Abstract

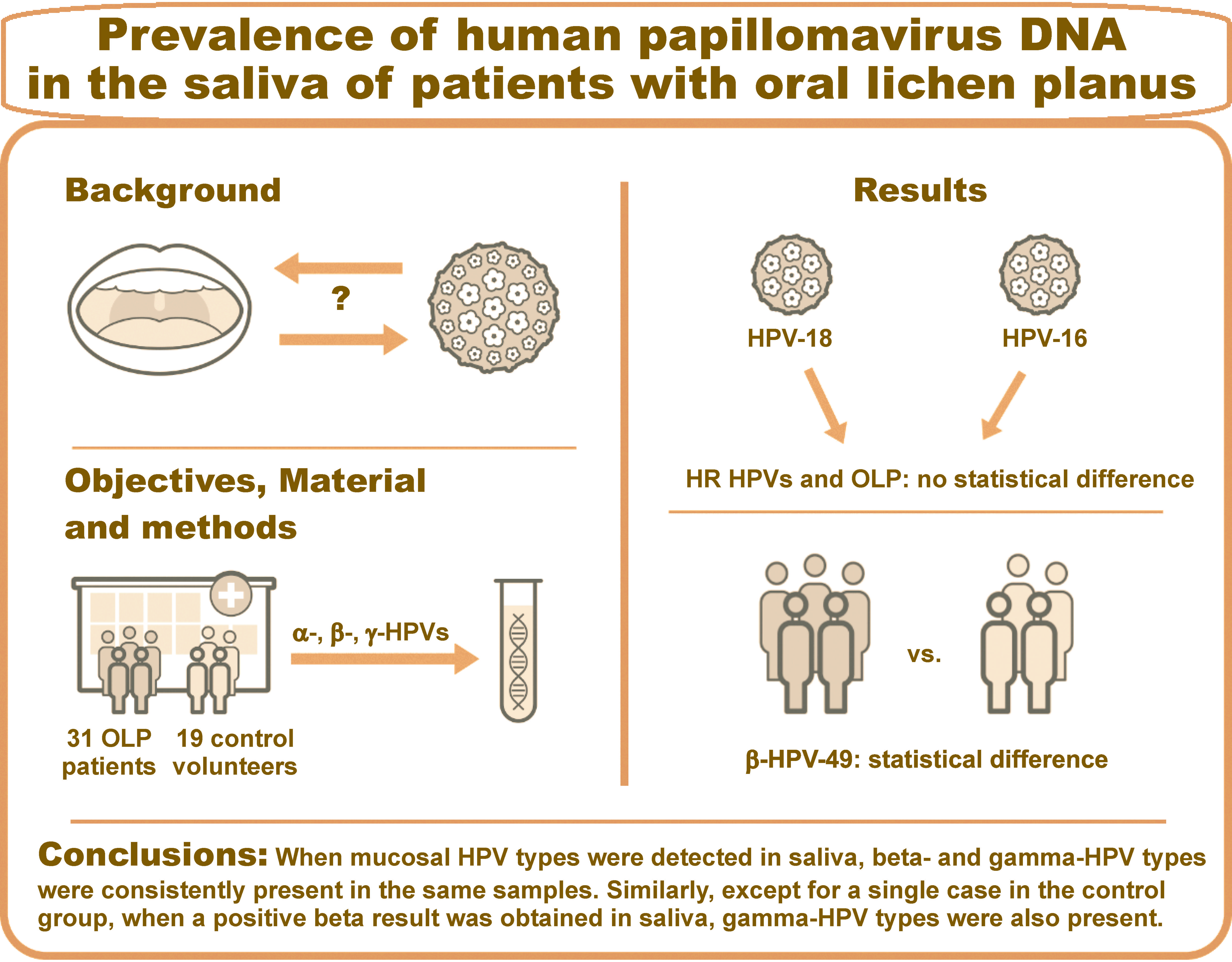

Background. Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory T cell-mediated disease that is classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an oral potentially malignant disorder (OPMD). Despite the heightened interest in the influence of human papillomavirus (HPV) on oral cancer, the overall incidence of HPV affecting patients with OLP remains inconclusive.

