Abstract

Background. Obesity and periodontal diseases are associated with oxidative stress activation. Periodontitis and gingivitis are inflammatory diseases that cause systemic and local production of reactive oxygen species, leading to tissue damage. Obesity exacerbates systemic free radical oxidation.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to evaluate the influence of cerium oxide nanoparticles (CNPs) as potential pharmaceutical agents for targeting oxidative stress activation in patients with obesity and periodontal disease.

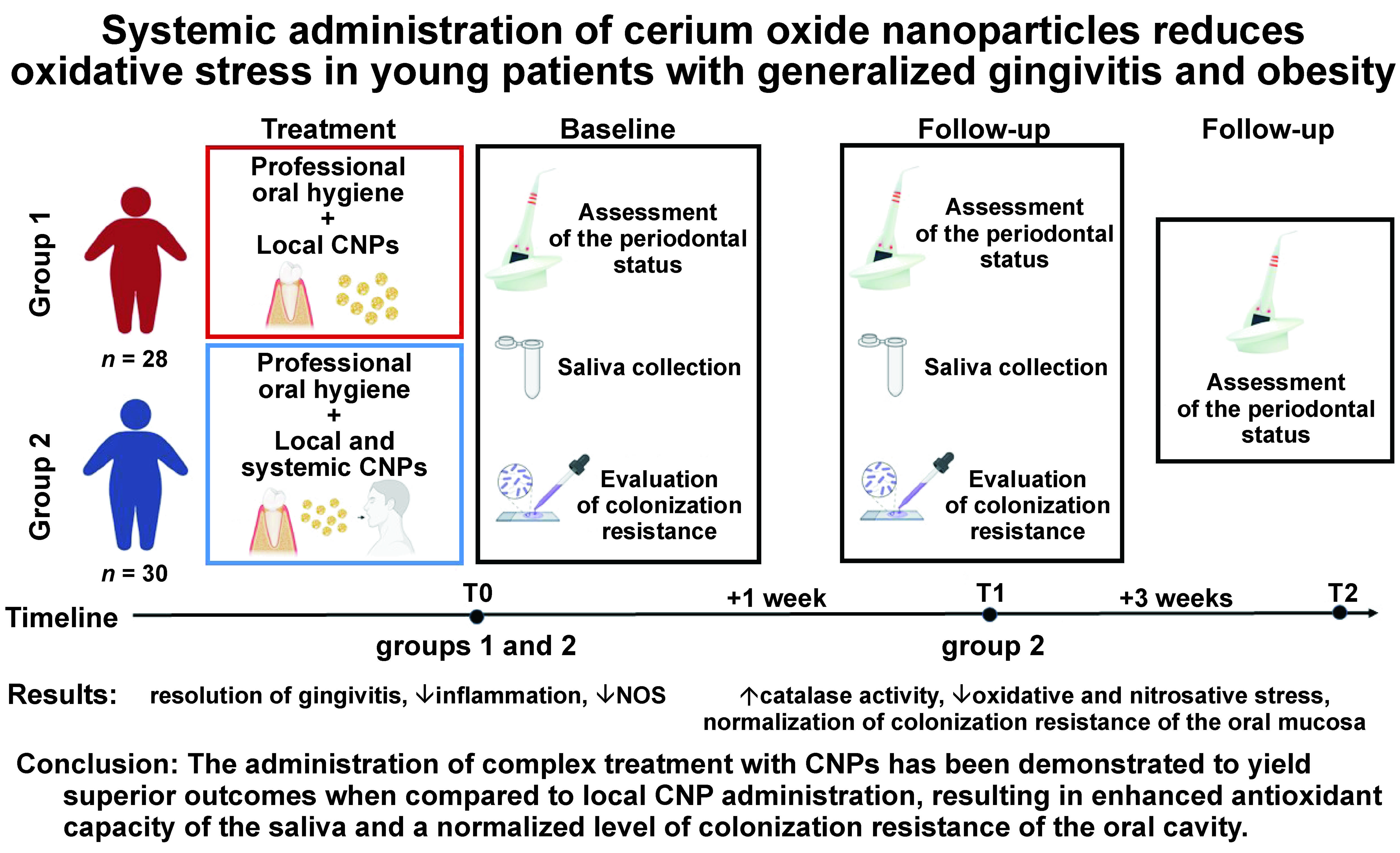

Material and methods. Young patients with obesity and generalized gingivitis were randomly allocated into 2 groups. In the first group (n = 28), a professional oral hygiene procedure was performed, followed by the local application of the Nanosept solution (a formulation comprising CNPs and chlorhexidine digluconate (CHG)). Over the next 5 days, the subjects were instructed to administer the Nanosept solution twice a day on the gums using a cotton sponge for 5 min. The second group (n = 30) was additionally prescribed the antioxidant Cerera (CNPs) for 10 days.

Results. Following treatment in both groups, a complete resolution of gingivitis was registered. In both groups, a significant decrease in salivary mucopolysaccharides and total nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity was observed. However, a significant decrease in oxidative and nitrosative stress markers, as well as an increase in catalase activity were registered only after systemic administration of CNPs. Similarly, the normalization of colonization resistance (CR) was observed only in the second group.

