Abstract

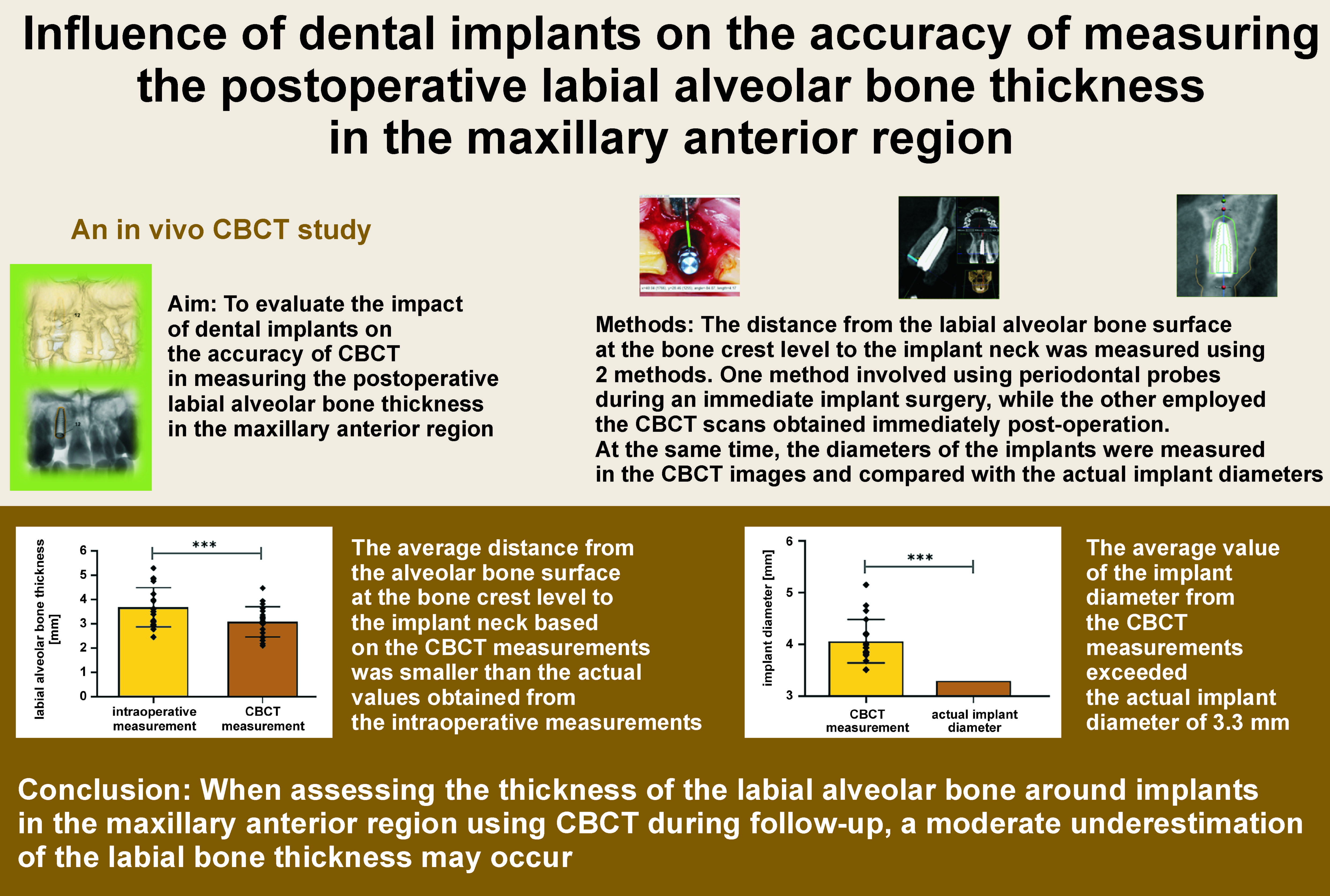

Background. The accuracy of cone-beam computer tomography (CBCT) in measuring the labial alveolar bone thickness requires further evaluation.

Objectives. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the impact of dental implants on the accuracy of CBCT in measuring the postoperative labial alveolar bone thickness in the maxillary anterior region.

Material and methods. The distance from the labial alveolar bone surface at the bone crest level to the implant neck was measured using 2 methods. One method involved using periodontal probes during an immediate implant surgery, while the other employed the CBCT scans obtained immediately post-operation.

