Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) shows significant potential in supporting development and management in everyday dental practice; however, significant challenges, limitations and uncertainties remain.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, AI, dentistry, medicine

Introduction

The modern world – including the field of medical sciences – is steadily advancing toward greater automation and computerization of procedures. This shift affects all aspects of clinical and laboratory workflows, from the use of three-dimensional (3D) printing in material sciences to the application of computer systems for obtaining and analyzing various types of information.1, 2, 3 Artificial intelligence (AI) is a tool increasingly used across many fields today. First described in the 1950s, it initially referred to mechanical devices, but it soon evolved into a central focus of interest across numerous domains of modern society. Although AI continues to advance rapidly and is becoming more familiar to the general public, concerns persist regarding its potential to replace human thinking and intelligence.

The healthcare industry increasingly integrates AI, moving toward a future in which certain aspects of care may be partially driven by robots and advanced medical devices, reducing the need for direct human involvement. Through its capacity for machine learning and large-scale data analysis, AI has already begun to revolutionize many areas of medicine, including dentistry. A major focus in these fields is the transition from manual, clinician-dependent processes to more predictable, computer-assisted tools. Such technologies have potential to enhance diagnosis, treatment planning and the overall management of oral health. Since many clinical patterns are repetitive, computer systems can ‘learn’ to recognize similarities between conditions, which can be especially valuable in diagnosing non-specific orofacial diseases. With these learning capabilities, AI can also replicate effective treatment patterns, potentially leading to more accurate and precise procedures across all disciplines of dentistry.4, 5

Artificial intelligence appears to offer valuable support for less experienced practitioners, enhancing their diagnostic and clinical decision-making capabilities. However, important questions remain: Is AI a reliable solution in all cases, and could it ultimately replace human intellect and clinical judgment? Are ethical considerations being adequately addressed, and how is data privacy ensured? As AI continues to evolve, the central debate persists – will it serve primarily as a supportive tool for clinicians, or could it eventually challenge or even substitute their roles?

Advantages of AI in dentistry

Enhancing diagnostic accuracy

The advantages of using AI in dentistry are widely discussed, particularly in relation to diagnostic accuracy and clinical efficiency. Artificial intelligence – especially systems based on deep learning – has demonstrated the ability to outperform conventional methods in detecting caries, periodontal diseases, and even more serious conditions requiring surgical intervention, such as oral cancers.

The mathematical models incorporating techniques like fractal dimension and texture analysis make it increasingly feasible to assess bone quality and the condition of the oral mucosa, using less invasive tools, such as two-dimensional (2D) radiographs and clinical photographs.6, 7 In this context, imaging data can serve as a valuable resource for identifying pathological changes and monitoring their progression.8 For more advanced radiographic interpretation, particularly of 3D imaging modalities, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have proven especially useful. They currently offer the highest accuracy in tasks such as tooth segmentation, classification and categorization.9

In addition to supporting the diagnosis of bone and oral mucosa conditions, AI can also assist with color management in restorative and prosthetic dentistry. Since human vision is not always reliable for selecting accurate shades, AI-based systems may provide more consistent and objective color-matching results.10

However, despite these advantages, human oversight remains essential. AI-generated recommendations should be viewed as supportive guidance rather than definitive decisions. The same principle applies to treatment planning, where AI can offer valuable insights, but cannot replace the clinician’s expertise and judgment.

Treatment planning

The need for advanced treatment planning is particularly evident in surgery, prosthodontics and orthodontics. These specialties often require not only visualization tools, but also treatment simulations that can illustrate the anticipated outcomes of various procedures.

In orthodontics, for example, modern aligner systems rely heavily on AI-driven design to generate sequential tooth movements. Cephalometric analysis – an essential component of both orthodontic and orthognathic treatment planning – can also be enhanced through AI-based automated landmark identification and measurement.11 Although AI-supported aligner planning appears highly precise, real-world clinical outcomes often deviate from the initial digital prediction. Consequently, additional refinements and mid-course corrections are frequently needed to achieve the desired final result.

Artificial intelligence can also play a significant role in planning various surgical and prosthetic procedures, including implant placement and bite reconstruction. Such planning is particularly critical in the anterior maxilla, where both functional and esthetic demands are high. Clinicians must anticipate not only the precise positioning of the implant, but also the morphology and placement of the future prosthetic crown or bridge to ensure an optimal esthetic and functional outcome.12 AI-based tools can further assist by identifying key anatomical structures, such as the inferior alveolar canal, thereby improving the safety and accuracy of surgical procedures.13 As previously noted, AI can also aid in the detection of oral pathologies, including cancers. The early identification facilitated by AI may significantly shorten the time between diagnosis and surgical intervention, ultimately improving patient outcomes.4, 5

Patient communication

Artificial intelligence can be highly valuable in preparing standardized information for patients, supporting more efficient dental practice management. It can assist in creating educational content about treatment and procedures, including real-time responses to patient questions via chatbots. Natural language processing (NLP) technologies further enhance these capabilities, enabling automated appointment scheduling, check-up reminders and follow-ups – tasks that can now be handled without human intervention, with significantly improved efficiency.14 Additionally, AI could assist in ‘pre-triage’ procedures, helping to prioritize patients based on the urgency of their condition.

