Abstract

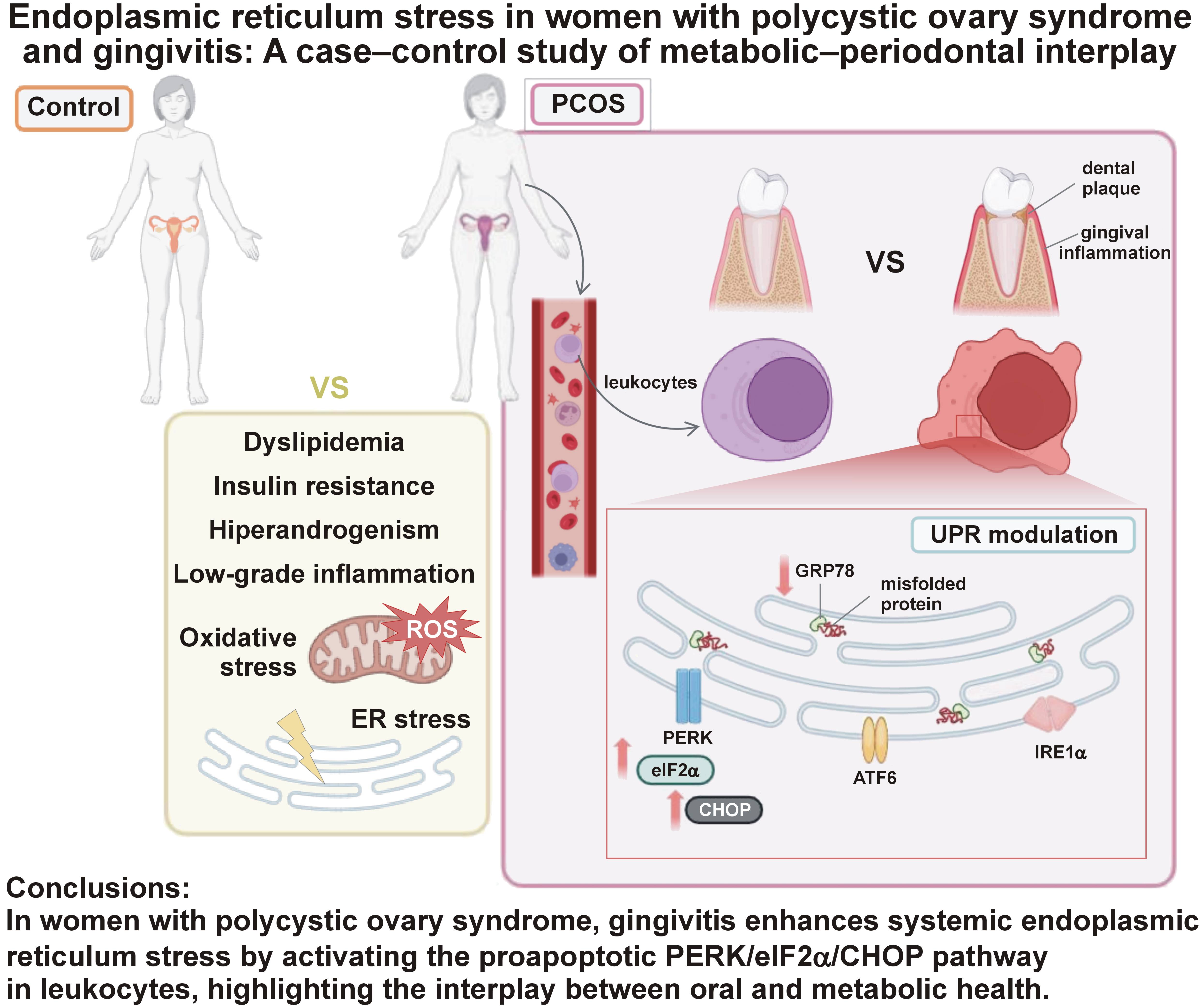

Background. Gingival inflammation has been increasingly linked to metabolic and endocrine disorders, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). This connection may involve immune system activation and cellular stress mechanisms, particularly the unfolded protein response (UPR), which regulates endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to investigate whether gingivitis modulates UPR activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of women with PCOS.

Material and methods. In this case–control study, female subjects were divided into 2 groups: a control group (n = 48); and a PCOS group (n = 68), which included 24 individuals with gingivitis (PCOS+). Anthropometric, biochemical and periodontal parameters were determined, namely probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment level (CAL), bleeding on probing (BOP), and plaque index. Markers of oxidative stress, including total superoxide and glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1), and UPR mediators, such as glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha subunit (p-eIF2α), and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), were evaluated in PBMCs.

