Abstract

Background. A variety of natural and synthetic agents have recently been used in clinical trials to arrest dentin caries.

Objectives. The aim of the present study was to explore the remineralization and antibacterial effect of natural (propolis, hesperidin) vs. synthetic (silver diamine fluoride (SDF)) agents on deep carious dentin.

Material and methods. A total of 64 human molar teeth with Class I caries were randomly distributed into 4 groups: control group; propolis group; hesperidin group; and SDF group. The cavities were prepared using the stepwise caries removal technique, and then covered with the materials to be tested. The samples were taken from the carious lesions before and after treatment to evaluate the antibacterial effect. Then, the teeth were restored with a glass ionomer cement (GIC). Digital X-rays were taken to assess remineralization and the antibacterial effect after 6 and 12 weeks.

Results. The highest value of radiodensity was observed in the propolis group (46.44 ±9.65 HU), while the lowest value was noted in the hesperidin group (12.62 ±5.86 HU). The bacterial count in the propolis group was 1,280.00 ±1,480.54 CFU/mL at baseline, which was not significantly higher than the value measured after 6 weeks (574.00 ±642.48 CFU/mL; p = 0.153), whereas in the hesperidin group, the mean value of the bacterial count at baseline (3,166.67 ±1,940.79) was not much higher as compared to the value obtained at 6 weeks (2,983.33 ±1,705.77) (p = 0.150).

Conclusions. In comparison with SDF, propolis and hesperidin agents showed promising effects in terms of remineralization of carious dental tissue and hindering the progression of caries.

Keywords: propolis, remineralization, dental caries, hesperidin, silver diamine fluoride, antibacterial effect

Introduction

In an era aiming to conserve dental tooth tissue, strategies for the management of dental lesions, both carious and non-carious, have evolved to preserve tooth structure and minimize removal. In the oral cavity, teeth are often affected by various alterations, such as dental caries, abnormal teeth, enamel hypoplasia, supernumerary teeth, and dental agenesis. Dental caries is characterized by areas of regional tooth tissue deterioration caused by bacterial flora and acid products which cause demineralization of tooth structure and proliferation of bacterial colonies. On the other hand, non-carious lesions are characterized by a loss of hard dental tissue due to nonbacterial factors, especially near the cement-enamel-junction. These lesions frequently cause dentin hypersensitivity and can promote the development of additional caries. While the major difference between carious and non-carious lesions is the bacterial factor, a non-carious lesion may result in retentive niches in which bacteria can flourish and create a pathological biofilm, which in turn promotes further carious lesions.1 Risk factors for the development of caries include all conditions that can cause difficulties in oral hygiene and also orthodontic brackets. Other conditions that can cause oral hygiene problems include Psychiatric disorders, genetic disorders or genetics syndromes and other debilitating conditions connected with manual labor.2, 3 Temporomandibular disorders and other mouth pain conditions such as lesions of oral mucosa may limit mouth opening and hinder proper hygiene.

Once a lesion develops, conservative modalities should be employed to treat or heal the lesion.4, 5, 6 Among the conservative modalities used include the treatment of hypersensitivity using diode laser treatment. Conservative modalities for caries management also include recognition of risk factors, as well as early detection and remineralization of incipient carious lesions.7, 8 Carious lesions can progress over time and develop into the pulp and as they penetrate deeper into tooth structure, thus preservation of the remaining dentin becomes of paramount importance. In addition, the neutralization of the remaining bacterial virulence is essential to arrest the lesion and prevent further pathogenesis. When the caries is destructive, extraction of the affected tooth is essential. This can change occlusal forces and increase the difficulty of teeth brushing, thus it is fundamental to rehabilitate all teeth as soon as possible. Rehabilitation can includes the use of an implant or a removable prosthesis.9, 10

Bacterial presence in deep cavities is reduced following incomplete carious dentin removal and tooth sealing when compared to traditional complete carious dentin removal. Additionally, the dentin beneath the interim restoration develops features of an inactive caries lesion (dry, hard, and dark).11 This has led to the evolution of selective caries removal modalities.

One of the main techniques used for selective caries removal is stepwise excavation. This technique involves retaining a layer of carious soft dentin above the pulp. After that, a protective liner is placed, and the tooth is sealed for a specific duration (30–45 days). The goal of this technique is to stimulate the development of tertiary dentin prior to complete excavation, hence decreasing the likelihood of pulp exposure.12, 13 Concern for the remaining bacteria in deep carious lesions remains controversial. While some authors have emphasized the seal as the primary factor for success of this technique, others have recommended the use of antibacterial agents for management of the remaining viable bacteria. The use of natural agents, such as tannins, terpenoids, flavonoids, alkaloids, have become very popular for the prevention of caries. The antibacterial activities of these agents have been found to be useful against dental caries.14, 15 Propolis, a bee product, has drawn interest for its safety and biological activity due to its polyphenolic compounds. Propolis is a flavonoid derivative resinous obtained from honeybees and from sprouts, exudates of trees and other parts of plants. It has antimicrobial, antitumor, anesthetic, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and healing properties. Polyphenols are another promising natural agents due to their ability to interfere with several pathways involved in the pathogenesis of some inflammatory conditions such as TMJ-related inflammation.16 The antibacterial activity of some natural materials (aloe vera and propolis) after minimally invasive hand excavation of dental caries have also been investigated. An antibacterial effect was assessed by visual assessment of the total number of viable bacterial unit-forming colonies. In a clinical trial comparing the effect of aloe vera and propolis on bacteria in hand excavated lesions, a significant amount of bacteria were left behind after hand excavation, but cavities treated with aloe vera and propolis extracts had a significant reduction in bacterial counts when compared to the control group.17 Another comparison was conducted between the effects of propolis fluoride (PPF) and nano-silver fluoride (NSF) to silver diamine fluoride (SDF) varnish for inhibiting Streptococcus mutans and Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation. The results of this analysis confirmed that NSF and PPF fluoride-based varnishes had greater antibacterial effects than SDF fluoride-based varnish.18