Objectives. The study aimed to evaluate the presence of alpha-, beta- and gamma-HPVs in saliva samples collected from 31 OLP patients and 19 control volunteers. This hospital-based study has the advantage of providing comprehensive clinical data and oral health history, along with saliva analysis for HPV in the specific OPMD.

Material and methods. The DNA extracted from saliva samples obtained from patients with a clinical presentation of OLP, classified as ICD-10:L43, was analyzed using HPV type-specific bead-based multiplex genotyping assays to detect 21 mucosal alpha-, 46 beta- and 52 gamma-HPV types.

Results. The most common HPV type was HPV-49, with a statistically significant difference found between the OLP and control groups (p < 0.05). There was no statistical correlation between high-risk (HR) HPVs (HPV-16 and HPV-18) and OLP in the studied population. Positive results for the mucosal types of DNA in the saliva were associated with the positive beta and gamma types that were consistently identified in the analyzed biomaterial.

Conclusions. Beta-HPV-49 was significantly more prevalent in the saliva of patients with OLP. There was no relationship between HR HPVs and the OLP status, which represents the difference between OLP studied in this research and other OPMDs.

Keywords: saliva, oncology, oral lichen planus, mouth neoplasms, human papillomavirus

Introduction

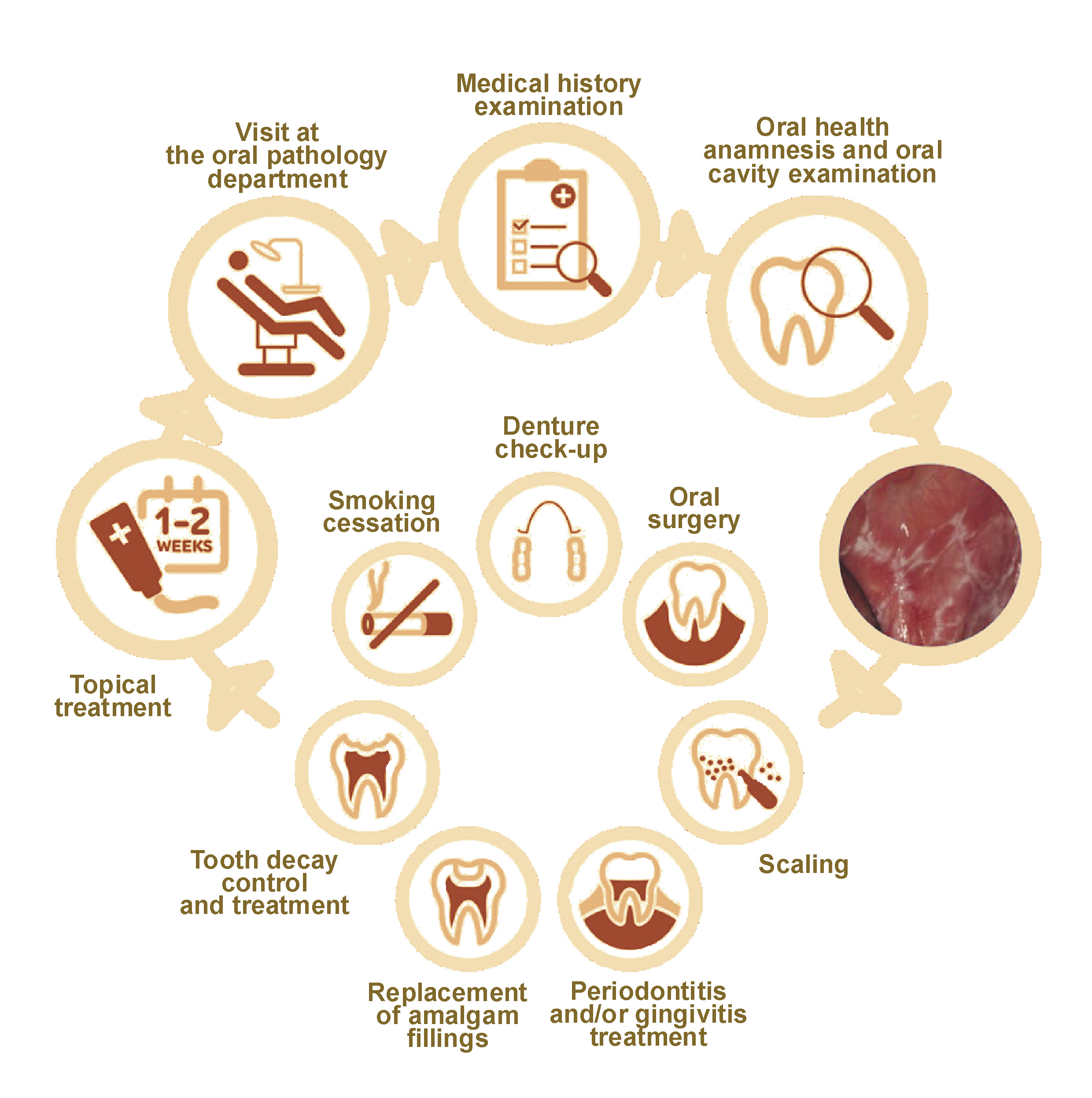

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory T-cell-mediated disease classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an oral potentially malignant disorder (OPMD), with an overall incidence of 0.49–1.43% in the general population.1 Oral lichen planus is a chronic condition2, 3, 4 that is not related to tobacco smoking or betel chewing, two widely discussed risk factors for OPMDs.5 The possible association of hormonal changes with the development of OLP has been suggested since the disorder exhibited