Abstract

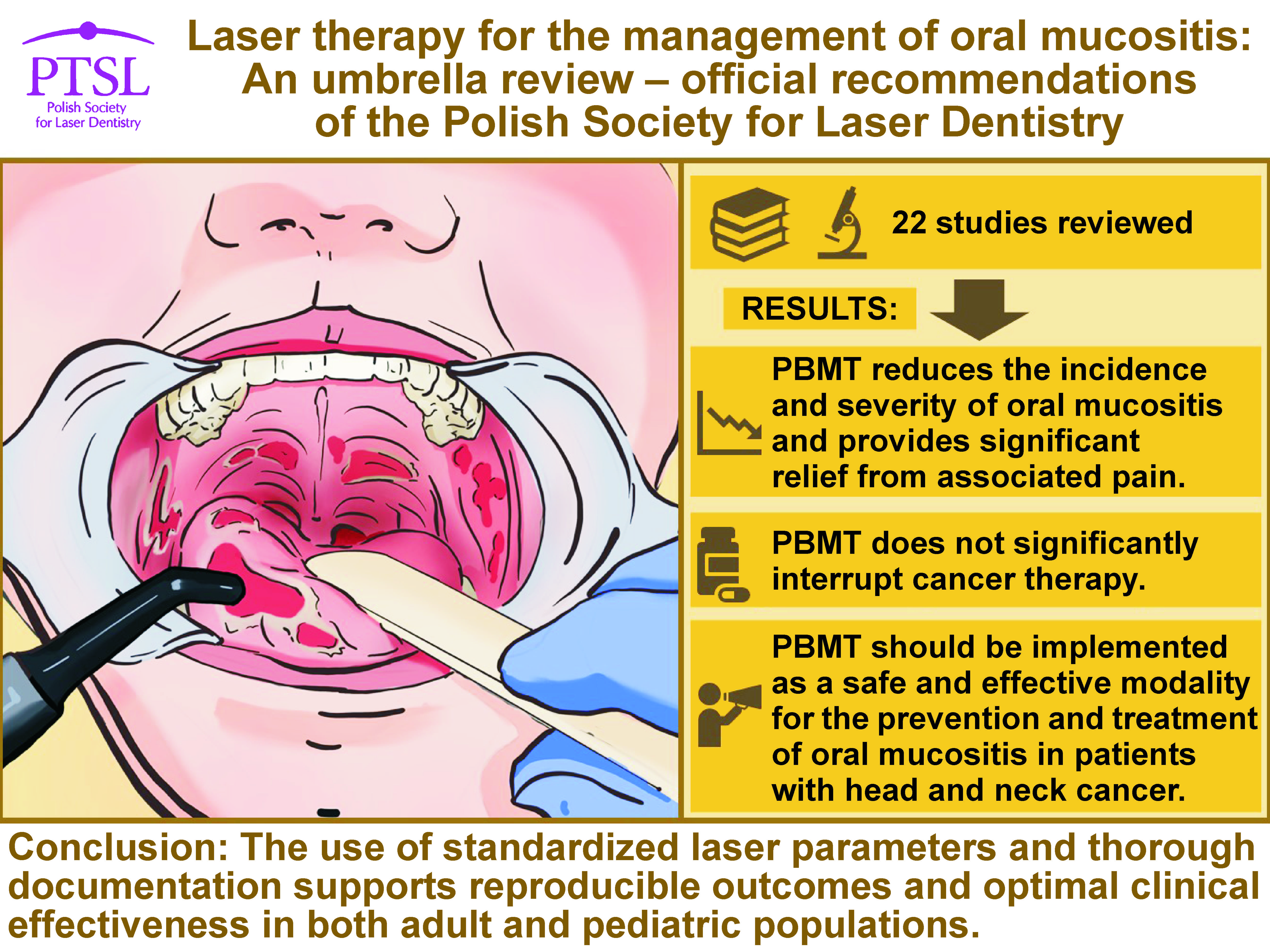

Oral mucositis (OM) is a common and debilitating side effect of cancer therapy that impairs nutrition, increases infection risk, and often disrupts oncologic treatment. Photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) has emerged as an effective, non-invasive method for OM prevention and management.

This umbrella review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology. A comprehensive search of PubMed®/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Cochrane Library identified systematic reviews and meta-analyses on laser therapy for OM published through July 2025. The data extraction process centered on clinical outcomes, laser parameters and safety.

Twenty-two reviews met the inclusion criteria. Photobiomodulation therapy significantly reduced the incidence of OM, disease severity, pain, and healing time across adult and pediatric populations. Preventive PBMT decreased the risk of severe OM (grade 3–4) by 40–80%, while therapeutic PBMT shortened ulcer duration by 4–7 days. The combination of PBMT and photodynamic therapy (PDT) enhanced mucosal healing and alleviated pain. Optimal outcomes were achieved when wavelengths of 630–670 nm (intraoral) and 780–850 nm (extraoral) were used, with fluences of 2–6 J/cm2. No serious adverse events were reported.

Photobiomodulation therapy demonstrates strong efficacy and safety in the management of OM, improving quality of life and treatment continuity in oncology patients. The Polish Society for Laser Dentistry (PTSL) endorses PBMT as a standard supportive care modality, particularly in the context of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and head and neck chemoradiation. Protocol adherence and parameter standardization are essential to ensure the reproducibility and clinical effectiveness of research findings.

