Abstract

Background. With the development of medicine and extending the human lifespan, the next challenge for healthcare providers is to improve the quality of life. Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) is a worldwide known questionnaire that is used for assessing oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL).

Objectives. The aim of the present study was to assess the impact of periodontal diseases, oral mucosal lesions and dental caries on OHRQoL among Polish adults.

Material and methods. A cross-sectional study consisting of an intraoral clinical examination and a questionnaire was conducted among 250 adult patients seeking dental treatment at the University Dental Clinic (UDC) in Cracow, Poland. The obtained clinical data included the number of decayed, filled and missing teeth (DMFT), the presence of fixed or removable dental prostheses, the type and size of oral mucosal diseases, periodontal data based on a visual examination as well as the approximal plaque index (API) and modified sulcus bleeding index (mSBI) scores, and the patient’s dental history. A modified OHIP questionnaire was used, which had been previously validated amongst patients with periodontal and oral mucosal diseases.

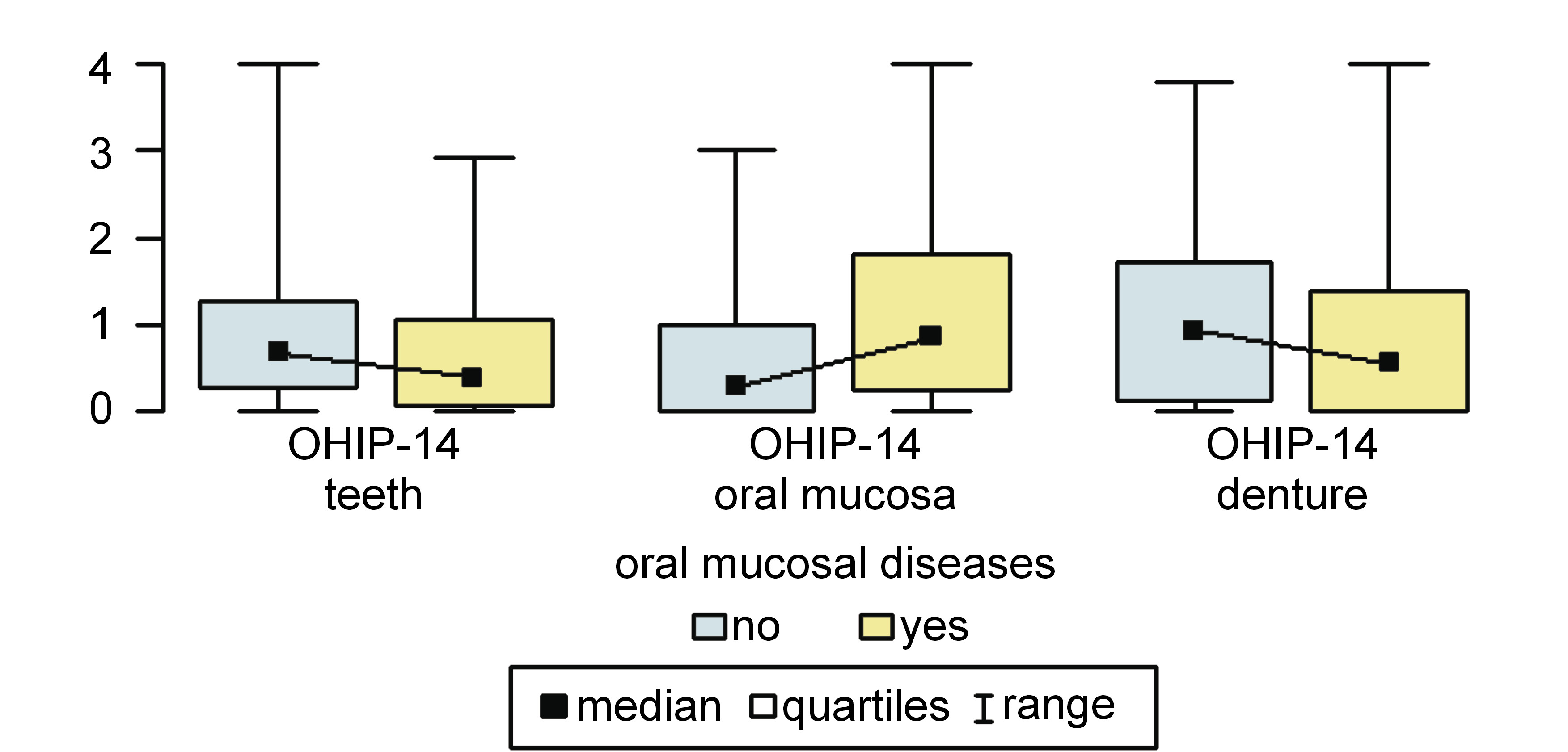

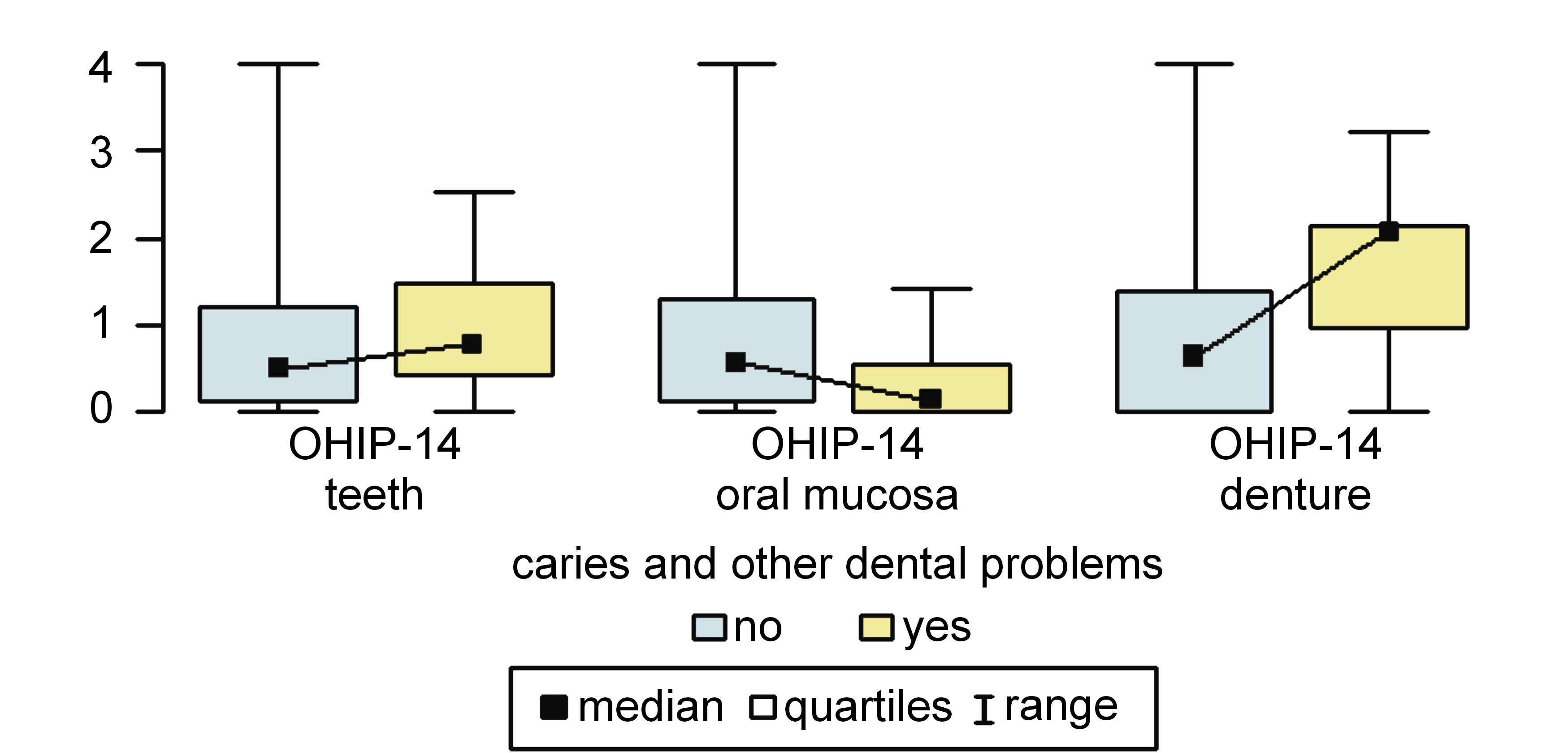

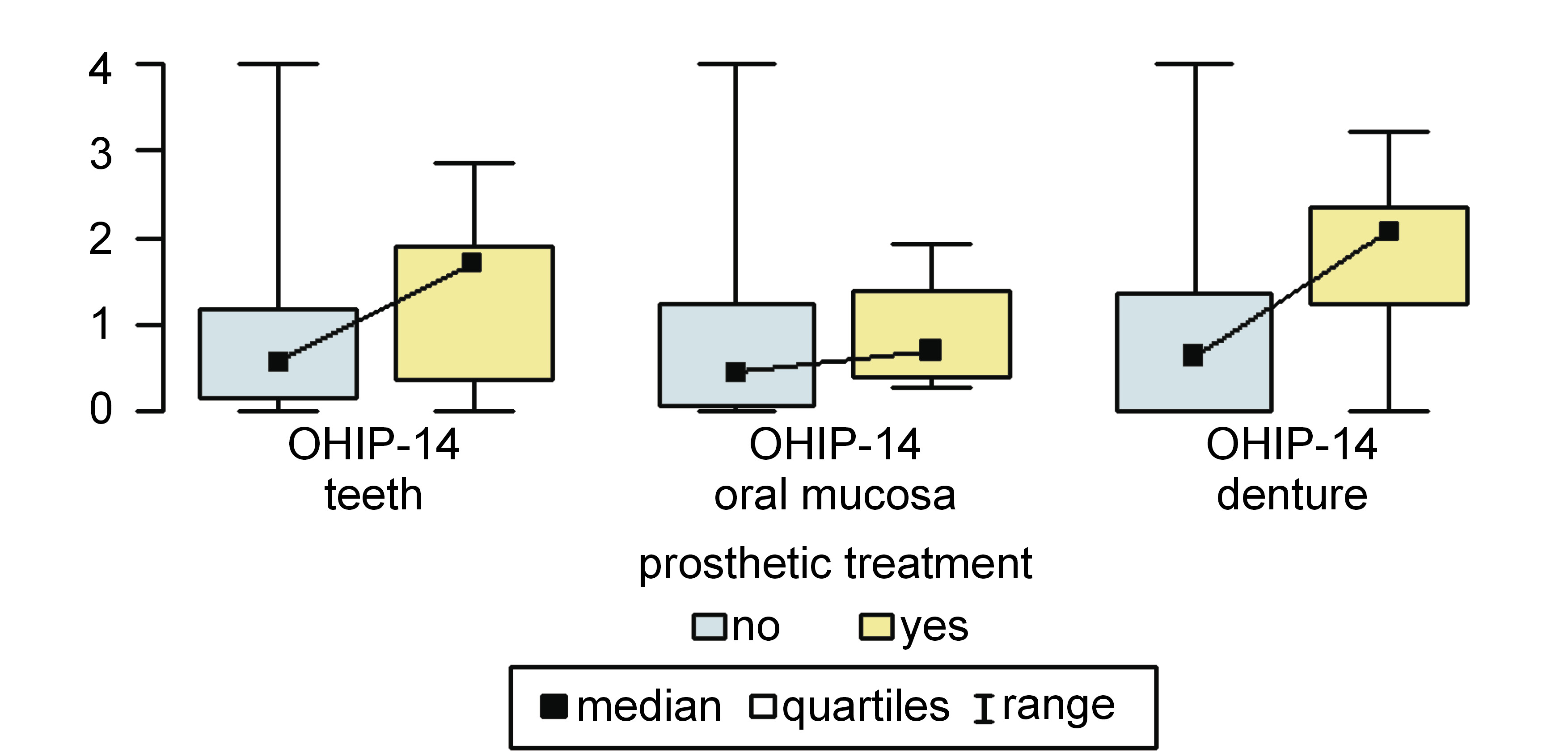

Results. In patients reporting problems with oral mucosa, the OHIP-14 scores in relation to oral mucosa and other soft tissues were higher, and the scores in relation to the teeth were lower than in patients who did not suffer from oral mucosal diseases (0.86 (0.25–1.81) vs. 0.29 (0–1.00); p < 0.001, and 0.39 (0.07–1.07) vs. 0.68 (0.29–1.29); p = 0.048, respectively). Among patients looking for treatment due to caries and other dental problems, the OHIP-14 scores relating to dentures were higher and the scores relating to oral mucosa were lower than in patients who did not report such problems (2.07 (0.96–2.15) vs. 0.64 (0–1.38); p = 0.043, and 0.14 (0–0.56) vs. 0.57 (0.14–1.31); p = 0.001, respectively). Among patients noticing prosthetic problems, the OHIP-14 scores relating to dentures were higher than in those who did not suffer from such issues (2.07 (1.23–2.36) vs. 0.64 (0–1.36); p = 0.004).

Conclusions. The symptoms reported by patients with periodontal diseases, oral mucosal lesions and dental caries influenced their OHRQoL. The proper prophylaxis and treatment of these diseases are important to avoid the worsening of OHRQoL.

Keywords: periodontal diseases, oral mucosal diseases, caries, OHIP-14, OHRQoL

Introduction