Conclusions. Systemic administration of CNPs in the treatment of obese patients with generalized gingivitis resulted in a decrease in oxidative and nitrosative stress activation in the oral cavity, enhanced antioxidant capacity of the saliva, and normalized the level of CR of the oral cavity.

Keywords: obesity, periodontitis, cerium oxide nanoparticles, nanozyme, clinical trial

Introduction

The prevalence of periodontal diseases is extremely high. The incidence of gingivitis is estimated to range from 50% to 100% among young individuals from different populations.1, 2, 3 Over the past 30 years, the prevalence of periodontitis has notably increased, especially among younger individuals.4 Unmanaged gingivitis has a tendency to progress into periodontitis, particularly in individuals with chronic conditions that affect host immune responses such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, autoimmune conditions, and endocrine diseases. Also, it can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, among others.5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Obesity has been identified as a significant predisposing factor for the development of periodontitis and an element contributing to its severity.10, 11, 12 Young patients who are overweight or obese exhibit a higher prevalence of periodontal diseases compared to individuals with a healthy body mass index (BMI).13, 14

One of the main pathophysiological mechanisms underlying periodontal tissue alterations is the activation of oxidative stress on a local and systemic level.15 In obese individuals, systemic oxidative stress is caused by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6 and leptin into the blood by excess visceral and subcutaneous adipocytes.16 Systemic factors, including hyperglycemia, elevated tissue lipid levels, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, hyperleptinemia, increased muscle activity to support excessive weight, endothelial dysfunction, impaired mitochondrial function, and diet contribute to the development of systemic oxidative stress.8, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Local activation of nitrosative and oxidative stress in the periodontium is caused by the response of polymorphonuclear leukocytes to gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide, leading to respiratory burst and the secretion of inflammatory mediators. Excessive production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) by neutrophils results in increased levels of nitric oxide (NO) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−).22, 23, 24

Cerium oxide nanoparticles (CNPs) exhibit strong enzyme-like activity similar to that of catalase and superoxide dismutase enzymes.25, 26 Compared with traditional non-enzyme antioxidants, such as vitamin C, vitamin E, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and quercetin, which can take part only in 1 redox cycle, CNPs show a capacity for self-regeneration. Within a few days, these particles are ready to neutralize an additional superoxide radical.27

Due to their antioxidant properties, CNPs are widely used in the treatment of diseases and conditions associated with the overproduction of oxidative radicals, such as wound healing,28 oral cavity inflammatory diseases,29, 30 cancer,31 periodontitis,32 and acute kidney injury.33 Recent studies have shown that, in combination with chlorhexidine digluconate (CHG) solution, CNPs significantly improve the antimicrobial properties of the composition.34 Nanoparticle-based treatment has become a prevalent practice in dentistry. Soundarajan and Rajasekar demonstrated that graphene oxide–silver nanocomposite mouthwash exhibited bactericidal and anti-inflammatory properties in the treatment of gingivitis.35

Our study aimed to evaluate the influence of local and systemic administration of CNPs on targeting oxidative stress activation in the oral cavity and on enhancing antioxidant properties of saliva in young individuals with obesity and generalized gingivitis.

