a group of conditions that affect the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles and associated structures.1 These disorders manifest clinically as pain, limited jaw movement, joint noises (clicks), and functional impairment.2 They are associated with substantial patient discomfort and reduced quality of life. Therefore, research is necessary to provide the best possible care to affected individuals. The association between joint disorders and various clinical and radiological signs and symptoms has been extensively documented in medical literature.3 Intra-articular joint disorders can be linked to clinical conditions, such as disc displacement (with or without reduction) and radiological signs, including sclerosis, erosion, osteophytes, and subcortical cysts.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a valuable diagnostic tool for TMJ pathology due to its superior ability to visualize soft tissue conditions compared to other methods.5 The tool can provide information about the location of the disk,6 synovial fluid quantity,7 and the condition of the retrodiscal tissues and bone marrow.8 The majority of MRI studies has focused on signal changes within joint compartments.9 These alterations indicate the presence of fluid resulting from the inflammation of retrodiscal tissues and other inflammatory changes in the synovial membrane, which can lead to joint effusion (JE).10 The clinical assessment of pain and the study of its correlation with MRI findings is a key factor to guide the diagnostic and therapeutic dimensions of TMD management.7 An enhanced understanding of the connection between the presentation of clinical pain and the imaging features revealed by MRI can greatly influence treatment decisions and help tailor interventions to address the specific needs of individual patients.11, 12

The aim of this systematic review is to examine the existing literature to address the clinical question of whether effusion observed on MRI can be considered a marker for arthralgia.

Material and methods

Research strategy

A systematic review of the literature published until June 2024 addressing the relationship between the presence of TMJ effusion on MRI and pain reported by patients with TMD was carried out in the PubMed® and Scopus databases. The review process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.13 The research has been registered with PROSPERO (ID No. CRD42024558402). Studies referenced within the reviewed articles were also included if they met the established inclusion criteria. The database search used a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms as well as expansion strategies based on the evaluation of reference lists of included articles and authors’ personal libraries:

– (“temporomandibular joint”[MeSH Terms] OR (“temporomandibular”[All Fields] AND “joint”[All Fields]) OR “temporomandibular joint”[All Fields] OR “tmj”[All Fields]) AND (“magnetic resonance imaging”[MeSH Terms] OR (“magnetic”[All Fields] AND “resonance”[All Fields] AND “imaging”[All Fields]) OR “magnetic resonance imaging”[All Fields] OR “mri”[All Fields]);

– (“magnetic resonance imaging”[MeSH Terms] OR (“magnetic”[All Fields] AND “resonance”[All Fields] AND “imaging”[All Fields]) OR “magnetic resonance imaging”[All Fields] OR “mri”[All Fields]) AND (“temporomandibular joint”[MeSH Terms] OR (“temporomandibular”[All Fields] AND “joint”[All Fields]) OR “temporomandibular joint”[All Fields]) AND (“effusate”[All Fields] OR “effusates”[All Fields] OR “effused”[All Fields] OR “effusion”[All Fields] OR “effusions”[All Fields] OR “effusive”[All Fields]);

– (“magnetic resonance imaging”[MeSH Terms] OR (“magnetic”[All Fields] AND “resonance”[All Fields] AND “imaging”[All Fields]) OR “magnetic resonance imaging”[All Fields] OR “mri”[All Fields]) AND (“temporomandibular joint”[MeSH Terms] OR (“temporomandibular”[All Fields] AND “joint”[All Fields]) OR “temporomandibular joint”[All Fields]) AND (“edema”[MeSH Terms] OR “edema”[All Fields] OR “edemas”[All Fields] OR “oedemas”[All Fields] OR “oedema”[All Fields]).

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria encompassed clinical trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, and case series that investigated the correlation between MRI effusion in the TMJ and pain, and were published in English. The following types of publications were excluded from the analysis: systematic reviews or meta-analyses; non-systematic reviews; case reports; expert opinions; letters; studies that did not report a correlation between effusion and pain; studies that reported data from previous publications; opinion papers; letters to the editor; and articles published before 1990.