With the development of medicine and technology, leading to the extension of the human lifespan, the subsequent challenges for healthcare providers in dentistry are to advance diagnostic processes and consider patient well-being. Medical and dental history, a clinical examination, and additional diagnostic tests (e.g., radiography, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), ultrasound imaging, and dental photography) allow the dentist to make an adequate diagnosis and plan alternative treatment options.1, 2, 3 Furthermore, simulating the possible treatment outcomes may be advantageous for patient psychological well-being4 and may improve patient–dentist communication. It is particularly important for dentists to consider the development of technologies and devices in each field of dentistry. The use of modern appliances may help to reduce the dose of radiation emitted during the examination and decrease the biological risk related to ionizing radiation.5 The development of non-invasive diagnostic methods, such as ultrasonography (USG), can also help to minimize biological risk to the patient. Owing to scientific progress, it has become possible to overcome the existing limitations of some examinations, and new indications for their use have emerged. Ultrasonography seems to be the best tool for use in the differential diagnosis of bone lesions, such as periapical lesions or tumors,6, 7, 8 and may be useful in planning periodontal and peri-implant surgeries, or for evaluating the stability of tissues after such procedures.5, 9, 10 Furthermore, USG may be an additional tool for the examination of disc displacements in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).11 The gold standard examination with regard to a disc displacement in TMJ and its differentiation from other diseases, such as coronoid process hypertrophy,12 is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),13 which is also radiation-free.

In diagnostic and therapeutic processes, the patient’s individual expectations and experience should be taken into consideration in order to respect their well-being. Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) is a complex and multidimensional concept describing the influence of the oral cavity condition on an individual’s well-being and quality of life. To assess OHRQoL properly, it is necessary to use tools developed and validated for a specific population, with regard to its age, native language and diseases. Until now, many such questionnaires in many language versions have been developed for use in children (e.g., Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS),14, 15, 16, 17 Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ)18, 19, 20), adolescents (Oral Impact on Daily Performance (OIDP)21, 22) and adults (Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP),23 Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI),24, 25 Liverpool Oral Rehabilitation Questionnaire (LORQ),26 the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) assessment tool27).