Material and methods

Trial design

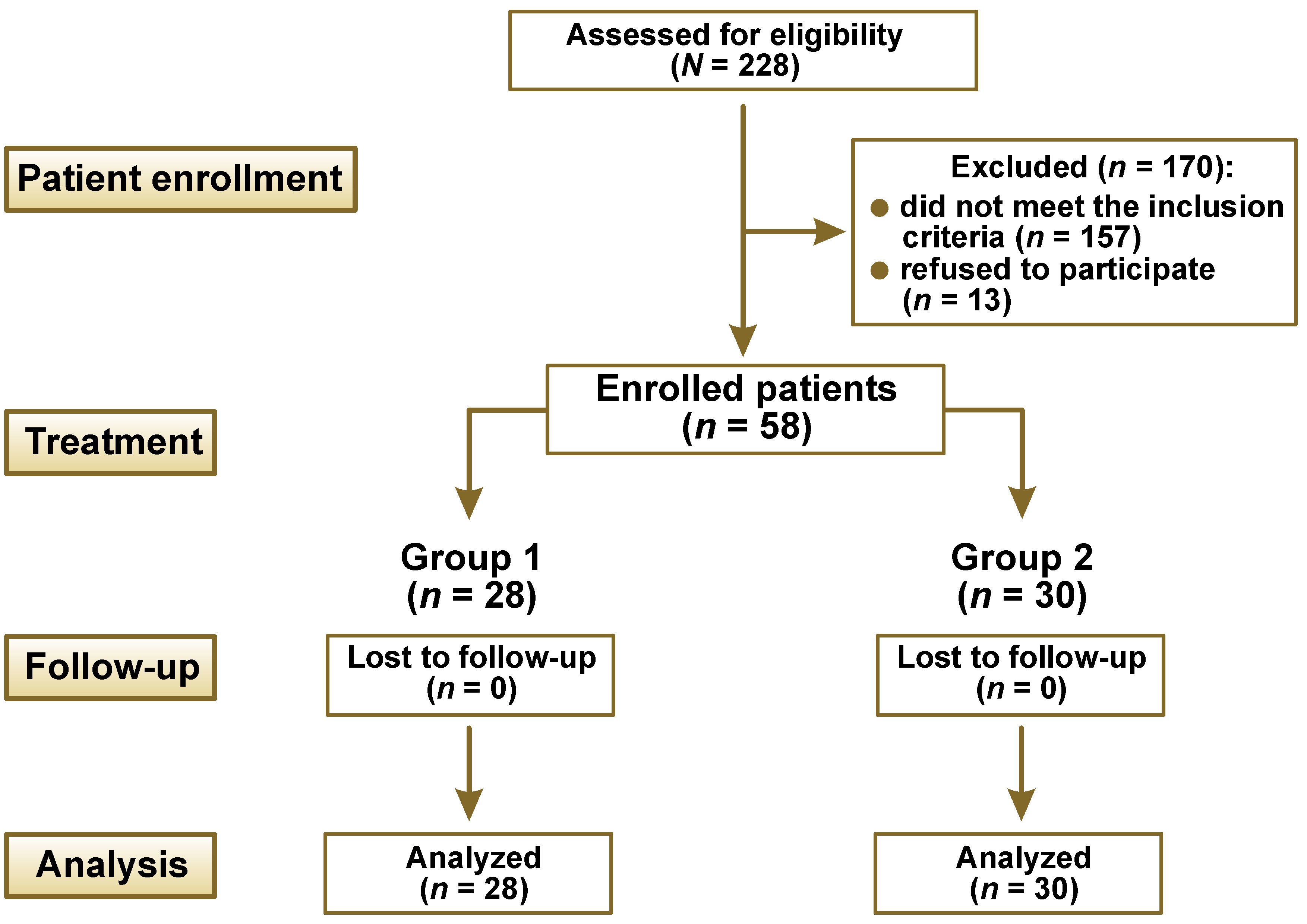

The randomized controlled, parallel clinical trial was conducted in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.36 Participants were allocated to groups using a randomized assignment process. The study design is presented in Figure 1.

Participants

The recruitment of patients was performed during the regular check-up of students. Before the study, all participants were informed about its design, purpose and possible risks. The eligibility criteria were as follows: young age (18–22 years); BMI of 30 kg/m2 and higher; Caucasian ethnicity; non-smoking status; absence of diagnosed endocrine and cardiovascular diseases; presence of at least 6 teeth per quadrant (excluding wisdom teeth); and a diagnosis of dental plaque-induced generalized gingivitis (mediated by the systemic risk factor of obesity), based on the 2017 Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions.10 The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, allergy to biguanides, the presence of removable or fixed prosthetic appliances or brackets, local dental plaque biofilm retention factors such as prominent restoration margins, and the use of antibiotics or antimicrobial mouthwashes during the preceding 3 months.

All participants were patients of the University Clinic of the Department of Therapeutic Dentistry at Poltava State Medical University in Ukraine. The data was collected from March 2021 to February 2022.

Interventions

The BMI measurements were used to determine the distribution of individuals into the treatment groups. Additionally, a full-mouth periodontal chart was completed for each participant. Two dentists (MSkr and TP) performed clinical measurement of periodontal parameters using the automated computer detecting system pa-on Parometer® (orangedental, Biberach, Germany). Furthermore, the Greene–Vermillion oral hygiene index (OHI), the approximal plaque index (API), the papillary-marginal-alveolar index (PMA), the papillary bleeding index (PBI), and clinical attachment loss (CAL) were considered.

The patients were randomly allocated into 2 groups. The first group (n = 28) received the treatment for dental plaque-induced gingivitis mediated by obesity, which entailed the following: complete removal of dental plaque and tartar via ultrasound scaling (Mini Piezon SA CH-1260; EMS Electro Medical Systems S.A., Nyon, Switzerland); polishing of the oral and vestibular teeth surfaces with an Enhance® finishing cup (Dentsply Sirona, Bensheim, Germany); and interproximal surface polishing with a narrow, fine grit polishing polyester strip (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The Nanosept solution, an antiseptic formulated for the local treatment of periodontal diseases (patent No. 139875, valid from January 27, 2020), was administered as a local antimicrobial treatment. The Nanosept solution is a 0.05% solution of CHG (Chervona Zirka, Kharkiv, Ukraine) and CNPs (2–7 nm), stabilized with sodium citrate, with a final concentration of 70 µg/mL. Subsequently, the oral hygiene Nanosept solution was applied to the gums with cotton sponges for 5 min. After treatment, the patients were instructed to apply the Nanosept solution twice a day (morning and evening) for 5 days after flossing and brushing their teeth, adhering to the same technique.

The second group (n = 30) underwent the same treatment as the first group, with the addition of the antioxidant Cerera (CNPs (2–7 nm), stabilized with sodium citrate). Cerera was prescribed as a general treatment for the patients, who were instructed to use it in the morning once a day by dissolving 20 drops of the antioxidant in 50 mL of drinking water for 10 days. For the purposes of this study, Cerera was synthesized and provided by MSp. The antioxidant was registered in Ukraine as a biological active supplement (registration No. TYY 10.8-2960512097-004:2015).

The follow-up period for periodontal treatment was established as 1 month. However, the participants were instructed to inform general practitioners (IS and RS) about adverse effects observed during the 9-month observation period after treatment. No adverse effects related to the provided treatment were reported.

