Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, systemic disease with complex and unclear pathogenesis, primarily affecting the gastrointestinal tract. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with a wide spectrum of extraintestinal complications, among which cancer is of particular importance. It is well known that IBD is associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). Yet, the incidence of CRC in this group of patients has decreased due to the development of surveillance techniques and therapy. In contrast, the relationship between IBD and extraintestinal malignancies (EMs) remains unclear, and it is taking on new significance in light of the rise in the incidence of malignant tumors, both in IBD patients and in the general population. Based on the literature review, it can be stated that the available studies suggest a possible association between IBD and oral, pancreatic and hepatobiliary malignancies. However, the dynamic epidemiological situation, combined with the methodological limitations of many existing studies, underscores the need for further research to better understand the relationship between IBD and cancer. In this group of patients, special oncological vigilance, the employment of the available prevention methods (e.g., vaccination), patient education, and, when recommended, screening tests are required. A clinical challenge involving a multidisciplinary approach is the treatment of IBD in cancer patients, especially during disease exacerbation, as well as cancer therapy in IBD patients.

Keywords: inflammation, neoplasms, inflammatory bowel disease, immunosuppression therapy

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), encompassing Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic disease of complex and unclear etiology. It is assumed that in genetically predisposed individuals, environmental factors, such as impaired intestinal permeability and dysbiosis, lead to the dysregulation of the immune system and chronic intestinal inflammation. Inflammation can affect other organs, leading to extraintestinal manifestations in IBD patients.1

Currently, nearly 3.9 million females and 3.0 million males are living with IBD worldwide, and a considerable rise in both incidence and prevalence of IBD has been observed. Inflammatory bowel disease is an incurable disease with a difficult-to-predict course, and cancer is the second most common cause of death for IBD patients after cardiovascular disease.2, 3

Many researchers are striving to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying cancer development in patients with IBD, which are gradually becoming better understood. Most scientific studies focus on colorectal cancer (CRC). In their recent study, Hisamatsu et al. found that chronic inflammation in IBD promotes tumor development by activating several key pathways, including NF-κB, JAK/STAT and Wnt/β-catenin, which drive cell proliferation and survival.4 In addition to neoplastic transformation via DNA damage, the oxidative stress caused by chronic inflammation is also an important factor inducing the mutations and chromosomal instability required for cancer progression. Advances in epigenetics, in turn, have shown that CpG island hypermethylation and mismatch repair defects contribute to early carcinogenesis in colitis-induced cancer.4 Chronic inflammation due to IBD results in systemic immune activation and epithelial damage, which may promote carcinogenesis not only in the colon, but also across many organ systems. Immunosuppressive therapies predispose to immune deregulation, leading to an enhanced risk for virus-related malignancies (e.g., lymphoma) and skin cancers. Additionally, continuous inflammatory signals and cytokine imbalance may lead to the formation of an in vivo microenvironment for malignancies beyond the gut mucosa, contributing to an increased incidence of cholangiocarcinoma (CCa)/urothelial carcinoma. This seems to imply that a set of both iatrogenic and intrinsic immune pathologies can be postulated as drivers of a systemic cancer risk in IBD patients.5

Another relevant factor is the influence of gut microbiota disorders on the process of carcinogenesis. Minervini et al. in their review showed that gut dysbiosis, or the imbalance of gut microbiota, promotes the process of carcinogenesis due to the production of toxins that have a harmful effect on the genome, the induction of inflammation and the disruption of the host immune response.6 Bacteria that exert a harmful effect include Fusobacterium nucleatum, Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis. These microorganisms, by weakening the host immune response, may allow cancer cells to evade elimination by the immune system.6

Banthia et al. in their review indicate that there is an association between periodontal disease and an increased risk of cancer, especially in the case of head and neck, esophageal, lung, and gastrointestinal cancers.7 However, the researchers present no evidence of an association between periodontal disease and the risk of metastasis in already diagnosed cancers. It is important to remember that chronic inflammation and the changes in the oral microbiome involving specific pathogens may promote cancer development.7

Patients with IBD are at significantly increased risk of CRC, mainly due to the pro-neoplastic effects of chronic intestinal inflammation. The most important risk factors for CRC in IBD patients are the duration of the disease, its extent and severity, the presence of post-inflammatory pseudopolyps, the coexistence of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and a family history of CRC.8, 9, 10 The worldwide incidence rate of CRC in CD is estimated to be between 19.5 and 344.9/100,000 per year, and between 54.5 and 543.5/100,000 per year in patients with UC.11 It is estimated that in the cases of long-standing UC and Crohn’s colitis (except for proctitis), there is a 2–3-fold increased risk of CRC as compared to the general population. Nevertheless, the available studies indicate that the rates of CRC in IBD are decreasing over time, likely due to improved medical therapies and endoscopic surveillance.