Hesperidin is a flavonoid extracted from citrus fruits. Hesperidin has anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-oxidant, and collagen cross-linking effects which limit the development of caries and enhance the remineralization process.19 Hesperidin has been added to dental adhesive in three different ratios producing four experimental adhesive groups (control, 0.2%, 0.5%, and 1%). Results showed that 0.5 wt% HPN incorporated dental adhesives could achieve a promising antibacterial effect without adversely affecting the adhesive characteristics.20

A variety of synthetic agents have also been used in clinical trials to arrest dentin caries. Some antimicrobial agents contain silver (Ag) such as silver diamine fluoride (SDF), which has a bactericidal effect and is affordable, effective, safe, and easy to use for stopping the progression of carries.21 Clinical trials have found that a topically applied SDF solution inhibits demineralization. Additionally, SDF inhibits the growth of cariogenic bacteria in biofilms, effectively prevents the development of caries, and meets the standards of the WHO Millennium Goals and the US Institute.22

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the remineralizing and antibacterial effects of natural agents (propolis, hesperidin) versus synthetic agents (silver diamine fluoride) after the treatment of deep carious dentin at different time intervals. The study was conducted to accept or reject the null hypotheses that:

There is no difference between natural and synthetic agents in remineralization effect of carious dentin.

There is no difference between natural and synthetic agents as antibacterial agents.

Material and methods

All materials used in this research are included in Table 1.

All procedures were carried out by two individuals. The first individual is the primary investigator who was responsible for all clinical procedures and collection of samples, whereas the second individual was responsible for microbiological assessment and lab procedures.