Keywords: low-level laser therapy, head and neck cancer, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, cancer therapy, photobiomodulation

Introduction

Rationale

Oral mucositis (OM) represents one of the most debilitating and clinically significant complications of cancer therapy, affecting the oral and gastrointestinal mucosa and carrying potentially life-threatening consequences.1, 2, 3, 4 This inflammatory condition, characterized by erythema, edema and ulceration of the mucous membranes lining the oral cavity, occurs as a direct result of the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy (CT) and radiotherapy (RT) on rapidly dividing epithelial cells.5 The clinical manifestations of OM range from mild discomfort and erythema to severe confluent ulcerations that can prevent oral intake, necessitate narcotic analgesics and require parenteral nutrition.6, 7, 8 The epidemiological burden of OM is substantial and varies significantly based on treatment modality and patient characteristics. Mucositis contributes to prolonged hospitalization, higher infection rates, and delays or reductions in CT. Excluding high-risk cases such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and RT, the incidence of this condition ranges from 5% to 15%. Up to 40% of patients receiving 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), with or without leucovorin, develop OM, with 10–15% of these cases being classified as severe. Irinotecan has been associated with severe gastrointestinal mucositis in over 20% of patients. In bone marrow transplant recipients, OM is reported in 75–85% of cases and is frequently the most severe side effect of the treatment. Melphalan-based regimens are particularly associated with high rates of the condition.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 The clinical and economic impact of OM extends far beyond the immediate discomfort experienced by patients. This condition has a significant influence on quality of life, disrupting normal oral functions such as eating, swallowing and speaking. Furthermore, it has been identified as a portal for potentially life-threatening infections.14 The healthcare burden is considerable, with OM-related complications contributing to increased hospitalization rates, extended length of stay, and substantial healthcare costs.15 Despite the advances in supportive care and increased understanding of the pathophysiology of mucositis, effective prevention and management strategies remain limited.16, 17, 18, 19 The condition involves a complex, multi-phase pathological process including initial tissue injury, inflammatory amplification, ulceration with bacterial colonization, and eventual healing phases. This complexity, in conjunction with the heterogeneity of cancer treatments and patient populations, has rendered the development of universally effective interventions challenging.

Oral mucositis grading scale

The World Health Organization (WHO) scale is a standardized tool used to assess the severity of OM by combining both subjective symptoms and objective clinical findings.19 This grading system ranges from 0 to 4, with grade 0 indicating no signs of OM. Grade 1 is characterized by erythema and soreness without ulceration. Patients with grade 2 OM typically present with ulceration, yet are still able to consume solid foods. Grade 3 involves ulcers severe enough to require a liquid diet due to pain or difficulty chewing and swallowing. Grade 4 is the most severe stage, where extensive ulceration makes oral alimentation impossible. This scale is widely used in clinical and research settings for the evaluation of treatment effects and the guidance of patient care.19

Objectives

The aim of this umbrella review was to systematically collect, evaluate and synthesize the highest level of existing evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the use of laser therapy for the prevention and management of OM in cancer patients. Specifically, the review sought to assess the clinical effectiveness of various laser modalities in reducing the incidence, severity, duration, and pain associated with mucositis, and to evaluate the consistency of findings across different patient populations and treatment protocols. By consolidating current evidence, the study intends to inform clinical guidelines and support evidence-based recommendations by the Polish Society for Laser Dentistry (PTSL).

Material and methods

This study was carried out in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework for umbrella reviews and was registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD420251119913).20

PICO question

The following PICO question was formulated: In patients experiencing or at risk of OM (Population), does laser therapy (Intervention), as compared to standard care or no laser treatment (Comparison), lead to improved clinical outcomes such as reduced severity, duration or pain (Outcome)?21