However, a key limitation remains the lack of human oversight over the information provided, especially in response to frequently asked questions (FAQs). Despite this, the most practical current application of AI may be in reducing the clinician’s time spent answering routine questions and assisting with patient anamnesis in a safe, non-intrusive way.

Critical management

Although AI offers numerous advantages, it is also associated with potential errors and inaccuracies that must be carefully considered. Only through critical oversight, with a human expert supervising its use, can AI provide reliable and unbiased information or results.

Data quality and bias

AI systems can exhibit significant bias, as their outputs are limited to the data on which they are trained. This means that important information may be overlooked, and the data presented may lack diversity, being restricted to certain ethnic groups, genders, ages, or socioeconomic backgrounds. AI models are generally not equipped to critically evaluate the limitations of their datasets, which can result in biased outputs being interpreted as definitive results.

This issue is particularly important in healthcare, including dentistry, where biased AI recommendations can affect diagnosis, treatment planning and other clinical decisions, potentially exacerbating the existing disparities. Moreover, such bias complicates the development of standardized medical protocols, as algorithmic evaluations remain far from perfect. This challenge represents a broader, unresolved problem in medicine, which may even be amplified by AI. While more advanced tools could potentially mitigate these problems in the future, significant further development of AI itself is required to achieve this goal.

Clinical integration, ethical and legal considerations

The use of AI in clinical diagnosis and procedures, particularly in surgery, carries significant implications. The reliability of AI remains uncertain, raising concerns about potential “secondary dumbness,” where overreliance on AI could deskill clinicians and diminish their ability to make independent decisions. This poses a direct risk to patient safety, especially in surgical contexts, where rapid, informed action is often critical. In addition, AI systems are susceptible to bias, which increases the likelihood of errors in their outputs.

Data privacy is another key concern, as training commercial AI systems requires explicit patient consent. This includes not only personal information, but also medical images (e.g., X-rays) and laboratory results, such as blood tests.

Another critical issue is accountability in the use of AI. If an AI system provides an incorrect diagnosis or recommends an inappropriate treatment plan, who bears responsibility for the error? Artificial intelligence itself cannot be held accountable, raising complex questions about whether liability falls on the developer, the information technology (IT) specialist, the clinician, or the healthcare institution. Ethical and legal frameworks are therefore essential for the responsible implementation of AI in clinical practice.

It is equally important to emphasize that all AI-generated recommendations must be reviewed by a human professional. In this context, AI should be regarded as a supportive tool to assist clinicians, rather than as a replacement for human judgment in diagnosis and treatment.

Cost and accessibility

In addition to the limitations already discussed, the adoption of AI in dentistry may be constrained by cost considerations. Implementing AI requires standardized systems, including specialized hardware and software, which can be expensive. This financial barrier may limit adoption, particularly in smaller dental practices or in rural areas. Furthermore, some clinicians may face challenges in learning and integrating these new technologies, potentially widening the disparities among dental care providers.

These issues also raise important ethical questions regarding the equitable use of advanced AI tools in resource-limited settings, including parts of Africa and other low-income regions.