Study design

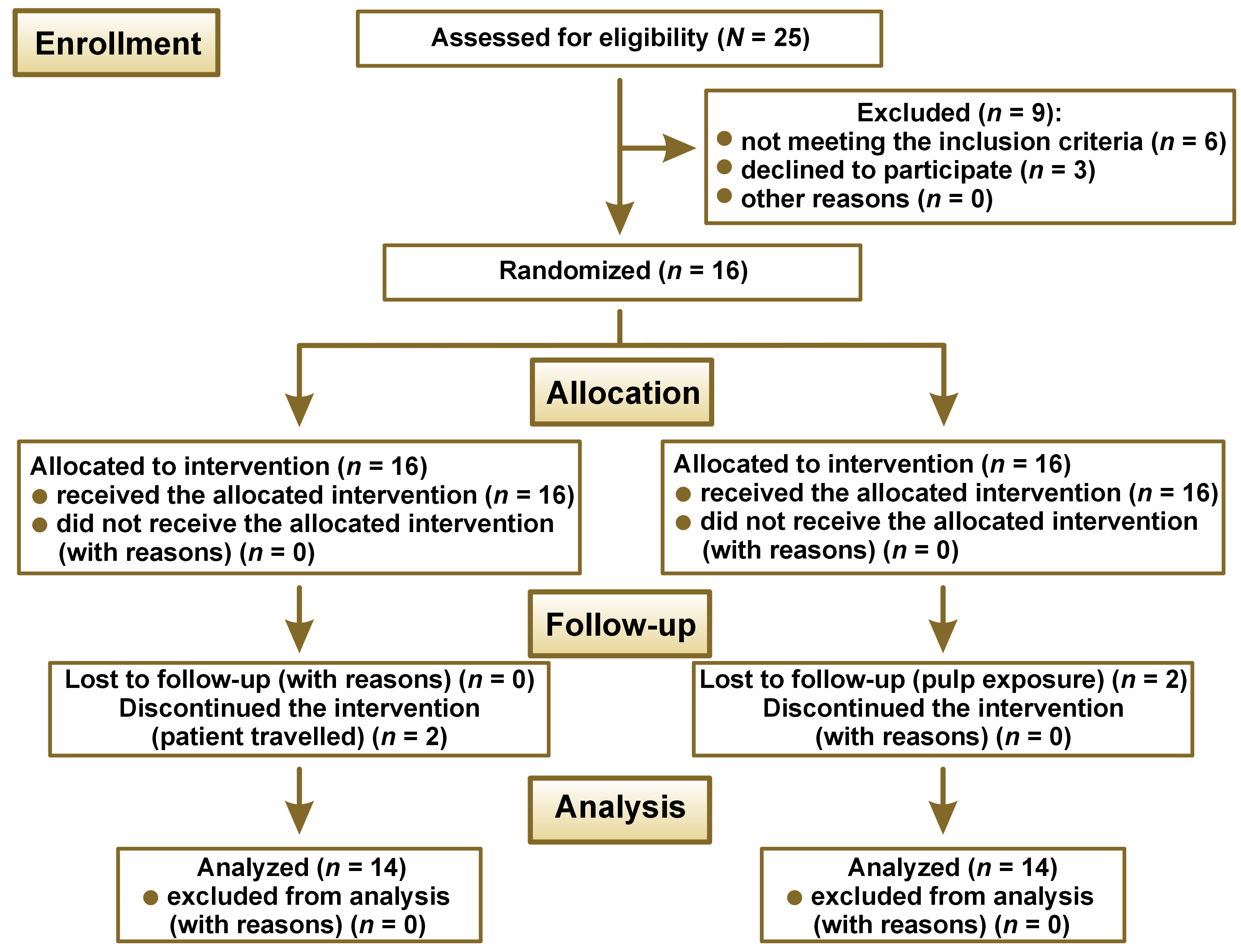

This clinical study was conducted in the restorative dental clinic at the Faculty of Dental Medicine for Girls of Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. It was conducted between January 2019 and March 2020. The study was planned in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 criteria (Figure 1). The Ethical Committee at the Faculty of Dental Medicine for Girls of Al-Azhar University approved the research protocol (REC-OP-21-05) and the trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under the identification number NCT04145102.

Patient recruitment and eligibility criteria

Participants were recruited from the outpatient clinics of the Faculty of Dental Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. Patients were enrolled in the study following the eligibility criteria presented in Table 2 after signing a fully descriptive informed consent.

Sample size calculation

According to Kabil et al 2018,23 assuming an alpha (α) level of 0.05 (5%) and a beta (β) level of 0.20 (20%), i.e., a power of 80% and an effect size (f) of 0.595, the estimated sample size (N) was a total of 48 samples, i.e., 6 per group. The overall sample size was increased by 25% to 64 to account for possible dropouts, i.e., 8 samples per group. The G*Power v. 3.1.9.2 software was used to determine the sample size.

Grouping of the samples

A total of 64 human teeth (upper and lower, first and second molars) were selected for this study. Teeth were grouped into four main groups of 16 each, according to the treatment agent applied (A): A1. propolis, A2. hesperidin, A3. SDF, and A4. control (no treatment). Each group was then divided into three subgroups according to the assessment time interval. Assessments were conducted at baseline which was obtained before treatment (B), after 6 weeks (B1), and after 12 weeks (B2) of applying the investigated materials.

Randomization, blinding,

allocation sequences

Randomization was undertaken using an excel sheet with random numbers. A list of sequential numbers was created, in which each randomly assigned participant in this list was assigned a sequence number (ID) from 1 to 16, to be assigned to one of the four treatment groups. This trial was double blinded.

Treatment procedure

Preparation of the cavities and baseline samples

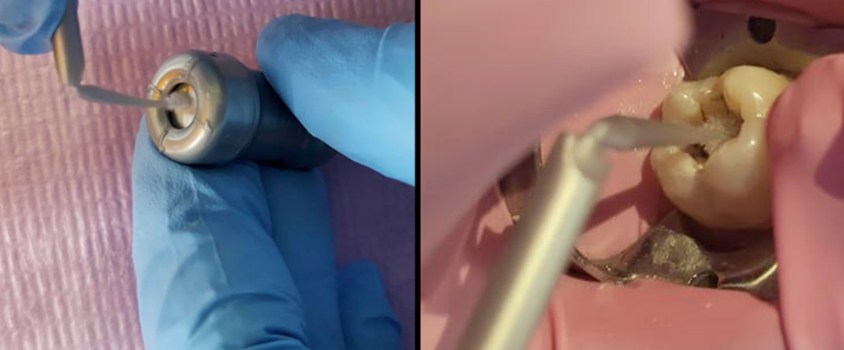

Pre-operative radiographs were taken using a digital X-ray machine (Kodak 2200; Kodak, Rochester, USA) with an imaging plate (digital sensor size 2; Dürr Dental, Bietigheim-Bissingen, Germany). Local anesthesia (Mepecaine- L) was administered with the infiltration technique and the nerve block technique for upper and lower arches respectively. Heavy sheet rubber dam isolation was applied, and class I cavities were prepared. Selective caries excavation technique was used to clean the pulpal floor using a spoon double ended excavator until leathery or firm dentin was reached as shown in Figure 2.

Samples of carious dentin were taken from the center of the carious lesion with the same-sized excavator for microbiological assessment. The samples were kept in sterile vials containing phosphate-buffered saline and delivered to the microbiology laboratory within two hours of extraction for processing.

Application of treatment agents

Each group received treatment following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Group A1 was treated by covering the remaining carious lesions after cavity preparation by propolis extract as shown in Figure 3. After preparation and toilet of the cavity the propolis extract was applied to the prepared floor by amalgam carrier, then condensed to cover the remaining carious lesion by condenser until a second sample could be taken depending on group allocation (i.e., group B1, 6 weeks; group B2 12 weeks).

Group A2 was treated with pure hesperidin powder mixed with distilled water at a 3:1 ratio to achieve a green like clay. The mix was applied using an amalgam carrier to the remaining carious lesion as shown in Figure 4.

Group A3 was treated by SDF+KI (RIVA STAR, SDI, Bayswater, Australia) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The capsules are color coded; the SDF is gray colored, and a brush was used to apply the material from the capsule and onto the cavity floor as shown in Figure 5. The second step involved using potassium iodide (KI) which is green coded and applied until a creamy white precipitate turned clear followed by oil free drying.