The OHIP is a worldwide known questionnaire used for assessing OHRQoL. It was developed and validated in 1994 by Slade and Spencer to investigate the social impact of oral disorders on well-being.23 Initially, the questionnaire consisted of 49 items (OHIP-49), but to facilitate its usage in clinical settings, Slade created a shortened version (OHIP-14) that has been shown to be as reliable as the primary form.28 The OHIP-14 captures 7 dimensions that have affected people’s life and health over the previous 12 months. This includes functional limitations, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap.28 Each dimension is determined by 2 items (yes/no); for example, it may ask participants if they have had any trouble pronouncing any words because of problems with their teeth, mouth or dentures.

To adapt the OHIP questionnaire to other populations, the original English version was translated into other languages, including Polish,29 Spanish,30 Greek,31 Turkish,32 and Korean,33 adapted and validated.

Until now, the link between many specific oral disorders, such as caries,34, 35, 36, 37, 38 oral mucosal diseases,39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 periodontal diseases,36, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 tooth wear,56, 57 tooth loss,58, 59 and temporomandibular disorders (TMD)60, 61, and general diseases, including diabetes,51, 53 rheumatic diseases,62 leukemia,63 and renal diseases,64 and OHRQoL has been thoroughly researched among adults.

The aim of this study was to appraise the impact of periodontal diseases, oral mucosal lesions and dental caries on OHRQoL among Polish adults looking for treatment at a specialized university clinic.

Material and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 250 adult patients seeking dental treatment at the Department of Periodontology, Dental Prophylaxis and Oral Pathology of the University Dental Clinic (UDC) in Cracow, Warsaw. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Jagiellonian University Medical College in Cracow (No. 122.6120.354.2016). The patients were given detailed information on the study and informed written consent was obtained from each of the enrolled participants. The exclusion criteria were as follows: under 18 years of age; and the lack of consent for participation in the study.

