Abstract

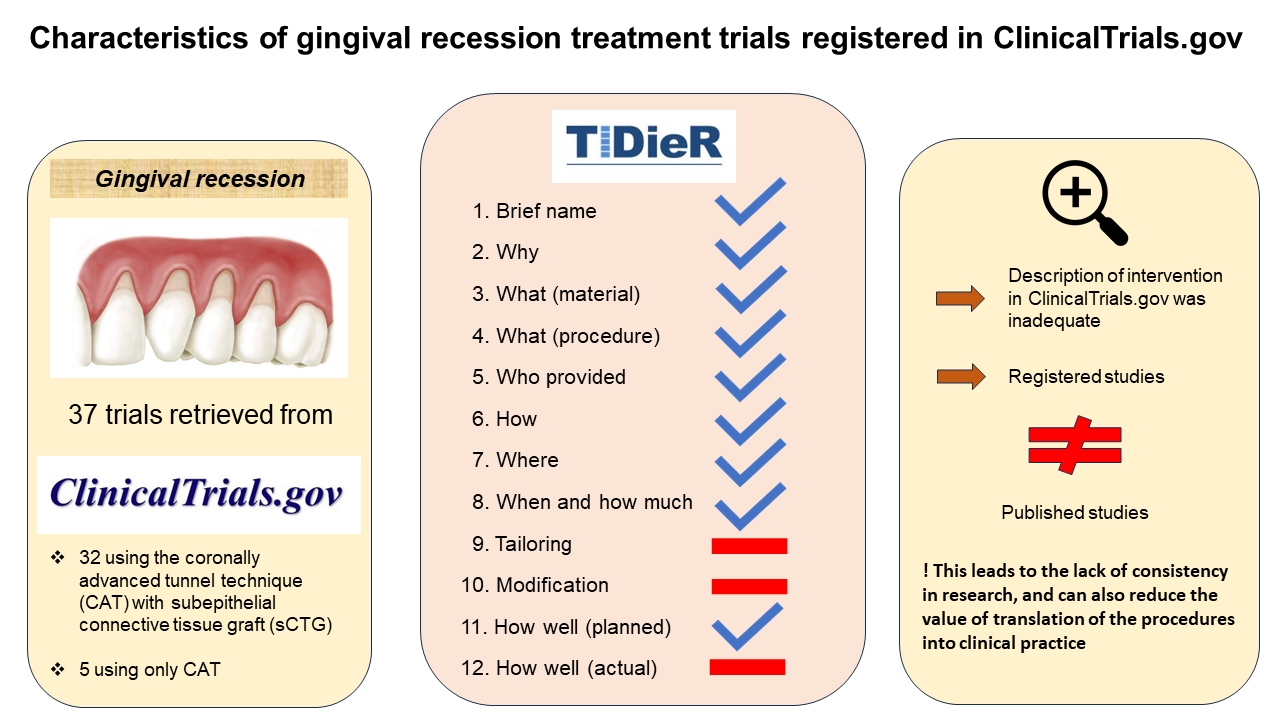

Gingival recessions are a common disease and one of the most frequently used method for managing them is the tunnel technique (TUN). Although more and more articles are addressing the problem, few are adequately structured, usually without following the standard protocols. Many checklists have been developed for this purpose. Among them, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist is commonly used. Therefore, the present review analyzed trials based on it. The completeness of registration of the trial protocol data was assessed using the TIDieR checklist with regard to the coronally advanced tunnel technique (CAT) with subepithelial connective tissue graft (sCTG) (CAT + sCTG) and CAT alone. The review also investigated the consistency of the research description in the published articles.

A total of 37 records were gained from ClinicalTrials.gov and the corresponding publications, including 32 studies employing CAT + sCTG and 5 studies using only CAT.

The description of intervention in ClinicalTrials.gov was inadequate for all analyzed trials, and there were also differences between the registered and published studies.

The present analysis showed that the description of the registered trials is often incomplete and that detailed data is not pro-vided. It is essential that clinical research is well documented and properly described, so that the findings can be easily implemented in daily clinical practice without confusion.