Results. Polycystic ovary syndrome was associated with an increased plaque index and significantly higher BOP in PCOS+. Increased superoxide and reduced GPx1 levels were observed in women with PCOS, with no significant differences between subgroups. Gingivitis in PCOS was correlated with the activation of specific UPR pathways; higher levels of p-eIF2α and CHOP and lower GRP78 levels were detected in PCOS+, while ATF6 was increased in the overall PCOS group. Moreover, BOP demonstrated a direct correlation with p-eIF2α and the plaque index.

Conclusions. The association of leukocyte ER stress responses in PCOS with gingival inflammation underscores the impact of periodontal disease on modulating systemic cellular stress in the context of multifactorial metabolic disorders.

Keywords: endoplasmic reticulum stress, gingivitis, polycystic ovary syndrome, unfolded protein response, oxidative stress

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a hormonal and metabolic disorder that manifests in reproductive-age women and is characterized by hyperandrogenemia, anovulation and multiple ovarian cysts, often causing infertility, irregular menstrual cycles, acne, and hirsutism.1 The condition is also linked to insulin resistance (IR), inflammation and oxidative stress.2, 3, 4 Recent evidence suggests that women with PCOS are more prone to periodontal disease (PD), such as gingivitis and periodontitis,5, 6 probably due to the link between IR and periodontal inflammation.7 Periodontal disease has also been associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, including preterm birth and low birth weight, further highlighting its relevance to women’s reproductive health.8

Gingivitis may arise from a bacterial imbalance within dental plaque (dysbiosis).9 When left untreated, gingivitis can progress to periodontitis, a condition characterized by persistent inflammation of the connective tissues supporting the teeth.10, 11 This ongoing dysbiosis facilitates bacterial spread into the periodontal pockets, leading to leukocyte recruitment and increased local oxidative stress. In advanced stages, periodontitis culminates in irreversible tissue damage and potential tooth loss.11 Beyond oral consequences, both gingivitis and periodontitis have been closely associated with increased cardiovascular risk, which underscores their broader systemic health implications.12

While oxidative stress, IR and inflammation are common to both PCOS and PD, emerging research highlights endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as another shared component.13, 14 Endoplasmic reticulum stress occurs when misfolded proteins accumulate, activating the adaptive unfolded protein response (UPR).15 Initially, the chaperone protein GRP78 (glucose-regulated protein 78) associates with unfolded proteins, thereby promoting the activation of 3 ER-localized transmembrane sensors: PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK); inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1); and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). The unfolded protein response aims to restore ER homeostasis. However, prolonged ER stress can ultimately result in apoptosis through the overexpression of the transcription factor C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP).16

Extensive evidence supports a bidirectional relationship between oxidative stress and ER stress.17 We have previously described increased markers of ER and oxidative stress in leukocytes of women with PCOS, particularly those with metabolic syndrome.14 Endoplasmic reticulum stress has also been observed in granulosa cells in PCOS18, 19, 20 and in periodontal tissues, including human periodontal ligament fibroblasts21 and gingival samples.22

Taken together, these findings indicate a potential link between PCOS, PD and ER stress, although the underlying molecular mechanisms are poorly understood. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine whether gingivitis can modulate ER stress in leukocytes from women with PCOS, as these cells are key indicators of systemic metabolic and inflammatory features.23

Material and methods

Study design

This case–control study was conducted at University Hospital Dr. Peset (Valencia, Spain) between October 2019 and May 2022. The study population included women aged 18–45 years. Specifically, 48 healthy individuals (controls) and 68 patients with PCOS were enrolled. Of these patients, 44 subjects did not have PD (PCOS−), while 24 had gingivitis (PCOS+). The eligibility criteria encompassed female participants aged ≥18 years, recruited either as healthy controls or as patients with PCOS, according to the criteria detailed below. The participants included in the control group were clinically healthy women without a diagnosis of PCOS or other systemic conditions. They were recruited during routine check-ups in the Departments of Endocrinology, Nutrition, and Gynecology of University Hospital Dr. Peset. Patients with PCOS were identified according to the Rotterdam criteria24 and were enrolled during routine appointments in the abovementioned departments. Gingivitis was diagnosed when bleeding on probing (BOP) was ≥10%, according to current periodontal guidelines.25 Participants in the control group were matched with their PCOS counterparts based on the body mass index (BMI) and age, as these parameters have been demonstrated to contribute to both PCOS-related metabolic alterations and periodontal inflammation. In this way, we have taken measure to account for potentially confounding effects.

The exclusion criteria for all participants included the presence of systemic diseases or conditions that could affect periodontal health, such as diabetes or autoimmune disorders, the use of medications known to influence periodontal or hormonal status, pregnancy or lactation, and a history of periodontal treatment within the previous 6 months. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Dr. Peset (study protocol ref. No. 95/19). All participants who met the eligibility criteria completed the study, resulting in no recorded dropouts.