Restorative procedures

Stepwise excavation technique included two treatment visits. In the first visit, initial baseline digital radiograph was carried out prior to cavity preparation. A cavity was then prepared, and caries removed before cavity conditioning was done using a micro brush in a rubbing motion to all surfaces except the pulpal floor. Conditioner was rinsed using water for 10 s and moist dentin was maintained by eliminating excess water. This was followed by tested material’s application. Finally, a highly viscous glass ionomer cement glass ionomer (GIC) restoration material was applied to seal the cavities. Excess material was removed by a sharp explorer and allowed to sit for 6 minutes. Finishing by high-speed finishing stones was performed. Riva coat was applied and cured with LED intensity of 1200 mW/cm2 for 20 s. Another digital radiograph was taken and labeled baseline radiograph. Patients were dismissed with restoration retained until their second visit for recovery of the second dentin sample and second radiograph. Patients were instructed to maintain proper oral hygiene and to appear for all follow-up appointments.

For the second visit, the glass ionomer cement GIC was removed using a diamond bur with coolant and only the last layer of GIC was removed using a sharp spoon excavator. The last layer of GIC was identified with the guidance of the digital x-ray film taken on the first visit. Also, remaining carious dentin was mostly darker in color and created a dark shadow apparent beneath the last layer of the GIC. The hand instrument was used to preserve the most superficial layer of dentin for bacterial sample collection. A second sample was taken and handled as previously described. The cavity was then filled with highly viscous GIC base to the level of the dentin–enamel junction (DEJ), and then a final restoration was used. The timing of the second visit depended on which group the patient was allocated to. For B1 patients would come for a second image, sample collection, final restoration after 6 weeks, and then a final visit would occur at 12 weeks for a third image. On the other hand, B2 (12 weeks) patients would come after 6 weeks for imaging, and then again after 12 weeks for sample collection and third imaging Figure 6.

Final restoration was done with composite resin material using a selective etching technique utilizing 35% phosphoric acid on enamel surface for 15 s, rinsed with water for 15 s, gentle air water/oil-free for 5 s, blot-drying any moisture by absorbent tissue. A micro brush was used in a rubbing motion to apply a single layer of universal adhesive for 10 s, air drying for 5 s, and then light cured for 20 s. Shade selection was done, and 2 mm incremental packing of composite cured for 60 s was performed. Finishing and polishing was then conducted.

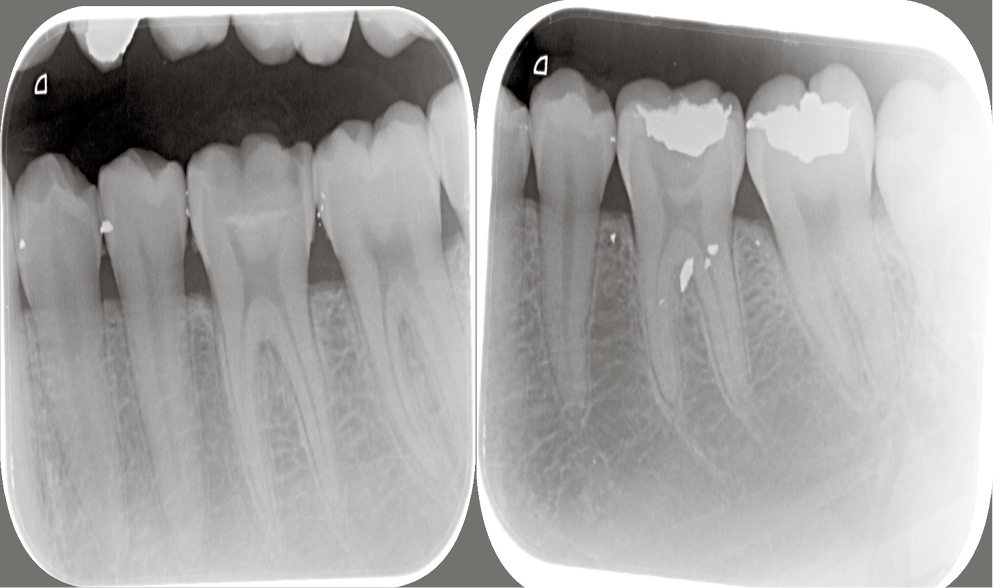

Assessment of remineralization

To assess the dentin remineralization, a digital X-ray machine (Kodak 2200) was used with DBSWin software at baseline, 6 weeks and 12 weeks, using a size 2 digital sensor and posterior parallel kit for image standardization that has 2 ends: one for X-ray cones and the other for the sensor. Then, the sensor was removed and scanning was performed with the use of Dürr Dental Vista Scan. The scans were stored for analysis.

Measurements in each sample were fixed for all samples at assessment intervals; 2 lines were drawn, one along the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) for reference and a second line parallel to it at the bottom of the cavity. The distance between the 2 lines was standardized for each tooth and measured by a vertical line connecting them. The DBSWin software was then used to determine the length in pixels and fix it for each sample. Three points on this line (at its start, middle, and end) were determined. The intensity of these points was recorded at each follow-up visit.

Bacterial assessment and processing

of the dentin samples

Samples were obtained from soft dentin carious lesions of permanent teeth of adult patients and transferred into a sterile 2 mL CryoTube™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) containing 1 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS), which then transported to the microbiology laboratory for analysis. Bacterial dispersion into the media from carious dentin samples was achieved by vortexing the samples for 30 s.