In contrast, the link between IBD and extraintestinal malignancies (EMs) remains unclear. In general, the incidence of malignant tumors is on the rise, both in the general population and in patients with IBD. The treatment of patients with IBD has advanced with the introduction of novel therapies. However, it is important to note the increased risk of cancer associated with immunosuppressive treatment.

Our review is innovative, since it is one of the few that focus on the association between IBD and the risk of less frequently discussed EMs. The review aims to summarize the available data and identify potential pathophysiological mechanisms that may link chronic inflammation to the development of malignancies at sites remote from the gut. Analyses such as ours may contribute to better identification of risk groups and the development of more effective cancer surveillance strategies in patients with IBD. The present review explores the relationship between IBD and EMs, including their characteristics and risk factors. Understanding these associations may help inform clinical decision-making and improve cancer surveillance in patients with IBD.

Material and methods

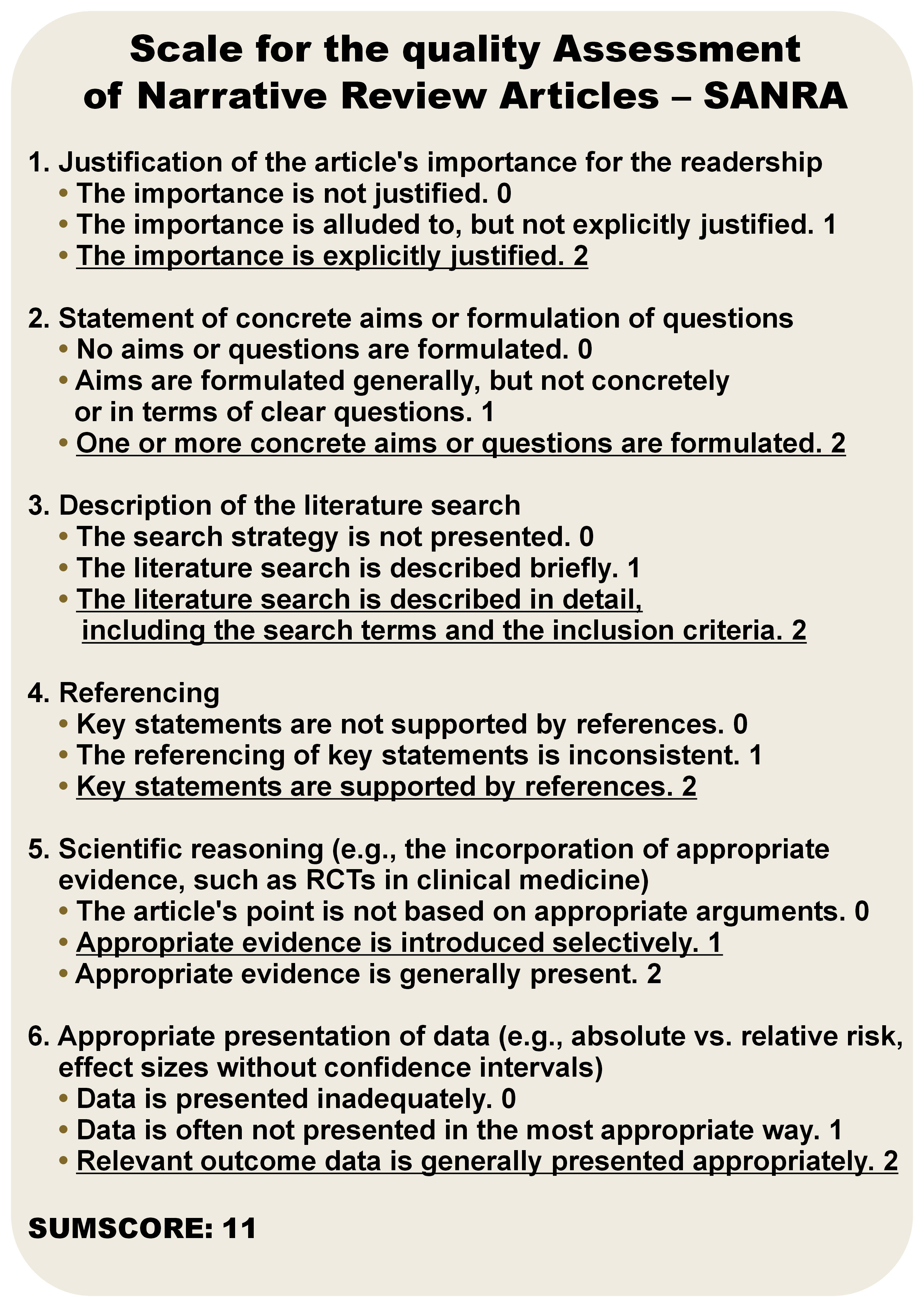

The literature search was performed in the Embase and PubMed databases, using the combinations of the following keywords: (“cancer*” OR “malignancy*” OR “tumor*” AND “Crohn’s disease” OR “ulcerative colitis” OR “inflammatory bowel disease*” OR “IBD”). The search was limited to the articles published between January 2015 and August 2024. The asterisks allowed us to retrieve records where the query words appeared with suffixes. The exclusion criteria were as follows: experimental studies (including animal studies and in vitro research); non-IBD studies; studies solely on CRC; non-original articles; non-English language; abstracts; and posters. The evidence-based medicine (EBM) pyramid was used to assess the quality of the studies.12 This narrative review followed the Scale for the quality Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) criteria and the SANRA score for the review is presented in Figure 1.13

Results

We found 39 studies that examined the link between EMs and IBD, along with 20 studies on the connection between EMs and IBD treatment, that met the inclusion criteria.

We systematized the search results according to the location of the tumor: oral, head and neck cancers; thyroid cancer (TC); lung cancer (LC); breast cancer (BC); pancreatic cancer (PC); hepatobiliary cancer; urinary tract cancer; prostate cancer (PCa); reproductive system cancers; central nervous system malignancies; hematological malignancies; and skin cancers.

