Abstract

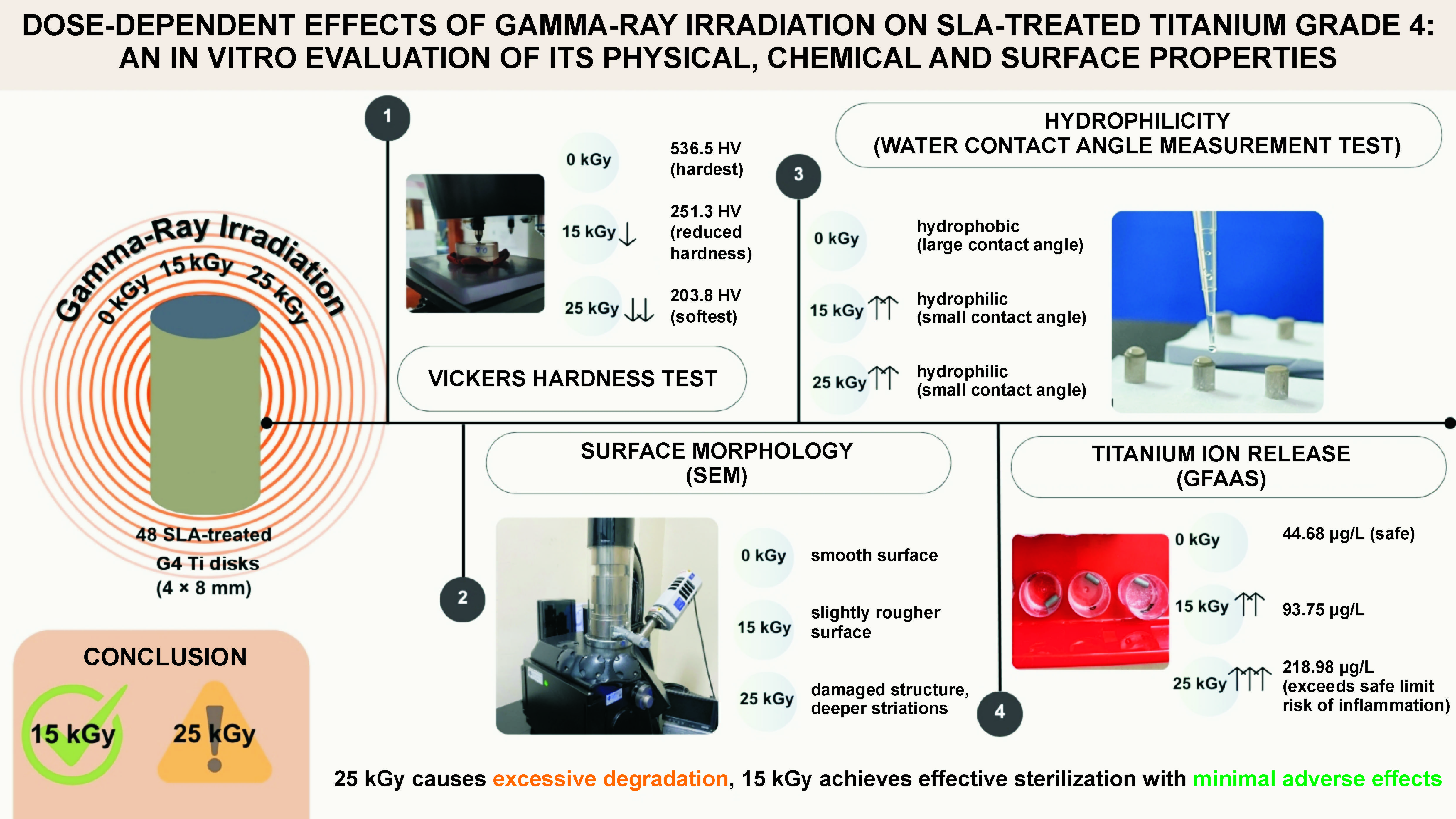

Background. Gamma-ray sterilization is commonly used for dental implants, but may alter their physical, chemical and surface properties.

Objectives. The present study compared gamma-ray irradiation doses of 15 kGy and 25 kGy in terms of their effects on the physical (microhardness), chemical (titanium (Ti) ion release) and surface (morphology and hydrophilicity) properties of sand-blasted, large-grit, acid-etched (SLA) Ti Grade 4 (G4) implants.