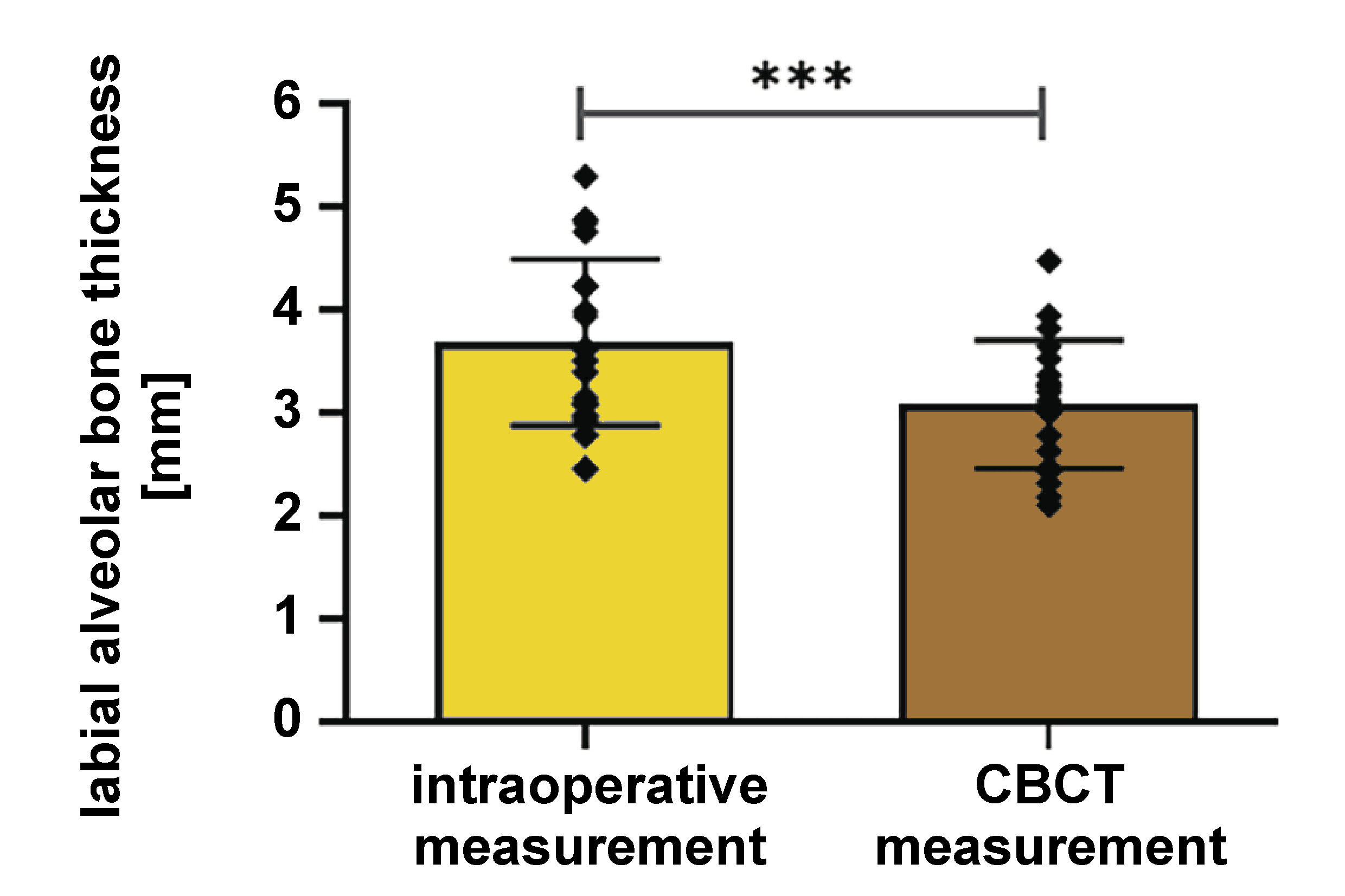

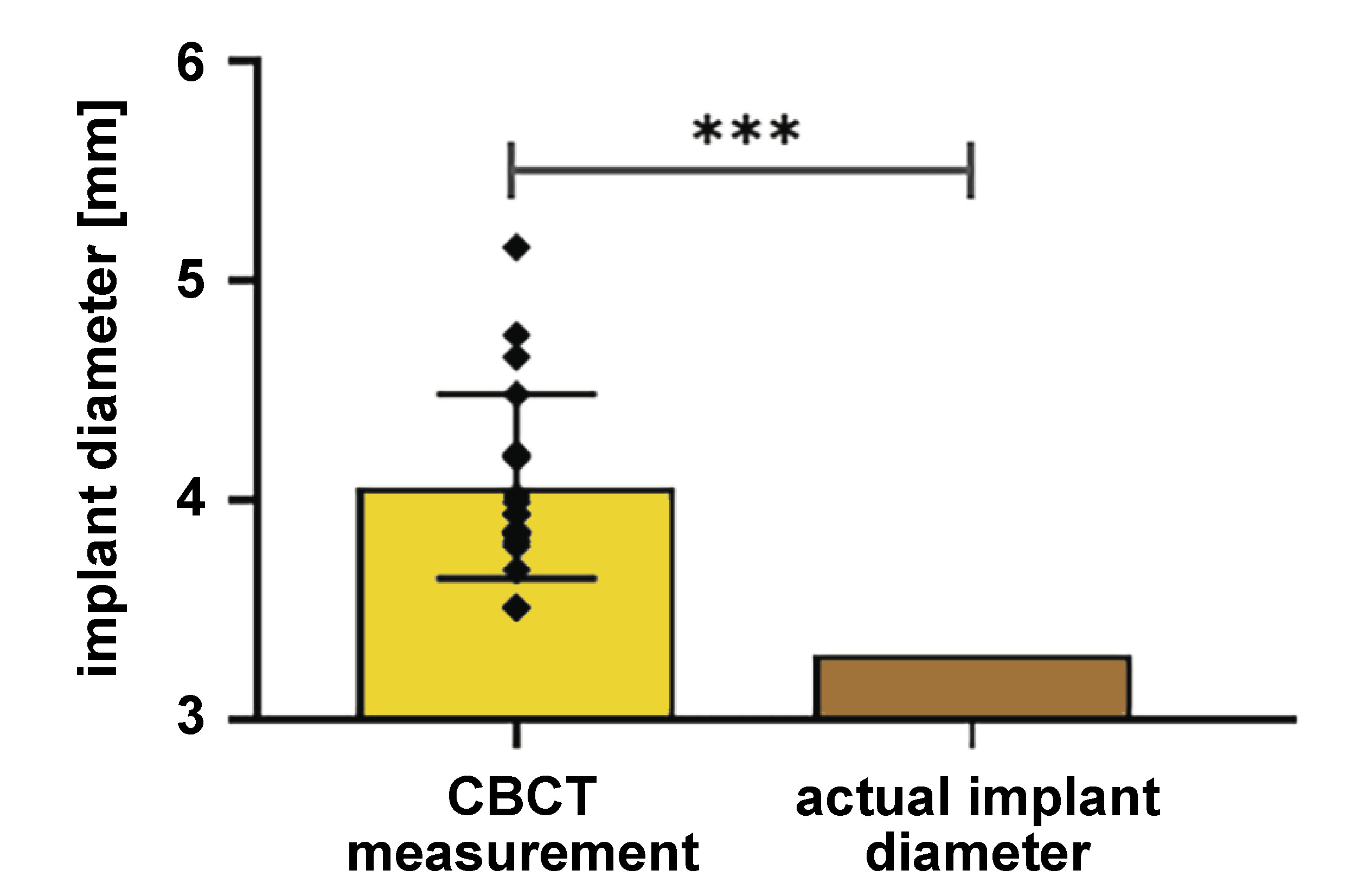

Results. Twenty patients were recruited from the Department of General Dentistry at the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China, from February 2023 to October 2023. In total, 20 implants with a diameter of 3.3 mm were placed surgically. The average distance from the labial alveolar bone surface at the bone crest level to the implant neck in the group of 20 patients, obtained through the intraoperative measurement, was 3.7 ±0.8 mm. The corresponding average value based on the CBCT data of the 20 patients was 3.1 ±0.6 mm. A significant difference was observed between the 2 methods (p < 0.001). The average diameter of the 20 implants measured using the CBCT scans was 4.1 ±0.4 mm, which was significantly greater than the actual implant diameter of 3.3 mm.

Conclusions. The distance from the labial alveolar bone surface at the bone crest level to the implant neck, which comprises the thickness of the labial alveolar bone and the jumping gap, was smaller according to the CBCT data than the actual values obtained from intraoperative measurements. However, the average diameter of the 20 implants measured using the CBCT scans exceeded the actual implant diameter of 3.3 mm. When assessing the thickness of the labial alveolar bone around implants in the maxillary anterior region using CBCT during follow-up, a moderate underestimation of the labial bone thickness may occur.