an increased incidence in post- and peri-menopausal non-smoking and non-alcohol-drinking women.6, 7, 8 Other causal links for OLP formation include diabetes mellitus, infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) and stress.6, 7 The clinical management of OLP is of great importance, as there are no established programs for primary prevention beyond the avoidance of tobacco and the cessation of alcohol consumption.2, 9 Despite the considerable interest in the influence of different viral infections on OPMDs, it has not been conclusively defined how the presence of different human papillomaviruses (HPVs) affects OLP patients and influences the eventual progression to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). The diagnostic process of OLP in the dental office is presented in Figure 1.

Human papillomaviruses are a family of double-stranded DNA oncoviruses that are associated with invasive malignancies. They are divided into 3 genera: Alphapapillomavirus (alpha-HPV), which includes 12 mucosal high-risk (HR) HPV types, namely HPV-16, -18, -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -56, -58, and -5910, 11, 12; Betapapillomavirus (beta-HPV); and Gammapapillomavirus (gamma-HPV), predominantly isolated from skin. However, a variety of HPV types may be present in different bodily subsites.13 In particular, there is a connection at the level of the genital mucosa, the upper respiratory tract and the skin.14 Mucosal HR alpha-HPV types are considered well-established risk factors for anogenital tract squamous cell carcinoma15 and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) in the area of the tonsils and base of the tongue at the oropharynx.16, 17 Mucosal HPVs have been associated with the majority of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) cases in the United States and other developed countries, and a minority of HNSCC cases have stemmed from palatine tonsils and lingual tonsils.18, 19