Clinical examination

The patients completed a health questionnaire, including items adapted from the World Health Organization (WHO) Oral Health Questionnaire for Adults.26 Information regarding medication use, medical conditions, alcohol and tobacco habits, and oral hygiene practices (teeth brushing frequency, use of interdental hygiene aids, and time since the last dental visit) was recorded. In addition, blood pressure and anthropometric data were noted. A peripheral venous blood sample was collected after 12 h of fasting, during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle or bleeding deprivation. The biochemical parameters and reproductive hormone profiles were determined during the hospital’s clinical analysis according to the standardized protocols.

A single clinician (CFMA) performed a full periodontal exam in accordance with the consensus criteria.25 Using a periodontal chart, all teeth were probed at 6 sites per tooth (right permanent maxillary first molar, right permanent central incisor, left permanent first premolar, left permanent mandibular first molar, right permanent mandibular central incisor, and right permanent mandibular first premolar) with a Williams-type millimeter probe. Bleeding on probing, clinical attachment level (CAL), probing pocket depth (PPD), and plaque index (using the Silness and Löe index) were assessed.27 The plaque index was determined by measuring the Ramfjord index teeth.28

Flow cytometry

After erythrocyte lysis using a red blood cell lysis buffer (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), a 200-μL blood sample was incubated with 5 μL of APC-CD45 antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA). Total superoxide production was assessed using 1-mM dihydroethidium (dHE) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Fluorescence signals were measured using a flow cytometer (BD Accuri™ C6 Plus Flow Cytometer; BD Biosciences), and 10,000 events were recorded and analyzed for each experiment.

Isolation of PBMCs and protein expression analysis

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using the MACSprep™ leukocyte isolation kit (Milteny Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were lysed in a radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (all products were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of protein (25 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The target proteins were detected by incubating the membranes with primary antibodies against ATF6, GRP78, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha subunit (p-eIF2α), CHOP, IRE1α, glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1), and actin. This was followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies (Supplementary File 2 (available on request from the corresponding author)). The detection of chemiluminescent signals was accomplished through the use of ECL Plus™ reagent (GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA). Signal visualization and densitometric analysis were performed using the Fusion FX5 Acquisition System and Bio1D software, v. 15.03a (Vilbert Lourmat, Marne-la-Vallée, France).

Statistical analysis

The present study was designed to achieve a power of 80% and an α risk of 0.05 to detect 30-unit differences in protein expression by western blot, assuming a standard deviation of 30 units. A minimum of 16 subjects per group were considered (control vs. PCOS and PCOS− vs. PCOS+). The assessment of normality was conducted through the use of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test or the Shapiro–Wilk test. Parametric and non-parametric data was analyzed using the two-sample Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. Oral hygiene variables were evaluated as categorical data using the Kruskal–Wallis test or the Pearson’s χ2 test. To identify factors associated with gingivitis, multivariable linear regression analyses were performed for continuous dependent variables and binary logistic regression analyses for binary outcomes. The evaluation of correlations was conducted by employing Pearson’s or Spearman’s coefficients. The differences were considered significant at p < 0.05, with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism software, v. 9.0.2 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA) and the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

Results

A total of 48 healthy control females and 68 women with PCOS were recruited for the study, including 44 subjects without PD (PCOS−) and 24 individuals with gingivitis (PCOS+). No significant differences were observed in anthropometric or biochemical parameters between the PCOS− and PCOS+ groups, as reported by Márquez-Arrico et al.29 Compared to controls, women with PCOS showed higher waist circumference, as well as increased levels of insulin, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc), and triglycerides, while glucose and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc) levels remained similar (Table 1). Elevated levels of inflammatory indicators, such as high sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP), complement component c3 (C3c) and retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), as well as alterations in reproductive hormones were consistent with the pathophysiology of PCOS. Oral contraceptives and metformin had been prescribed to many of the PCOS patients as part of their routine treatment.

The study population had generally good oral hygiene habits (Table 2), with over 80% of participants in both the control and PCOS groups reporting brushing their teeth at least twice per day, with no statistically significant differences observed between the groups. Similarly, there were no significant differences in the use of interdental hygiene products, such as dental floss and interdental brushes, or mouthwash. The data on the frequency of dental visits and previous periodontal treatment was also collected, showing no differences between the groups.