Outcomes

The clinical data was recorded at the following time points: before treatment (T0); 7 days after treatment (T1); and 1 month after treatment (T2). For each patient, samples of the whole unstimulated saliva were collected at 2 time points: T0 and T1. The samples were procured during the morning hours, from 8.00 A.M. to 10.00 A.M. The whole saliva was collected into the test tube via passive drooling for 7 min. Then, the saliva was centrifuged for 5 min at 3,000 rpm. The supernatant was retrieved, divided into 1.0-mL aliquots and stored at −30°C until use. Oral swab samples for colonization resistance (CR) were obtained at T0 and T1.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated according to the recommendations for cross-sectional studies using the Sample Size Calculator (https://www.gigacalculator.com/calculators/power-sample-size-calculator.php). The minimum size of each group was calculated to be 29, with a 95% confidence interval (CI), type I error rate (α) of 5%, and a margin of error of 85%.

Patients were randomly allocated according to the random number table, employing the blocking type method with a block size of 4 and a range of numbers from 1 to 100. The table was designed by one of the researchers (MSki), who was not initially aware of the clinical trial design. After randomization, the sample comprised 12 male and 16 female subjects in the 1st group, and 16 male and 14 female participants in the 2nd group.

One researcher (KN) generated the random allocation sequence, 4 researchers (TP, MSkr, IS, and RS) enrolled participants, and 2 (TP and MSkr) assigned participants to interventions.

Analysis of salivary biomarkers

The determination of the free fucose content in the saliva of patients was performed according to the method designed by Sharaev et al.,37 based on the photometry of the chromogen that is formed under the sequential exposure of fucose to sulfuric acid and cysteine sulfate. The optical density of the samples was evaluated on a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 396 nm and 430 nm against blank samples. Then, the difference in extinction (E) between the experimental and standard samples (E = E396 – E430) was calculated and analyzed.

The content of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in the saliva was determined according to the method described by Sharaev et al.,38 which is based on the property of hexuronic acids to transform into furfural aldehyde or its homologues when heated with strong mineral acids, which results in their polymerization with carbazole. Photometry was performed at a wavelength of 530 nm against concentrated sulfuric acid containing 0.2 M of sodium tetraborate.

The determination of oxidatively modified proteins (OMPs) in the saliva of patients was performed according to the spectrophotometric method based on the quantitative analysis of carbonyl groups, which are formed during the interaction of reactive oxygen species with amino acid residues. The analysis uses 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine.39

The total activity of NOS was determined by observing the difference in the concentration of nitrite ions (NO2– before and after the incubation with saliva in a medium containing L-arginine (substrate of NOS) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP). The concentration of NO2– was determined by the formation of diazo compounds in the reaction with sulfanilic acid. Subsequently, the reaction with α-naphthylethylenediamine was carried out, which resulted in the formation of red derivatives (azo dyes).40 The intensity of the solution’s color is proportional to the concentration of nitrites.

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in saliva were evaluated according to the method outlined by Stalnaja and Garishvili.41 Upon heating with aldehydes, 2-thiobarbituric acid forms a trimethine complex, which exhibits a light absorption maximum at 532 nm. In this case, the intensity of the color of the solution was proportional to the concentration of TBARS.

The catalase activity in saliva was assessed according to the method described by Koroliuk et al.42 The reaction was initiated by adding saliva to 0.003% hydrogen peroxide solution. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 mL of 4% ammonium molybdate solution. The color intensity of the solution was determined at a wavelength of 410 nm.

The proteolytic activity of saliva was calculated based on the increase in free amino nitrogen, which is formed during the hydrolytic cleavage of protein substrates. Amino nitrogen yields a blue color in the reaction with ninhydrin. The color intensity is directly proportional to the content of free amino acids against the standard, which is glycine. The determination of proteinase inhibitors is based on the measurement of the difference between the activity of the test sample, which contains a certain amount of trypsin, and the activity of the sample with saliva.43

The activity of α-amylase in the saliva was measured using the α-amylase kit (Filisit-Diagnostika LLC, Dnipro, Ukraine) according to the Caraway method. In the presence of α-amylase, starch is hydrolyzed to derivatives that do not give a color in reaction with iodine. The change in the color intensity of the iodine–starch complex is proportional to the activity of the enzyme in the test sample.

The activity of nitrate and nitrite reductases in saliva was determined according to the method designed by Akimov and Kostenko.44 Enzyme activity was assessed based on the difference in the concentration of nitrites and nitrates before and after incubation of saliva in the aqueous solution of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). The concentration of nitrites was determined by the observation of the diazo compounds formed in the reaction with sulfanilic acid. The reaction was then carried out with α-naphthylamine (Griess–Ilosvay reagent). The color intensity of the red derivatives (azo dyes) is proportional to the nitrite concentration.