Search strategy

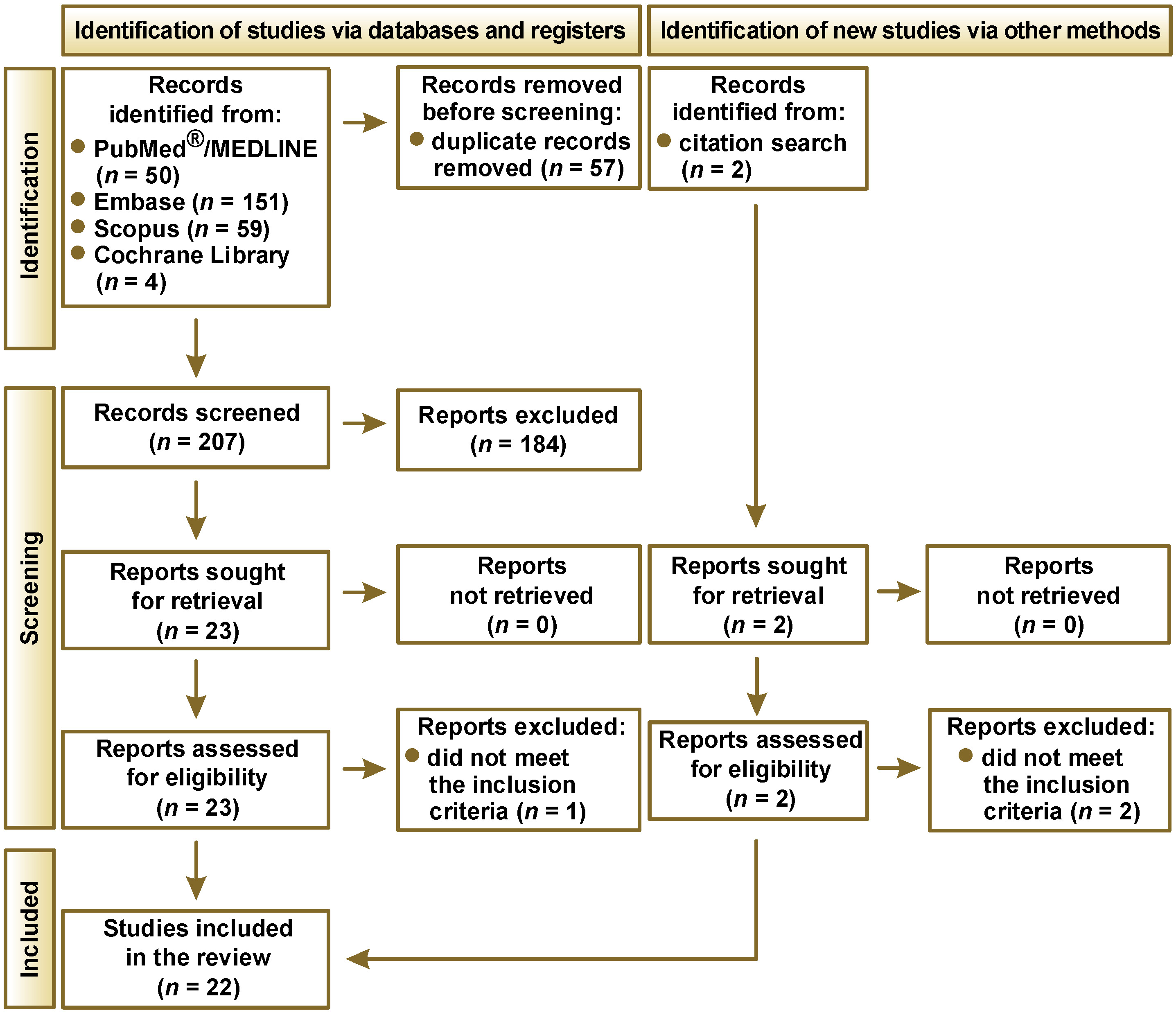

This umbrella review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines to ensure transparency and methodological rigor.22 A systematic and comprehensive search of several major electronic databases, including PubMed®/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Cochrane Library, was conducted in July 2025 to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating the use of laser therapy in the prevention or management of OM. Three independent reviewers performed the literature search using a carefully constructed combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords related to OM and laser treatment. Studies published in English up to July 1, 2025, were included. The two-phase screening process involved an initial screening of titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text assessment by 3 independent reviewers using clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. In order to ensure that the work is complete, the reference lists of all included reviews were examined manually to find additional relevant studies. The search strategies aimed to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses that examined the effectiveness of laser-based interventions in the prevention and management of OM. The queries targeted literature published between 2020 and 2025, drawn from major biomedical databases (Table 1).

Study selection

The study selection process began with an initial review of titles and abstracts, guided by well-defined eligibility criteria that were tailored to the research objectives. Disagreements between the reviewers at this stage were resolved through collaborative discussion. This umbrella review targeted systematic reviews and meta-analyses that investigated the use of laser-based therapies and related approaches for the management or prevention of OM. Only studies assessing clinically relevant outcomes such as symptom severity, duration, pain level, or mucosal healing were considered for inclusion. To ensure data reliability, the inclusion criteria were limited to peer-reviewed reviews that employed clear methodology, provided comparison groups, and reported quantifiable health outcomes. Reviews were excluded in the absence of peer review, the presence of opinion-based content (e.g., editorials or narrative summaries), or if they were published only as conference abstracts or unpublished theses. Articles not written in English, which lack sufficient detail on intervention protocols, and which do not focus directly on laser interventions for OM, were also omitted. Studies that failed to differentiate between laser therapy or lacked clinical relevance were excluded from the analysis, as were duplicates and secondary reports from the same dataset, unless they offered new findings.

The PRISMA flow diagram, illustrating the study selection process for the systematic review, is presented in Figure 1. The database search yielded a total of 264 records: 50 from PubMed®/MEDLINE; 151 from Embase; 59 from Scopus; and 4 from the Cochrane Library. An additional 2 records were identified through citation search. Prior to the screening process, 57 duplicate records were removed. Of the remaining 207 papers, 184 were excluded, and 23 reports were sought for retrieval. A total of 23 reports were successfully retrieved and assessed for eligibility. One report was excluded as it did not meet the criteria for being a systematic review or a meta-analysis. Ultimately, 22 studies were included in the review.

Data extraction

Once the final set of eligible reviews was established, 3 reviewers independently extracted data using a standardized protocol designed to ensure consistency and minimize bias. Key information collected from each included review comprised the first author, the year of publication, the review type (systematic review or meta-analysis), the clinical context, and characteristics of the studied population. Particular attention was given to the details regarding the photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT)/low-level laser therapy (LLLT) or laser therapy protocols, encompassing the type of laser or light source used, wavelength, power output, energy density, application technique, and treatment duration. Where available, information on the frequency of treatment, its timing relative to CT or RT, and whether laser therapy was used preventively or therapeutically was also extracted. Data on primary and secondary outcomes, such as mucositis severity, duration, pain relief, and impact on quality of life, was recorded to facilitate a comparative analysis across studies and to evaluate the consistency and clinical relevance of reported effects.

Assessment of the risk of bias and study quality

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed independently by 3 reviewers using a customized risk-of-bias assessment tool adapted for the evaluation of systematic reviews on therapeutic interventions. The tool covered 9 domains designed to capture both reporting quality and internal validity. The assessment criteria encompassed the following:

– clear identification and description of the laser modality used, including treatment parameters where applicable;

– defined intervention protocols, such as treatment frequency and adjunctive care;

– specification of relevant clinical outcomes;

– inclusion of appropriate comparator groups;

– transparent criteria for study inclusion, including population characteristics;

– assessment of bias control measures, including blinding where feasible;

– appropriateness and transparency of statistical methods used;

– full disclosure and clarity in the reporting of outcomes, including adverse events and follow-up data;

– reporting of funding sources and potential conflicts of interest.

Each domain was scored using a binary system (1 for criterion met, 0 for unmet), yielding a total score between 0 and 9. The reviews were classified as having low (7–9 points), moderate (4–6 points) or high (0–3 points) risk of bias. Disagreements in scoring were resolved through reviewer discussion, with consultation from a fourth reviewer in cases of unresolved conflict. The quality appraisal process was conducted in accordance with the best-practice guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.23

Results

Results of the risk of bias and quality assessment

The initial screening of titles and abstracts was conducted independently by 3 reviewers to promote objectivity and reduce the risk of selection bias. Agreement among reviewers was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient to quantify the level of consistency across assessments. When discrepancies in the study inclusion arose, they were resolved through structured consensus meetings to ensure transparency and consistency in the selection process. This multi-reviewer approach was adopted to enhance the methodological rigor of the umbrella review and to ensure that only systematic reviews and meta-analyses, specifically those evaluating laser therapy for OM, were included.24

As summarized in Table 2, all but one study were judged to be at low risk of bias. Importantly, no studies were excluded on the basis of their risk-of-bias rating alone.