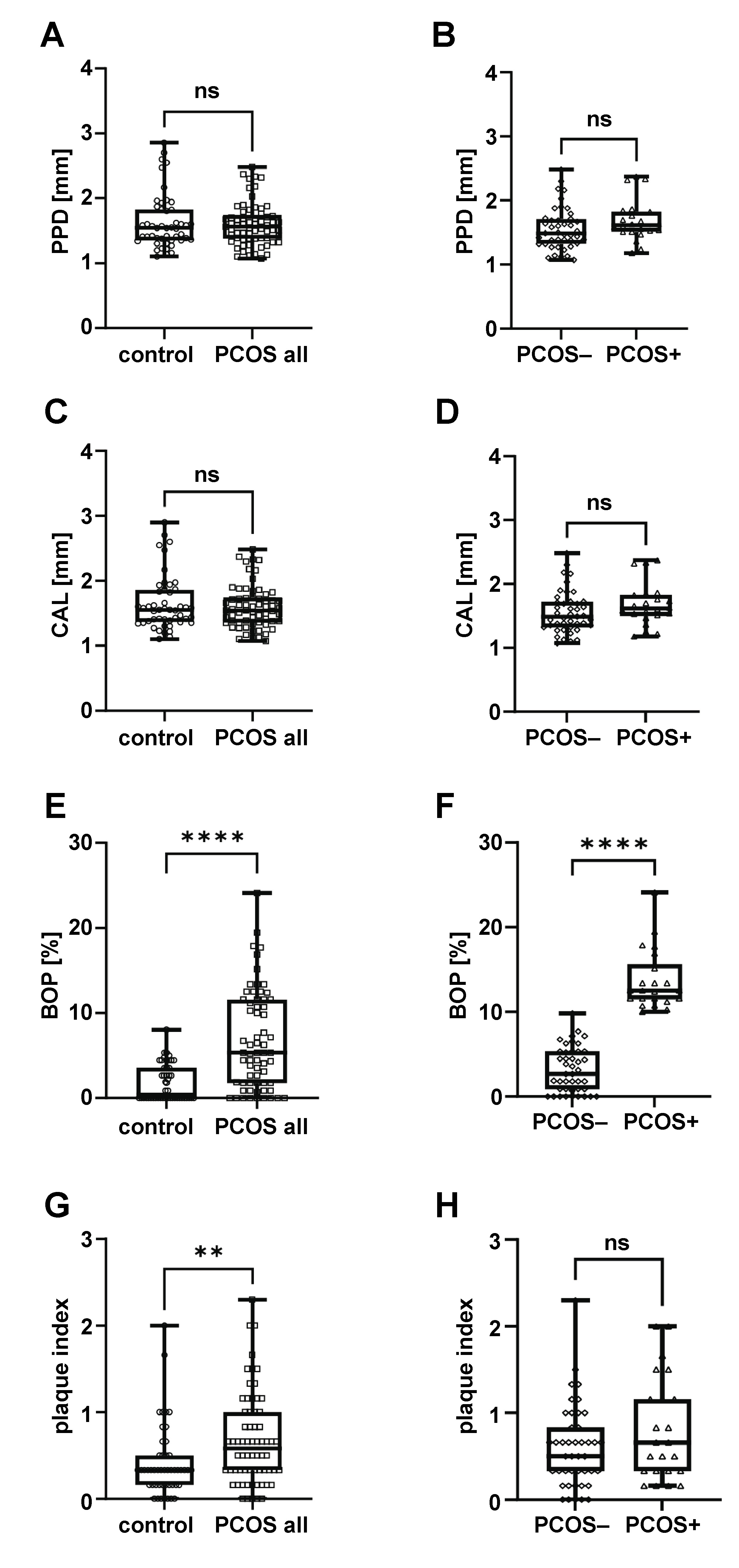

Regarding periodontal parameters, no significant differences in PPD or CAL were detected between the control and PCOS groups (Figure 1A–D). Bleeding on probing was significantly higher in the whole PCOS group compared to controls (Figure 1E). However, no significant differences in BOP were observed between the control group and the PCOS− subgroup (1.935 ±2.336 vs. 3.211 ±2.644, respectively; p > 0.05), suggesting that the increased BOP in the overall PCOS group was driven primarily by the presence of gingivitis (PCOS+, Figure 1F). All participants exhibited very low levels of plaque, with average plaque index scores under 1, below the threshold commonly associated with clinical gingivitis in the general population. However, the plaque index was significantly higher in the PCOS group (Figure 1G), even though oral hygiene practices were similar to those of controls (Table 2). Moreover, within the PCOS group, the plaque index did not differ according to gingivitis status (Figure 1H), suggesting that the increased plaque accumulation was a result of the PCOS pathology itself rather than oral hygiene practices.

In order to determine the factors independently associated with gingivitis, 2 binary logistic regression models were constructed using the enter method (Table 3). Model 1 demonstrated that both PCOS status and poor oral hygiene were independently associated with the presence of gingivitis. Specifically, participants diagnosed with PCOS had a significantly higher risk of gingivitis in comparison to the control group (p < 0.001). Moreover, the practice of brushing once per day or less was associated with an increased risk (p = 0.008). In model 2, which assessed the influence of pharmacological treatments, only PCOS status was significantly associated with gingivitis (p = 0.001). Neither metformin use nor the use of oral contraceptives showed a significant association with gingival inflammation (p > 0.05). These findings support the role of PCOS as an independent risk factor for gingival inflammation, even after taking into account oral hygiene habits and medication use.