Assessment of papers

The literature screening was carried out using a systematic approach to identify all relevant articles. During the review process, the titles and abstracts were initially screened (TiAb screening), followed by the full-text reading of the papers that passed the filter. The process was carried out by 3 different reviewers (FS, NGS, MV) who worked separately and later discussed their differences. The full texts of the articles that met the eligibility criteria were retrieved and thoroughly reviewed together with the review coordinator (DM). The following data was extracted: author(s); year of publication; study design; sample size; sex and age of participants; follow-up period; outcome variables; and results.

The articles were analyzed by adopting a PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) strategy for structured reading, based on the following question: In individuals diagnosed with TMD (P), does the presence of effusion (I), as compared to joints without effusion (C), correlate with the reported pain experienced by the patients (O)? A descriptive analysis was subsequently conducted on the selected studies.

Assessment of study quality

The grading of the level of evidence was based on the work of Sackett, as summarized in Table 1.14

Statistical analysis

The substantial heterogeneity of the included studies precluded the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis. Thus, the present systematic review was subjected to a descriptive analysis. EndNote 20 (Clarivate Analytics, London, UK) was employed to organize the reviewed studies, while Microsoft Excel (v. 16.93.1 for Apple; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) was utilized to catalog the results and characteristics of the selected studies.

Results

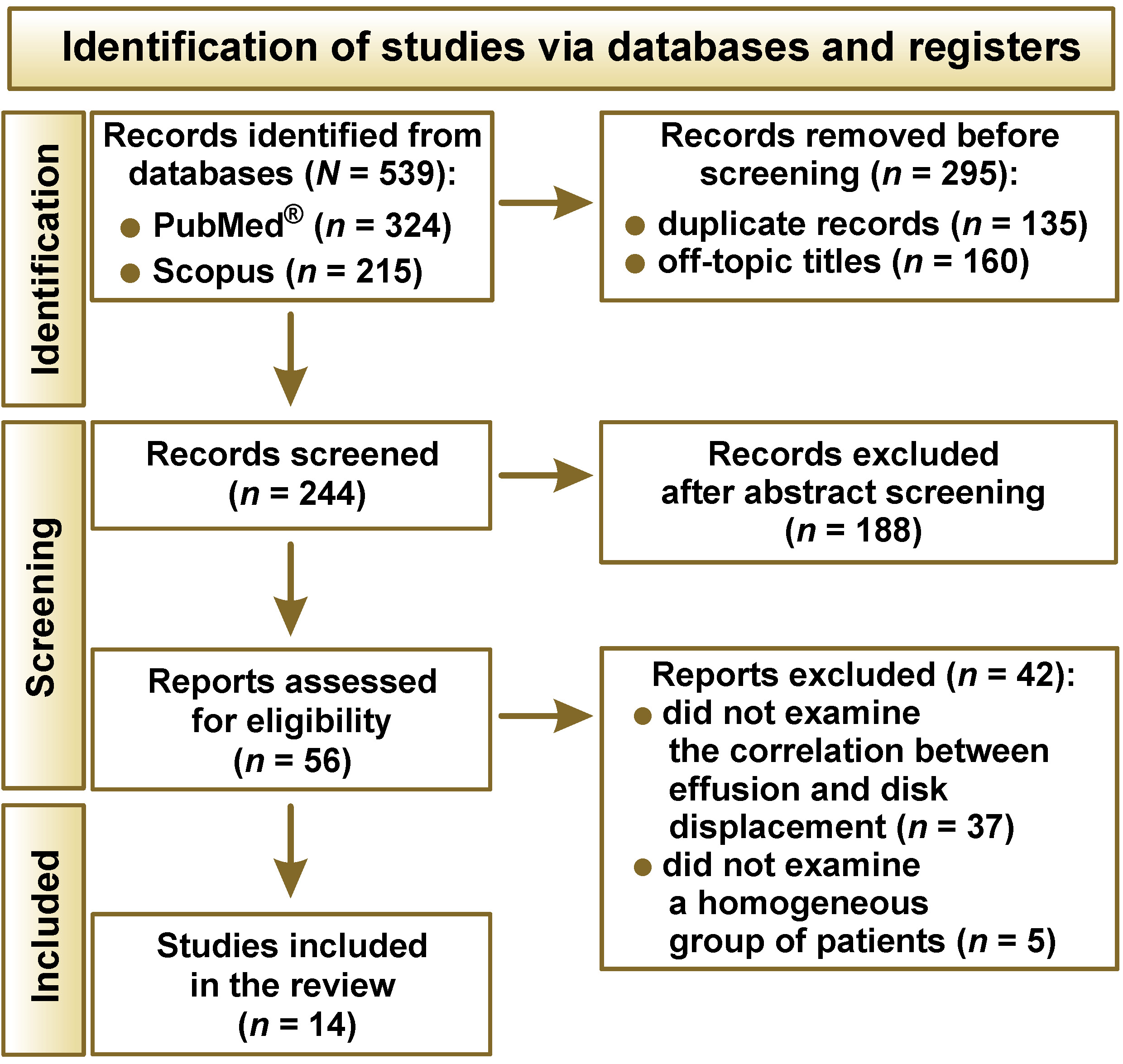

A total of 539 articles were identified, and 295 papers were excluded after an initial screening of titles. Subsequent analysis of the abstracts of the remaining articles resulted in the exclusion of an additional 188 studies. The final step involved a thorough review of the full text of 56 articles. Of these, 37 articles did not study the variables of interest, and 5 articles assessed a population that was not homogeneous, leading to a total of 14 papers included in the review. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Study characteristics