Inflammatory bowel diseases and oral, head and neck cancers

Most head and neck cancers (HNC) originate from the mucosal epithelium of the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx, and are known as head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Cancers of the oral cavity and larynx are generally linked to tobacco consumption, alcohol abuse, or both, while pharynx cancers are increasingly associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, primarily HPV-16.14

The relationship between IBD and an increased risk of oral cancer has been the subject of many studies. In IBD, disturbances occur not only in the gut microbiome, but also in the oral microbiome.15, 16 The resulting dysbiosis contributes to an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to the development of periodontitis.17, 18 The presence of chronic inflammation promotes oxidative stress and DNA damage, which increases the risk of the neoplastic transformation of oral epithelial cells. It should also be noted that patients with IBD undergoing immunosuppressive therapy are at increased risk of developing dysplastic lesions in the oral cavity. Immunosuppression weakens the body’s natural immune defense mechanisms, reducing the ability to eliminate cells with tumorigenic potential, while simultaneously increasing susceptibility to HPV infection, a key risk factor for the development of oral cancer.19, 20, 21

We identified 6 studies examining the association between IBD and cancers of the oral cavity, head and neck (Table 1).20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 The results of all the studies, including a recently published Mendelian randomization study, were consistent and suggested an increased risk of oral cancer in IBD patients. In the study by Katsanos et al., it was demonstrated that patients with IBD had an elevated risk of malignant tumors in the oral cavity, particularly tongue cancer.20 Immunosuppression, dysbiosis, a weakened immune system, and HPV infection are key risk factors. In light of these findings, the importance of regular dental examinations, patient education and preventive HPV vaccination in patients with IBD should be emphasized. Omitting HPV vaccination in patients with IBD is acknowledged as a significant vaccination oversight.27 Studies showing no association between HPV vaccination and the IBD risk are also relevant.28