Material and methods. A total of 48 cylindrical Ti G4 samples (4 mm in diameter, 8 mm in thickness) were irradiated using cobalt-60 (Co-60) gamma radiation at 0 kGy (non-irradiated), 15 kGy or 25 kGy doses. Post-irradiation analyses included testing Vickers hardness (HV), Ti ion release in simulated body fluid (SBF) after 2 weeks, the water contact angle (θ), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for morphology assessment. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results. Gamma-ray irradiation significantly impacted all measured properties. The mean hardness decreased from 536.5 HV (non-irradiated) to 251.3 HV (15 kGy) and 203.8 HV (25 kGy) (p < 0.001); no significant difference was observed between 15 kGy and 25 kGy. Titanium ion release increased with a radiation dose: 44.68 μg/L (non-irradiated); 93.75 μg/L (15 kGy; p = 0.0292 vs. control); and 218.98 μg/L (25 kGy; p < 0.001 vs. control and 15 kGy). The water contact angles approached 0° post-irradiation, indicating a shift to superhydrophilicity, significantly different from the moderately hydrophilic control (p = 0.0085), with no difference between the radiation doses (p = 0.1266). The SEM analysis revealed more pronounced micro-damage and roughness at 25 kGy.

Conclusions. Both 15 kGy and 25 kGy significantly altered surface properties, but 25 kGy induced greater Ti ion release and micro-damage. Within the study limitations, 15 kGy is recommended as the preferred sterilization dose, as it maintains sterility while minimizing mechanical degradation and excessive Ti ion release as compared to 25 kGy.

Keywords: gamma radiation, sterilization, titanium implant

Introduction

Dental implant fixtures must be completely sterile before clinical use to prevent peri-implant infections that jeopardize osseointegration. Biomaterial guidelines emphasize that sterilization methods should eliminate pathogens without degrading the properties of the implant. Various sterilization techniques include steam autoclaving, chemical disinfectants and radiation (gamma or electron-beam).1 Among these, gamma-ray irradiation is widely used due to its deep penetration, decisive microbial lethality, and ability to sterilize without thermal damage or chemical residues.2, 3, 4 Using high-energy photons (usually from a cobalt-60 (Co-60) source), gamma-ray irradiation effectively inactivates bacteria, viruses and spores by inducing irreparable DNA damage, ensuring sterility without leaving toxic byproducts.1, 2 Gamma rays can sterilize devices in their final packaging at ambient temperature, making them suitable for mass production.5 These advantages have led to gamma-ray sterilization becoming an FDA (Food and Drug administration)- and EMA (European Medicines Agency)-approved standard method in the dental implant industry.6

Standard gamma sterilization protocols often employ doses around 25 kGy, as it meets the requirements regarding the sterility assurance level for medical devices.7 However, ensuring that such radiation does not compromise the physical and chemical integrity of titanium (Ti) implants during the terminal sterilization process is critical.7 Studies have shown that exposure to gamma-ray irradiation alters the physical (microhardness), chemical (Ti ion release) and surface (morphology and hydrophilicity) properties of Ti implants.2 Surface roughness and hydrophilicity play a crucial role in osseointegration.8, 9 Implants with moderate roughness (Sa 1–2 μm) and high hydrophilicity exhibit enhanced osseointegration.1 Ueno et al. demonstrated that gamma-ray irradiation enhanced the hydrophilicity of Ti surfaces, reducing the water contact angle (θ) to approx. 10°, which might improve osseointegration.2 Similarly, El-Bediwi et al. reported that gamma-ray exposure increased surface roughness and microstructural changes in Ti, affecting its mechanical integrity.10 Research has shown that gamma-ray irradiation can disrupt the titanium oxide (TiO2) layer, potentially increasing Ti ion release and raising concerns about cytotoxic effects.1, 11 Zhou et al. further report that mechanical wear during implantation and prolonged chemical corrosion may also compromise this oxide layer.11 Despite these findings, the issue of Ti ion release and its clinical implications remain relatively underexplored, particularly in relation to peri-implant conditions and long-term biocompatibility.12, 13

Despite the widespread use of 25 kGy in sterilization protocols, emerging evidence suggests that lower doses, such as 15 kGy, might be sufficient to achieve sterility while minimizing adverse effects on Ti implants.11, 14, 15, 16 Preliminary bioburden testing, which quantifies microbial contamination before sterilization, has shown that a dose of 15 kGy can be substantiated under the International Organization for Standarization (ISO) 11137-2 VDmax 15 protocols as sufficient to achieve microbial reduction to acceptable levels, provided the natural bioburden is very low.17 Moreover, the ISO standards for medical device sterilization recommend dose adjustments based on bioburden assessments, rather than a fixed-dose approach.2 Preliminary research on the prototype Ti implant sterilization using gamma rays identified a bioburden threshold at a 15 kGy dose.6 However, studies that have directly compared the effects of 15 kGy vs. 25 kGy on Ti implant properties are limited.