Table 2 displays the characteristics of the included studies.

A wide variation in the composition of the different study groups was identified. The majority of articles included only populations of individuals with unspecific TMJ pain, either bilateral7, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 or unilateral.21, 22, 23 However, 2 studies21, 24 focused exclusively on patients who exhibited symptoms of TMJ pain, TMJ clicks, and limited mandibular opening. One study included only patients with clinical signs and symptoms of disc displacement with reduction (DDwR).25 Díaz Reverand et al. recruited patients with painful TMJ disease who underwent unilateral arthroscopy and had both preoperative MRI and clinical follow-ups conducted at 3, 6 and 12 months post-surgery.26 Symptomatic patients with internal derangement who did not respond to conservative treatment were recruited by Fernández-Ferro et al.,27 while Roh et al.20 adopted a random selection approach when choosing MRI scans from patients with TMD.

The vast majority of studies employed a 1.5T machine. Exceptions were observed in the studies by Hosgor et al.23 and Manfredini et al.,7 which relied on a 0.5T system; Yamamoto et al.,19 who additionally incorporated a 1.0T scanner; and Matsubara et al.,15 who also employed a 3.0T machine. A high degree of similarity was observed in the sequencing techniques used in the studies. Almost all studies assessed both T1- and T2-weighted images in closed- and open-mouth positions.

Quality of the selected studies

Table 3 depicts a predominance of low-level (level III/IV) evidence within the included studies.

Effusion and pain

The reviewed papers consistently reported an association between JE, as observed on MRI, and clinical pain, with minor exceptions. Studies by Güler et al.21 and Pinto et al.25 did not report any association between JE and pain. Hosgor noted a relationship between marked effusion and pain, but was unable to identify a statistically significant correlation between moderate effusion and pain.23