Keywords: checklist, reporting, database, gingival recessions

Introduction

Gingival recession is described as an apical displacement of the gingival margin, which can be associated with root caries, dentin hypersensitivity and esthetic outcomes.1 It is a very common condition that can affect people regardless of the level of oral hygiene, and its incidence increases with age.2 This disorder can be a tough issue to treat and manage.3

Over the years, several surgical techniques have been developed to treat gingival recessions.4, 5 Evidence shows that the coronally advanced flap (CAF) method and the tunnel technique (TUN) lead to satisfying results.6 Many modifications to those procedures have been introduced to improve the final outcome.7

The tunnel technique is known as a minimally invasive procedure to treat gingival recessions. This method eliminates vertical releasing incisions, leaving the interdental papillae intact.8 Therefore, this treatment leads to a greater blood supply and faster healing, and reduces post-operative morbidity.9 Over the years, TUN has gained popularity due to its high effectiveness in treating multiple gingival recessions.10

The short- and long-term outcomes in terms of gain of keratinized tissue depend on using subepithelial connective tissue graft (sCTG).11, 12 Although potential alternatives to harvesting a graft from the palate have been proposed, such as enamel matrix derivatives,13 collagen porcine dermal matrix,14 concentrated growth factors,15 or titanium-prepared platelet-rich fibrin (T-PRF),16 sCTG is still considered the gold standard.17 On the other hand, research confirms that in many cases, using the coronally advanced tunnel technique (CAT) alone results in the complete coverage of the recession and is stable over time.

In order to properly apply a specific method in practice, scientific research should be adequately described in detail. Various checklists have been developed for this purpose, for example the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 statement,18 the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement19 and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR).20

The TIDieR checklist regarding the description of intervention21, 22, 23 should be implemented not only in the published articles, but also in trial registries, since usually, all the information about the conducted trials is included there.

The present review is the first to analyze published articles on gingival recession treatment in terms of consistency and transparency. Moreover, it advises researchers to adhere to established guidelines when preparing scholarly articles. It is important for young scientists to write according to certain standards to maintain consistency and clarity in their articles.

So far, there has been no research on the use of specific standards while writing articles on the coverage of gingival recessions. This is an important issue, taking into account the prevalence of gingival recessions and the increasing number of studies conducted on this topic.

The aim of the present study was to assess the completeness of the description of gingival recession treatment procedures in the clinical trial protocols registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, as well as the consistency of the research description in the published articles. It can be a useful guide for inexperienced researchers to include necessary details in the conducted studies.