Cutaneous HPV types may also have an influence on carcinogenesis. The epidemiological and biological models support the synergistic cooperation between beta-HPVs and ultraviolet (UV) radiation in this process.12, 20 Beta-HPV infection plays a “hit-and-run” role in the initial phase of skin carcinogenesis, and an optional role for tumor cell growth once they have become malignant.12, 20, 21 These types of viruses are subsequently divided into 5 species (beta-1 to beta-5), with the first two including the majority of beta types present in the skin of healthy individuals,20, 22 and beta-2 mostly found in squamous cell carcinomas.23 However, while the majority of the beta subtypes are found on the skin, there have been indications suggesting a dual tissue tropism for specific HPV types in the oral and nasal mucosa.20 Interestingly, in vivo and in vitro experimental models have demonstrated that beta-3 HPV-49 shares biological properties with mucosal HR HPV types, as it immortalizes human primary keratinocytes, which serve as the natural host cells for HPVs.12

The gamma genus comprises 27 species, yet no studies have evaluated the possible association of this HPV type with human carcinogenesis, except for a functional in vitro experimental model that aimed to highlight the transforming properties of gamma-24 HPV-197.20 While the available data confirms that gamma types can be detected in the anal mucosal epithelium, the results of an extensive epidemiological nested case–control study suggest a broader role for HPVs in HNSCC etiology, as indicated by the associations with gamma-11 and gamma-12 HPV species.24 The study also suggests that easily collected oral samples could provide a prospective biomarker for the prognosis of HNSCC.24

Further investigation is required to elucidate the relationship between OPMDs and HPV infection. In one of the studies, the oral mucosal cells from individuals with OLP presented signs of apoptosis, suggesting similarities to HPV infection.25 However, the data revealed significant variations.25, 26, 27 Another study suggested that a cooperation between p53 and heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), as well as between HPV-16/18 and HSP90, may affect the biological behavior of OLP. The observed expression of HSP90 and p53 in OLP, as well as the increase in these proteins upon presentation of OSCC, suggests that these factors participate in the malignant transformation of OLP.28

Saliva represents a non-invasive biosample for laboratory diagnostics in the oral cavity.29, 30, 31, 32 Previous studies have primarily focused on detecting a limited number of HPV types in OLP, and comprehensive genotyping of all 3 genera in the saliva of OLP patients has not been conducted. Given the differences in the pathophysiology of OLP compared to other OPMDs, we hypothesize that the composition of salivary viruses in patients with OLP may differ. Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the presence of alpha-, beta- and gamma-HPVs in saliva samples collected from 31 OLP patients and 19 control volunteers using highly sensitive HPV genotyping assays.33

Material and methods

Study sample

The study population comprised individuals with a clinical diagnosis of OLP who had agreed to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: a histopathological and/or clinical diagnosis of OLP, classified as ICD-10:L43 according to the WHO criteria34; and patients enrolled at the Oral Pathology Outpatient Clinic, Department of Oral Pathology, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland, within a 9-month period. No age range was imposed. The exclusion criteria encompassed patients who had undergone any cancer therapies (oral or other) upon admission, as well as those with clinical and histopathological features of oral lichenoid lesions classified as oral lichenoid contact lesions, oral lichenoid drug reactions, and graft-versus-host disease at the time of the research.

The data collected from patients’ medical histories after pseudo-anonymization included sociodemographic information (age, sex, place of residence) and medical profiles of the participants. The demographic data analysis was profiled based on patient disclosure (Table 1). The relationship between tobacco consumption and the duration of smoking and/or cessation was considered. Patients were assigned to experimental groups using a simple randomization method.

To provide a clinical evaluation of the control group (19 subjects), volunteers were recruited from the dentists working in the clinic, dental assistants and administrative personnel who agreed to participate in the study. While some individuals in the control group demonstrated higher than average oral hygiene (i.e., dentists), the bias was minimized by the inclusion of administrative workers in the study. The exclusion criteria for the control group consisted of the current diagnosis of OLP or any alterations pertaining to OPMDs and/or periodontitis. The inclusion criteria encompassed a healthy state of the oral cavity, as well as not undergoing any generalized treatment or cancer treatment at the time of saliva collection.