Discussion

The attempt to identify a correlation between clinical symptoms and radiological signs on MRI is a highly sensitive topic in the literature. Numerous articles have endeavored to correlate disc displacement and JE.11, 28, 29 The potential for a psychologically modulated condition in patients experiencing TMJ pain without signs of effusion was also investigated.30 On the other hand, the presence of intra-articular fluid, as detected by MRI, remains a subject of debate in relation to its association with TMJ pain. It has been suggested that a certain amount of TMJ effusion may be present among asymptomatic individuals,31 but JE is considered a radiological sign of osteoarthritis when accompanied by cortical bone erosion and/or productive bone changes, thus making it worthy to explore as a source of clinical findings.32 The prevalence of TMJ effusion in patients with TMJ pain ranged from 13% to 88%, whereas prevalence rates in TMJs without pain ranged from 0% to 38.5%.21, 33, 34, 35, 36

The review revealed a statistically significant correlation between JE and pain in 12 of the 14 papers examined.7, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27 Among the papers reporting a correlation, Hosgor conducted a study on 240 TMJs from 120 patients, noting a statistically significant difference in TMJ pain levels between patients with severe JE and individuals without effusion.23 Among the negative studies, Güler et al. did not identify a significant correlation between pain and dysfunction levels and JE and total protein concentration, either in control or study groups (p > 0.05).21 However, it is important to note that this study was conducted on only 31 patients. Further research with a larger sample size is necessary to obtain conclusive results. Pinto et al. failed to establish a correlation between pain and JE.25 However, 71% of the patients exhibited moderate to severe pain (i.e., visual analogue scale (VAS) > 5), indicating the necessity for further data refinement.25

The results, as well as the partial heterogeneity of findings, may be related to the non-homogeneous approach to pain diagnosis and clinical evaluation. The subjective nature of pain, influenced by the psychological status of the patient and the different approaches to its diagnosis, may also play a role. It has been observed that certain patients who report pain in the TMJ area in the absence of effusion may be experiencing this discomfort due to a condition that is psychologically modulated.30 This finding suggests that a careful evaluation of the patient’s psychological status might be necessary along with a thorough physical and imaging examination.

The clinical management of TMD represents a significant challenge for clinicians. In this context, the reported agreement between clinically predicted cases of DDwR and disk displacement without reduction (DDwoR) with MRI findings is noteworthy. The findings suggest that a standardized assessment conducted by a trained examiner is useful in evaluating patients with TMD. Nonetheless, the potential for the overdiagnosis of JE, DDwR and DDwoR on MRI in the absence of clinical symptoms highlights the need for further studies.37

In the study conducted by Koca et al., which also assessed the intensity of pain, the pain score in the group with JE was significantly higher than in the group without JE (p < 0.05).17 The same study suggested that disks with round shapes were more commonly found in patients without JE (p < 0.001), and that folded disk type was more common in patients with JE (p < 0.001).17 Westesson and Brooks found a strong correlation between TMJ pain, disc displacement and JE.16

Multiple studies on MRI of the TMJ11, 16, 17, 38, 39 showed that patients with DDwR have a higher prevalence of JE on MRI scans and clinical pain when compared to patients with a normal disk–condyle relationship. Abnormal mechanical loads on joints with a displaced disk may lead to molecular events that generate free radicals and nitric oxide, thus explaining the presence of joint inflammation and pain.40 Roh et al. demonstrated that joint pain is associated with an increased prevalence and severity of JE in joints affected by DDwR and DDwoR.20 Joint effusion may be related to different inflammatory or non-inflammatory conditions in the TMJ, such as synovitis (p = 0.031) and adherences (p = 0.042), as highlighted by González et al.41 In general, JE is statistically associated with various forms of internal derangement18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 31, 42 and pain.