Thyroid cancer

Thyroid cancer includes papillary TC, follicular cancer, medullary cancer, and poorly or undifferentiated cancer. Thyroid cancer stands as the most prevalent form of endocrine cancer, with papillary cancer comprising over 80% of all cases.29 It predominantly affects women and is more prevalent in white individuals than in African Americans.30 In our review, we identified 5 studies that evaluated the risk of TC in patients with IBD (Table 2).22, 31, 32, 33, 34 The results of the abovementioned studies are inconclusive. So et al. demonstrated that the risk of TC was not significantly higher in IBD patients as compared to the healthy population.22 In 2 studies, the risk of TC was higher only in patients with CD.31, 32 On the other hand, other studies indicate an elevated risk of this cancer only in patients with UC.33, 34

Lung cancer

Lung cancer (LC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with an estimated 1.8 million deaths worldwide.35 The available studies are inconclusive in assessing the relationship between IBD and LC (Table 3).33, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 Jung et al. showed that the risk of LC in IBD patients was similar to that in the general population.33 In turn, other studies suggest a link between CD and an increased risk of LC, which is not confirmed in UC, even indicating a reduced risk of lung cancer in this group of patients.36 Yet, the meta-analysis published in 2021 by Lo et al. suggests an increased risk of LC in IBD patients.40

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer in women, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases diagnosed globally each year.41 The known risk factors for BC are increasing age, prolonged estrogen exposure, obesity in postmenopausal women, reproductive and genetic factors, western lifestyle, as well as smoking and alcohol consumption.41 It seems that IBD patients have a shorter period of estrogen exposure as compared to the general population. This is due to a later onset of menarche and earlier menopause, which could be linked to a reduced risk of BC.42 In our review, only Van den Heuvel et al. noted a decreased risk of BC in female patients with IBD.43 Three out of the 5 studies showed an increased risk of BC in IBD patients, while the rest reported a risk similar to that in the general population (Table 4).37, 39, 43, 44, 45

Pancreatic cancer

The findings are consistent and indicate a higher risk of PC in patients with IBD (Table 5).33, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 A recently published meta-analysis of 11 cohort studies unequivocally showed a moderate increase in the PC risk in patients with IBD.51 Moreover, the study demonstrated a significantly higher PC risk in men with IBD as compared to women.51 The incidence of PC has been increasing worldwide yearly. The link between PC and IBD is primarily attributed to the chronic systemic inflammation caused by the disease. Kimchy et al. suggests that this increasing trend observed in the IBD population parallels the increase in the incidence of PC reported among the general population, but at a much greater rate.49 In their study, Jung et al. observed an increased risk of PC, specifically in women with CD.33 On the other hand, Burish et al. noted an increased risk of this cancer in patients with UC.48 A particular factor that increases the risk of PC in patients with IBD is the presence of PSC. In a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies, the summary relative risk (RR) (95% confidence interval (CI)) comparing persons with PSC to persons without PSC was 7.56 (2.42–23.62; I2 = 0%, n = 3) for PC.52

Hepatobiliary cancer

The available studies suggest that in patients with IBD there is a higher risk of hepatobiliary tumors (Table 6).33, 37, 53 The risk is especially high in patients with PSC. Concomitant IBD is reported in up to 60–80% of PSC patients.54 There are strong positive associations between PSC and several tumors. For instance, in a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies, the summary RR (95% CI) comparing persons with PSC to persons without PSC was 584.37 (269.42–1,267.51; I2 = 89%; n = 4) for cholangiocarcinoma, 155.54 (125.34–193.02; I2 = 0%; n = 3) for hepatobiliary cancer and 30.22 (11.99–76.17; I2 = 0%; n = 2) for liver cancer.52