Colonization resistance of the oral mucosa

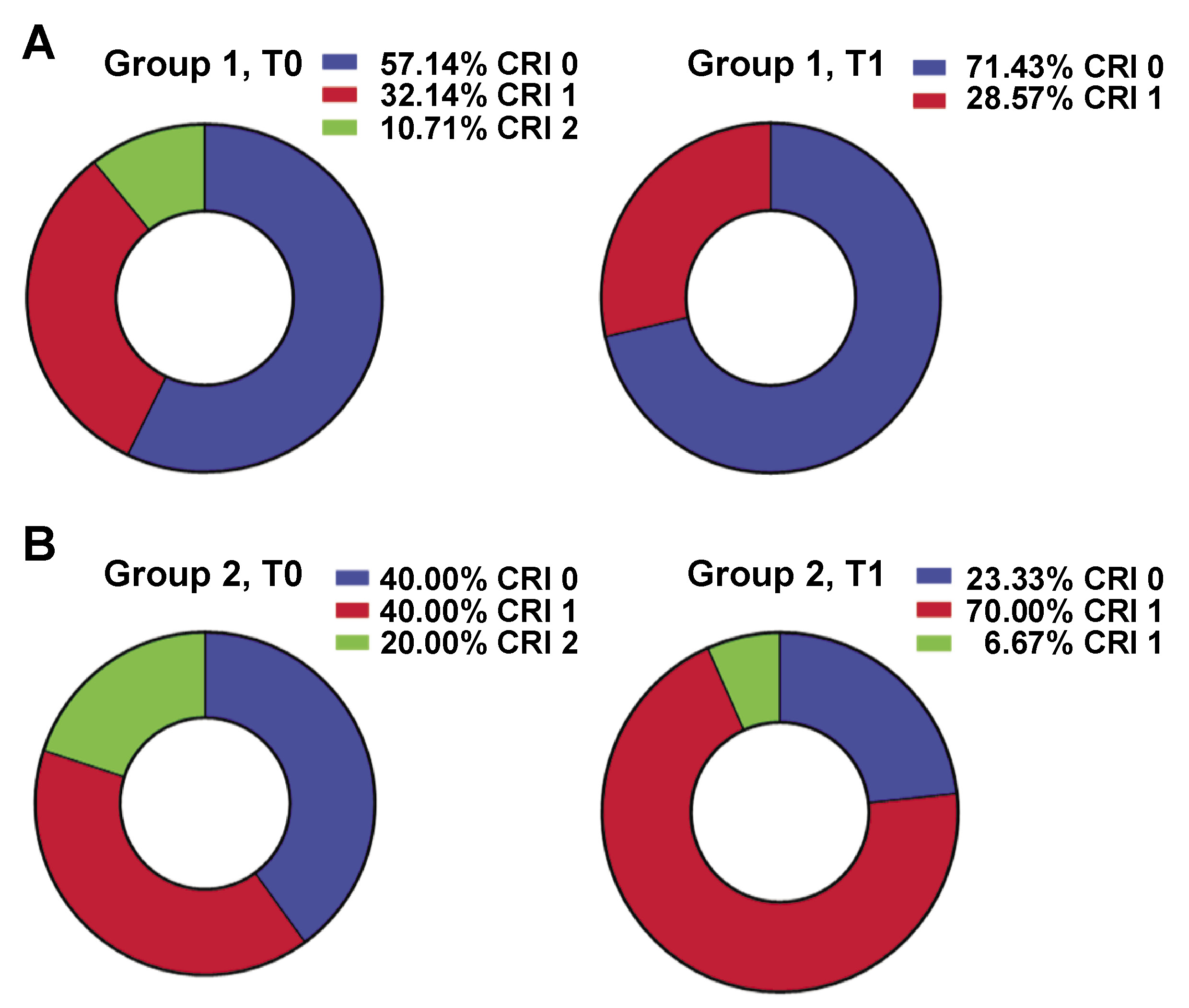

The degree of CR of the oral mucosa was determined by conducting a microscopical examination of the buccal epithelium. This method involves the determination of the adhesive number (AN) of streptococci adhered to 1 epitheliocyte, the adhesive index (AI) which quantifies the percentage of epitheliocytes that have more than 10 streptococci adhered, and a qualitative assessment of CR, denoted as the colonization resistance index (CRI). The AN < 20 and AI < 50% indicated the suppression of CR and reduced antagonistic properties of oral microflora. The CRI of 1, AN in the range of 20–60, and AI > 50% signified a high level of CR of the oral cavity, whereas the CRI of 2, AN > 60 and AI of 100% revealed an increased tension of the colonization barrier.45 The microscopic examination of the buccal epithelial samples was performed using a light microscope (Olympus CX23 RFS1; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at ×400 magnification.

Statistical analysis

The GraphPad Prism v. 8.0.1 software (GraphPad Software, Boston, USA) was used for the statistical analysis of the data. The results were described as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to process the data from unrelated samples, with Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons. Paired comparisons within a group, before and after treatment, were conducted using Student’s paired t-test. To analyze statistical differences between different groups, an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was used. The differences between the groups were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Clinical evaluation of oral hygiene level and the intensity of inflammation in the periodontium

In both groups, the initial level of oral hygiene (T0), as determined by OHI, was assessed as average. However, the API-based evaluation of the hygiene of the approximal surfaces revealed suboptimal conditions in both groups. The oral bleeding indexes that reflect the severity of inflammation (PMA and PBI) were high, indicating the presence of gingivitis, while no CAL was reported. One week after treatment (T1), the normalization of oral hygiene and the resolution of gingivitis were observed in both groups. A significant decrease in OHI, PMA and PBI was documented. After 1 month (T2), no signs of gingivitis were registered; however, plaque accumulation was high on the vestibular (OHI) and interproximal surfaces (API) (Table 1).