Material and methods

Sample and inclusion criteria

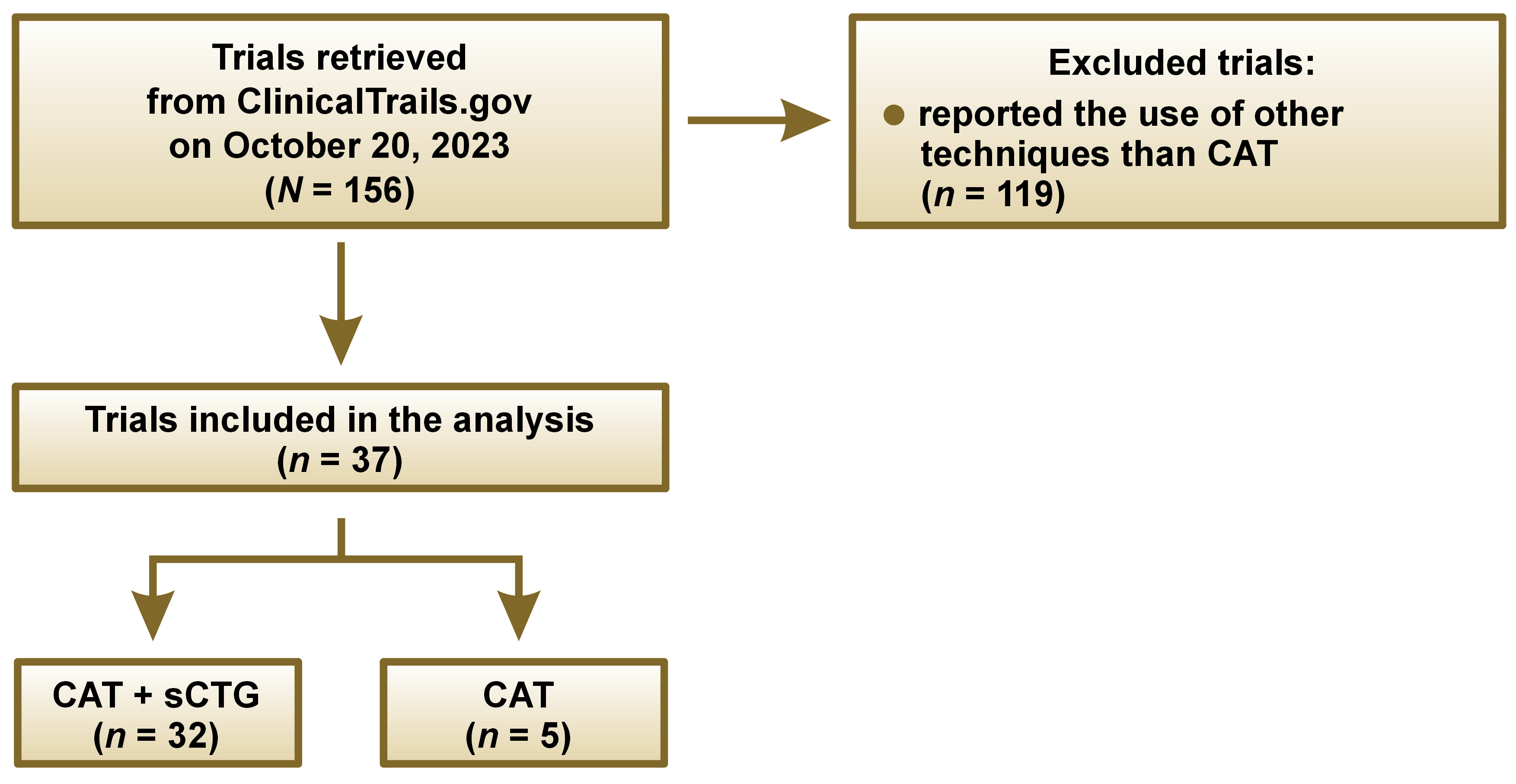

The search for clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov was conducted on October 20, 2023. It was decided to analyze the research posted in ClinicalTrials.gov, as this online database provides information about the results of clinical research studies. The term “gingival recession treatment” was used in advanced search. Then, all trials regarding gingival recession treatment were reviewed, and studies using the CAT method, with or without sCTG, were selected for analysis. Then, another screening of studies was conducted based on the inclusion criteria: articles that referred to gingival recession treatment in one or more fields in ClinicalTrials.gov (Brief Title, Official Title, Brief Summary, or Intervention); those with a National Clinical Trial (NCT) number; described as completed, recruiting, withdrawn, active non-recruiting, or terminated; and registered in October 2023 or earlier. Trials that used other techniques to treat gingival recession than CAT were excluded.

Data extraction

In order to fully register trials, the World Health Organization (WHO) prepared a checklist – WHO Trial Registration Data Set – with 24 items. Of these, the following 21 items were taken into account in our research: the trial identifying number (ID); the NCT number, the source(s) of monetary or material support; primary and secondary trial sponsors; the public title; the scientific title, the countries where the trial was conducted; the health condition(s) studied; the intervention(s); the inclusion criteria; the study type; the date of first enrollment; the sample size; the recruitment status; the primary outcome; the key secondary outcomes; the date of study completion; summary results; and the individual participant data (IPD) sharing statement. Contact for public queries, contact for scientific queries and the ethics review were excluded.