Isolation and identification of Streptococcus mutans

Using double ended sterile calibrated loops, 10 µL of the diluted samples were uniformly spread on the surface of mitis salivarius bacitracin (MSB) agar plates. The plates were sealed and incubated anaerobically by using a gas pack supplied in an anaerobic jar. Colonies of Streptococcus mutans were identified based on their unique morphology on MSB, with elevated, convex, opaque colonies of deep blue color with rough edge and particulate frosted glass aspect classified as Streptococcus mutans. Under microscopic examination the Streptococcus mutans appeared as Gram positive cocci arranged in chains. Biochemical tests such as the catalase test, hemolysis on blood agar and positive fermentation with sorbitol and mannitol were performed for verification of Streptococcus mutans.24

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were investigated with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. The bacterial count data was log transformed. The results displayed a parametric distribution; thus, they were described as mean and standard deviation (M ±SD). The two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate the impact of different variables and their associations. The one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used to investigate the main effects. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05 for all tests. Statistical analysis was performed with the use of IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v. 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

Results

Radiodensity assessment results

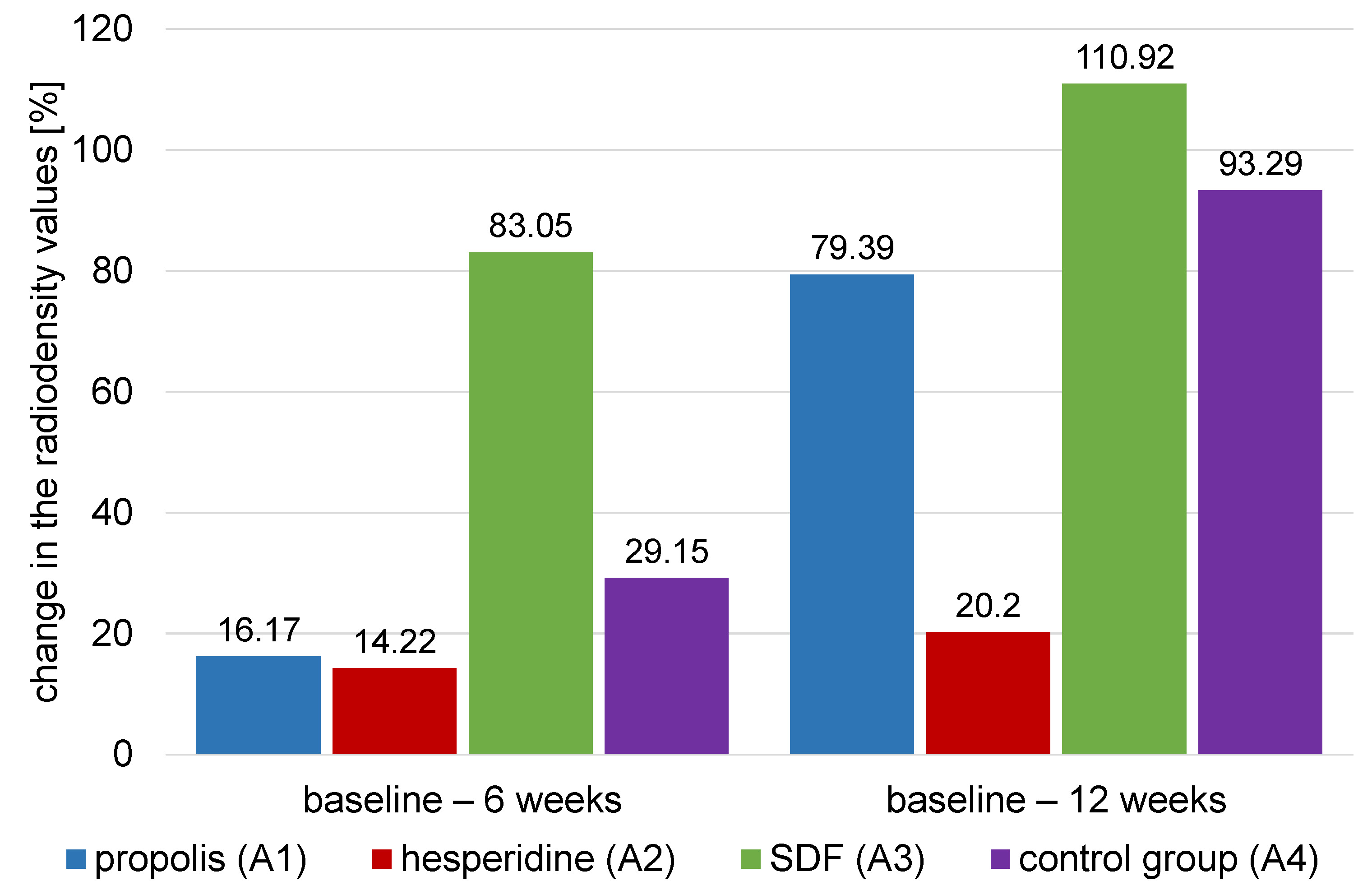

The comparison of the mean percentage changes in dentin radiodensity for different agents within each time interval (ΔT) is presented in Table 3 and Figure 7.