Keywords: CBCT, measurement method, immediate implantation, labial alveolar bone thickness

Introduction

Immediate implantation in the maxillary anterior region has been gaining increasing attention.1 A growing number of studies now focus on achieving stable and satisfactory outcomes in immediate implant placement.2, 3, 4 The advantages of immediate implantation are manifold, including shortening the edentulous period, reducing the number of surgical procedures and preserving an intact extraction socket.5 The presence of complete socket walls also simplifies and facilitates the placement of low-substitution bone graft materials within the jumping gap.

The thickness of the labial alveolar bone surrounding dental implants is a critical determinant of both alveolar bone stability and esthetic outcomes.6 It can also serve as a predictor of esthetic results and potential complications.7, 8 However, improper three-dimensional (3D) implant positioning may result in labial alveolar bone loss, thereby compromising the stability and esthetics of the final restoration.9

Ideal implant placement in the maxillary anterior region requires precise positioning in the mesiodistal, buccolingual and apicocoronal dimensions, along with correct angulation. To guide this process, the proposed assessments categorize implant sites into ‘comfort’ and ‘danger’ zones.10 In the buccolingual dimension, implants should be positioned 1 mm palatal to an imaginary line drawn through the emergence profile of the adjacent teeth.10

To fulfill the requirements for immediate implantation, the ideal implant position is adjacent to the palatal bone wall of the alveolar socket, which naturally creates a jumping gap between the implant and the labial bone wall. In CBCT images, however, the thickness of the labial alveolar bone surrounding the implant comprises both the labial socket wall and the jumping gap, as this gap is tightly packed with a non-absorbable bone graft material. New bone formation occurs as the osteoblasts originating from the alveolar socket migrate into the graft material, although some resorption of the labial socket wall may occur simultaneously. In this study, the labial alveolar bone thickness of the implant is defined as the distance from the labial bone surface at the bone crest level to the implant neck.

Studies have demonstrated that the postoperative thickness of the labial bone has a significant impact on the success of implant restorations.11 An insufficient labial bone thickness around the implant is associated with an increased risk of peri-implant marginal bone loss, and marginal bone loss exceeding the limits of physiological remodeling is considered a diagnostic criterion for peri-implant disease.12, 13 Currently, the assessment of the labial bone thickness around implants relies primarily on CBCT.14, 15 In addition, CBCT plays an increasingly important role in the customization of implant surgery and in clinical decision-making for immediate implantation by enabling the evaluation of the sagittal root position of maxillary anterior teeth.16, 17 However, discrepancies have been noted between CBCT interpretations and intraoperative findings. Several studies have reported an apparent increase in the implant diameter in CBCT in vitro, as well as the underestimation of the labial bone thickness in fresh-frozen human cadaver heads.18, 19

To evaluate the precision of the CBCT measurements of the postoperative labial alveolar bone thickness, the present study compared the intraoperative measurements obtained during immediate implant placement with the corresponding postoperative CBCT data. This comparative analysis will help improve the accuracy of monitoring the actual labial bone thickness around implants during follow-up using CBCT.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

This study is an in vivo CBCT agreement study evaluating the measurement of the postoperative labial alveolar bone thickness in the maxillary anterior region. From February 2023 to October 2023, patients presenting with dental trauma that resulted in teeth deemed to have a hopeless prognosis, willing to undergo implant restoration, were recruited from the Department of General Dentistry at the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) indication for the traumatic extraction of maxillary anterior teeth; (3) mouth opening greater than 30 mm; and (4) stable occlusion of the proximal and mesial/distal teeth adjacent to the affected site. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) insufficient distance between the implant site and the alveolar socket walls; (2) defects in the labial bone plate; and (3) untreated severe caries or uncontrolled periodontitis in the adjacent teeth. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China (SH9H-2022-T358-1). All patients signed informed consent forms. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

After screening patients according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, eligible participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, and subsequently provided written informed consent. All implant surgeries were performed by the same experienced surgeon in accordance with each patient’s treatment plan.

The surgical procedure was conducted in the following steps. Patients first rinsed their mouths with a 2.5% iodophor intraoral antiseptic for 1 min. Standard surgical disinfection protocols were then performed, and sterile drapes were applied. Under local anesthesia (Primacaine™; Acteon, Merignac, France), a micro-crestal flap technique was used. A crevicular incision was made to create a micro-flap, and a full-thickness flap was elevated to expose the cervical areas of the adjacent teeth and the alveolar crest at the extraction site. Minimally invasive tooth extraction was carried out under direct visualization. After verifying the integrity of the alveolar bone walls, a 3.3-millimeter bone-level titanium (Ti) implant (SLA type; Straumann Group, Basel, Switzerland) was placed into the extraction socket.