Data was collected by conducting an intraoral clinical examination and a questionnaire survey. Clinical data was obtained through an examination conducted by one dentist, using artificial light, a dental mirror and a WHO periodontal probe. The obtained data included the number of decayed, filled and missing (due to any reason, excluding third molars) teeth (DMFT), the presence of fixed or removable dental prostheses, the type and size of oral mucosal diseases, periodontal data based on a visual examination as well as the approximal plaque index (API) and modified sulcus bleeding index (mSBI) scores, and the patient’s dental history. More data was collected from the self-completed quality of life (QoL), OHRQoL and OHIP-14 questionnaires, with the results of the latter being analyzed, and patients were asked about their reasons for visiting the UDC.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the R software, v. 4.1.1 (https://www.r-project.org/).65 The significance level for all statistical tests was set at 0.05. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative and ordinal variables between two groups. The relationship between two quantitative and/or ordinal variables was assessed with Spearman’s coefficient of correlation. Quantitative variables were summarized as median (interquartile range) (Me (IQR)).

Results

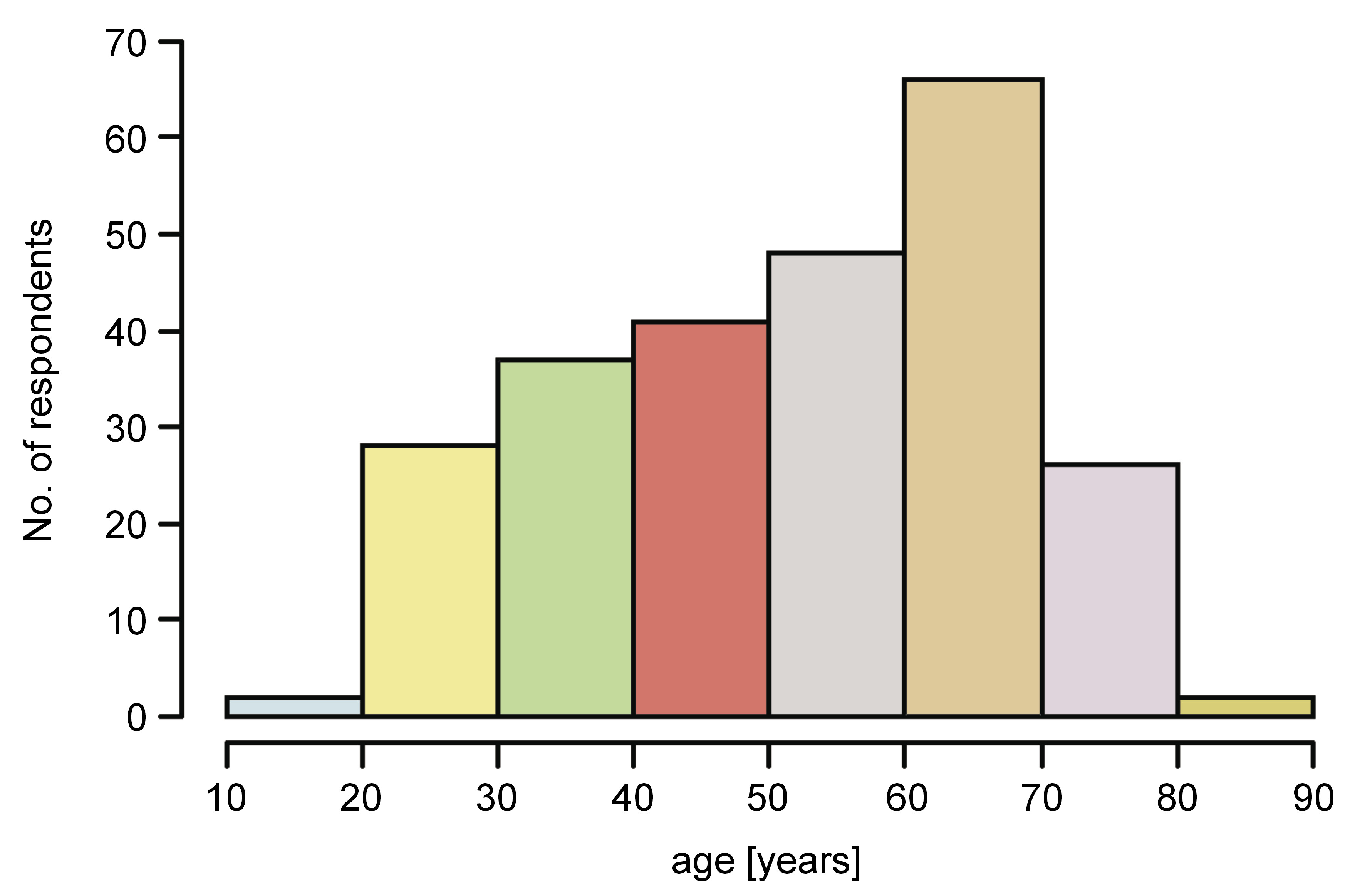

A group of 250 patients was enrolled in the study (age: 18–82 years; mean age: 52.16 ±15.85 years; females: 65.2%) (Figure 1). They all underwent an intraoral clinical examination and self-completed the questionnaire.

A modified OHIP-14 questionnaire was used, which had been validated amongst patients with periodontal and oral mucosal diseases and caries.66 The adjustments involved: 1) asking about all of the items separately in relation to the teeth (subscale 1), oral mucosa and other soft tissues (e.g., gingiva, the tongue) (subscale 2) and dentures (subscale 3); and 2) adding 2 additional answers, i.e., ‘I don’t know’ and ‘not applicable’. The changes were implemented to explore detailed OHRQoL and, according to the authors’ current knowledge, they had never been used before in studies on the OHIP questionnaire.