These findings are consistent with the correlation discovered between JE and pain in other joints, such as the shoulder, the knee and the ankle, as reported by various authors.43, 44, 45, 46, 47

Pain plays a crucial role in the diagnosis and treatment of patients. Its significance cannot be overstated, as it serves as the foundation upon which all medical examinations and treatments are based. It is important to keep this in mind when weighing the benefits of MRI against clinical examination in the diagnosis of TMJ-related pain. Magnetic resonance imaging is a method that requires careful evaluation in relation to the patient’s clinical manifestation in order to avoid overinterpretation. Studies have revealed that even in cases of unilateral clinical symptoms, TMJs of both sides tend to exhibit similar combinations of MRI signs.48, 49 Asymptomatic JE does not require treatment, though this review suggests that it is much more frequently associated with pain than its absence.

The findings of the review indicate that pain experienced during clinical examination can serve as a reliable indicator of JE as observed through MRI. These outcomes bear significant clinical implications, since pain is often the primary reason for patients to seek medical attention and is frequently the foundation upon which clinicians base their therapeutic strategies. Therefore, recognizing the association between pain and JE can facilitate the process of differential diagnosis, leading to more effective outcomes. An extensive clinical assessment that takes into consideration 6 parameters, including pain, has been demonstrated to accurately predict the presence of JE on MRI in 78.7% of cases.7 The clinical examination exhibits a high positive predictive value of 84.3%. In other words, the presence of clinically diagnosed pain is a reliable predictor of the presence of effusion in the TMJ.7 Future studies should be directed toward the search for a more specific association with function-dependent symptoms, which may be influenced in a greater way by the presence of effusion than unspecific TMJ pain.

Future research directions

Despite the evidence presented in this systematic review, which supports a significant association between TMJ effusion and clinical pain, several limitations necessitate further research. One of the primary challenges is the heterogeneity of the included studies, particularly with regard to the methodologies used for pain assessment, imaging techniques and study populations. Future research should prioritize the standardization of these parameters to improve comparability and reproducibility of findings.

It is recommended that future studies employ uniform pain assessment tools that consider both subjective pain experiences and objective functional limitations. The use of standardized MRI protocols, including machine strength (1.5T vs. 3.0T) and imaging sequences, can ensure consistency in detecting effusion and other structural abnormalities.

The current body of literature is primarily composed of cross-sectional studies, which limit the ability to establish causal relationships between TMJ effusion and pain. Prospective, longitudinal studies that track patients over time can offer insight into the progression of JE and its impact on pain. Interventional studies assessing the correlation between the resolution of TMJ effusion and pain reduction could further validate its role as a clinical marker.

Given the evidence that psychological factors may influence TMJ pain perception, future research should incorporate psychological assessments to differentiate between pain of inflammatory origin and pain influenced by psychosocial factors. Biochemical markers of inflammation in TMJ effusion could provide additional objective measures to correlate with MRI findings and clinical symptoms.

A significant number of the reviewed studies exhibited relatively small sample sizes. The implementation of larger, multicenter trials could enhance statistical power and facilitate the acquisition of a more generalizable understanding of the relationship between effusion and pain across diverse populations.

Since TMJ effusion may be more strongly correlated with functional pain rather than with general TMJ discomfort, future research should specifically evaluate pain that is triggered by movement or function.

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) could improve the detection and quantification of effusion on MRI scans. The application of AI-driven pattern recognition holds promise in the prediction of pain severity based on imaging findings.

By addressing these limitations, future studies can refine the clinical relevance of TMJ effusion as a diagnostic and prognostic marker. This approach is expected to enhance patient management by reducing the use of unnecessary imaging and improving targeted therapeutic interventions.

Conclusions

A substantial body of research has identified a significant association between pain and JE. This emphasizes the crucial role of pain in detecting this condition, and highlights the necessity for meticulous evaluation of patients with joint pain to minimize the reliance on costly, second-level diagnostic procedures, such as MRI. Moreover, the presence of TMJ pain in the absence of effusion may be considered quite atypical. Consequently, effusion should be prioritized as the primary factor to consider during pain evaluation to potentially explain function-dependent symptoms. In instances where clinical presentations deviate from the norm, characterized by the lack of association between pain and effusion, the diagnostic process should be directed toward identifying alternative sources of pain.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.