Characteristics of the included reviews

Multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy of laser-based interventions, particularly PBMT, in reducing the severity and pain associated with OM in patients with head and neck cancer, especially in pediatric populations.25, 26, 27, 28 Alqahtani and Khan elucidated that a combination of oral care, glutamine, vitamin E, biological agents, and laser therapy effectively alleviated the symptoms of OM in children, with PBMT exhibiting a consistent reduction in pain and severity of the condition.25, 26 Braguês et al. noted the preventive effects of interventions such as PBMT, palifermin, honey, and zinc, however, they emphasized the absence of standardized protocols.27 A study by Calarga et al. confirmed the safety and effectiveness of PBMT, although preventive outcomes varied and the absence of established protocols underscored the need for standardization.28 Campos et al. found that PBMT not only reduced OM severity but was also cost-effective in patients with head and neck cancer.29 Cronshaw et al. emphasized that optical parameters, particularly spot size and energy delivery, critically influence PBMT outcomes.30, 31 The authors recommended the implementation of individualized dosing based on tissue depth and the patient.30, 31 Cruz et al. reported that PBMT significantly reduced OM severity, though the heterogeneity of outcomes precluded a meta-analysis on pain or lesion duration.32 A study by de Oliveira et al. found that combining photodynamic therapy (PDT) with PBMT led to a significant acceleration in mucosal healing compared to PBMT alone.33 De Sales et al. linked PBMT to a reduction in OM incidence and inflammation through cytokine modulation and enhanced antioxidant activity.34 Dipalma et al. echoed these findings, showing that PBMT has an impact on cytokines and keratinocyte differentiation.35 This suggests that its mechanism is driven by the modulation of inflammation and oxidative stress.35 Franco et al. concluded that laser therapy significantly reduces OM severity, especially in patients undergoing transplantation or chemoradiation.36 Joseph et al. showed that PDT combined with PBMT offered greater pain and symptom relief in comparison to PBMT alone, with meta-analysis supporting superior efficacy.37 Another study by Joseph et al. explored the potential of light-emitting diode (LED)-based therapy, which showed promise in symptom control despite limited evidence and variability across studies.38 Khalil et al. found that PBMT using 660-nm aluminium gallium indium phosphide (InGaAlP) lasers led to a consistent reduction in OM severity, with IL-6 levels demonstrating the strongest correlation with the intensity of mucositis.39 Lai et al. reported that cryotherapy combined with PBMT was more effective than either intervention alone in reducing severe OM; however, no significant differences were observed for moderate OM.40 Parra-Rojas et al. reported that prophylactic PBMT effectively prevented OM, with red light used intraorally and infrared extraorally, but emphasized the need for protocol standardization.41 Peng et al. confirmed the enhanced effect of cryotherapy + PBMT, both outperforming usual care, especially in severe OM cases.42 Potrich et al. also supported this synergy and emphasized the efficacy of both modalities individually.43 Redman et al. found that while PBMT may benefit children with CT-induced OM, results were inconsistent and further trials are needed.44 Sánchez-Martos et al. highlighted the ability of PBMT to decrease severe OM incidence and duration, reduce pain, and improve quality of life across various assessment tools.45 Finally, Shen et al. confirmed the broad efficacy of PBMT, particularly in pediatric patients, and reinforced its safety profile, emphasizing the importance of standardized treatment protocols.46 Table 3 and Table 4 summarize this data.

Discussion

Background

Over the past 3 decades, photobiomodulation, now more precisely termed photobiomodulation therapy, has evolved from an intriguing laboratory observation to a modality incorporated into multiple international guidelines. The ensuing discourse synthesizes mechanistic insights, preclinical evidence, data from clinical trials, guideline positions, and implementation challenges, providing a panoramic view of the role of PBMT in the prevention and management of OM.47, 48, 49, 50, 51 Radiotherapy, CT and high-dose conditioning regimens trigger a five-phase pathobiological cascade encompassing initiation, primary damage response, signal amplification, ulceration, and healing.52 Reactive oxygen species and DNA strand breaks ignite necrosis factor kappa B (NF-κB)-mediated transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines, notably tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6, which drive apoptotic loss of the basal epithelium and submucosal injury.53, 54 Secondary bacterial invasion further amplifies tissue damage, prolonging ulcerative phases and raising the risk of sepsis in neutropenic hosts.55 Understanding these molecular checkpoints is critical, as PBMT targets several of the same signaling nodes, offering a biologically plausible strategy for interrupting OM evolution.52, 53, 54

Rationale for photobiomodulation therapy

Photobiomodulation therapy involves the delivery of photons (400–1100 nm) at low power (5–200 mW), which are primarily absorbed by mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase.55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62 From a photophysical perspective, blue photons possess higher quantum energy than red photons, a parameter that plays a fundamental role in determining the nature and efficiency of electromagnetic radiation interactions with biological matter. Blue (400–500 nm), red (620–750 nm) and near-infrared (750–1100 nm) light each exhibit distinct mechanisms of action in PBMT, reflecting differences in wavelength and tissue penetration depth. Blue light acts superficially (up to about 1 mm) and primarily exerts antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects by generating reactive oxygen species, which damage microbial cell membranes and modulate immune responses. Red light penetrates deeper (several millimeters) and activates mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase, enhancing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, reducing oxidative stress, and stimulating tissue repair, angiogenesis and wound healing.57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62 Near-infrared light reaches the greatest depths (up to several centimeters), affecting muscles and bones by activating cytochrome c oxidase, improving microcirculation, reducing inflammation, and promoting deep tissue regeneration. These differences guide clinical applications: blue light is used for superficial infections and inflammation; red light for soft tissue healing and pain reduction; and near-infrared light for musculoskeletal pain and deep tissue repair.55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62