Intraoperative measurements were obtained using a periodontal probe and documented with photographs. Bio-Oss® Collagen (Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) was compactly placed into the jumping gap. A CBCT scan (ProMax® 3D; 96 kV, 5.6 mA, exposure time: 12.094 s, voxel size: 0.2 mm; field of view (FOV): 13.0 cm × 9.0 cm; Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland) was performed immediately after implant placement.

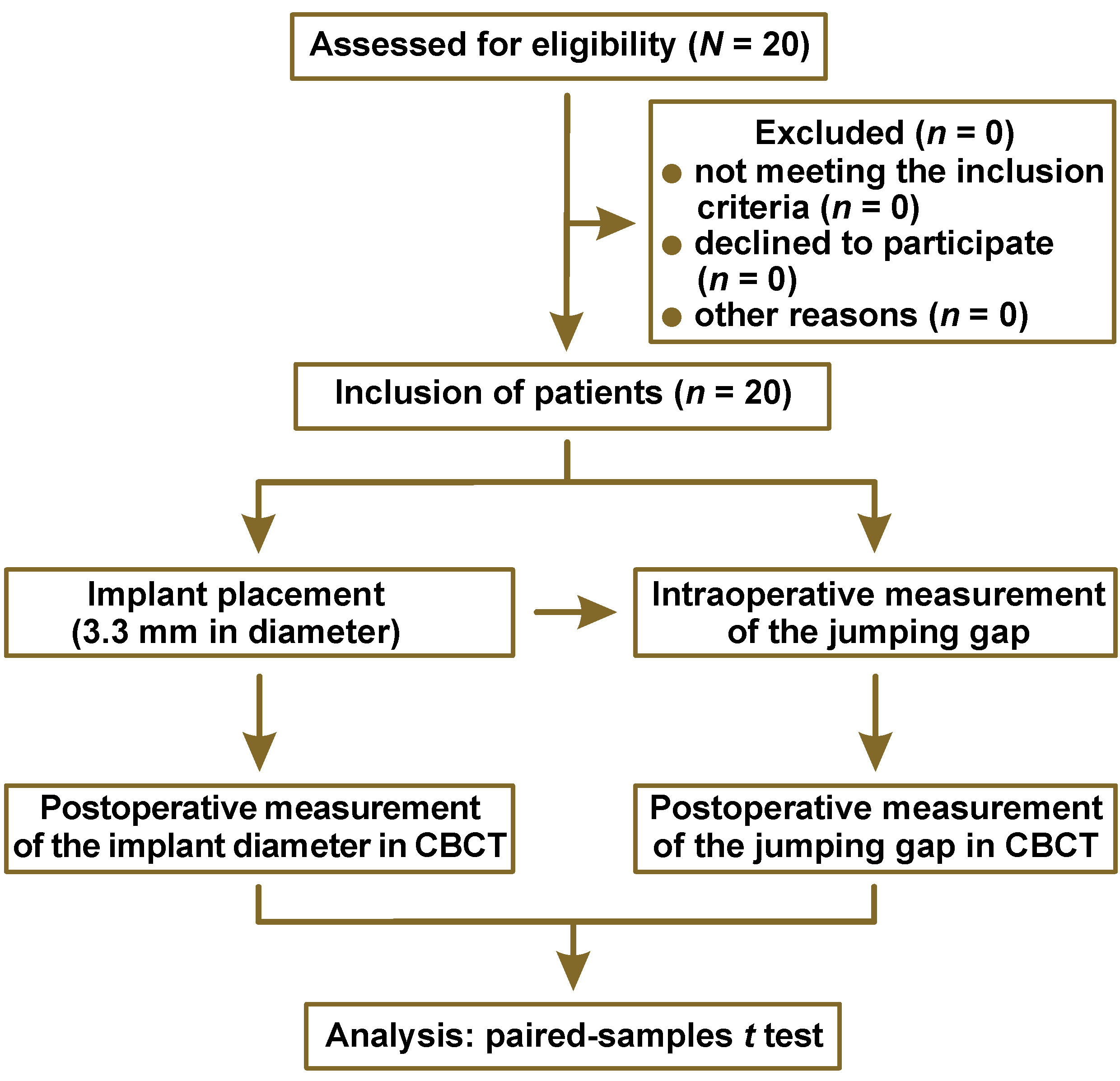

The study workflow is shown in Figure 1.