Therefore, this study aims to analyze the effects of gamma-ray irradiation at 15 kGy and 25 kGy on the mechanical properties (microhardness), surface characteristics (morphology and hydrophilicity) and Ti ion release of SLA (sand-blasted, large-grit, acid-etched)-treated Ti implants. Understanding the impact of different doses on implant integrity is crucial for optimizing sterilization protocols while preserving implant performance.

Material and methods

This quasi-experimental study, conducted from April to July 2023, aimed to investigate the effects of gamma-ray irradiation on cylindrical SLA-treated Ti surfaces. The research sample consisted of 48 cylindrical, non-threaded Ti implants (4 mm in diameter, 8 mm in thickness) made from pure Grade 4 (G4) Ti, manufactured by Pudak Scientific (Bandung, Indonesia). Titanium samples were prepared using a dual microtopography surface treatment called sand-blasted, large-grit, acid-etched (SLA). First, the samples were sand-blasted with alumina particles (200–300 µm). Next, they were immersed in 48% hydrofluoric acid at room temperature for 30–60 s. Subsequently, the samples were immersed in a mixture of 37% hydrochloric acid and 97% sulfuric acid in a 2:1 ratio at temperatures ranging from 80°C to 100°C for 5–6 min, which created a secondary micro-scale topography. Finally, the samples were rinsed thoroughly with distilled water, ultrasonically cleaned, and air-dried before gamma-ray irradiation.

A total of 48 cylindrical SLA-treated Ti samples were used in this study. The samples were divided into 3 irradiation groups depending on the dose used (0 kGy, 15 kGy and 25 kGy), with 16 samples per group. Within each group, the samples were allocated to 4 assessment categories: physical properties (Vickers hardness); surface morphology (scanning electron microscopy (SEM)); hydrophilicity (the contact angle); and Ti ion release (graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (GFAAS)). Each assessment was performed on the samples from all 3 irradiation groups to enable consistent comparisons across doses. The Ti surface was the independent variable, while the dependent variables included physical characteristics, ion release, morphology, and hydrophilicity. Gamma-ray dose levels (0 kGy, 15 kGy and 25 kGy) were controlled to maintain uniformity.

Gamma-ray irradiation was performed using a Co-60 radioisotope device (Gammacell 220; Nordion Inc., Ottawa, Canada), which emits electromagnetic radiation onto Ti samples packed in polyethylene (PE) plastic. The samples were exposed to irradiation doses of 15 kGy and 25 kGy. The physical analysis was conducted at the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), the morphological and ion release analyses at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), and hydrophilicity testing at the Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia.

Assessment methods

Physical properties

Hardness was measured with a Vickers hardness tester (HV-10; Mitutoyo, Kawasaki, Japan), which uses a diamond pyramid-shaped indenter (136°) that is pressed into the surface of the test material (Ti) under a controlled load. The test was conducted on the irradiated (15 kGy and 25 kGy) and non-irradiated samples. Hardness was expressed in Vickers hardness units (HV).

Morphology

Surface morphology was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (JSM-IT300; JEOL USA Inc., Peabody, USA), with a resolution of 0.1–0.2 nm. Observations were conducted at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV with a working distance of 10 mm, using the secondary electron imaging (SEI) mode. The samples were analyzed at magnifications of ×150, ×500, ×1,000, ×2,500, ×5,000, and ×10,000.

Hydrophilicity

The contact angle (θ) of a 5-microliter water droplet on the Ti surface (non-irradiated, and irradiated at 15 kGy and 25 kGy) was measured using the ImageJ contact angle measurement device (https://imagej.net/ij). The contact angle was calculated using the convexity formula θ = 2α. The water contact angle classification was as follows: superhydrophilic (θ ≈ 0°); hydrophilic (0° < θ < 90°); hydrophobic (90° < θ < 120°); ultrahydrophobic (120° < θ < 150°); and superhydrophobic (θ > 150°).

Chemical properties

Titanium ion release was measured after 2 weeks of immersion in simulated body fluid (SBF), using GFAAS (AAnalyst 800; PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA), with results expressed in µg/L.