Urinary tract cancer

Urinary tract cancers comprise urinary bladder cancer (UBC), which tends to develop in older males, particularly those who smoke or have chronic inflammation, and renal cell carcinoma (RCC), which is associated with smoking, obesity and hypertension.55, 56 In the early stages of RCC, elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a crucial mediator of cancer-related inflammation, have been observed.57 Also in the case of urinary tract cancers, the results of the studies included in our review are ambiguous (Table 7).22, 32, 33, 46, 53, 58, 59, 60 Importantly, an association between urinary tract cancer and thiopurines was suggested. In a French study, the incidence rates of urinary tract cancer were 0.48/1,000 patient-years in patients receiving thiopurines (95% CI: 0.21–0.95), 0.10/1,000 patient-years in patients who discontinued thiopurines (95% CI: 0.00–0.56) and 0.30/1,000 patient-years in patients never treated with thiopurines (95% CI: 0.12–0.62) at entry.60 In turn, in another study, IBD patients had a significantly lower age at the RCC diagnosis, lower N-stage and lower M-stage, underwent more frequent surgical treatment for RCC as compared to the general population, and had a better survival independent of immunosuppression.59

Prostate cancer

In men, prostate cancer (PCa) ranks as the most frequently diagnosed cancer in 118 countries.61 Men with IBD demonstrated a shorter time to develop PCa. An increasing adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) across years since the IBD diagnosis was observed (≤20 years, aHR: 1.22; >20 years, aHR: 1.49; p-trend = 0.018).62 Men with IBD had higher rates of clinically significant PCa when compared with age- and race-matched controls.63 In the majority of the analyzed studies, an increased risk of PCa was observed in patients with UC (Table 8).22, 33, 36, 43, 46, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67

Reproductive system cancers

The available studies regarding the association between IBD and reproductive cancers are inconclusive (Table 9).32, 33, 68, 69, 70, 71 Rungoe et al. investigated the association between the occurrence of precancerous cervical lesions, finding that both CD and UC patients had an increased risk of low-grade and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) as compared to the control group.68 However, the risk of cervical cancer (CC) was elevated only in patients with CD.68 Goetgebuer et al. also observed an increased risk of precancerous cervical lesions of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2+ grade in patients with IBD.70 The 2023 study by Hamid et al. reported a higher annual incidence of cervical, ovarian, endometrial, and vulvar cancers in female patients with IBD as compared to the general population.71 On the other hand, Kim et al. did not confirm an association between CC and IBD.69

Central nervous system malignancies

The number of studies assessing the risk of central nervous system tumors in patients with IBD is limited (Table 10).25 In 2023, a large, multicenter, prospective study was published, which included 12,882 patients with IBD; it was found that there was a relationship between IBD, CD and brain malignancies.25 More population studies are required to validate this correlation.

Hematological malignancies

The relationship between hematological malignancies and IBD is of great interest. Two large meta-analyses focusing on this relationship have been published recently.51, 67 They have shed new light on the not always consistent results of single studies.32, 53 Although further research work is needed, the abovementioned studies organize current knowledge, and provide a practical signpost for gastroenterologists and oncologists.

Zhou et al. demonstrated that the incidence of hematologic malignancies in the IBD cohort, both CD and UC patients, was higher than in non-IBD individuals.67 Furthermore, the incidence of specific malignancies – non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia – was also higher in IBD patients.67

Zamani et al. published a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies that evaluated the risk of lymphoma in patients with IBD in comparison with those without IBD.51 The research demonstrated that the risk was moderately increased in patients with IBD, with CD having a slightly higher risk than UC. Considering the strengths of the study, especially the type of studies included and a very high number of participants, the significance of the findings showing a 30% higher risk of lymphoma in patients with IBD should be highlighted. Furthermore, based on the meta-regression and sensitivity analysis, Zamani et al. concluded that the overall increased risk of lymphoma in IBD was probably independent of the effects of medications. This is another important finding of the study considering the association between drugs, especially biologics and immunomodulators, and the risk of lymphoma.51 All the mentioned studies are presented in Table 11.32, 51, 53, 67

Skin cancers

There are well-recognized associations between IBD and skin cancers, which are most frequently linked to specific therapies (Table 12).22, 39, 43, 46, 72 The risk of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and melanoma was increased in thiopurine and anti-TNF users, and the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was increased only in thiopurine users.72

Effect of the use of thiopurines on the risk of developing extraintestinal malignancies

Despite the development of molecularly oriented therapeutic strategies, thiopurines, such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine, still play an important role in treating IBD. Yet, the treatment with thiopurines in IBD patients is associated with an increased risk of developing hematological malignancies, non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), urinary tract cancers, and CC. However, the latter association is uncertain.