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University, Poland (approval No. KB760/2021). The participants provided written informed consent after receiving information about the project and prior to the collection of biomaterials.

Clinical evaluation of the oral health status

The analysis of the patient’s oral health status and clinical OLP presentation was performed by the oral pathology specialist. Histopathological diagnostics were offered to patients with persisting lesions of uncertain clinical features, when there was a progression of the lesion, and for the exclusion or confirmation of epithelial dysplasia. This clinical intervention was selected to minimize unnecessary scarring of the lesion, as discussed by González-Moles et al.1 Saliva samples were collected from the patients at the beginning of the visit, following the preliminary oral health examination and prior to invasive dental procedures. The protocol for saliva collection has been previously described.30 Afterward, the salivary samples were transported on dry ice to the Epigenomics and Mechanisms Branch of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (Lyon, France) for HPV subtype analysis. The results of the HPV analysis were scored by a laboratory professional who was blinded to the condition and experimental group division.

DNA extraction

The extraction of DNA from saliva was performed using the BioRobot® EZ1 DSP Workstation with the EZ1 DNA tissue kit, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Briefly, following centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 10 min, the cell pellets were incubated in proteinase K and G2 buffer (Qiagen) at 56°C for 3 h. Subsequently, the DNA was extracted into a 50-μL Eppendorf tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

Human papillomavirus DNA analysis

Molecular diagnostics, namely DNA extraction and HPV DNA genotyping, were performed at the Epigenomics and Mechanisms Branch of the IARC (Lyon, France).

The extracted DNA was analyzed using an HPV type-specific multiplex genotyping test (E7-MPG), as previously reported.35 This molecular assay integrates multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and bead-based Luminex technology (Luminex Corporation, Austin, USA). The multiplex type-specific PCR method uses specific primers for the detection of 21 mucosal HR alpha-HPV types (-6, -11, -16, -18, -26, -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -53, -56, -58, -59, -66, -68, -70, -73, -82), 46 beta-HPVs from β-species 1 (-5, -8, -12, -14, -19, -20, -21, -24, -25, -36, -47, -93, -98, -99, -105, -118, -124, -143, and -152), β-species 2 (-9, -15, -17, -22, -23, -37, -38, -80, -100, -104, -107, -110, -111, -113, -120, -122, -145, -151, -159, and -174), β-species 3 (-49, -75, -76, and -115), β-species 4 (-92), and β-species 5 (-96 and -150); and 52 gamma-HPVs from γ-species 1 (-4, -65, -95, and -173), γ-species 2 (-48 and -200), γ-species 3 (-50), γ-species 4 (-156), γ-species 5 (-60 and -88), γ-species 6 (-101, -103 and -108), γ-species 7 (-109, -123, -134, -149, and -170), γ-species 8 (-112, -119, -164, and -168), γ-species 9 (-116 and -129), γ-species 10 (-121, -130, -133, and -180), γ-species 11 (-126, -169, -171, and -202), γ-species 12 (-127, -132, -148, -165, and -199), γ-species 13 (-128), γ-species 14 (-131), γ-species 15 (-179), γ-species 18 (-156), γ-species 19 (-161, -162 and -166), γ-species 20 (-163), γ-species 21 (-167), γ-species 22 (-172), γ-species 23 (-175), γ-species 24 (-178 and -197), γ-species 25 (-184), and γ-species 27 (-201), as well as SD2.36 An additional set of primers for β-globin was also included. After PCR amplification, 10 μL of each reaction mixture was analyzed using a Luminex-based assay, as previously described. For each probe, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) obtained when no PCR product was added to the hybridization mixture was considered the background value. The cut-off was computed by adding 5 MFI to ×1.1 of the median background value. All MFI values that exceeded the designated cut-off point were considered positive.35