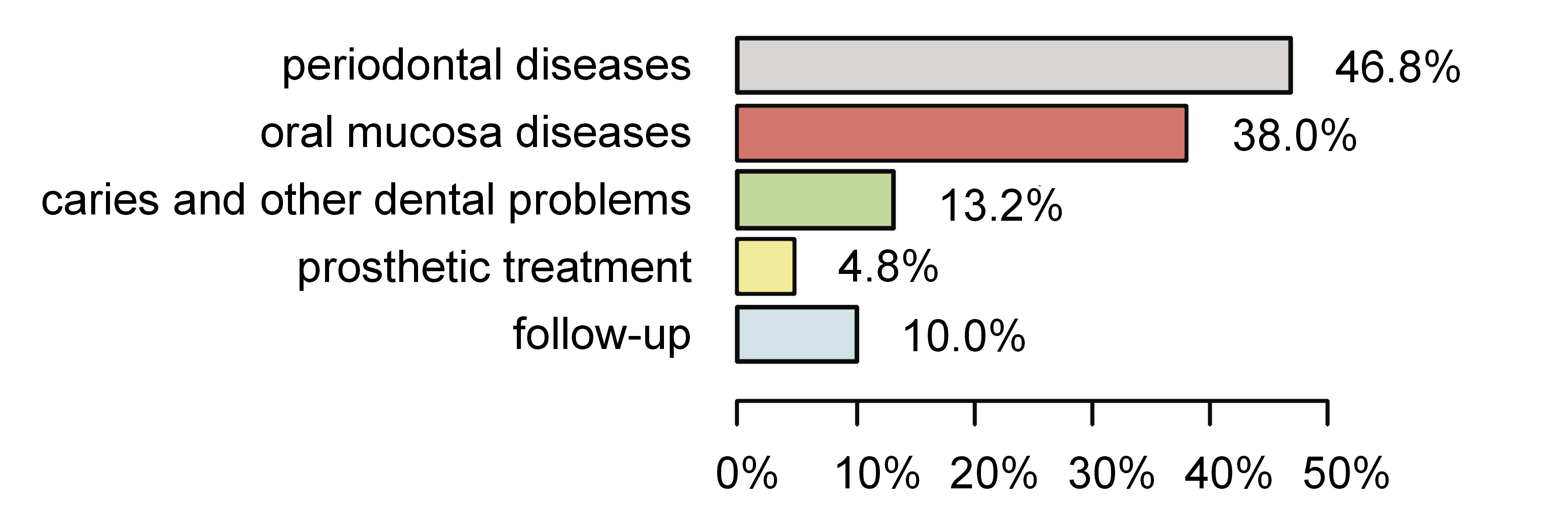

The patients were divided into 5 groups depending on their reason for visiting the UDC: group 1 – periodontal diseases (117 (46.8%)); group 2 – oral mucosal diseases (95 (38.0%)); group 3 – caries and other dental problems (33 (13.2%)); group 4 – prosthetic treatment (12 (4.8%)); and group 5 – follow-up (25 (10.0%)) (Figure 2).

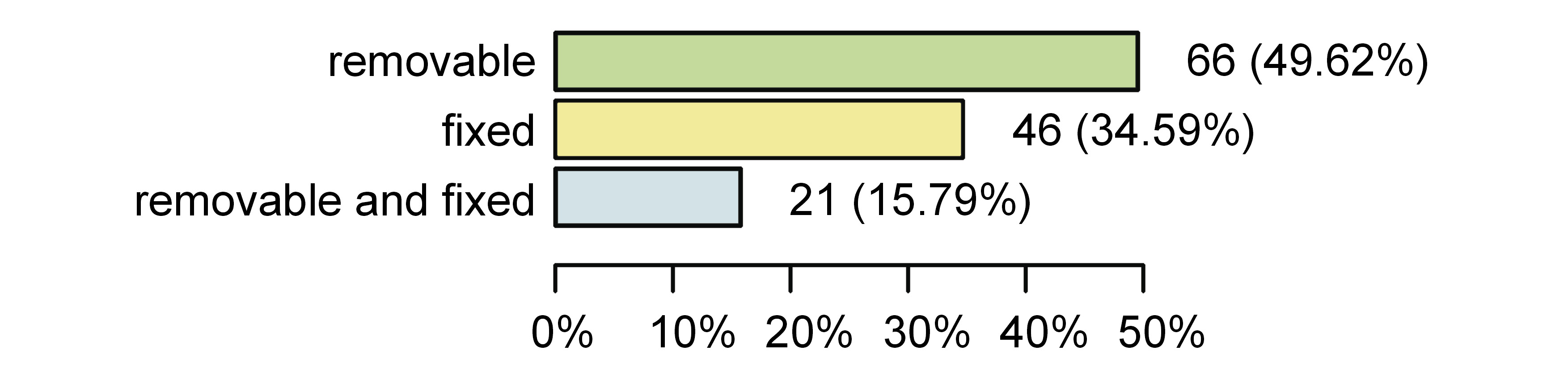

The mean number of missing teeth (due to any reason, excluding third molars) among the respondents was 8.34 ± 8.36, and only 43.7% had all of the missing teeth replaced. The types of prostheses used are shown in Figure 3.

The OHIP-14 items were rated on a Likert-type scale as never (0), almost never (1), sometimes (2), fairly often (3), or almost all of the time (4). The scale referred to the frequency of the occurrence of the symptoms or problems related to the teeth (subscale 1), oral mucosa (subscale 2), or dentures (subscale 3). The higher the OHIP-14 score was, the worse OHRQoL was assumed.

There was a significantly higher subscale 2 score and a significantly lower subscale 1 score in group 2 than in any other group (0.86 (0.25–1.81) vs. 0.29 (0–1.00); p < 0.001, and 0.39 (0.07–1.07) vs. 0.68 (0.29–1.29); p = 0.048, respectively (Figure 4). There was no significant difference in the OHIP-14 scores within subscale 3 between these groups of respondents.