Materials and equipment

The materials used in this study include cylindrical Ti G4 samples and the SBF solution. The equipment comprised six 250-milliliter glass jars, 3 dropper pipettes, tweezers, label paper, gloves, masks, a Vickers hardness tester, a SEM, a contact angle measurement system (Image J), a GFAAS device, and an incubator.

Procedure and data collection

Titanium sample grouping

The Ti samples were divided into 3 groups: group 1 served as the control group (non-irradiated samples); group 2 included samples irradiated at a 15 kGy gamma-ray dose; and group 3 consisted of samples exposed to a 25 kGy gamma-ray dose.

Gamma-ray irradiation

The Ti samples underwent gamma-ray irradiation at doses of 15 kGy and 25 kGy, while the control group remained non-irradiated at 0 kGy, which ensured a comparative analysis of the effects of gamma-ray exposure on the Ti surface.

Vickers hardness tests

The gamma-irradiated (15 kGy, 25 kGy) and non-irradiated samples were mounted onto specimen holders. A Vickers hardness tester was then used – a 50-gram load was applied to the central top surface of the Ti cylinders for 10 s to measure their hardness.

Morphology analysis using SEM

The Ti samples from all groups were affixed to specimen holders for the surface morphology analysis. The surface structure was examined using a SEM at ×150, ×500, ×1,000, ×2,500, ×5,000, and ×10,000 magnifications, enabling a detailed observation of morphological changes.

Hydrophilicity testing

The water contact angle measurements for the 0 kGy, 15 kGy and 25 kGy samples were categorized as superhydrophilic at 0°, hydrophilic for angles between 0° and 90°, hydrophobic within the 90–120° range, ultrahydrophobic between 120° and 150°, and superhydrophobic when exceeding 150°. A scoring system was used to quantify these properties, with a score of 1 assigned for superhydrophilic (0°), 2 for hydrophilic (<90°), 3 for hydrophobic (90–120°), 4 for ultrahydrophobic (120–150°), and 5 for superhydrophobic (>150°). A 5-microliter water droplet was applied to the surface of each Ti sample using a micropipette. The contact angle between the droplet and the Ti surface was measured using a contact angle measurement device to determine the hydrophilicity properties of each sample.

Ion release testing

The Ti samples from all groups were immersed in SBF inside small plastic containers. The containers were incubated at 37°C for 2 weeks, with the SBF solution replaced every 2 days to simulate in vivo conditions. After 2 weeks of immersion, the collected SBF solution was analyzed for Ti ion release, using GFAAS.

Data analysis design

Data analysis involved a mixed-method approach, integrating quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative data was analyzed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc pairwise tests for hardness and ion release, while the Kruskal–Wallis and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests were applied for hydrophilicity (Table 1). Statistical test selection was based explicitly on data distribution and variance characteristics, assessed via the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality and Levene’s test for the homogeneity of variance. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Effect sizes (e.g., partial eta-squared (ηp2) for ANOVA, Cohen’s d) were also calculated to interpret the magnitude of differences between the groups. Qualitative analysis involved the descriptive evaluation of the morphological characteristics observed through SEM imaging, where surface features such as striations, micro-cracks and roughness variations were compared across the experimental groups.

The sample size was determined using Federer’s formula, chosen for its practical suitability in exploratory laboratory conditions with limited resources and unknown prior variance estimates. Multiple identical samples per group provided internal replication, ensuring robust statistical comparisons. To minimize confounding variables, environmental conditions, sample purity and preparation consistency were strictly controlled, including uniform temperature and humidity monitoring, consistent batch sourcing of Ti G4, and rigorous standardization of SLA treatment.

Results

Vickers hardness tests

The mean Vickers hardness values decreased substantially with gamma-ray irradiation. The non-irradiated control group showed the highest hardness (536.5 ±5.3 HV), whereas the values for the 15 kGy and 25 kGy groups were markedly lower at 251.3 ±8.1 HV and 203.8 ±63.2 HV, respectively. The one-way ANOVA confirmed a highly significant overall difference among the 3 groups (p < 0.0001; ηp2 ≈ 0.95). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that both 15 kGy and 25 kGy irradiation led to significantly reduced hardness as compared to the control (p < 0.001 for each dose). For example, the drop in hardness at 25 kGy corresponded to a very large effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 7). There was no statistically significant difference between the 15 kGy and 25 kGy groups (p > 0.05), suggesting that most mechanical degradation occurs by 15 kGy (Table 2).