Statistical analysis

The obtained results were statistically analyzed using STATISTICA™ software, v. 13.3 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA) and the Python Programming Language (RRID:SCR_008394, package Dython, v. 0.7.4; Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, USA). The data was presented as numerical values, percentages, and means with standard deviations. The Shapiro–Wilk test was employed to assess the distribution of the data. The comparisons between the control and patient group variables with a normal distribution were assessed with the use of Student’s t-test for independent variables. The odds ratio (OR), standard error (SE) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated according to Altman.37 The χ2 test of independence was used to identify the relationship between categorical variables, and the Phi coefficient or Cramér’s V was employed to assess the effect size of the relationship between binary or multicategorical variables, respectively. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was utilized to ascertain the relationships between continuous variables. The differences were interpreted as statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

General characteristics and clinical evaluation of the study groups

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are provided in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 62.39 ±11.02 years, ranging from 37 to 82 years. The majority of the included patients were from cities with a population exceeding 100,000 inhabitants (n = 12; 38.71%). Oral lichen planus was diagnosed more frequently in women (n = 28; 90.32%) during the ongoing recruitment of patients that persisted for 9 months.

A detailed description of the OLP patients’ oral health is provided in Table 2. The individuals diagnosed with OLP presented additional changes to the oral health status, including desquamative gingivitis (n = 7; 22.58%), xerostomia (n = 2; 6.45%), geographic tongue (n = 2; 6.45%), and bruxism (n = 2; 6.45%).

A histopathological analysis of any OLP lesions was performed in 13 subjects (41.94%). The pathologist observed erosive and/or high-grade changes in 6 subjects (19.35%). The three most common areas affected by OLP were the cheeks (n = 15; 48.39%), cheeks and tongue (n = 7; 22.58%), and the molar triangle (n = 2; 6.45%).

A total of 3 subjects (9.68%) reported a generalized disorder of lichen planus (skin type) and had either consulted with, or had been consulted by, a dermatologist. The most declared general disorder was diabetes, reported by 4 patients from the study group (12.90%).

The volunteers from the control group (n = 19) declared no smoking habit or use of any other form of tobacco or vaping systems. The examination of the subjects’ oral cavities revealed no significant changes or evidence of OLP or other pathologies.