Patients suffering from caries and other dental problems (group 3) had a significantly higher OHIP-14 score within subscale 3 and a significantly lower score within subscale 2 as compared to other respondents (2.07 (0.96–2.15) vs. 0.64 (0–1.38); p = 0.043, and 0.14 (0–0.56) vs. 0.57 (0.14–1.31); p = 0.001) (Figure 5).

In group 4 (patients looking for prosthetic treatment), the OHIP-14 score within subscale 3 was significantly higher than among other patients (2.07 (1.23–2.36) vs. 0.64 (0–1.36); p = 0.004) (Figure 6).

In group 1 (patients with periodontal diseases) and group 5 (follow-up), there were no statistically significant differences observed within any subscale in comparison with other participants (p > 0.05).

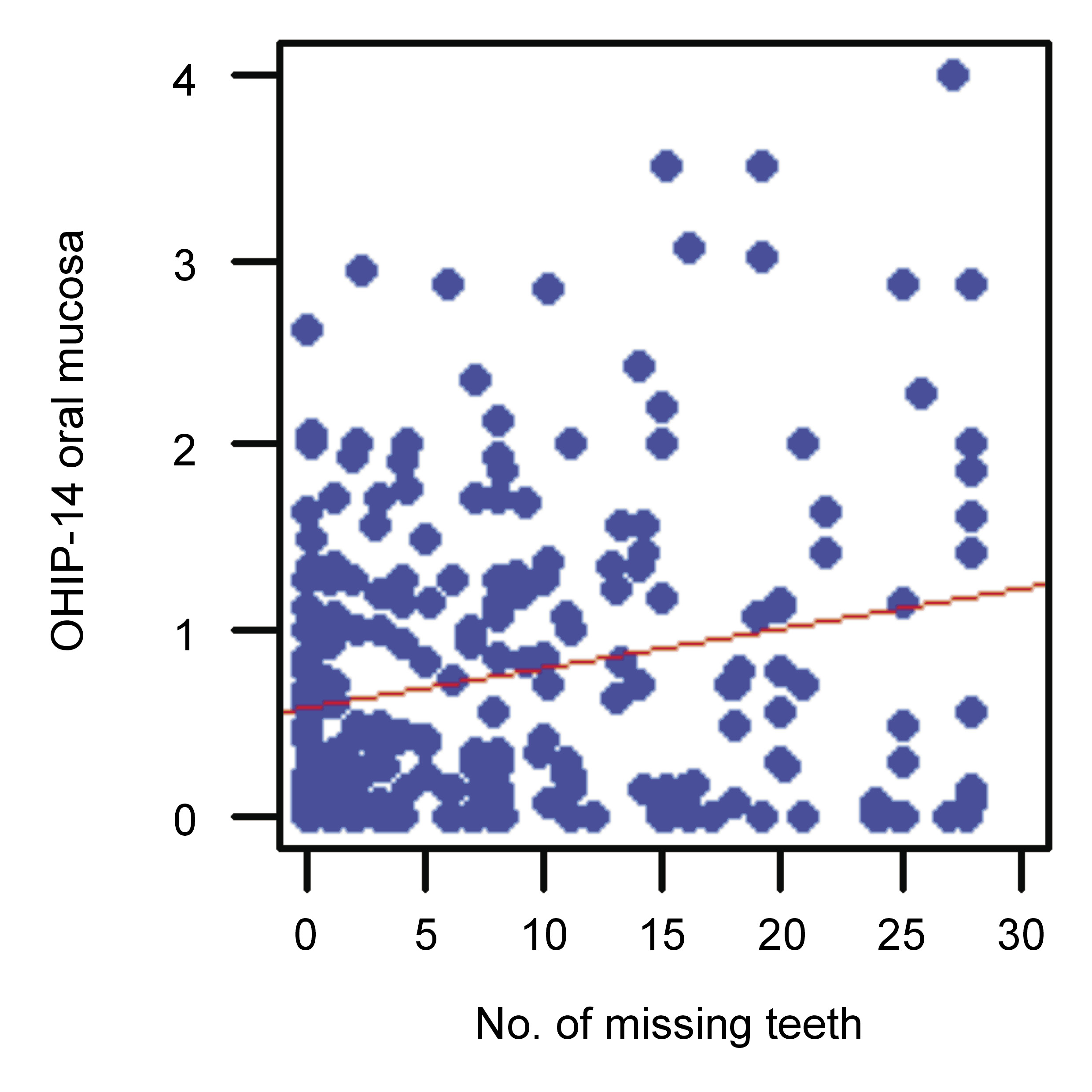

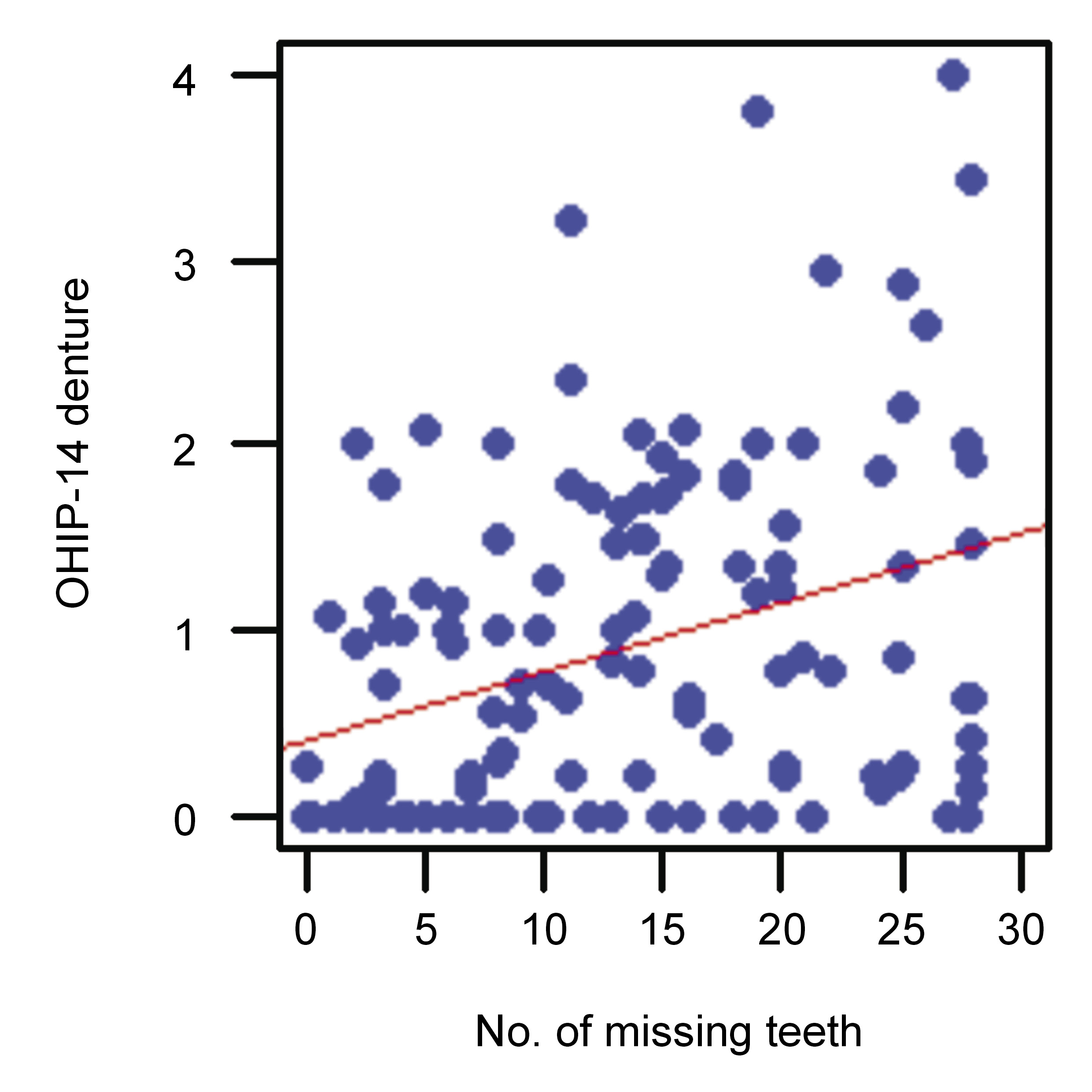

There was a statistically significant (p < 0.05) positive correlation (r > 0) between the number of missing teeth and the OHIP-14 scores within subscales 2 and 3 (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Discussion

The most prevalent oral diseases are dental caries, periodontal diseases, tooth loss (having 9 or fewer teeth),67 and cancers (of the lips and of the oral cavity).68 They remain a significant global public health concern and have a serious socio-economic impact.68, 69 This is especially true in low-income and middle-income countries, where the prevalence of these diseases remains high and the financing of oral healthcare is low.68, 70 Untreated oral diseases have many negative consequences on personal life, including suffering from pain, impaired quality of life, school absenteeism, and decreased productivity at work.68

Dental caries is a multifactorial disease involving interactions between the hard tissues of the tooth, the biofilms formed on the tooth surface, and sugars that cause tooth demineralization.71 The disease is conditioned by genes and the salivary flow.71 It occurs in 60–90% of children and in nearly 100% of adults.70 Caries may occur in children under 6 years of age, in their deciduous teeth, and is called early childhood caries (ECC).71, 72 In epidemiological studies, the international decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) index is used for assessing caries at the individual and population level.71 Caries is preventable and the application of preventive measures generates significantly lower costs than the treatment of the disease.71, 73 Such measures include proper oral hygiene (tooth brushing and interdental hygiene), the daily and professional use of fluoride, the reduction of the amount and frequency of sugar intake, saliva stimulation, and the use of antibacterial agents.71, 73, 74 Biofilm engineering, through the use of pre- and probiotics, seems to have a long-term anti-cariogenic effect.73