To assess the completeness of the description for each intervention in gingival recession treatment, we used the 12-item TIDieR checklist.20 The trials included in the analysis referred to either CAT alone or CAT + sCTG. The interventions employing other techniques than CAT were excluded from the analysis and need further investigation. The trials from ClinicalTrials.gov were verified, and key data from a random 10% sample were independently extracted by an experienced periodontologist and a general dentist (PhD student). Some unclear studies were identified and reviewed in collaboration with another reviewer, a final-year dental student working under supervision. At the end of the analysis, all authors reviewed the included studies and resolved any disagreement through discussion.

All the information was obtained from the Descriptive Information section in ClinicalTrials.gov. None of the papers provided data related to points 9, 10 and 12 of the checklist, so we referred to 9 items only in the analysis. The interventions were checked for data consistency in the PubMed® and Google Scholar databases. The information from ClinicalTrials.gov was compared with the corresponding publications. After checking 157 interventions, we excluded 119 of them, since they used other type of technique to treat gingival recessions. Most data regarded CAF coronally advanced flap,6 as it leads to excellent results. Fifteen studies did not mention the method used, and 3 papers did not provide the name of the method, but the description indicated the use of CAF.

Results

The study included 37 trials retrieved from ClinicalTrials.gov. on October 20, 2023, as shown in Figure 1. As many as 32 (86%) reported using CAT + sCTG, and 5 (14%) used CAT alone.

The registration numbers of the trials qualified for analysis, using CAT with sCTG: NCT05688293; NCT04291963; NCT02632240; NCT05270161; NCT03791554; NCT02642887; NCT03657706; NCT05122468; NCT04133298; NCT06000228; NCT03163654; NCT04028037; NCT04104087; NCT05819515; NCT05568732; NCT04561947; NCT05045586; NCT03354104; NCT03162016; NCT06044870; NCT04966208; NCT05823415; NCT03676088; NCT06030947; NCT02916186; NCT02814279; NCT04016493; NCT04198376; NCT05976451; NCT02774967; NCT03690635; and NCT05436002.

The registration numbers of the trials qualified for analysis, using CAT without sCTG: NCT04513041; NCT04225351; NCT0565247; NCT03619096; and NCT04802473

At first, the general research characteristics were analyzed for both group of trials (Table 1). We collected data about the status – unknown, recruiting, active not recruiting, or completed. Most of the papers (n = 34; 92%) did not provide any data on the study phase, 3 trials (8%) declared phase 2 (n = 1; 3%) or 4 (n = 2; 5%).

Almost all trials (n = 36; 97%) were described as interventional, and only one paper (3%) as observational. The majority of articles (n = 34; 92%) applied randomized allocation, 1 trial used non-randomized allocation, and 2 studies (5%) stated “not applicable”. The most frequently used interventional model was parallel assignment (n = 33; 89%). Trials also applied a single-group model (n = 3; 8%), crossover assignment (n = 1; 3%) and 1 paper (3%) used the term “other”, but did not mention the type.

The included trials applied different types of masking: none (open-label) (n = 5; 14%); single-blind (n = 12; 32%); double-blind (n = 10; 27%); triple-blind (n = 9; 24%); and quadruple-blind (NCT02916186; n = 1; 3%). The majority of trials mentioned treatment as the primary purpose (n = 36; 97%); only 1 study did not provide the aim of the study (Table 1).

The next step was the comparison of the participant characteristics (Table 2). All studies included volunteers of both genders, provided their age and enrollment. Most of the trials accepted healthy participants (n = 25; 68%). Fifteen papers (41%) did not apply the IPD sharing, 10 studies (27%) stated “undecided” and 12 trials (32%) claimed “not provided”.

Quality of description of the main interventions in ClinicalTrials.gov

All the 32 trials using CAT + sCTG briefly described the intervention, and provided information about materials, procedures and the location where the intervention was applied (Table 3).