Baseline to 6 weeks (ΔT1)

Results of the ANOVA test showed that there was a significant difference between values of different groups (p < 0.001). Silver diamine fluoride (A3) had the highest (83.05 ±8.78) value of percent change of dentin radiographic density followed by control group (A4) (29.15 ±5.23) then propolis group (A1) (16.17 ±2.79), with the hesperidin group (A2) (14.22 ±2.53) having the lowest value. Tukey’s post hoc test comparison showed that the value for SDF group (A3) group was significantly different from that of the other materials. It also showed that hesperidin group (A2) was significantly different from that of other groups except propolis (A1) (p < 0.001).

Baseline to 12 weeks (ΔT2)

Results of the ANOVA test showed that there was a significant difference between values of different groups (p < 0.001). SDF group (A3) had the highest (110.92 ±8.55) value of percent change of dentin radiographic density, followed by the control group (A4) (93.29 ±7.57), then the propolis group(A1) (79.39 ±9.68), with the hesperidin group (A2) having the lowest value (20.20 ±5.53). Tukey’s post hoc test comparison showed that the values of all groups were significantly different from each other (p < 0.001).

Microbiological results

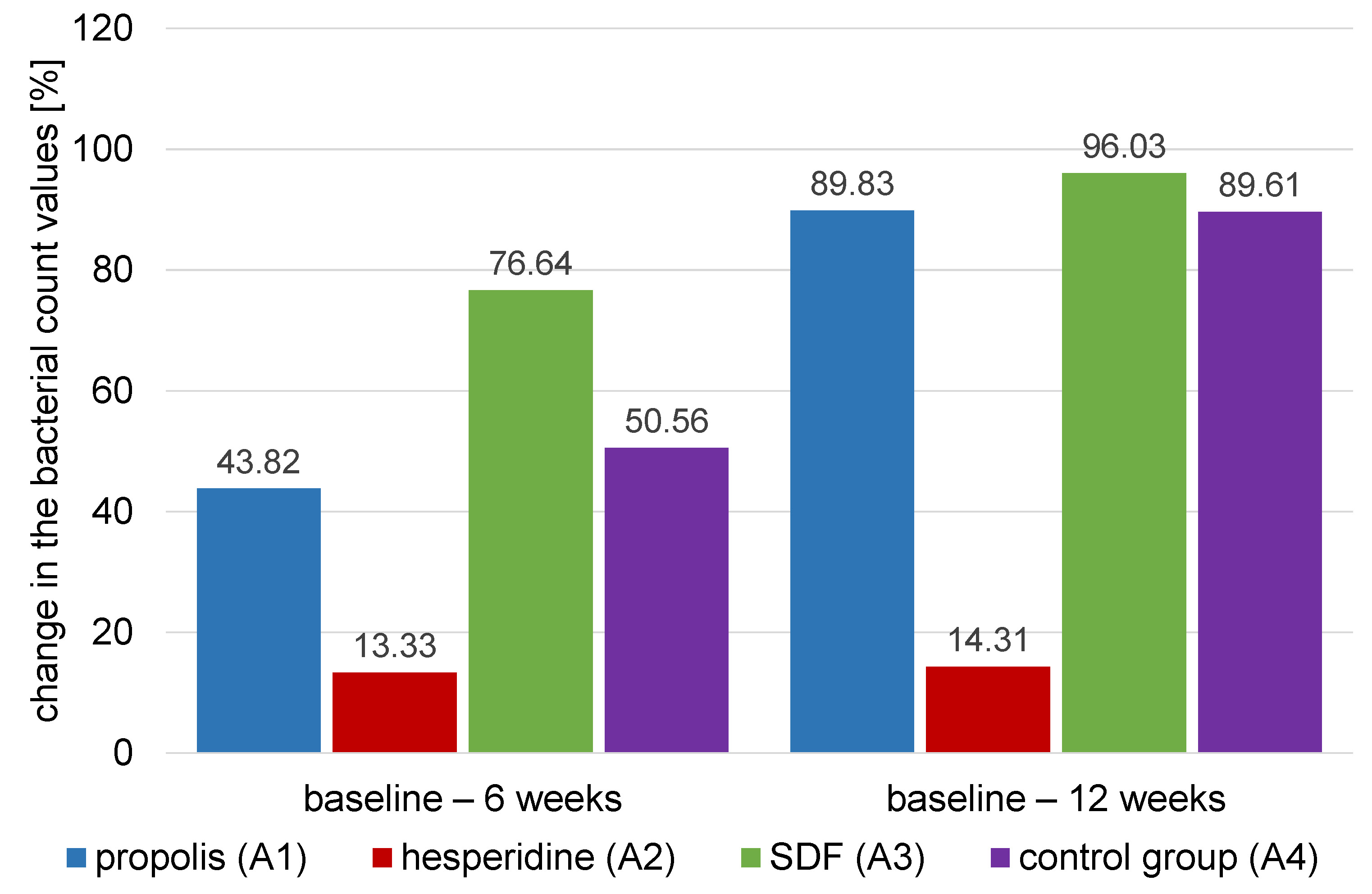

The comparison of the percentage changes in the log transformed mean values for bacterial count (CFU/mL) of different treatment agents within different time intervals is presented in Table 4 and Figure 8.