Changes in the colonization resistance of the oral cavity

Before treatment (T0), CRI values of 1 and 0 prevailed in both groups (Figure 2). After treatment (T1), the majority of patients in group 1 exhibited CRI of 0 (71.43%), while the remaining individuals demonstrated CRI of 1 (Figure 2A). However, in group 2, the value of 1 was predominant (70.00%) after treatment, with CRI of 0 being observed in 23.33% of the participants (Figure 2B). Before treatment, AI and AN in the first group were 18.25 ±14.81 and 67.00 ±31.65, respectively, and in the second group, 19.54 ±12.53 and 64.67 ±32.81, respectively. After the treatment, a statistically significant change in AN was observed in both groups (38.96 ±37.98 and 39.23 ±33.63 in group 1 and 2, respectively; p < 0.01). However, changes in AI were not significant (17.46 ±14.09 and 23.21 ±19.33, respectively). After treatment (T1), no differences in AI and AN were noted between the 2 groups.

Changes in salivary biomarkers

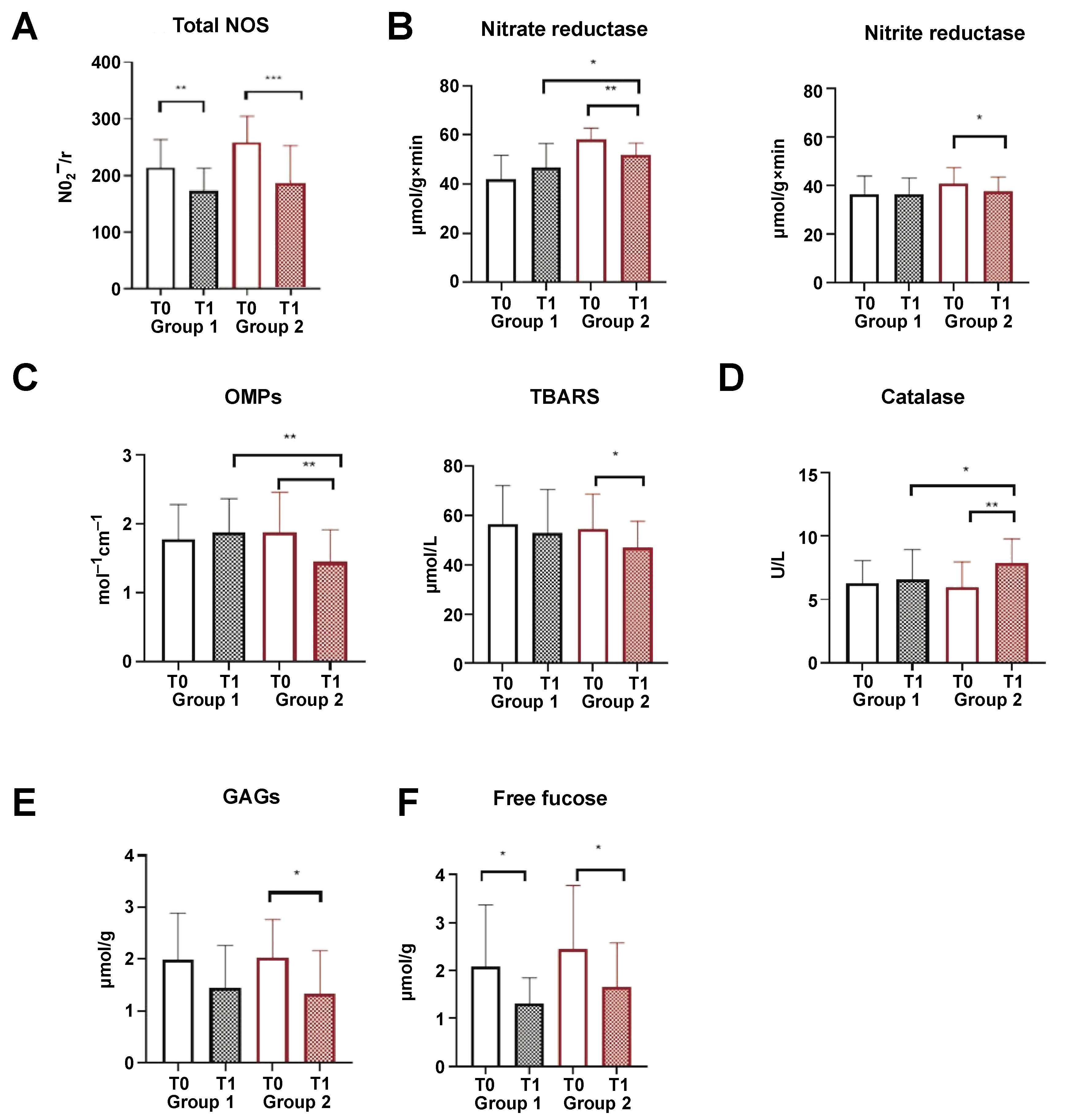

In both groups, treatment resulted in a significant decrease in total NOS activity and free fucose concentration (Figure 3A,F). There was no change in the levels of salivary α-amylase activity, total proteolytic activity and proteinase inhibitors, as well as the concentration of nitrites and nitrates in saliva (supplementary materials – available on request from the corresponding author). In the saliva of the patients from group 2, a slight yet significant decrease in nitrate and nitrite reductase was observed (Figure 3B). A significant reduction in markers of oxidative stress, such as OMPs and TBARS, and an increase in catalase activity was detected in group 2 (Figure 3C). A significant decline in GAG concentration was documented in group 2; however, a tendency toward a decrease in GAG concentration was also observed in group 1 (Figure 3D).