The majority of these studies (n = 30; 94%) mentioned the goal of treatment, which was determining the effect of root coverage. A total of 19 included trials (59%) reported a periodontist as a person responsible for treatment, 3 studies (8%) provided unclear information and 10 papers (31%) did not mention the investigator.

Only 6 studies (19%) provided information with regard to TIDieR item 6, specifying that the participants received verbal or written instructions. All the trials provided the time frame of the study, and 24 papers (75%) also mentioned the number of sessions.

In our article we included 5 studies using CAT to treat gingival recessions (Table 4). All papers provided a short description, and information about materials and procedures. Most of the studies (n = 4; 80%) mentioned the aim of the study. The expertise provider as well as the investigation center were mentioned in 100% trials. Similar to the intervention reporting in the trials using CAT with sCTG, 20% papers described indications for volunteers.

For only one trial out of 32 (3%; NCT03676088), we identified accordance with the CONSORT criteria.

Comparison of the registry data and the corresponding publications

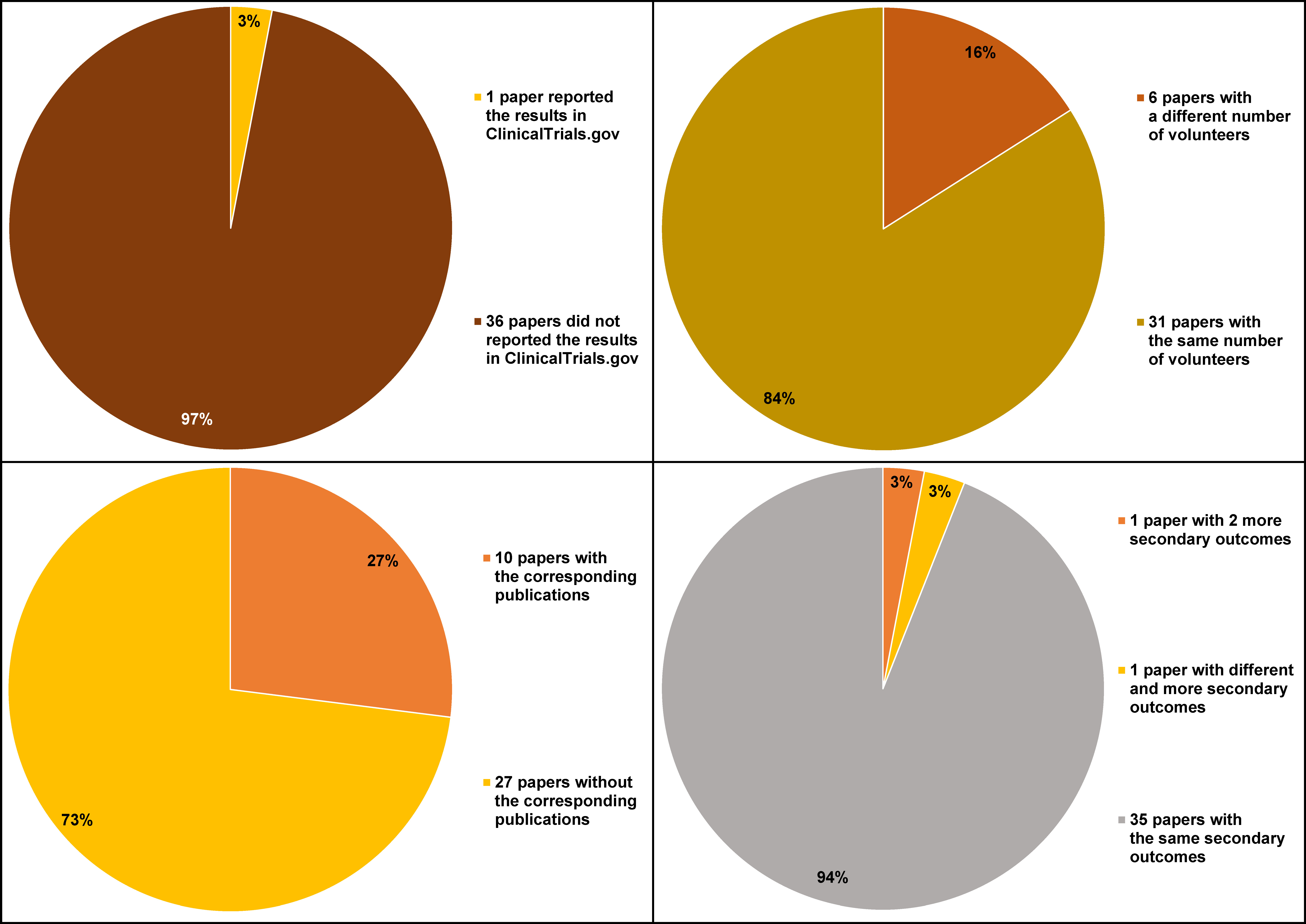

For the 37 registered papers analyzed in the study, we were able to identify 10 corresponding publications, searching PubMed and Google Scholar. The number of participants, and the primary and secondary outcomes were compared (Figure 2). In 6 cases, the number of volunteers in the published article was different from that in the registry.

The primary outcomes were the same in ClinicalTrials.gov. and in the published articles. In the case of 1 trial (3%) (NCT02916186), there were 2 more secondary outcomes provided in the released paper, i.e., patient esthetic satisfaction and postoperative pain on a visual analog scale (VAS). Another published article (NCT03163654) contained different and more secondary outcomes in comparison with the registry data, which was the root coverage esthetic score, keratinized tissue width and gingival thickness gain, whereas in the corresponding trials, gingival recession width, keratinized tissue width, gingival thickness, and clinical attachment level (CAL) were provided.

Only one included study (NCT02814279) reported the results in ClinicalTrials.gov.

Discussion