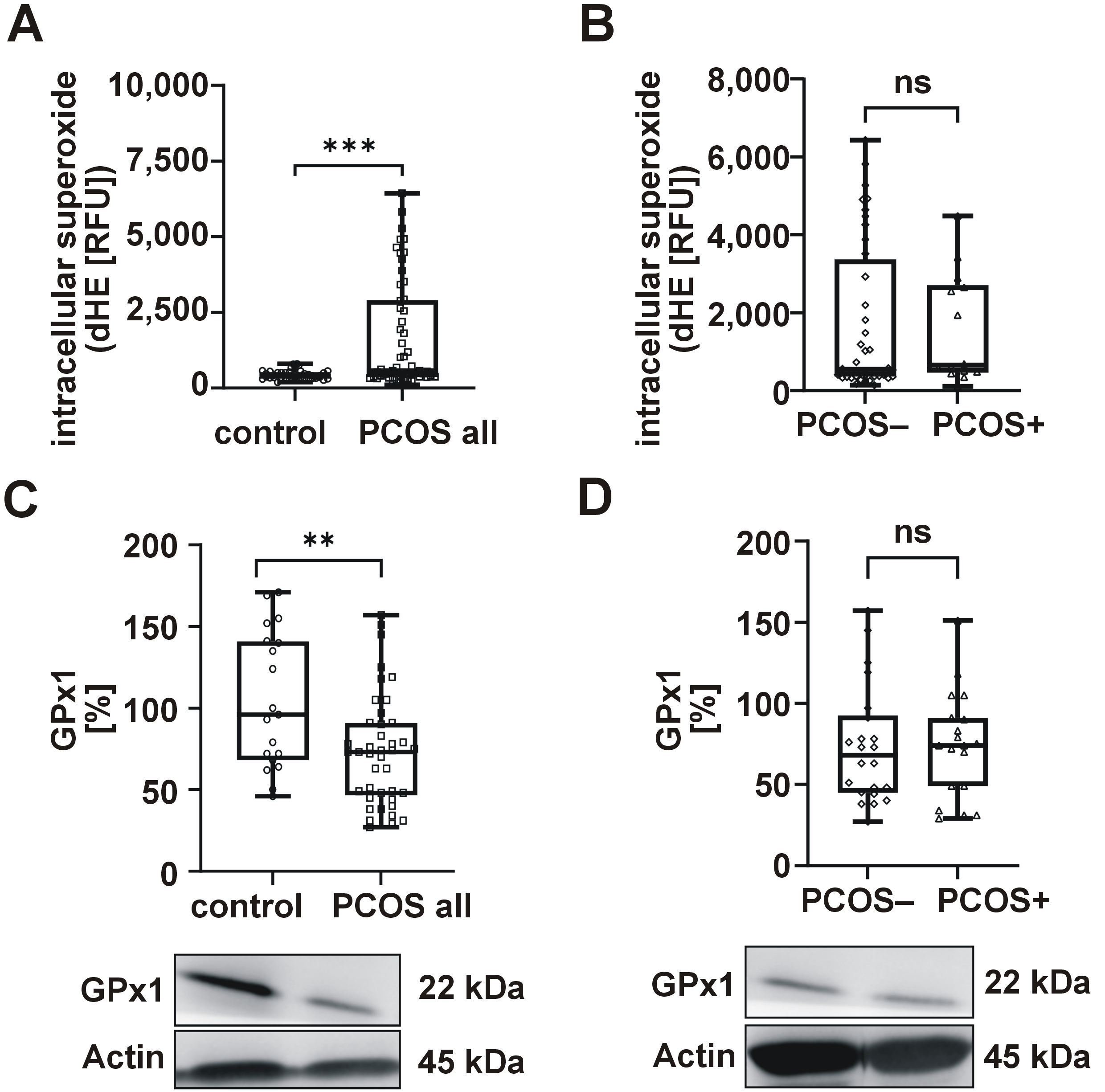

Considering the biological correlation between ER stress, oxidative stress, and both PCOS and PD, we proceeded to analyze relevant molecular markers. The results revealed elevated levels of superoxide (Figure 2A) and reduced GPx1 expression (Figure 2C) in women diagnosed with PCOS, with no observed differences between the PCOS− and PCOS+ groups (Figure 2B,D).