Baseline to 6 weeks (ΔT1)

Results of ANOVA test showed that there was a significant difference between the values of different groups (p < 0.001). The highest percentage change of the log transformed mean values for bacterial count (CFU/mL) was found in the SDF group (A3) (76.64 ±6.75) group, followed by the control group (A4) (50.56 ±6.47), then the propolis group (A1) (43.82 ±6.56), and finally the hesperidin (A2) group (13.33 ±4.60). Tukey’s post hoc test comparison showed that the percentage change in the log transformed mean values for bacterial count (CFU/mL) of SDF group (A3) was significantly higher than all the other groups. It also showed that hesperidin group (A2) was significantly lower than all other groups except the propolis group (A1). Finally, the propolis group (A1) and the control group (A4) were not significantly different from each other (p = 0.001).

Baseline to 12 weeks (ΔT2)

Results of the ANOVA test showed that there was a significant difference between values of different groups (p < 0.001). The highest percentage change in the log transformed mean values for bacterial count (CFU/mL) was found in the SDF group (A3) (96.03 ±2.68) group, followed by the propolis group (A1) (89.83 ±6.14), the control group (A4) (89.61 ±7.80), and finally the hesperidin group (A2) (14.31 ±4.03). Tukey’s post hoc test results showed that hesperidin group (A2) had a significantly lower value than the other groups (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This work was devised to evaluate the remineralizing and antibacterial effect of propolis and hesperidin versus that of silver diamine fluoride in deep carious dentinal lesion. Subjects were randomized to different treatment groups to ensure the internal validity of comparisons between novel treatments.25

The remineralizing and antibacterial effects of these compounds was evaluated at two separate intervals (6 and 12 weeks). This enabled us to monitor the initial mineral gaining and antibacterial activity in the four test groups, and remineralization of infected dentin remaining after stepwise excavation, respectively. These time intervals were picked to minimize the risk of deterioration of the short-term temporary restoration and patient dropout.13

The pixel grey measurement in digitized radiograph method was used to assess remineralization. A study by Mittal et al. reported that the average pixel grey value can be used to quantitatively monitor caries remineralization, this is based on remineralization being a slower process than demineralization.26

Colony forming unit (CFU) is a measure of viable bacterial cells. For convenience, liquid data are expressed in CFU/mL (colony-forming units per milliliter) and solid findings in CFU/g (colony-forming units per gram). This method is useful to determine the microbiological load and magnitude of infection in any samples.27 After removal of the superficial dentin, samples of carious dentin were taken, to ensure that microorganisms were from the body of the lesion and not dental plaque.28

Propolis (bee glue) is one of many herbal products that possess antibacterial properties. Propolis promotes dental pulp regeneration by preventing microbial infection, inflammation, and pulp necrosis.29 The antimicrobial activity of propolis is derived from its flavonoids, phenolic acids, and phenolic acid esters which can interfere with bacterial cell membranes and cytoplasm, and suppress DNA synthesis.30 Additionally, it promotes stem cells to create an effective tubular dentin.29 Propolis was selected in this study as it is safe for human application, inexpensive, and accessible.

Similarly, hesperidin, a natural flavonoid, is the most active compound of orange fruit and is found in the peel and pulp of the fruit. It consists of a glycogen sugar part bound to the non-sugar part called aglycone. It was used in this study to induce remineralization, antibacterial activity, and arrest active carious dentin.31 Hesperidin was mixed with distilled water due to its higher solubility, which is important for the therapeutic action of the pure powder due to the presence of hydroxyl rings.31 In this clinical trial, remaining carious dentin was capped by natural materials during the whole assessment period. This is supported by the findings of a previous study,32 which suggested that keeping propolis in the mouth produced a greater antibacterial effect, resulting in a considerable reduction in the extent of secondary caries.

Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) is another treatment for slowing the course of dental caries. It achieves this through the antibacterial action of silver halting bacterial growth and the acid resistant fluorapatite surface formed by fluoride.33 Silver ions are bactericidal metal cations that limit microbial growth by suppressing and impeding microbial polysaccharide production through the inhibition of glycosyltransferase enzymes. Unfortunately, the silver content of SDF has some undesired side effects; SDF causes discoloration and an unpleasant metallic taste.34

Self-cured highly viscous GIC were used to restore all tested material and were placed over deep carious lesions due to their high sealing ability which is an important factor for the success of the therapy. Additionally, GIC can release fluoride and chemically bond to moist tissue.35

Radio density results revealed that treatment of active carious dentin with different agents (propolis, hesperidin and SDF) had significantly higher mean mineral dentin density values at the different assessment intervals. After 6 weeks, the results showed more mineral density of carious dentin in the SDF group than in other groups (control, propolis, and hesperidin). While an acid attack, it steadily discharges fluoride to constrain pH and form acid-resistant fluorapatite.31 This is important given the involvement of silver ions, high fluoride content, and chemical reaction with the residual hydroxyapatite in carious dentin. One of the reactions’ byproducts is calcium fluoride (CaF2), which behaves as a fluoride storage.36, 37

Fluoride ion is more similar to the crystal structure of hydroxyapatite than the hydroxyl group is. As a result, fluoridated apatite has a lower solubility than fluoride-free apatite. Consequently, it promotes remineralization by precipitating calcium and phosphate ions, as well as by increasing the precipitation of fluoride apatite above the critical pH.38, 39 In addition, it can protect the organic matrix of dentin in two different ways. First, mineral crystals can protect collagen molecules by binding to calcium binding sites, resulting in less depleted collagen fibers. Second, fluoride ion is a powerful inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases 2, 8, and 9. Fluoride has also been shown to inhibit cathepsins B and K which are required for MMP activation.39