The most common periodontal disease is periodontitis. This is an inflammatory, chronic and multifactorial disease that leads to the destruction of connective tissue and the bone supporting the teeth, and is a result of interactions between host inflammatory immune responses and the bacterial biofilm.75, 76, 77 Untreated periodontal disease leads to bacterial dysbiosis, calculus deposits and periodontal pockets. It may be manifested by bleeding gingiva,78 tooth mobility and the eventual tooth loss, halitosis, and the worsening of oral and dental esthetics. It all causes functional and social difficulties while biting, chewing and speaking, which eventually worsen OHRQoL77, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83 and systemic health.77, 78 By activating inflammatory pathways, periodontitis may influence well-being and health during pregnancy, and can lead to complications such as preeclampsia, which is one of the major causes of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality,84 premature delivery, and low birth weight.85, 86 Lipopolysaccharide is one of the most virulent factors of the anaerobic bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis that is present in periodontitis,87 and it may affect gene expression and diverse cellular processes by increasing the levels of microRNA-155.85, 86 Mahendra et al. suggested that the levels of microRNA-155 could be a genetic diagnostic tool for the rapid identification of preeclampsia.86

Studies have shown that generalized forms of periodontitis have a greater impact on OHRQoL than localized88 and more severe forms.49, 79, 89 Oliveira et al. demonstrated that periodontitis had similar effects on OHRQoL to general diseases, such as end-stage renal disease.89 Other periodontal diseases that negatively affect OHRQoL are gingivitis and gingival recession.83, 90 Most of the patients in this study suffered from chronic forms of periodontitis, which may progress gradually throughout the years. However, unless any exacerbation (e.g., a periodontal abscess) occurs, the patient may not observe any major changes. Of the respondents in this group, 55.3% were continuing treatment, which means that acute complaints had already been mostly treated. The results showed slight differences in the subscale 1 OHIP-14 scores among periodontal patients, but they were not statistically significant (p = 0.054).