Hematological malignancies

Several studies have found that the use of immunosuppressive treatment with thiopurines may increase the risk of hematological malignancies in patients with IBD. A prospective observational study involving 19,486 IBD patients included in the Cancer et Sur-risque Associé aux Maladies Inflammatoires Intestinales en France (CESAME) showed that IBD patients who were currently treated with thiopurines and those who had never received the drugs showed no increased overall risk of lymphoproliferative neoplasms, including acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome.73 In contrast, patients who had been exposed to thiopurines in the past had a 7-fold increased risk of developing lymphoproliferative neoplasms.73 Kotlyar et al. in a meta-analysis proved that the incidence of lymphoma during thiopurine use was almost 6 times higher, but this risk did not persist after thiopurines were discontinued.74 Selected studies on the association between thiopurine therapy in IBD and hematological malignancies are presented in Table 13.67, 74, 75, 76

Urinary tract cancers

Studies on thiopurines and the urinary tract cancer risk present conflicting results. A cohort study involving 1,986 IBD patients, 30.1% of whom were receiving thiopurines, found that patients treated with thiopurines were at increased risk of developing urinary tract cancer.60 In contrast, in a retrospective study, Caviglia et al. found no clinically significant association between thiopurines use and urothelial carcinoma.77 The analyzed studies are presented in Table 14.60, 75, 77

Cervical cancer

The effect of immunosuppressive drugs on the development of dysplasia and CC in IBD has been addressed many times and is still controversial.

A meta-analysis published in 2015 found an increased overall risk of cervical dysplasia and CC in IBD patients with current or prior treatment with immunosuppressive drugs as compared to the general population.78 However, this study has a limitation, as it did not take into account the effect of specific immunosuppressive drugs, the actual or cumulative dose, or the duration of therapy.78 Of a different opinion are Mann et al., who in their meta-analysis did not confirm an increased risk of CC for patients using thiopurines.79 In turn, Goetgebuer et al. found an increase in the risk of CIN2+ due to exposure to immunosuppressants.70 A detailed overview of the studies under analysis is provided in Table 15.70, 78, 79

Biological treatment and extraintestinal malignancies

The invention of biological drugs, and consequently their incorporation into the treatment standards for individuals with IBD, has significantly changed the approach to patient management. In addition to the obvious benefits of better control of the underlying disease, several challenges have also emerged that need to be addressed. Biological drugs have various mechanisms of action, but their common feature is the suppression of the immune system. The biologics used in IBD include: TNF-α inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab); anti-integrin drugs (vedolizumab – a humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that blocks the binding of integrin α4β7 to MAdCAM-1, preventing lymphocyte migration to the intestines); drugs targeting the interleukin (IL) IL-12/IL-23 pathway (ustekinumab – a human monoclonal antibody targeting the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, inhibiting the binding of Il-12 and Il-23 to their respective receptors on the surface of T and NK cells, others – mirikizumab, rizankizumab).80, 81

TNF-α inhibitors and the risk of extraintestinal malignancies

Several studies have addressed the issue of the impact of using anti-TNF inhibitors in the treatment of IBD on the development of extraintestinal cancers (Table 16).76, 82, 83, 84 Lemaitre et al., based on data from a cohort study involving 189,289 patients with IBD, concluded that there was a small, but statistically significant increase in the risk of lymphoma associated with the use of TNF-alpha inhibitors.76 The risk of cancer was even higher when TNF-alpha inhibitors and thiopurines were used concurrently.76 Chaparro et al., in their observational cohort study involving 11,011 patients from the Spanish ENEIDA registry, did not observe an association between the use of immunosuppressants (mainly thiopurines) nor anti-TNF drugs and an increased risk of EMs in individuals with IBD.83 The study considered lymphomas, leukemia, NMSC, and melanoma skin cancer (MSC).83 Similarly, D’Haens et al.82 and Kopylov et al.84 did not describe an association between the use of anti-TNF inhibitors and an increased risk of EMs.