During the observation period, no side effects of the proposed treatment were reported.

Discussion

Clinical findings

Our findings demonstrate that local treatment with the Nanosept solution, which is a combination of CNPs and CHG, and complex treatment that included a systemic application of CNPs resulted in a complete resolution of gingivitis in both groups. The results of treatment were stable up to 1 month of observation (Table 1). Oral hygiene indexes (OHI, API) returned to their initial state 1 month after treatment; however, no gingivitis was observed. The outcomes of recent observational studies have shown that frequent toothbrushing was negatively associated with BMI.46, 47

Colonization resistance of the oral cavity

Colonization resistance (bacterial interference) is the local mechanism of the oral cavity’s unspecific immunity. It provides individual specificity and stability for the adhesion and growth of pathogen bacteria on host oral mucosae. A certain role in this process can be attributed to resident bacteria, which act as antagonists to pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria.48 The antagonistic effect of microflora physiology is facilitated by the significant adhesive and colonizing capabilities of resident bacteria, as well as the production of specific substances, including bacteriocins and antibiotics, which suppress the growth of pathogenic microorganisms.49, 50 Several factors have an influence on CR, such as hyposalivation, changes in the qualitative composition of saliva, smoking, tobacco chewing, high sugar consumption, immunosuppression, or acidic pH.51

Decreased CR can lead to bacterial invasion of underlying tissues and the subsequent development of purulent-inflammatory processes.52 Thus, germ-free animals, which lack an indigenous microbiome after transient bacterial exposure, developed intestinal walls, villi malfunction, poor nutrient absorption, vitamin deficiencies, and cecum enlargement.53 Streptococcus species are the most prevalent microorganisms in the oral cavity and play an important role in establishing and shaping the oral microbiome.54

In group 1, where CNP and CHG solution was applied locally, a decrease in CR tension was observed. Patients with CRI of 2 were not registered after treatment, and CRI of 0 was predominant in the group. This finding indicates the suppression of CR and reduced antagonistic properties of oral microflora (Figure 2A). The adhesive number decreased significantly in group 1, indicating a reduction in CR and the total microbial load of the oral mucosa. In group 2, where CNPs were applied locally and administered intraorally after treatment, CRI values of 1 prevailed among subjects, indicating a high level of CR of the oral cavity (Figure 2B). However, approx. 30% of patients exhibited CRI of 0 after treatment, which was a sign of suppressed CR, and CRI of 2, which indicated an increased tension of the colonization barrier. Thus, systemic administration of CNPs led to an increase in CR of the oral mucosa in obese subjects with gingivitis, in comparison to group 1 where only local administration of CNPs and CHG was implemented. A significant reduction in total AN was observed following treatment in both groups, which can be attributable to high antimicrobial activity of CNP and CHG composition. However, the precise mechanism underlying the increase in CR after systemic administration of CNPs remains unclear.

Reduction in oxidative and nitrosative stress after systemic administration of CNPs

Periodontal tissue damage, determined through oxidative and nitrosative stress, has been identified as an important mechanism in the development of periodontitis, especially in patients with obesity.15, 18, 19, 21 Nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) reductase, vital enzymes within the nitrate–nitrite–NO pathway, facilitate NOS and subsequent vasodilation. These enzymes act as substrates for the synthesis of NO under physiological conditions or in response to hypoxia, inflammation and diseases involving ischemia–reperfusion injury.55 Oral cavity bacteria, predominantly those located at the back of the tongue, also play a significant role in the conversion of NO3− and NO2− to NO in the human body. Up to 25% of nitrate in circulation is excreted by salivary glands, resulting in a 20-fold increase in its concentration in saliva.56 The activity of nitrate and nitrite reductase and NO as their end product significantly increases in patients with periodontitis.57 High activity of iNOS in saliva and periodontal tissues is a marker of periodontitis, and it is much higher in patients with aggressive periodontitis.23, 58 Excessive activation of iNOS (mostly by mast cells and lymphocytes)23 as well as nitrate and nitrite reductases in obese individuals can be described as a compensatory reaction to hypoxia that leads to NOS and vessel dilatation.15 Hyperproduction of NO causes nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation that triggers the synthesis of systemic inflammatory response cytokines. A reaction of NO with superoxide anion radical results in ONOO− formation and free radical cell damage, necrobiosis, and premature aging. Xu et al. and Hou et al. reported that CNPs decrease the nitrate reductase activity in bacterial biofilms.59, 60 Cerium nanoparticles convert both superoxide (O2−) and H2O2 into more inert species, while also scavenging NO both in vitro and in vivo, significantly accelerating the decay of ONOO−.61

A significant decrease in total salivary NOS levels was observed after treatment in both groups (p < 0.01 in group 1 and p < 0.001 in group 2) (Figure 3A). The activity of nitrite and nitrate reductases decreased only after peroral administration of CNPs (group 2). The nitrate reductase activity following treatment was significantly higher in group 2 compared to group 1 (p < 0.05), which might stem from the higher initial activity of this enzyme in group 2 (Figure 3B). The concentration of the substrate (nitrites and nitrates) remained constant before and after treatment in both groups.