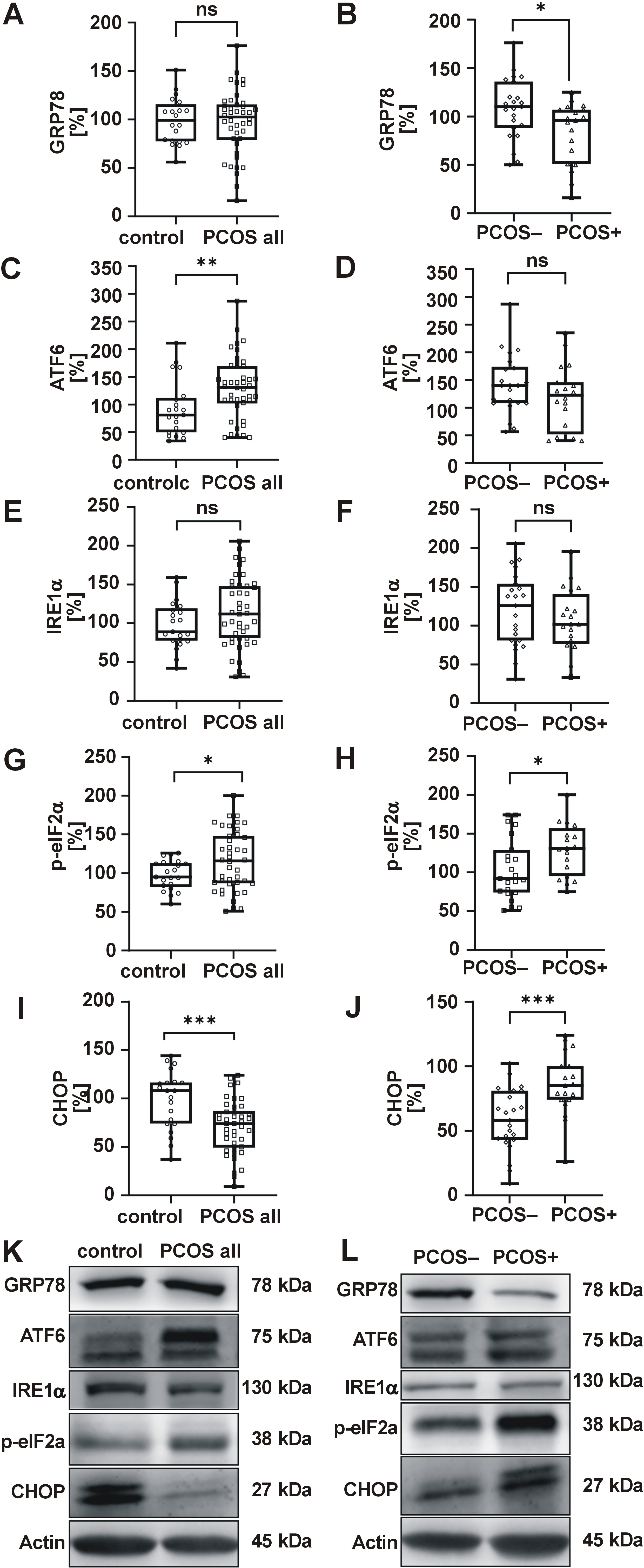

The UPR-related proteins exhibited elevated levels of ATF6 and p-eIF2α in PCOS (Figure 3C,G), with no changes observed in GRP78 or IRE1α (Figure 3A,E), indicating selective activation of the UPR pathways. To assess the activation of UPR downstream proapoptotic pathways, CHOP levels were measured, which were reduced overall in women with PCOS (Figure 3I). However, when the periodontal status was considered, levels of p-eIF2α and CHOP were higher (Figure 3H,J), and GRP78 decreased (Figure 3B) in women with both PCOS and gingivitis, suggesting proapoptotic PERK pathway activation. A sub-analysis, with adjustments made for medication (metformin, oral contraceptives), revealed no significant impact on ER stress markers when comparing the control group with the PCOS group, or the PCOS− group with the PCOS+ group.