Anti-integrin drugs (vedolizumab) and the risk of extraintestinal malignancies

Colombel et al. in their meta-analysis found no significant association between the use of vedolizumab and an increased risk of EMs.85 Furthermore, all patients exposed to vedolizumab who were diagnosed with skin cancer had a history of azathioprine therapy, and 2 continued to use azathioprine in the study.85 Card et al., based on data from the GEMINI long-term safety (LTS) study, found that the number of malignancies occurring in patients using vedolizumab was similar to the expected number of malignancies in a population of IBD patients not using vedolizumab.86 Singh et al. demonstrated that the use of vedolizumab did not increase the risk of malignancy as compared to infliximab.87 In a meta-analysis conducted by Cohen et al. on a very large number of patients, we can find information that among EMs in patients with CD, there was UBC and KC, and then skin cancer, and among patients with UC – lymphomas and respiratory malignancies.88 The study did not note any new safety concerns. The incidence of adverse events, such as malignancies, was low enough considering the patient-years of exposure to confirm the favorable safety profile of vedolizumab.88 Additionally, a recent multicenter cohort study demonstrated no difference in cancer incidence in the IBD patients with prior non-digestive malignancy, treated with vedolizumab or anti-TNF.89 The studies included in the analysis are listed in Table 17.85, 86, 87, 88

Drugs targeting the IL-12/IL-23 pathway (ustekinumab) and the risk of extraintestinal malignancies

In their study, Hong et al. showed that there was no association between the use of ustekinumab and the occurrence of malignancy in patients with prior malignancy.90 Sandborn et al. showed in their meta-analysis that taking ustekinumab did not increase the risk of malignancy as compared to placebo.91 Table 18 provides a summary of the study results.90, 91

Small-molecule drugs and extraintestinal malignancies

There are 2 basic groups of small-molecule drugs: Janus-activated kinase (JAK) inhibitors (including tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib); and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulators (including ozanimod), increasingly used to treat IBD.92 Chen et al. in their meta-analysis did not show any association between the use of small-molecule drugs and the occurrence of malignancy.93 Goessens et al., in their observational study of IBD patients receiving combination therapy consisting of biologics and small-molecule drugs, observed that in patients with a previous history of malignancy there was no recurrence of cancer.94 The results of the discussed studies are presented in Table 19.93, 94

Molecular and immunological mechanisms of extraintestinal malignancies in inflammatory bowel diseases

One of the leading factors contributing to an increased risk of cancer in IBD is the chronic inflammatory process.95 The available studies indicate that this factor plays a key role not only in the development of CRC or small bowel adenocarcinoma, but also EMs. Other factors, such as an older age, smoking, HPV infection, and the coexisting PSC, may independently increase the risk of developing EMs in IBD.96 Chronic inflammation in IBD leads to the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, like TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-17, which drive cancer development by activating key signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, JAK/STAT, Wnt/β-catenin, and PI3K/AKT. Inflammation leads to oxidative stress by overproducing reactive oxygen species, which can damage DNA and contribute to cancer-related genetic changes.97 Gut microbiota is the key to maintaining intestinal balance and immune regulation. Dysbiosis is strongly associated with IBD, colitis-associated cancer, and could also contribute to the formation of EMs. Harmful bacteria, like F. nucleatum and certain E. coli strains, can disrupt the mucosal barrier, trigger inflammation and promote carcinogenesis through mechanisms such as toxin production and DNA damage.98

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. Our literature search was limited to the papers published after January 1, 2015, to review the most recent studies. Due to the changing incidence of cancer and dynamic changes in IBD therapy, we decided to limit our search to the last 10 years. Studies of EMs in IBD were characterized by high heterogeneity. Several studies were of retrospective nature and referred to a small sample of IBD patients. The results of these studies do not provide strong evidence and must be interpreted with extreme caution.