Aside from the fluoride ion mechanism of action, SDF is an alkaline solution with acidity 10.39 This state promotes the association of covalent bonds between phosphorus ions and collagen molecules, which are required for collagen protection.37

The control group (restored only with GI) showed higher mineral carious dentin density over 6 weeks compared to baseline than other natural agents, but it was less effective than SDF. This is directly attributable to the release of fluorine from the glass ionomer cement. Moreover, sealing the cavities with glass ionomer or another restorative material may lead to arresting of caries which is attributed to the absence of bacteria.40

While both hesperidin and propolis showed remineralizing effects on carious dentin, the results from these treatments did not differ from each other. After 6 weeks the propolis group had increased mineral density of carious dentin mainly due to flavonoids present in it that can induce reparative dentin through upregulation of growth factors (TGF-β1) which interact with the extracellular matrix resulting in collagen formation.41, 42 Furthermore, flavonoids can inhibit microorganisms by denaturing proteins and nucleic acids. Hindering of bacteria will decrease demineralization and help in mineral precipitation. Also, the presence of vitamin B complex, pro-vitamin A, arginine, and minerals such as copper, iron, zinc, and bioflavonoids can induce formation of new hydroxyapatite crystals.43, 44

Meanwhile, in the hesperidin group, a non-significant difference in mineral density value of carious dentin and remineralizing effect on carious dentin was observed between the 6 and 12-week periods. This may be the result of the slightly acidic nature of hesperidin, which is obtained from citrus fruits. This low pH media results in low calcium and phosphorus ions participation which reduces remineralizing and the antibacterial effect.31

A study found that the application of standardized propolis extract as a pulpotomy medication caused the formation of a partial mineralized tissue barrier after 21 days, and a complete calcified bridge after 42 days.45 Meanwhile, SDF showed the same action in less time with a high amount of fluoride and silver halt active carious lesions and provide antibacterial action. Our findings agree with another study,41 which compared the remineralizing and antibacterial effect of SDF and propolis. It was found that SDF had superior antibacterial and remineralizing ability, which was attributed to the concentration of active ingredients in SDF that reach up to 38%, as opposed to propolis fluoride which only contains 10% active material. Our clinical trial results showed a decrease in bacterial total counts over the different assessment periods compared to baseline data in active carious dentin lesions treated with natural or synthetic agents.

After 6 weeks, the SDF group had the greatest reduction in bacterial counts, followed by the control and propolis groups respectively. SDF likely had the greatest antibacterial effect because of the presence of silver and fluoride ions. Antimicrobial activity of silver ions can be attributed to several factors; when silver ions react with the thiol group of enzymes, they deactivate the enzymes which then cause bacterial death.46, 47 These silver ions could also interact with bacterial cell DNA, which can cause mutations in the DNA and bacterial cell death. Furthermore, silver binds to the anionic parts of the bacterial cell membrane which can cause bacterial death. Silver can also create a protein-metallic combination with amino acids, which then can concentrate within the bacterial cell rendering bacterial DNA and RNA inactive.15 Our data is in line with an earlier study,48 which found that SDF’s effectiveness in arresting pre-existing dentin caries and preventing new caries was due to the synergistic effect of silver and fluoride ions in inhibiting cariogenic bacterial growth, remineralization, and organic matrix protection.

Restoration of active carious dentin with GIC only, without any treatment, showed a significant decrease in the total bacterial count. This could be due to the fluoride released by conventional GIC restoration. Fluoride ions can promote remineralization, inhibit cariogenic bacterial growth and enhance the calcification of demineralized dentin after curettage.49

Total bacterial count in active carious lesions was decreased when using propolis. Propolis can prevent bacterial proliferation and inhibit bacterial protein synthesis which can cause partial lysis.46 Propolis constituents such as pinocembrin and naringenin also possess antibacterial activity.47

Silver ions can inactivate and interfere with bacterial growth by inactivating glycosyltransferase enzymes, which are needed for glucan synthesis. Glucan is required for bacteria sucrose-dependent adhesion to tooth surfaces.48, 49, 50

In the present work, there was a significant difference between the natural agent propolis and the synthetic agent SDF, which was attributed to the natural agents needing more time. This may be due to the concentration of active ingredients being lower in the natural agent.51 Propolis and hesperidin are natural materials which may mean that they have increased safety and fewer side effects compared with synthetic products. Therefore more clinical trials are required to investigate differences in the efficacy between natural and synthetic materials.

Finally, in the present study, the first null hypothesis that there is no difference between natural and synthetic agents on the remineralizing potential of carious dentin was rejected. We found that there was a statistically significant difference between each material. In addition, the second null hypothesis that there is no difference between natural and synthetic agents as antibacterial agents was partially accepted as we found that there was a statistically significant higher percent change of bacterial count for propolis and SDF compared with hesperidin.

Conclusions

Propolis may be a promising substitute for synthetic remineralizing and antibacterial agents. Silver diamine fluoride has powerful antibacterial and remineralizing effect. Marginal seal seems to be a crucial factor in the management of deep carious dentin.

Recommendations

Further clinical trials are required to evaluate the pulpal outcome against the applied materials. Further clinical trials also are required to investigate the clinical performance of other natural materials.

Trial registration

The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under the identification number NCT04145102.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at the Faculty of Dental Medicine for Girls of Al-Azhar University (REC-OP-21-05). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the commencement of the study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.