Systemic diseases, especially those with a pro-inflammatory component (e.g., type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases), are a risk factor for the initiation and progression of periodontitis.67, 70 Indeed, periodontitis has been declared the 6th most frequent complication of diabetes mellitus.91 Periodontitis and systemic chronic diseases have the same fundamental risk factors,78 including tobacco use, poor oral hygiene, and dietary and lifestyle behaviors.67

The basis of periodontal therapy is regular home care, and professional subgingival plaque and calculus removal, which is called non-surgical therapy.92 There may be indications for the use of adjunctive measures to improve periodontal health, such as topical antimicrobial agents, antibiotics, antiseptics, or host-modulating drugs.92, 93 With regard to the latter, a recently conducted systematic review suggests that the topical or systemic administration of melatonin might be useful for the management of periodontitis.93 Furthermore, non-surgical periodontal treatment improves OHRQoL by reducing pain, psychological discomfort and physical disability.55, 94

Tooth loss is a serious impairment that causes functional problems while eating, and thus deterioration in OHRQoL.95 Comparing studies conducted in the 1980s and 1990s with the current work, there is a positive trend showing a reduction of edentulism in the Danish population (17.7% vs. 3.4%).96 However, these values remain much higher in developing countries, where dental healthcare is limited to emergency care.70 Tooth loss may be a consequence of caries or a periodontal disease.70 Therefore, access to dental healthcare, regular dental visits, and patient education about disease prophylaxis and their compliance are some of the factors that can reduce the risk of tooth loss.

Nowadays, and particularly following the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, telemedicine is rapidly developing, enabling patients to keep in contact with healthcare workers. This allows the detection of the early symptoms of the disease or the worsening of the health condition.97 Social media are widely used, especially by younger people, and they may prove advantageous to develop appropriate and valuable health content on such platforms, and thus to broaden patient knowledge about prophylaxis and the proper treatment of oral and general diseases.98, 99

Oral mucosal diseases comprise many disorders, such as oral leukoplakia (OL), oral erythroplakia (OE), burning mouth syndrome (BMS), oral lichen planus (OLP), oral submucous fibrosis (OSF), xerostomia, candidiasis, Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), and autoimmune bullous diseases. Some of them (OL, OE, OLP, OSF, and oral epithelial dysplasia) are considered as potentially premalignant oral epithelial lesions (PPOELs)100 or oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs),101 of which leukoplakia is the most frequently occurring.70 The rate of their malignant transformation to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) varies depending on the type and site of the lesion, and it is the highest for OE, with an average of 26.3% (ranging from 14.3% to 50.0%).102 It is important to emphasize that prevention, early detection and treatment may halt malignant transformation to OSCC.100, 103 The main risk factors for developing OPMDs and their malignant transformation are tobacco and alcohol use. Depending on the type of disease, its severity and course (active or inactive), the reported symptoms may be more painful for the patient,39, 104 may have a social impact42 or may reduce the secretion of saliva, as observed in SS,105 all of which eventually worsen OHRQoL.39, 41 The proper treatment of these complaints may decrease pain and anxiety, and improve OHRQoL.106, 107 In this cross-sectional study, the OHRQoL of the group of patients with oral mucosal diseases was most influenced by their oral mucosal disease. In other patients, OHRQoL was affected to a greater degree by the condition of their teeth. This means that oral mucosal diseases are perceived by patients as much more serious and that they may affect their life in multiple ways.

In patients looking for restorative or prosthetic treatment, the use of dentures significantly worsened OHRQoL. In this study, almost half of the patients were using removable prostheses and 34.59% had only fixed dentures. The UDC is a specialized clinic in which most patients are treated within the National Healthcare Fund, which only refunds acrylic dentures. Nonetheless, prosthetic treatment improves OHRQoL regardless of the treatment used.108 Fixed tooth-supported dentures are set on the teeth, which need appropriate preparation, so it is important to properly assess the condition of the teeth before prosthetic treatment to avoid complications and failures. A significant advantage of such an approach is the reduction of prosthesis extension and the preservation of bone volume. Removable dental prostheses are supported on crowns (e.g., cast partial dentures, overdentures109). They can be carefully cleaned outside the mouth and can have teeth added. This may be important for older people with decreased fine motor skills, or for periodontal patients, in whom the risk of tooth loss is greater.110, 111 With the use of removable dental prostheses, financial constraints may be overcome; the dentures may also be used as temporary ones.111 Another treatment option are implant-supported fixed or removable prostheses, which expand the prosthetic treatment opportunities. A proper surgical technique and the presence of an implant in the bone may influence bone volume in the short and long term.112 Before prosthetic treatment, all indications, contraindications and patient expectations need to be considered.

Yoshimoto et al. reported a strong association between OHRQoL and masticatory satisfaction (defined as the ability to eat comfortably) among individuals using removable partial dentures,113 whereas Inoue et al. claimed that the quality of removable dentures (stability and esthetics) had a minimal effect on the OHIP score.114 On the contrary, according to Kurosaki et al., only implant-supported fixed dentures improved OHRQoL 6 years after prosthetic treatment, and there was no significant improvement in patients wearing fixed or removable partial dentures.115 Meanwhile, according to Ali et al., both tooth- and implant-supported fixed prostheses positively affected OHRQoL in the short and long term.116

In this cross-sectional study, there was a significant positive correlation between the number of missing teeth and impact on OHRQoL in relation to oral mucosa and dentures. This means that the greater the number of lost teeth, the greater the problems for the patients referred regarding their oral mucosal disease and denture use, and the greater the necessity for a dental visit.

Conclusions

To prevent the worsening of OHRQoL, the proper prophylaxis of caries and its complications (pain, tooth destruction and extraction) is very important. It delays any need for prosthetic treatment. Proper patient education, prophylaxis and treatment of oral mucosal diseases and periodontal diseases are crucial for the preservation of OHRQoL.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jagiellonian University Medical College in Cracow, Poland (No. 122.6120.354.2016). Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.