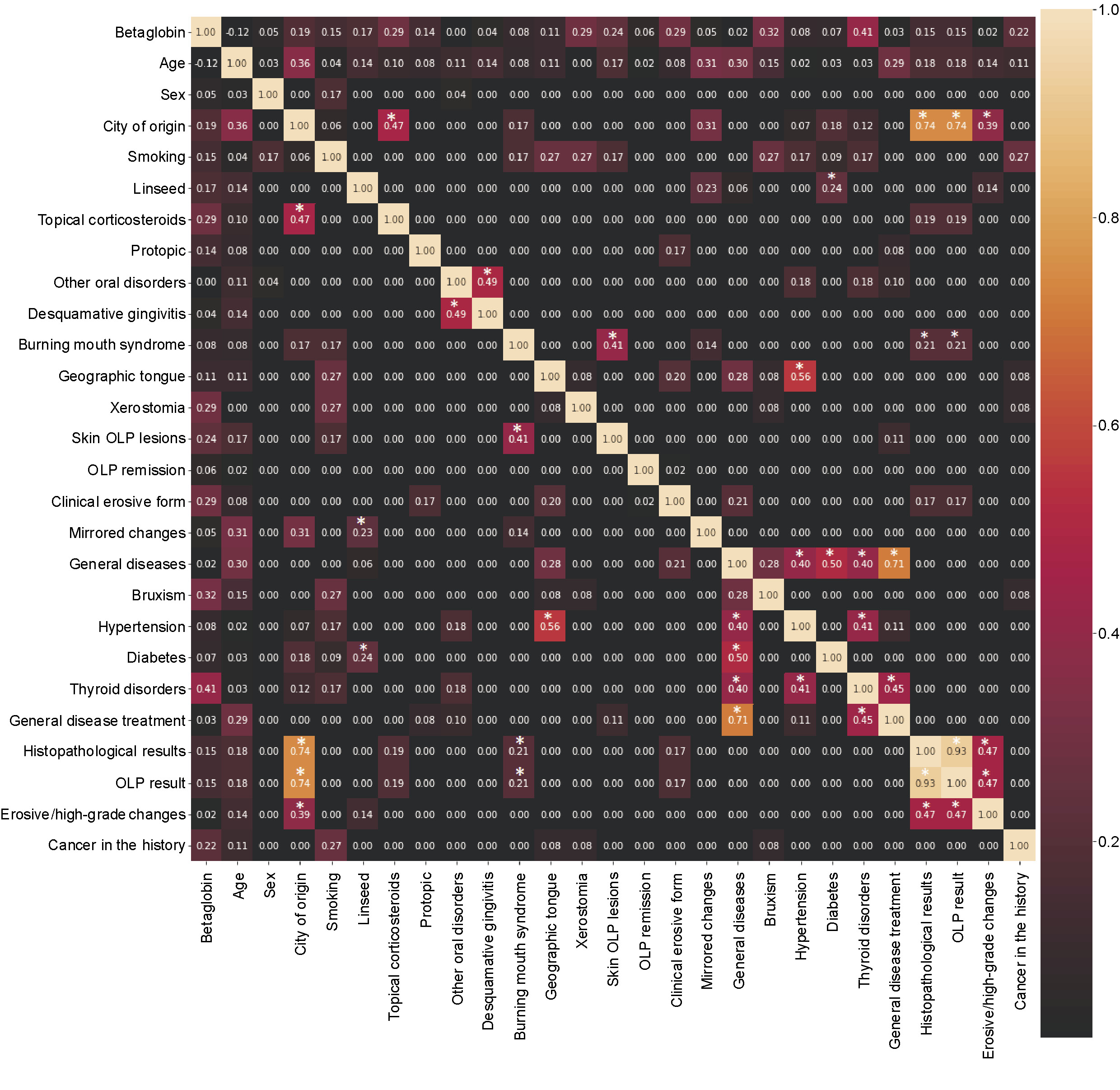

Additionally, the relationships between questionnaire variables are presented in Figure 2. A marked relationship was identified between hypertension and geographic tongue, as well as between the manifestation of skin OLP and the presence of burning mouth syndrome in individuals with OLP.

DNA molecular results

HPV genotyping

For all samples, the presence of high-quality DNA was confirmed by positive PCR amplification of the β-globin gene, as demonstrated in the supplementary materials (available on request from the corresponding author).

The frequencies were compared using the χ2 test.37 Statistically significant values were obtained for the presence of HPV-49 DNA in the saliva of patients from the OLP group when compared to the control group (Table 3). In another part of the analysis, the presence of HPV-17, -24, -47, -104, -105, -113, -143, -4, -121, -123, -130, -134, and -149 was detected in the OLP group but not in the control group, demonstrating HPV-positive OLP.

The well-known oncogenic HPV types 16 and 18 were not detected in the saliva of any patient with OLP.

Regarding the HPV groups, the presence of mucosal types in saliva was accompanied by the detection of beta and gamma types in the analyzed biomaterial. Similarly, with the exception of a single case in the control group, if a positive beta type result was obtained in saliva, gamma-HPV types were also present (supplementary materials).

As a thorough HPV analysis presented in this manuscript is not widely performed, the table enumerating all positive results for the analyzed HPV subtypes is included in the supplementary materials.