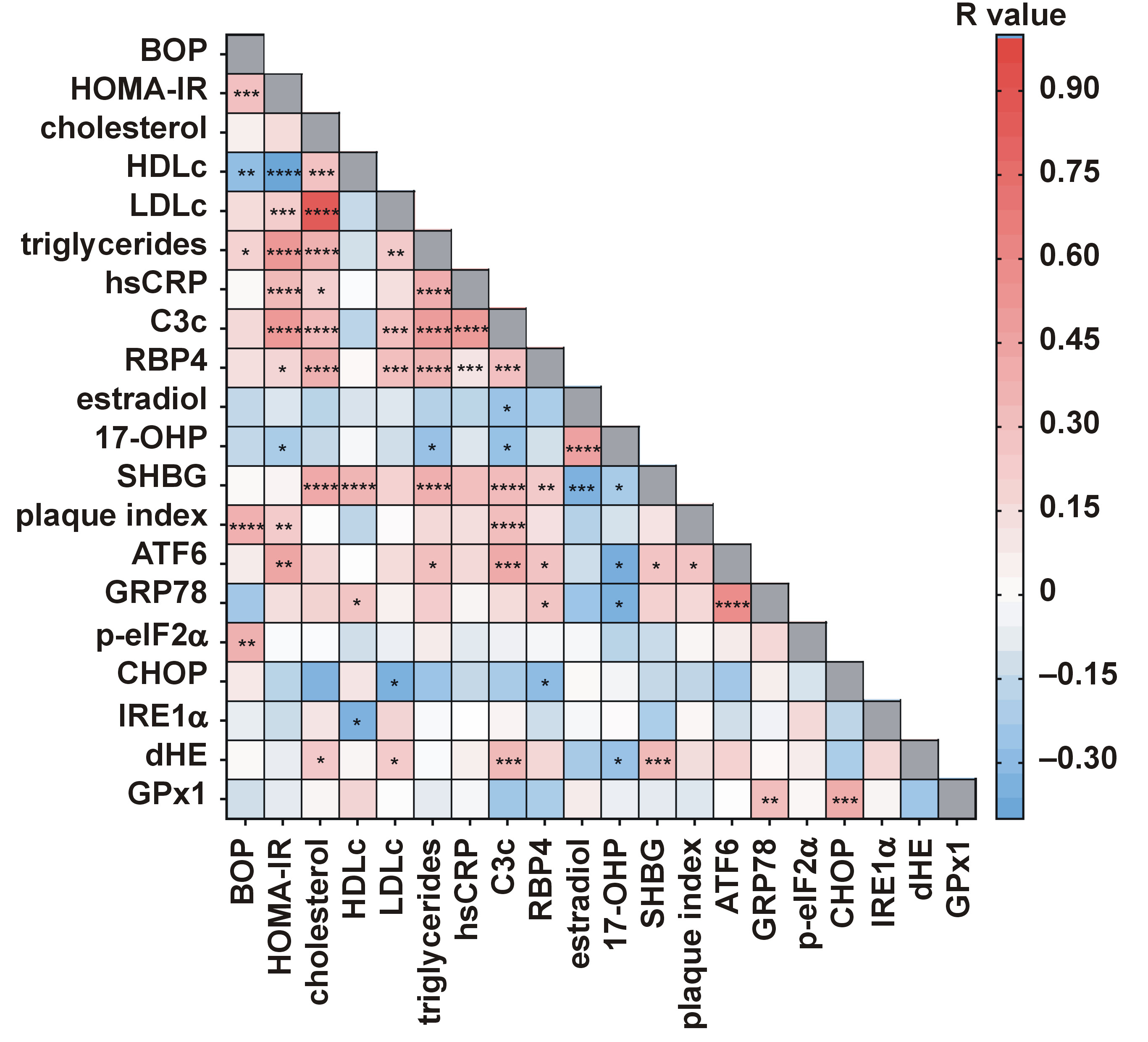

The correlation analysis revealed that BOP was positively correlated with triglycerides (r = 0.215, p < 0.05), HOMA-IR (r = 0.314, p < 0.001) and plaque index (r = 0.393, p < 0.0001), and negatively with HDLc (r = −0.261, p < 0.01) (Figure 4). Additionally, BOP was correlated with p-eIF2α (r = 0.389, p < 0.01), and plaque index was associated with ATF6 (r = 0.293, p < 0.05), suggesting a link between PD and ER stress in PCOS. The multivariable analysis identified p-eIF2α (β = 0.335), triglycerides (β = 0.260) and plaque index (β = 0.254) as independent predictors of BOP, explaining 25.7% of its variance (Table 4).

Discussion

The present findings confirm the presence of oxidative stress and UPR activation via the ATF6 branch in circulating leukocytes of women with PCOS, and offer novel insights into the interplay between PD and metabolic conditions. Gingivitis modulates the UPR by promoting the activation of CHOP and eIF2α, fostering a pro-apoptotic environment that is independently associated with BOP. In contrast, the absence of gingivitis favors a cytoprotective response that is mediated by elevated chaperone GRP78 levels.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is characterized by metabolic disturbances, including altered glucose/lipid metabolism, hormonal imbalance, oxidative stress, and inflammation.2, 3, 4 In this study, we report elevated insulin, HOMA-IR, LDLc, triglycerides, and altered sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), estradiol and 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) levels, all consistent with the pathophysiology of PCOS.

Oral health is increasingly recognized as an essential component of women’s general health, with implications for various reproductive stages.30 In this sense, emerging evidence links PCOS to a higher prevalence of PD.6, 31 Although dental plaque is the main etiological factor for gingivitis, the results of this study support the interpretation that PCOS is an independent risk factor for periodontal inflammation. In the multivariable analyses, PCOS status was consistently associated with a higher risk of gingival inflammation, even after adjusting for oral hygiene habits and medication. Despite plaque levels being similar across the groups, women with PCOS exhibited greater gingival inflammation, indicating a heightened inflammatory response that cannot be attributed to local factors or medication effects. This interpretation aligns with previous evidence suggesting that PCOS can exacerbate periodontal inflammation independently of plaque levels, likely through systemic mechanisms involving oxidative stress and immune dysregulation.29