The total concentration of biomarkers of oxidative stress, TBARS and OMPs, decreased significantly only after systemic administration of CNPs (group 2) (Figure 3C). In group 2, a significant increase in catalase activity was observed (p < 0.01) (Figure 3D). The concentration of OMPs in group 2 was significantly lower than that in group 1 (p < 0.01) (Figure 3C). Additionally, a notable increase in catalase activity was observed in group 2 following treatment (p < 0.05) (Figure 3D). The inhibition of oxidative stress and an increase in the antioxidative capacity of saliva after the intraoral administration of CNPs can be attributed to the CNP catalase activity and superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic activity.62, 63 However, local application of CNPs (group 1) did not result in the suppression of oxidative stress.

Glycosaminoglycans (dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate, keratan sulfate, and creatine) are components of the connective tissue extracellular matrix. A high concentration of GAGs in saliva has been associated with inflammatory periodontal diseases, oxidative and nitrative stress activation, mucositis, wound healing, and ageing.64, 65, 66, 67 Periodontopathogens, such as Tannerella forsythia, secrete sialidases that enzymatically digest the mucopolysaccharides present in the gingival extracellular matrix. This process leads to the release of GAGs, which promotes further bacterial colonization and the development of the climax biofilm.68, 69 In the current study, the concentration of GAGs in saliva decreased after treatment in both groups (Figure 3E), which can be attributed to the complete resolution of gingivitis and oral hygiene improvement.

An increase in the free fucose concentration in saliva is associated with oral mucosa and gingiva inflammation. Free fucose is released through the hydrolytic activity of pathogens and indigenous bacteria.70, 71 High salivary free fucose levels create favorable conditions for the colonization of opportunistic bacteria, which can utilize it as an energy source.71

In both groups, treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the salivary fucose and GAG concentrations, consequently leading to a reduction in CR tension (Figure 3E,F).

Patients suffering from obesity and periodontal diseases should receive local traditional non-surgical treatment for gingivitis as well as pharmaceutical treatment, which will target the pathogenesis of both periodontal disease and obesity. This would mediate host immune response and result in a more severe course of gingivitis. It is important to stop the progression of gingivitis and prevent irreversible changes such as alveolar bone loss or CAL, which effectively contribute to the paradigm shift from reactive medicine to the advanced approach by utilizing predictive, preventive and personalized medicine (3PM) concepts.72

Limitations

A limitation of the study is the inability to control the regularity, proper duration and performance of all prescribed treatment procedures performed by patients at home. Another constraint is a relatively short post-treatment periodontal observation period (1 month). However, a 9-month observation period was established to monitor for any side effects that may have ensued from the treatment.

A group of patients receiving standard gingivitis treatment and a second group receiving local chlorhexidine application in addition to the standard treatment may be suitable subjects for this study. However, establishing two additional groups would have required recruiting more patients. This proved unfeasible, as all available participants were medical students from our university. In order to ensure the unification of environmental factors and lifestyles, we decided not to recruit participants who were not medical students at Poltava State Medical University. The severity (percentage of affected sites) and location of inflammatory sites of generalized gingivitis exhibited variability among all patients. The study participants comprised medical and dental students. It is noteworthy that the participants’ enrollment in the clinical study occurred in close temporal proximity to their examination session. This period is associated with elevated academic stress, which has been demonstrated to cause the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, oxidative stress and gingivitis.

Conclusions

Both local (CNPs and CHG) and complex treatment resulted in a complete resolution of generalized gingivitis. In both groups, a significant reduction in AN of oral streptococci on the buccal epithelium was observed. After the local treatment with CNPs, a decline in CR was observed in group 1. However, the combination of local and systemic CNP administration resulted in a restoration of the normal level of CR. Both treatment modalities led to a decrease in salivary free fucose and GAG concentration, which are the markers of oral mucosa and gingiva inflammation, and as a substrate can contribute to extensive colonization of the oral cavity with opportunistic bacteria. The total NOS activity significantly decreased in both groups. Yet, a significant reduction in nitrite and nitrate reductases was observed only after the intraoral administration of CNPs. This was accompanied by a significant reduction in salivary oxidative stress biomarkers (OMPs and TBARS) and a significant increase in salivary catalase activity. In comparison with the local treatment alone, systemic administration of CNPs resulted in a significant increase in salivary catalase activity and a decrease in OMP level in saliva after treatment.

Therefore, as an antioxidant, CNPs can be used for the complex treatment and prevention of periodontal diseases, especially in patients with predisposed conditions associated with oxidate and nitrosative stress activation, such as obesity.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The clinical trial design was approved by the Committee on Ethical Issues and Biomedical Ethics of Poltava State Medical University, Ukraine (approval No. 197). All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and Ukrainian national research committees (statement of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine No. 690 revised in 2009) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.