The biological mechanisms and cellular effects triggered by PBMT include transient displacement of mitochondrial nitric oxide, which enhances oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis.63 Modulation of reactive oxygen species within a therapeutic window activates redox-sensitive transcription factors such as nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) without inducing oxidative stress.64 The upregulation of growth factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) as well as increased collagen synthesis promote re-epithelialization.65 The reduction of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α in both saliva and serum, with levels correlating to mucositis severity scores, has also been observed.39 Together, these actions produce analgesia, suppress inflammation, and accelerate wound healing, key outcomes in effective OM management. Studies on rodent models consistently show that PBMT administered at wavelengths of 660–810 nm and fluences of 2–6 J/cm2 leads to smaller ulcers, faster epithelial regeneration, and reduced local TNF-α expression.66, 67, 68 While animal studies employ standardized dosing conditions that do not fully reflect clinical variability, they serve to reinforce the mechanistic basis for PBMT and guide the selection of wavelength and fluence parameters in human trials.

Distinction between PBMT, PDT and combined applications

It is important to differentiate PBMT from PDT, as they differ in both mechanism of action and clinical application. Photobiomodulation involves the direct stimulation of tissue using low-level, non-ionizing radiation (typically in the red or near-infrared spectrum) and does not require a photosensitizing agent. The primary effects of PBMT include modulation of inflammation, enhancement of cellular repair, and acceleration of wound healing through mitochondrial and redox pathways.69, 70 In contrast, PDT requires the administration of a photosensitizer, which is subsequently activated by a specific wavelength of light. This activation leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species, resulting in selective cytotoxicity and tissue destruction, which is often used for antimicrobial or antitumor purposes.69, 70 While the mechanisms are distinct, several systematic reviews have noted that combining PDT with PBMT may provide added therapeutic benefits for patients with OM. For instance, de Oliveira et al. discovered that this combination resulted in significantly faster mucosal healing compared to the administration of PBMT alone.33 Similarly, Joseph et al. reported that dual therapy produced greater reductions in pain and symptom duration than PBMT monotherapy.37 These findings suggest that integrated protocols, leveraging the complementary actions of PDT and PBMT, may represent a promising direction for future management of mucositis. Nevertheless, further research is needed to optimize dosing and patient selection.71

Impact on quality of life

In addition to a reduction in the clinical severity and duration of OM, PBMT delivers consistent and measurable improvements to patient quality of life. This outcome has been documented in studies using validated instruments, including the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire (UW-QoL), and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT).29, 43, 45 Photobiomodulation therapy supports key functional domains. After PBMT, patients report an improvement in their ability to eat, speak and perform daily activities. Preserved oral function contributes to improved nutritional status and a reduced risk of malnutrition. The alleviation in pain enables more restful sleep and facilitates social interaction and emotional stability. In controlled trials, PBMT-treated patients demonstrated significantly higher quality of life scores at the conclusion of treatment. For example, one study found UW-QoL scores of 687 for PBMT patients vs. 607 for placebo on day 35, with social-emotional scores also notably higher (408 vs. 348, p = 0.003).45, 72 These improvements translate to better psychological resilience, less disruption of cancer therapy, and reduced hospitalizations, underscoring the value of PBMT as a standard component of supportive oncology.

Impact on pain

Photobiomodulation has been shown to significantly reduce pain associated with OM in cancer patients, offering both preventive and therapeutic benefits. The included studies consistently report that PBMT reduces pain intensity, shortens lesion duration, and decreases the need for systemic analgesics, including opioids, particularly in patients undergoing head and neck chemoradiotherapy or HSCT.28, 29, 36, 45, 46, 65 The analgesic effects of the treatment are attributed to the modulation of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, stimulation of tissue repair, and improved microcirculation.34, 35, 39 In clinical trials, PBMT-treated patients experienced up to a 50% reduction in mean pain scores compared with controls, enabling improved oral function, nutritional intake and quality of life.45, 65 Owing to its strong safety profile and non-invasiveness, the therapy is recommended as a standard supportive care intervention in international guidelines.63, 64

Age-specific considerations and treatment protocols

The management of OM with laser therapy requires careful consideration of age-specific factors, as different patient populations present unique challenges and may respond differently to PBMT.44, 73 Evidence reveals significant variations in efficacy, tolerability and optimal protocols across age groups. In the case of very young children (3–6 years), the available data remains limited but promising, with cooperation being a key challenge.73 For this age group, extraoral PBMT is often preferable to intraoral applications in order to minimize discomfort and reduce the need for active cooperation, with shorter session durations being recommended.73 School-age children (7–12 years) have the strongest pediatric evidence base, with multiple systematic reviews confirming the efficacy of PBMT in this age group. A meta-analysis showed that prophylactic PBMT significantly reduced the odds ratio (OR) for developing OM (OR = 0.50; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.29–0.87; p = 0.01) and severe mucositis (OR = 0.30; 95% CI: 0.10–0.90; p = 0.03).74 School-age children generally cooperate well during intraoral applications under proper supervision, and standard protocols with 10–15-min sessions are well tolerated.75 Adolescents and young adults (13–18 years) show excellent compliance and achieve outcomes similar to adults, with studies consistently reporting reduced severity and duration of mucositis. Photobiomodulation is considered an effective method for the treatment of OM in young cancer patients due to its analgesic, anti-inflammatory and healing properties.76