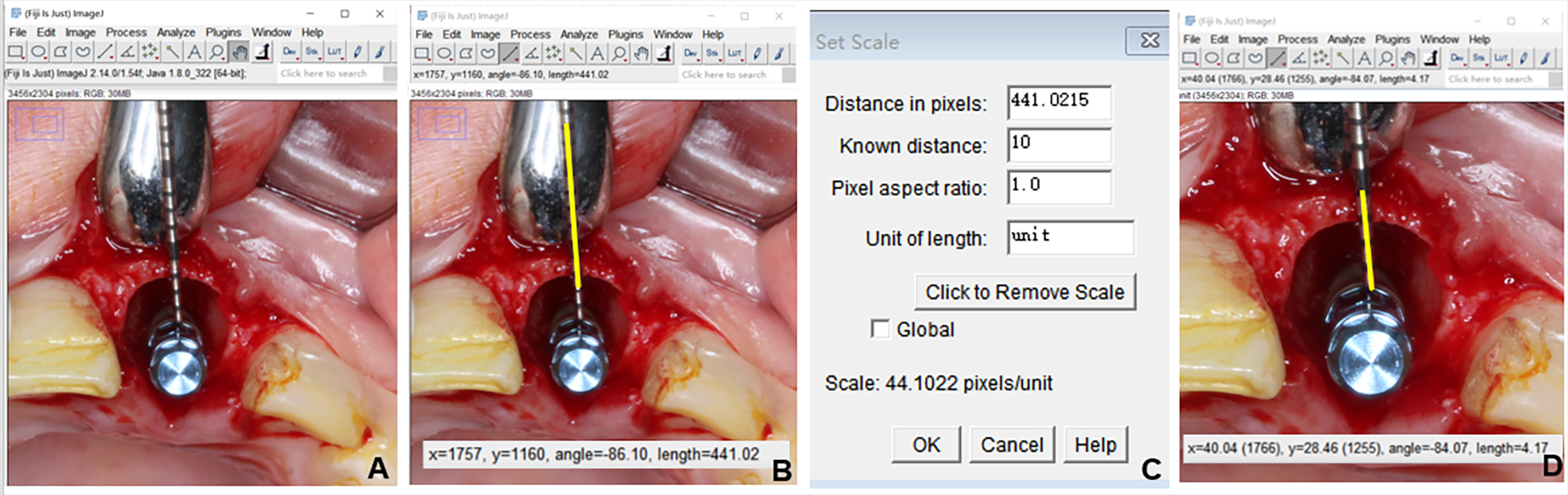

Intraoperative measurement of the labial alveolar bone thickness of the implant

The distance from the labial bone surface at the bone crest level to the implant neck was measured intraoperatively using a standard periodontal probe. To ensure measurement accuracy, the probe was calibrated with the same steel ruler before each use. Photographs were then taken and the corresponding distance in the images was measured using the ImageJ software (https://imagej.net/ij), as shown in Figure 2. All measurements were independently performed by 2 trained assessors to minimize the observer bias.