The tunnel technique is recognized by periodontal specialists as one of the easiest and at the same time effective methods of covering gingival recessions, having many advantages in terms of dentin hypersensitivity reduction and esthetics, producing a significant gain in CAL and decreasing gingival recession.1 However, with regard to clinical trials, there is a need to establish the most predictable surgical approach for the treatment of this condition. The present study shows that the description of the registered trials is often incomplete and that detailed data is not provided. It is concluded, after comparing the registered papers with the published ones that there exist substantial differences between the provided information and instructions. Discrepancies concern mainly the number of participants and the reported outcomes.

A key limitation of our analysis is that over 60% of the trials posted in ClinicalTrials.gov were not linked to the corresponding publications, and only one study reported the results in ClinicalTrials.gov. Study data should be shared via ClinicalTrials.gov, as usually this is the only source of information on ongoing research. Moreover, the information should be transparent, detailed and easily available to the public; only then studies have a scientific value. For this reason, it is recommended to post the obtained results in ClinicalTrials.gov.24

Considering the high prevalence of gingival recessions, it is essential that clinical trials are well documented and properly described, so that the findings can be easily implemented in the treatment. Moreover, nowadays significantly more clinical trials are being carried out in periodontology over the years, wherefore all those studies should be adequately reported.25 In order to properly apply a specific method in practice, scientific research should be properly described in detail. Scientists should use the TIDieR guidelines to adequately report the studies.

Gingival recession treatment became predictable, with satisfactory results. Therefore, in our opinion, the ongoing research should be carried out according to specific guidelines, e.g., SPIRIT, CONSORT or TIDieR.18, 19, 20 To improve the quality of interventions and to allow adequate translation into clinical practice, clinical researchers and also journal editors should concentrate on precisely described papers.

The analysis focused on one of the most frequently used methods, i.e., TUN.6 To provide complete data on the ongoing trials regarding gingival recession treatment, we plan to analyze other methods, for example CAF.

Conclusions

Our review showed that the descriptions of intervention in gingival recession treatment trials were incomplete, and there were also differences between the registered and published studies. The main discrepancies concerned the number of participants, and the primary and secondary outcomes. This leads to the lack of consistency in research, and can also reduce the value of translation of the procedures into clinical practice.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.