Adults represent the most extensively studied population for laser therapy in OM, with the strongest evidence base. The Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) and the International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO) have established guidelines recommending the use of 660-nm wavelength, a power density of 417 mW/cm2, and an energy density of 4.2 J/cm2 for patients receiving a combination of CT and RT.63, 77, 78 In patients after HSCT, protocols using 660 nm with 2–4 J/cm2 have been shown to result in a significant reduction in the incidence of severe mucositis. Elderly patients (>65 years) also benefit from laser therapy, with studies showing reductions in mucositis severity and duration, as well as a decrease in weight loss and lower morphine requirements. However, for this age group, slightly shorter sessions (10–20 min) and energy densities of 2–6 J/cm2 with careful monitoring are advised.79 Patients who had undergone HSCT, particularly adults, exhibit the most robust data, with meta-analyses showing significant reductions in the severity of mucositis. Pediatric HSCT patients demonstrate similar benefits, but modifications in session duration and technique are required.80 For 5-FU-induced mucositis, limited age-specific data exists. The utilization of animal models has indicated that 660 nm and 6 J/cm2 represent the optimal parameters.81, 82 Pediatric patients with methotrexate-induced mucositis respond particularly well to the treatment, with the incidence reduced from 66.67% to 6.67%.73 Across all age groups, the optimal wavelengths range from 660 nm to 670 nm, with energy density and session length tailored to age, cooperation level and physiology: extraoral and brief sessions for very young children; supervised intraoral applications for school-age children; adult protocols for adolescents; standard intraoral treatment for adults; and modified positioning for elderly patients.44 The safety profiles are favorable across all groups. A total of 2,700 patients were included in the analyzed studies, and minor, infrequent adverse events were observed. The majority of these events were associated with cooperation rather than device function. However, very young children may require sedation, while elderly patients may need the assessment for oral anatomy changes. Furthermore, all patients require eye protection during treatment.44 Photobiomodulation protocols for edentulous individuals should ensure full coverage of the alveolar ridges and vestibular mucosa, as these areas are prone to mucositis-related ulceration and discomfort despite the absence of teeth. Moreover, proper adaptation of applicator angulation is essential to maintain consistent energy delivery.80, 81, 82

The implementation of laser therapy for OM patients should be guided by age-appropriate protocols, supported by targeted training that addresses developmental considerations and cooperation strategies. While current evidence supports the use of PBMT across all age groups, significant gaps remain, particularly with regard to very young children and elderly patients. Priority research areas include standardizing pediatric protocols across developmental stages, collecting long-term pediatric safety data, defining optimal approaches for elderly patients with comorbidities, clarifying age-dependent dose–response relationships, and developing strategies to enhance cooperation in young children. Acknowledging that a one-size-fits-all approach is not optimal, clinicians should tailor treatment to age-specific needs while promoting further research to refine these protocols.44, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82

Xerostomia

The administration of daily PBMT with well-defined parameters reduces short-term OM symptoms in elderly patients and improves salivary gland function. Oliveira et al. have demonstrated an increased salivary flow and protective potential of PBMT in the management of xerostomia.83, 84 Photobiomodulation acts by stimulating cytochrome c oxidase, activating cellular signaling pathways, increasing ATP production, enhancing metabolism, and providing anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects. Clinical trials have demonstrated that daily protocols of 810 nm at 6 J/cm2 or 660 nm at 4 J/cm2 result in a greater reduction in mucositis severity, pain and oral discomfort than every-other-day therapy. These findings are accompanied by an increased unstimulated and stimulated salivary flow, reduced xerostomia-related discomfort, and improved oral health-related quality of life by up to 52%, with effects that persist for up to one year.83, 84, 85, 86, 87 These improvements in mucositis symptoms may be enhanced by positive effects on salivary gland function.87 The standard protocol outlined by Ferrandez-Pujante et al. involves 6 weekly sessions over a period of 6 weeks, with extraoral application over the salivary glands at 810 nm and 6 J/cm2 using a GaAlAs diode, with a duration of 2 min 24 s for the parotid gland and 1 min 12 s for the submandibular gland.88 Lončar et al. describe an intensive protocol of 10 consecutive daily sessions applying PBMT parameters of 904 nm at 246 mW/cm2 and 29.5 J/cm2 for 120 s per area, both extraorally and intraorally at sublingual glands.89, 90 Clinical studies in older adults have reported an increased unstimulated and stimulated salivary flow, reduced subjective oral dryness, and a 52% improvement in oral health-related quality of life.89, 90 These therapeutic effects were maintained for up to 1 year.88, 89 The benefits have been linked to the regeneration of salivary gland cells, improved microcirculation, increased salivary immunoglobulin A, and reduced oxidative stress.87, 90, 91 A meta-analysis conducted by Oliveira et al. confirmed these effects, identifying optimal parameters as wavelengths of 790–830 nm, power of 30–120 mW, energy density below 30 J/cm2, and 2 to 3 weekly sessions.83 Significant increases were noted in stimulated salivary flow (mean difference (MD) = 2.90; 95% CI: 1.96–3.84), and reductions were observed in xerostomia-related pain (MD = −3.02; 95% CI: −5.56–−0.48). Furthermore, an enhancement in the quality of life was documented.83, 92 Benefits extend to elderly patients suffering from post-RT hyposalivation.88, 89, 90, 91, 92