Conclusions

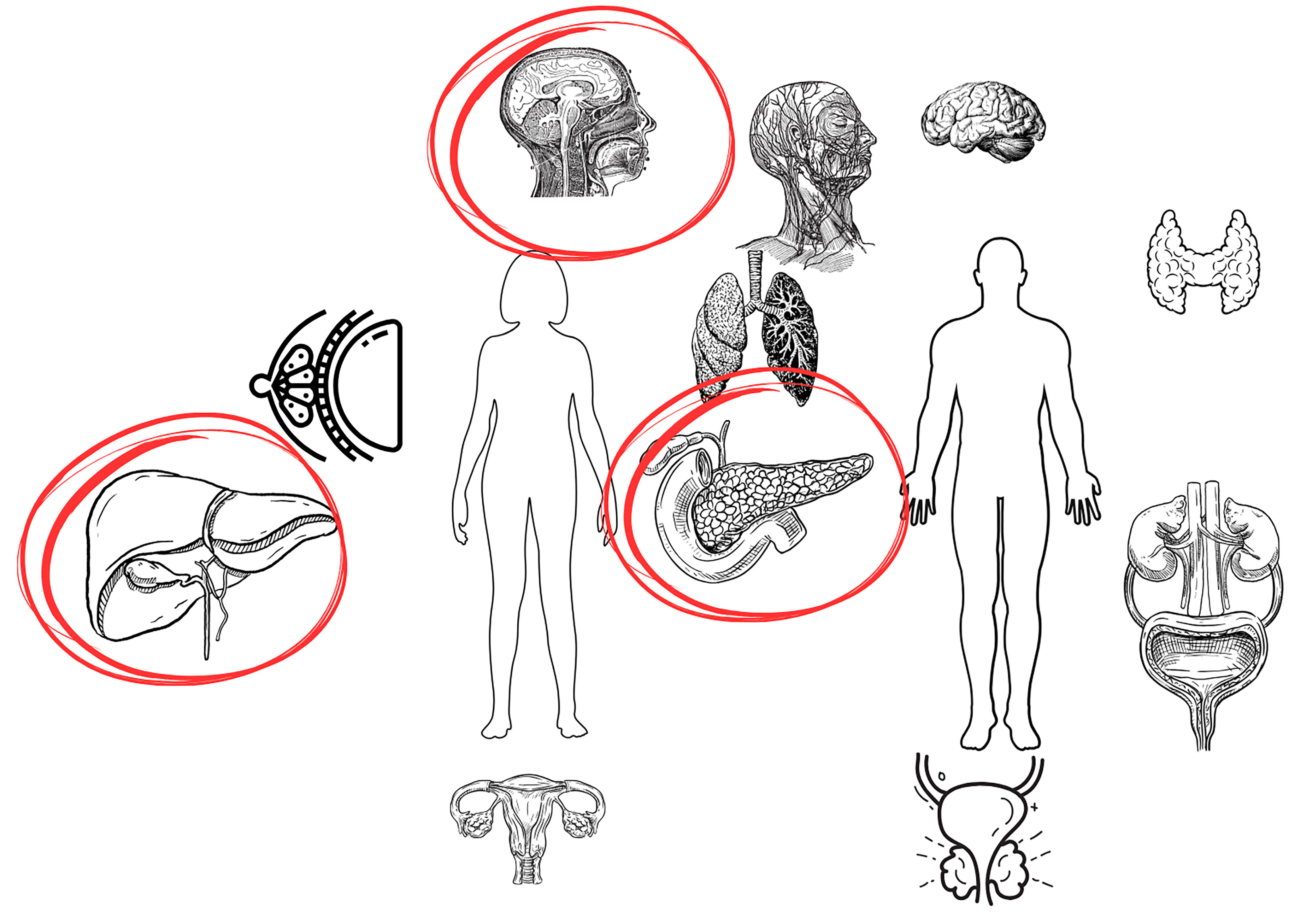

An increased risk of oral, pancreatic and hepatobiliary malignancies is observed among EMs in IBD patients (Figure 2). As for other types of EMs, the results of the presented research are inconsistent and require verification in large population studies.

The dynamic epidemiological situation, combined with the methodological limitations of many existing studies, underscores the need for further research to better understand the relationship between IBD and cancer. In this group of patients, special oncological vigilance, the employment of the available prevention methods (e.g., vaccination), patient education, and, when recommended, screening tests are required. A clinical challenge involving a multidisciplinary approach is the treatment of IBD in cancer patients, especially during disease exacerbation, as well as cancer therapy in IBD patients.

It should be emphasized that the overall risk of EMs in IBD patients remains low, and even if the therapies used are associated with an increase in this risk, it should not influence the decision on the optimal available therapy.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

The graphical abstract and the figures were created using Canva.