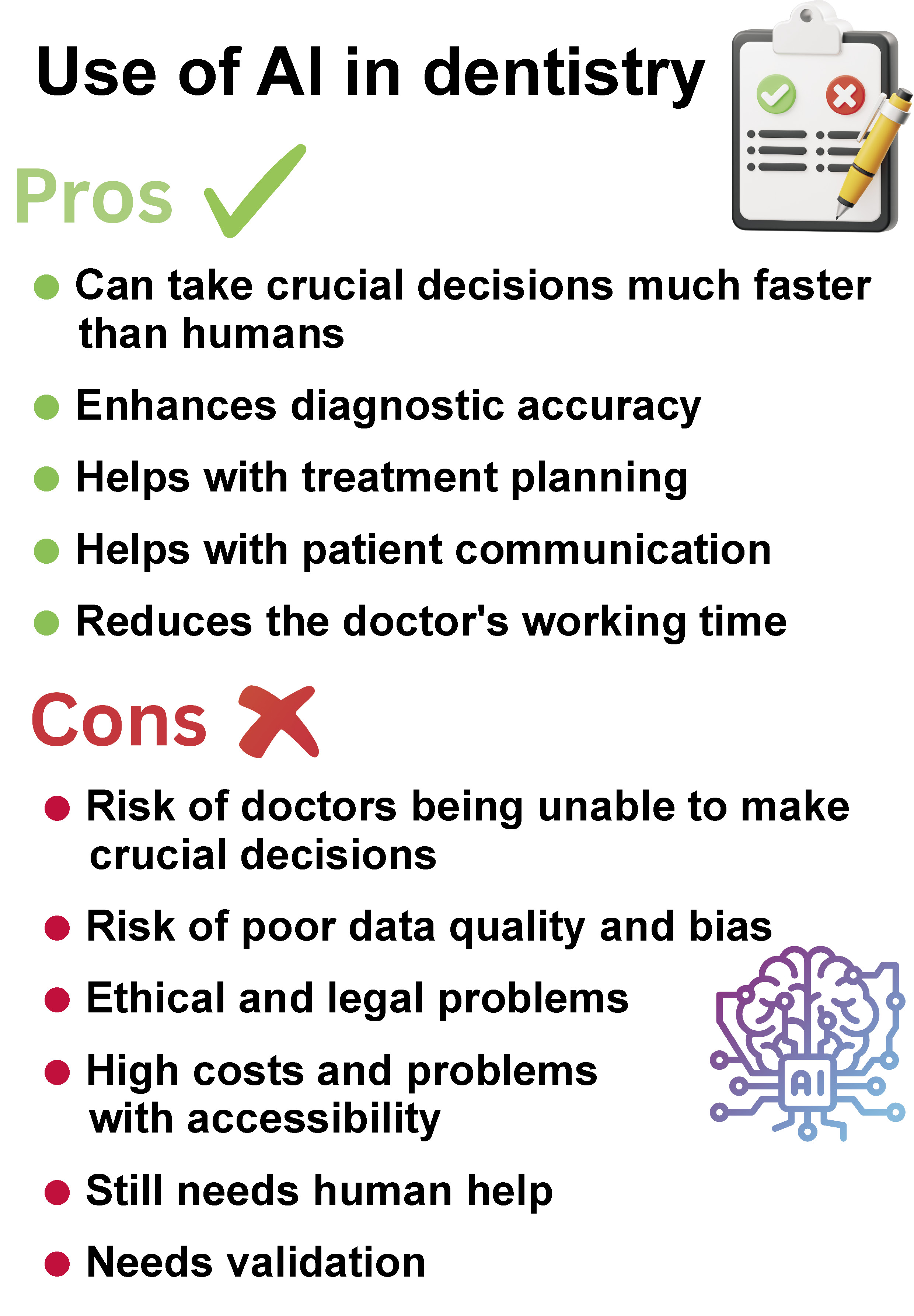

Figure 1 summarizes the key advantages and disadvantages of AI in healthcare. In the author’s view, many critical questions must be addressed before AI can be fully integrated into medical practice.

Future perspectives and conclusions

The future of AI, while promising, remains uncertain. Several challenges must be addressed before AI can be widely implemented in everyday medical and dental practice. Clear guidelines, as well as the rigorous validation and standardization of these tools are essential prior to their full integration. Ideally, AI should serve as a clinical adjunct rather than a replacement for human expertise.

Ethical and legal frameworks also require development to ensure safe and responsible use. While AI has potential to support clinicians, including dentists, in daily practice, it is important to remain aware of its limitations and maintain a critical perspective, particularly given that human health and well-being are at stake.

Some limitations are not inherent to the technology itself but stem from clinicians’ understanding of AI. Deep learning-based algorithms, for example, can be difficult to interpret, which may complicate the justification of clinical decisions. This challenge has been highlighted by Razdan et al.,15 underscoring the need for proper training and awareness among dental professionals.

The high expectations for AI may take time to be fully realized, if they are achievable at all. While AI holds significant potential to improve diagnostic accuracy, issues of bias and ethical transparency must be addressed. Substantial development is still required in these areas, particularly regarding clinical reliability and ethical oversight.

A key concern is whether reliance on AI could inadvertently reduce the quality of care, leading to a routine, ‘mindless’ approach to diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, as diseases and treatment protocols are constantly evolving, AI systems must be capable of ongoing retraining to recognize new conditions, the emerging symptoms and the updated therapeutic approaches. Medicine teaches us that routine can be a significant risk, so strategies must be implemented to prevent overreliance on automated processes.

At present, AI cannot yet serve as a clinical standard, but it undeniably represents a critical component of the future of medicine.

In summary, AI shows considerable potential for improving development and management in everyday dental practice; however, significant challenges, limitations and uncertainties remain.