In order to further explore potential shared mechanisms underlying PCOS and PD, an assessment of markers of oxidative stress and ER stress was conducted. Oxidative stress has been identified as a key factor in the systemic impact of PD and comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome and diabetes.32, 33 Indeed, the interplay between oxidative stress and inflammation is a central pathogenic mechanism across a broad spectrum of diseases ranging from diabetic nephropathy34 to skin cancer.35 Thus, it can be hypothesized that any interaction between PD and PCOS is influenced by oxidative stress. Only 3 studies have analyzed systemic oxidative stress in women diagnosed with both PCOS and PD. Saglam et al. reported impaired redox status in serum and saliva, as indicated by elevated levels of 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine and malondialdehyde, and reduced total antioxidant capacity in subjects with PCOS and periodontitis.36 Dursun et al. observed elevated myeloperoxidase and nitric oxide levels in gingival crevicular fluid.5 Our group reported high myeloperoxidase levels and reduced glutathione levels in women with PCOS, with no gingivitis-related differences.29

In the present study, we have evaluated intracellular oxidative stress in PBMCs, which serve as systemic sensors of metabolic disease,37 and have found increased intracellular superoxide production and reduced GPx1 levels in women with PCOS, both of which are consistent with serum markers of oxidative stress. However, no differences emerged when gingivitis was considered, possibly due to its early, reversible nature. In fact, prior research has demonstrated that severe periodontitis is associated with increased intracellular superoxide levels, though no differences were observed in mild or moderate cases.38

Oxidative stress and ER stress are closely interconnected; the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) intensifies protein misfolding in the ER, further exacerbating oxidative damage and triggering inflammatory responses.39 Our findings demonstrated elevated levels of ATF6 and p-eIF2α in PBMCs of women with PCOS. Moreover, the correlation between superoxide and hyperlipidemia, as well as elevated C3c and SHBG levels, was identified. Concurrently, the association between diminished GPx1 and GRP78 and CHOP downregulation was determined. These findings suggest that redox imbalance in PCOS may induce UPR activation. Our data align with reports of ER stress activation in granulosa and cumulus cells of women with PCOS.18, 40, 41

Endoplasmic reticulum stress has also been observed in PD models.21, 22, 42 For instance, periodontal ligament stem cells from patients with periodontitis exhibited elevated UPR markers.43 Moreover, increased UPR gene expression was noted in periodontal ligament fibroblasts exposed to lipopolysaccharide.21 However, no previous study has evaluated ER stress in leukocytes of women with both PCOS and gingivitis. In the current study, we observed the activation of pro-apoptotic mechanisms triggered by ER stress through PERK pathway activation, as increased p-eIF2α levels induce ATF4 translation, thereby promoting CHOP expression.16, 44 Previous studies have reported the upregulation of apoptosis via the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP signal pathway in human periodontal ligament cells derived from patients with periodontitis.45 Accordingly, our findings suggest that the upregulation of CHOP and p-eIF2α may contribute to a pro-apoptotic profile in the PBMCs of women with PCOS and gingivitis. Conversely, an augmented GRP78 pro-survival signal in the absence of gingivitis may indicate a compensatory mechanism.46 Interestingly, both clinical indicators of gingivitis, namely BOP and plaque index, were positively associated with p-eIF2α and ATF6, respectively. In contrast, GRP78, ATF6 and CHOP were correlated with systemic clinical parameters. These findings suggest that UPR activation in women with PCOS is primarily driven by underlying metabolic dysfunction and hormonal imbalance, and further exacerbated by the presence of PD.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine systemic UPR activation in the context of gingivitis, a condition that remains largely understudied. Given the limited literature on the topic, we referenced studies on more advanced stages of PD to guide the interpretation of the results. Nonetheless, our conclusions are strengthened by the high methodological rigor of the study, including comprehensive periodontal assessments by an experienced dentist, the use of validated oral health questionnaires, and robust statistical analyses accounting for key confounders.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the number of patients with gingivitis was relatively small, despite a prior sample size calculation, and the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Second, the hospital-based setting may introduce some selection bias; however, all diagnoses were made in a tertiary care following rigorous clinical and diagnostic standards to ensure consistency and reliability. Additionally, although PCOS phenotypes may differ in their metabolic and inflammatory profiles, we did not stratify participants by phenotype because of limited access to standardized clinical assessments and reliance on routine androgen assays. The sample size further restricted statistical power for subgroup analyses. Collectively, these limitations highlight the need for future studies with larger cohorts and detailed phenotyping.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings elucidate the role of gingivitis in aggravating metabolic dysfunction in women with PCOS and highlight shared ER/oxidative stress pathways. These insights underscore the importance of early periodontal care in the management of metabolic disorders and encourage future interdisciplinary research to further clarify the underlying biological mechanisms.

Trial registration

This observational study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration No. NCT06184412; https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06184412).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Dr. Peset, Valencia, Spain (study protocol ref. No. 95/19).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, USA) has been employed to enhance the language and modify the text’s length.