Clinical applications

Preventive PBMT, when initiated on the first day of chemoradiation or conditioning, reduces the incidence of grade 3–4 OM by approx. 40–80% compared with sham treatment or standard oral care.65, 93, 94 Therapeutic PBMT, applied at the onset of OM, shortens ulcer duration by 4–7 days and reduces mean pain scores by half on validated assessment scales.95, 96 Patients receiving PBMT also require substantially less systemic opioid use, highlighting its analgesic benefit.65, 97 In the HSCT setting, low-power 660-nm diode lasers (4 J/cm2 intraorally) have reduced the incidence of severe OM from 66.67% to 6.67% in pediatric patients, demonstrating notable efficacy even in profoundly myelosuppressed hosts.96 A meta-analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials in adults undergoing myeloablative transplants reported a standardized MD of −1.34 (95% CI: −1.98–−0.98) for severe OM, favoring PBMT.36, 95 In head and neck RT, a landmark French multicenter trial demonstrated that a daily 632.8-nm helium–neon (He–Ne) laser treatment (2 J/cm2 prophylactic; 4 J/cm2 therapeutic) during concurrent chemoradiotherapy reduced grade 3–4 OM incidence to 6.4% compared with 48% in the placebo group, and decreased gastrostomy placement rates and unplanned treatment interruptions.65 Follow-up studies using 650-nm LED arrays and 850-nm extraoral panels have replicated these outcomes while improving clinical workflow.95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100 Among patients receiving solid tumor CT, particularly 5-FU-based regimens, results varied but generally demonstrated a relative risk reduction of 23–28% in severe OM during weeks 3–4 of treatment, likely due to shorter duration of PBMT and non-standardized energy delivery.93, 100, 101

Possile confounding factors

When interpreting the findings of this umbrella review, it is important to recognize the potential influence of confounding factors that may have affected the reported efficacy of PBMT for OM. Variations in cancer type, disease stage and oncologic regimens (including CT agents, RT dose and field, and conditioning protocols for HSCT) can substantially alter OM risk and severity, thereby influencing the apparent benefit of PBMT. Patient-related factors, such as age, sex, comorbidities, nutritional status, and baseline oral health, also represent important sources of variability.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Furthermore, concomitant supportive care interventions, including mouth rinses, cryotherapy or pharmacologic agents, may act synergistically or independently to reduce OM severity, making it difficult to isolate the effect of PBMT. The technical heterogeneity in laser parameters, such as wavelength, fluence, power density, application technique, frequency, and intraoral vs. extraoral delivery, further complicates the comparison of results across studies. Differences in operator experience, treatment setting and adherence to standardized protocols add an additional layer of complexity. The presence of these confounders, whether individually or in combination, has the potential to introduce bias into effect estimates. Consequently, it is essential to consider these confounders when interpreting the results of pooled studies and formulating clinical recommendations.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46

International guidelines and consensus positions

International bodies have progressively upgraded PBMT recommendations (Table 5). The 2020 MASCC/ISOO guidelines categorize intraoral PBMT as level I (strong) for the prevention of OM in HSCT and head and neck RT, contingent on adherence to validated protocols.63 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Interventional Procedures Guidance 615 (IPG615) found “adequate efficacy and no major safety concerns,” supporting the adoption of PBMT in UK centers with governance oversight.102 The World Association for Photobiomodulation Therapy (WALT) 2022 position paper extends PBMT to additional indications such as radiodermatitis and lymphedema, stipulating explicit dosimetry ranges.64 The 2022 Health Technology Wales (HTW) appraisal (EAR044) supported PBMT implementation across the Welsh National Health Service (NHS), emphasizing the importance of clinician training and service evaluation.103

According to Parker et al., the complete and precise documentation of all laser operating parameters is a fundamental prerequisite for the reproducibility and scientific validity of laser–tissue interaction studies.104 The authors emphasize that the reporting of only basic information such as output power or wavelength is insufficient. Instead, a comprehensive set of parameters should be included, such as the total energy delivered [J], energy density (fluence) [J/cm2], power density (irradiance) [W/cm2], irradiation time [s], pulse repetition rate [Hz], beam diameter at the target [cm], mode of application (contact or non-contact), beam divergence angle [°], emission mode (continuous wave, pulsed), number and frequency of treatment sessions, and distance from the tip to the tissue. The omission of these variables not only compromises clinical reproducibility but also increases the risk of thermal side effects or treatment failure.80 While no universal gold standard exists, multiple positive randomized controlled trials converge on the use of red (630–680 nm) or near-infrared (780–850 nm) light, with prophylactic fluence around 2 J/cm2 and therapeutic doses of 4–6 J/cm2, typically applied daily or on alternate days.64, 65 Extraoral panels offer ergonomic advantages but require a longer exposure time of approx. 15 min to overcome cutaneous attenuation.99 Effective PBMT covers the lips, buccal mucosae, ventral tongue, floor of mouth, and soft palate, administered in a grid of 1-cm2 points. A review of studies involving over 1,000 patients has revealed no association between PBMT and carcinogenicity, tumor promotion, or serious adverse events, with only mild, transient sensations such as warmth or a metallic taste occasionally reported.65 However, it should be noted that there are several limitations in the current evidence base. Parameter heterogeneity, such as inconsistent wavelengths, energy densities and treatment grids, compromises the comparability of meta-analyses. Blinding presents a challenge, because patients may perceive active treatments as different to sham treatments, potentially resulting in biased subjective pain outcomes. While robust data exists for adult HSCT populations, pediatric dosing, particularly in infants and toddlers, is still largely empirical.19, 105, 106, 107, 108 Future research should focus on precision dosimetry using real-time optical feedback and Monte Carlo-guided fluence planning to tailor therapy to individual mucosal thickness and pigmentation. Furthermore, studies should explore synergistic PBMT combinations with agents like benzydamine or probiotic lozenges for broader mucosal protection, investigate biomarker-guided timing based on salivary cytokine thresholds such as IL-6, and develop automated extraoral LED devices, like wearable neck collars, for home-based PBMT prophylaxis during chemoradiation.101 Photobiomodulation has transitioned from experimental therapy to evidence-based standard of care for high-risk OM populations. Its multimodal benefits, including analgesia, anti-inflammation and epithelial repair, address the full spectrum of OM pathobiology with minimal toxicity. In order to realize the full clinical and economic potential of PBMT, there is a necessity for adherence to validated dosimetry parameters and integration into multidisciplinary supportive care pathways. Further harmonization of protocols, expansion into pediatric and immunotherapy cohorts, and monitoring of long-term oncologic outcomes will serve to consolidate the essential role of PBMT in the management of mucositis.104, 105, 106, 107, 108

The international consensus documents provide precise parameters for PBMT, namely wavelength, power density, fluence, timing, and field mapping, for the purposes of OM prevention and treatment (Table 6, Table 7, Table 8). The application of these validated settings is critical, and deviating from them markedly reduces treatment efficacy.