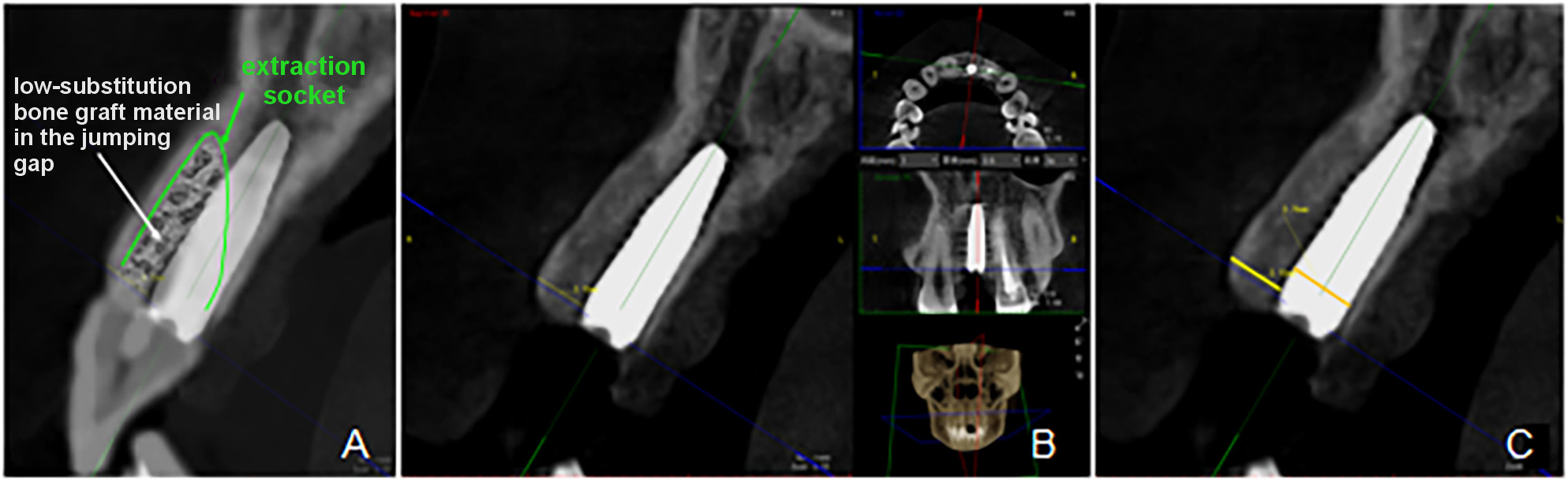

Postoperative measurement of the labial alveolar bone thickness of the implant with the CBCT data

The SmartVPro software, v. 2.1.1.4895 (LargeV, Beijing, China), equipped with a proprietary linear measurement tool, was used to measure the labial alveolar bone thickness and the implant diameter in the multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) CBCT scans obtained immediately postoperatively. The focal planes of the CBCT scans were adjusted to the center of the implant in both the mesiodistal and buccolingual dimensions,20 with the oblique sagittal view oriented perpendicular to the dental arch.

In the CBCT images, the labial alveolar bone thickness – comprising the labial socket wall and the jumping gap filled with Bio-Oss Collagen – was measured at the cervical level of the implant, as illustrated in Figure 3. All measurements were independently performed by 2 trained assessors to minimize the observer bias.

Statistical analysis

The measurement data was statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v. 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). All data is presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ±SD). The one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess normality. Depending on the distribution characteristics, the one-sample t test and the paired-samples t tests were performed for statistical comparisons. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 20 patients were included in the study, with a mean age of 34.7 years (range: 23–53 years). The cohort consisted of 8 males and 12 females. In total, 20 implants were placed in the maxillary anterior region, including 15 Straumann® bone-level tapered implants and 5 Straumann® bone-level implants. The participants’ demographic and clinical data is summarized in Table 1.

Measurement of the labial alveolar bone thickness of the implant

No statistically significant difference was observed between the intraoperative measurements of the distance from the labial alveolar bone surface at the bone crest level to the implant neck obtained by 2 trained assessors using a standard periodontal probe (t = 1.67; p = 0.112). These measurements are summarized in Table 2. The mean intraoperative distance for the 20 patients was 3.7 ±0.8 mm.

Similarly, no significant difference was found between the labial alveolar bone thickness measurements obtained from CBCT by the 2 assessors (t = 0.94; p = 0.360), as shown in Table 3. The mean labial alveolar crest thickness measured in immediate postoperative CBCT was 3.1 ±0.6 mm.

A significant difference was observed between the intraoperative measurements and the CBCT measurements in the immediate postoperative period (t = 4.85; p < 0.001). There was a positive correlation between the 2 sets of measurements (r = 0.726; p < 0.001). The results are presented in Figure 4.

Implant diameter measurement

The mean diameter of the 20 implants measured by CBCT was 4.1 ±0.4 mm. The actual diameter of the implant was 3.3 mm. There was a statistically significant difference (t = 8.17; p < 0.001) between the diameters measured in the CBCT images and the actual value. The results are presented in Figure 5.

Discussion

Immediate implantation offers the advantages of reducing the duration of edentulousness and minimizing the number of clinical visits.11 As reported in the literature, over a 5-year follow-up period, no significant differences were observed between immediate and delayed implants regarding clinical outcomes, including the implant success rates and the preservation of the alveolar bone volume.5, 21 Additionally, clinical evidence suggests that patients with a thin gingival phenotype or a minor loss of the labial lateral bone plate can achieve stable restorative outcomes over long-term follow-up with immediate implant placement.22 The effective management of both peri-implant soft and hard tissues is crucial for ensuring the predictable success of immediate implants.23, 24, 25