Discussion

In the present study, the clinical and histopathological parameters related to OLP status were evaluated for the presence of specific HPV types. The most prevalent condition observed among OLP patients was desquamative gingivitis, which manifested in 22.58% of the subjects. This disorder is characterized by hypersensitivity to a variety of autoimmune diseases.38 The majority of patients were non-smoking women (90.32%), and the mean age of the participants was 62 years, which is consistent with previous OLP studies.39

The most frequently diagnosed HPV type in this study, which exhibited statistical differences between the OLP and control groups, was beta-HPV-49. In a previous study, it has demonstrated a similar ability to degrade p53 as HPV-16 E6 in an E6AP-dependent mechanism.40 Beta HPV-49 was reported in 6% of the participants diagnosed with HNSCC and in 4.6% of controls.41 The HPV-23 subtype was detected in 7 individuals from the study group, with 2 of these patients also being positive for HPV-38. One patient who presented only with HPV-23 has been previously diagnosed and successfully treated for oral cancer, namely OSCC type G1. In a previous study, HPV-23 was identified as the most prevalent type in the oral cavities of healthy individuals.41

In the present research, it was hypothesized that patients with OLP may harbor a distinct HPV profile compared to individuals with other OPMDs, potentially altering the contributions to disease evolution. With respect to HPV groups, the presence of mucosal types in saliva was accompanied by the detection of beta and gamma types in the analyzed biomaterial. Similarly, except for 1 case in the control group, when a positive beta result was obtained in saliva, gamma-HPV was also present. These outcomes provide preliminary evidence that HPV, particularly beyond the alpha genus, could be represented in the saliva of patients with OLP. Further longitudinal, extensive cohort studies are essential to determine whether all HPV genera contribute to disease progression and the malignant potential of OLP.

The methodology employed in the most recent medical literature, along with the type of samples used in the analysis, may significantly affect outcomes, especially in studies based on OPMD samples, where viral diagnostics are not standardized. Several case–control studies have shown a higher prevalence of HPV, including mucosal types HPV-16 and HPV-18, in OLP subjects compared to controls.25 Mohammadi et al. have examined formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples of OLP.25 Surprisingly, based on these findings, 12 samples (48% of all OLP cases) were found to be positive for HPV-16, compared to 6 samples in the control group. The methodology used by the authors included endpoint PCR and different biomaterials.25 In contrast, other studies have failed to detect mucosal HPV in OLP,26, 27 suggesting a potential discrepancy in sample quality. In the present study, no correlation was identified between HPV-16 or HPV-18 and the clinical stage, nor were any results for those HR HPV types obtained using highly sensitive Luminex-based assays. A limitation of this study is that the aliquoting process involved a pre-centrifugation step at 2,500 rpm to remove debris, which has presumably reduced the amount of exfoliated oral cells. Nevertheless, DNA has been successfully extracted from all samples, as evidenced by the amplification of the β-globin gene.

The available medical literature indicates a paucity of participants in most epidemiological studies on OPMDs, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Most of the analyses of HPV DNA in OLP individuals were performed on a relatively small number of samples (less than 30).25, 26, 42 Among the retrospective cohorts, the analyses were conducted on formalin-fixed samples.25, 26, 42, 43 In this regard, our research, which represents a hospital-based study with an average number of volunteers, has the advantage of providing all clinical data, oral health history and saliva analysis.

Conclusions

Statistically significant values were obtained for the presence of HPV-49 in relation to the frequency of individual HPV types in the OLP group. However, its role in the process of potential progression to OSCC remains to be established.

The investigation revealed no significant correlation between the HR HPV (HPV-16 and HPV-18) and OLP in the studied population.

With regard to the presence of HPV groups, the mucosal types were positively diagnosed in saliva, and the beta and gamma types were consistently identified in the analyzed biomaterial. Similarly, except for a single case in the control group, when a positive beta result was obtained in saliva, gamma-HPV was also present.

Even though saliva samples are easy to collect and safe, this medium is not always a reliable source for detecting viral infections. Tissue samples are more likely to provide reliable results, and in cases of non-healing or severe, advanced oral lichen lesions, the presence of HPV infection is a consistent finding.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University, Poland (approval No. KB760/2021). The participants provided written informed consent after receiving information about the project and prior to the collection of biomaterials.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.