MASCC/ISOO 2020 guidelines – dose

In the MASCC/ISOO 2020 guidelines,63 evidence-based protocols are linked to the specific oncologic treatment settings (Table 6). Each row represents a complete, validated regiment, and the listed parameters should not be interchanged across protocols.

WALT position paper 2022 – consensus operating windows

In the 2022 WALT position paper,64 the available evidence is synthesized into 2 pragmatic device classes. Photon fluence is expressed in Einsteins [E] (1 E ≈ 4.8 pJ/m2 at 810 nm) (Table 7).

NICE IPG615 2018 – service-level guidance

Although NICE does not mandate particular dosimetry settings, IPG615 outlines the procedural standards that must guide the clinical use of PBMT within the UK healthcare system (Table 8).102

Long-term safety of PBMT

Long-term safety data for PBMT in treating OM in cancer patients demonstrate that PBMT is safe when applied in accordance with the current clinical guidelines. There is no evidence to suggest that PBMT increases the risk of secondary malignancies or tumor recurrence in the oral cavity.109, 110, 111, 112 A 15-year retrospective study in HSCT patients found no immediate or late adverse effects, including no secondary oral cancers linked to PBMT protocols for OM management.109 Similarly, a systematic review of PBMT use for cancer therapy-related toxicities, including OM, reported no tumor safety concerns or significant side effects attributable to PBMT.110 Prospective and retrospective clinical trials in head and neck cancer and HSCT consistently show excellent safety and tolerability, with no device-related adverse events observed across hundreds of treatment sessions.111, 112 These studies confirm the absence of both acute and chronic adverse effects, reinforcing a favorable long-term safety profile of PBMT. According to the WALT guidelines, PBMT should not be applied directly over active tumor sites, despite the absence of evidence indicating tumor promotion.64 While PBMT effectively reduces the severity and pain associated with OM, further research is needed to standardize dosimetry and treatment protocols. The current body of evidence supports the continued use of PBMT for OM in cancer patients without identified long-term safety concerns.104, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120

Future directions

Future perspectives in PBMT highlight the need for further research to refine and expand its clinical applications. Emerging studies emphasize clarifying the precise cellular and molecular mechanisms by which PBMT modulates biological processes, including mitochondrial function, redox signaling and gene expression. The integration of real-time monitoring with artificial intelligence has the potential to optimize dosing in accordance with the individual characteristics of each patient’s tissue. Additionally, advances in technology that combine PBMT with nanomaterials and biomaterials hold the potential to enhance targeting and therapeutic outcomes. The standardization of clinical protocols through rigorous trials remains essential to ensure reproducibility, efficacy and safety across diverse patient groups.

Conclusions

This umbrella review consolidates robust evidence demonstrating that PBMT is a clinically effective and safe approach for the prevention and treatment of OM across various oncologic settings. Supported by findings from 22 high-quality systematic reviews and according to the international guidelines (MASCC/ISOO, WALT, NICE), PBMT significantly reduces the incidence, severity, pain, and duration of OM, while concomitantly improving patients’ quality of life. Furthermore, it facilitates uninterrupted cancer therapy by minimizing treatment-related complications. The Polish Society for Laser Dentistry strongly endorses PBMT as a standard component of supportive care for high-risk patients, especially those undergoing HSCT or head and neck chemoradiotherapy. Preventive PBMT protocols should be initiated before or at the beginning of therapy using validated dosimetry parameters. In order to ensure both the efficacy and reproducibility of treatment, it is imperative to adhere to the established technical standards. Future efforts should focus on harmonizing pediatric protocols, improving access to PBMT in clinical practice, and advancing research into optimized delivery, biomarker-guided timing and combination therapies. Photobiomodulation constitutes a transformative, evidence-based solution that addresses a critical gap in oncology supportive care, with clear benefits for patients and healthcare systems alike.

Consensus-based clinical guidance from the Polish Society for Laser Dentistry

Based on the synthesis of 22 high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as well as in alignment with the international guidelines (MASCC/ISOO, WALT, NICE), the PTSL endorses the use of PBMT as a safe and effective modality for the prevention and treatment of OM in patients with head and neck cancer. This recommendation applies to both adult and pediatric populations. However, in very young children or patients who cannot tolerate intraoral application, extraoral (near-infrared) protocols are preferred.

Key clinical recommendations:

– PBMT should be incorporated as standard supportive care for patients receiving high-risk cancer therapies, including HSCT and head and neck chemoradiation;

– Preventive PBMT, initiated before or on the first day of oncologic therapy, significantly reduces the incidence and severity of OM and should be prioritized;

– Implementation should be coordinated with the treating oncologist, who serves as the main clinician overseeing the patient’s oncologic management;

– Therapeutic PBMT, applied after the onset of mucositis, offers clinically meaningful analgesia and accelerates healing;

– Recommended parameters include: wavelengths of 630–670 nm (intraoral) and 780–850 nm (extraoral); fluence of 2–6 J/cm2; and frequency of 3–4 times/week or daily throughout the treatment course (Table 9, Table 10);

– Treatment should cover both intraoral and extraoral sites, including the lips, buccal mucosa, ventral tongue, floor of the mouth, and soft palate. In acute cases, the protocol should be extended to regional lymph nodes to address lymphatic congestion and reduce inflammation.

Photobiomodulation protocols must strictly follow validated dosimetry guidelines to ensure reproducibility and clinical benefits. Deviations from evidence-based parameters markedly reduce treatment efficacy. While the safety profile is excellent, standardized training and documentation are essential for clinical integration. Further efforts should be made to harmonize the use of PBMT in pediatric settings and to explore its cost-effectiveness across various healthcare systems.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.