Achieving an ideal 3D implant position is one of the most critical factors for ensuring long-term functional and esthetic outcomes in implant restorations. The thickness of the labial bone at the implant neck after immediate implantation is a key predictor of implant prognosis.26 Evidence shows that in the maxillary anterior region, when the implant neck lies less than 1.5 mm from the margin of the labial bone, greater vertical bone resorption can occur, accompanied by a reduction in the width of keratinized gingiva and decreased resistance to peri-implantitis.27 Understanding the pattern of bone resorption is therefore essential. Peri-implant buccolingual bone resorption occurs predominantly about 1 mm apical to the implant platform, with the degree of resorption gradually diminishing toward the apex. Moreover, after immediate implantation, the labial alveolar bone wall is particularly susceptible to resorption – more so than the palatal wall – due to lip muscle pressure. Thus, the labial alveolar bone thickness can be regarded as a critical indicator for predicting the long-term success of implant restorations.28

With the widespread adoption of CBCT, it has become an essential diagnostic imaging tool in implant treatment. Cone-beam computed tomography enables the 3D visualization of the anatomical morphology of the alveolar bone and the peri-implant structures. However, artifacts – the virtual distortions produced during image reconstruction – can compromise image quality by reducing contrast between the adjacent structures.21 Among these, metal artifacts exert the greatest influence. Since CBCT operates at lower energy levels than the conventional computed tomography (CT), it generates more pronounced artifacts, which in turn affect the visibility of peri-implant tissues and measurement accuracy.29 Evidence also indicates that CBCT is less sensitive in detecting small areas of peri-implant bone loss.30 In this study, all implants used were 3.3 mm in diameter, yet the implant diameters measured on postoperative CBCT averaged 4.1 mm, which constituted a statistically significant difference. This discrepancy may be attributable to metal artifacts and the cupping artifact associated with the cylindrical geometry of the implant.29 Recent studies further report that Ti implants produce fewer artifacts than zirconia implants, and that artifact intensity can be reduced by increasing the CBCT tube voltage or by applying data processing algorithms that reduce metal artifacts.31

A study conducted on fresh-frozen human cadaver heads reported a 15% increase in implant diameter.19 In the present study, a blooming percentage of up to 24% was observed, which has important implications for assessing the labial bone thickness in CBCT. In living subjects, the soft tissues surrounding the implant, as well as moisture within bone and blood, can absorb X-rays, potentially influencing the CBCT grayscale values and measurement accuracy.32, 33 The presence of soft tissues and the absence of moisture changes typically introduced by freezing and thawing may further contribute to a greater underestimation of the labial bone thickness in vivo.

Although diagnosing peri-implant pathology based on the radiographic assessment of the bone plate thickness is inherently challenging, especially at the early stages of disease progression,34 the evaluation of the labial bone plate thickness using CBCT after implant placement remains a critical component of postoperative follow-up. However, current studies have insufficiently addressed the accuracy of CBCT and the factors that may influence the reliability of its measurements.35 In vitro research has shown that CBCT detects labial bone plates of ≤0.5 mm around implants at a rate of less than 20%; yet, for every 1-mm increase in the bone plate thickness, the detection rate increases by 30.6%.23 In the present study, the CBCT measurements demonstrated a 0.6-mm reduction in the labial alveolar bone thickness of the implant as compared to the intraoperative measurements, indicating a pronounced tendency for CBCT to underestimate the true labial bone thickness. This finding aligns with previous in vitro studies using ribs and chilled skulls.24, 35 Such underestimation may be attributable to the metal artifacts generated by the implant, as well as the influence of the surrounding anatomical structures. Notably, this tendency becomes further amplified when the labial bone thickness is less than 1 mm.36

This study suggests that when the labial alveolar bone thickness around implants in the maxillary anterior region is assessed using CBCT during follow-up, a moderate overestimation of the buccal bone thickness is acceptable. Therefore, implant stability should be evaluated promptly using complementary methods, such as the implant stability quotient (ISQ) and the patient’s subjective perception, to ensure accurate clinical judgment.

Limitations

Owing to the relatively small sample size and the limited variability in implant types, the findings of this study have certain limitations. To reduce bias and enhance external validity, future research should include multicenter studies with larger sample sizes and incorporate implants from different manufacturers to better observe radiographic variations across implant systems.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of the present study, the labial alveolar bone thickness of the implants in the maxillary anterior region measured in CBCT was consistently lower than the intraoperative values. In contrast, the mean implant diameter measured in CBCT exceeded the actual implant diameter of 3.3 mm. Therefore, when assessing the labial alveolar bone thickness around implants in the maxillary anterior region during follow-up, a moderate overestimation of the CBCT-derived values is permissible.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China (SH9H-2022-T358-1). All patients signed informed consent forms. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.