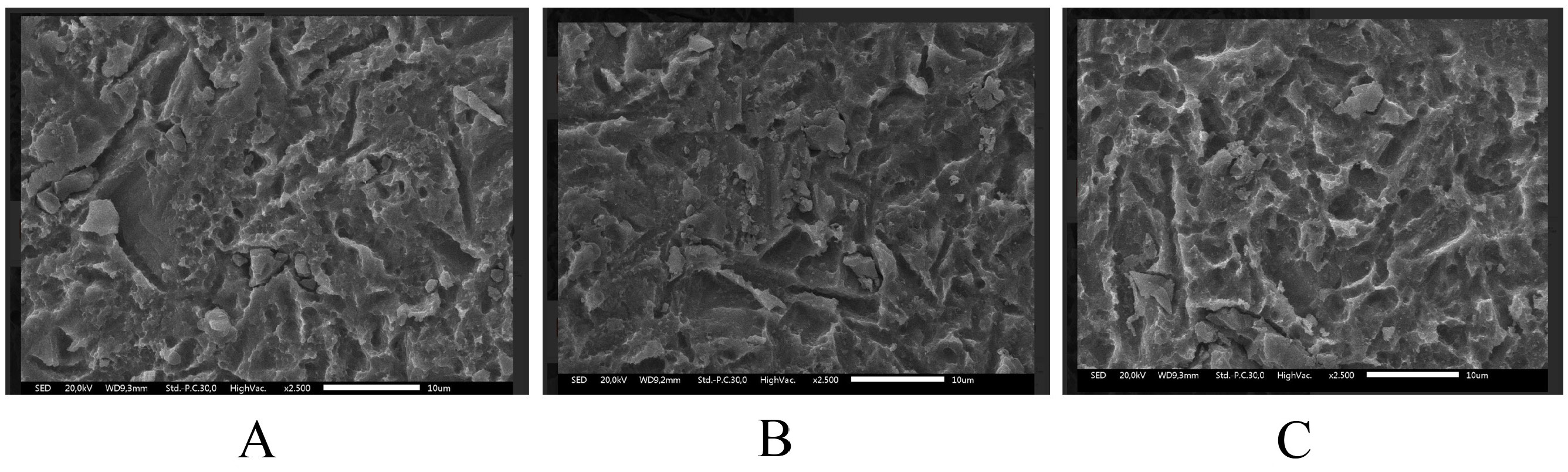

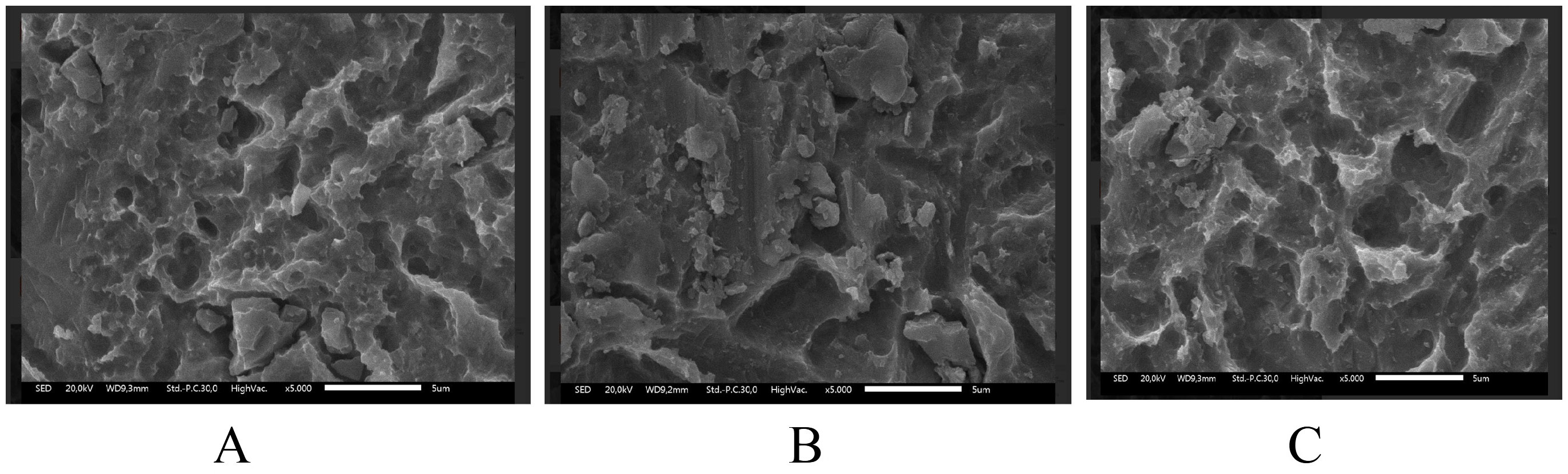

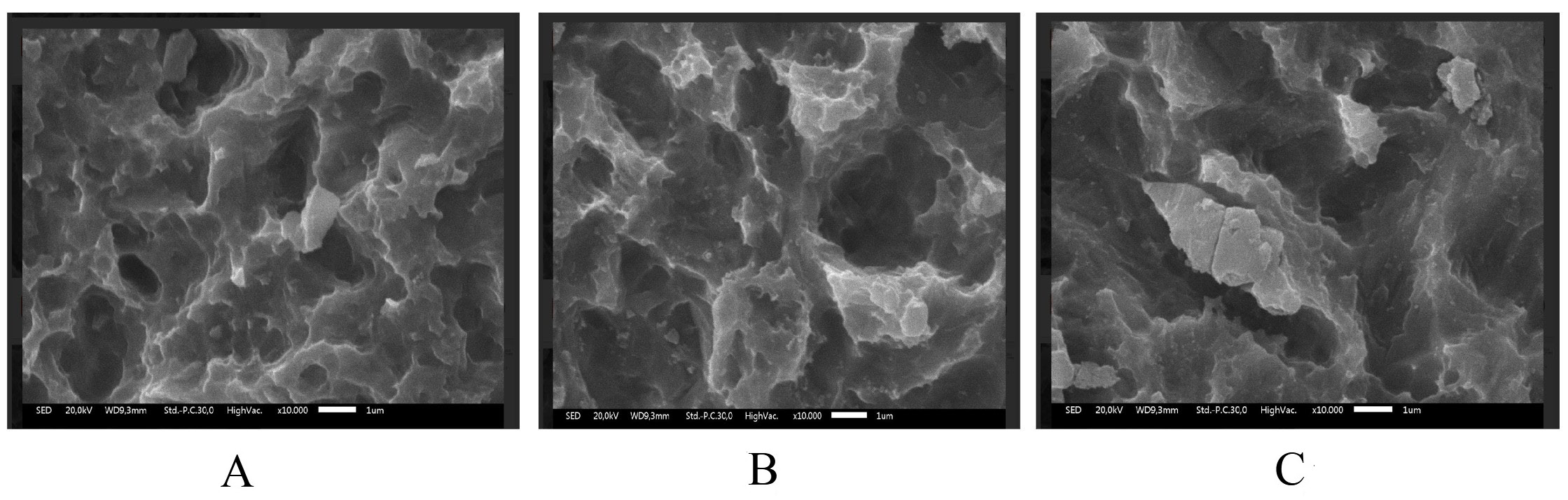

Morphological analysis using SEM

Scanning electron microscopy revealed dose-dependent surface damage on the SLA-treated Ti (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3). The non-irradiated surfaces showed rough micro-texture, characteristic of SLA treatment, while higher radiation doses produced more pronounced microstructural alterations. The 25 kGy samples exhibited deeper striations, pits and micro-cracks than the 15 kGy and control samples. Although quantitative roughness measurements were not performed, SEM imaging demonstrated increased micro-damage and structural irregularities correlating with a radiation dose.

Hydrophilicity testing

Both irradiated groups showed a shift toward superhydrophilicity, with near-zero water contact angles, whereas the control surface remained moderately hydrophilic. The overall Kruskal–Wallis test result shown in Table 3 indicates a statistically significant difference in hydrophilicity among the 3 groups (p = 0.0085). Pairwise comparisons revealed that even the lower dose of 15 kGy significantly improved surface wettability as compared to the control group (p = 0.0082), supporting the meaningful effect of gamma-ray irradiation at this dose. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the 15 kGy and 25 kGy groups (p = 0.1266), suggesting a saturation effect where hydrophilicity reaches its maximum potential beyond 15 kGy.

Ion release testing

The ion release analysis demonstrated a clear dose-dependent response. The one-way ANOVA revealed a highly significant overall difference in Ti ion release among the 3 groups (p < 0.0001) (Table 4). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed significantly higher Ti ion release in the 15 kGy group (93.75 ±16.98 μg/L) than in the control group (44.68 ±2.48 μg/L) (p = 0.0292). Furthermore, the 25 kGy group exhibited significantly higher Ti ion release (218.98 ±43.11 μg/L) than both the control and 15 kGy groups (p < 0.001 for both comparisons), indicating a dose-dependent increase in ion release.

Discussion

Gamma-ray exposure significantly reduced implant hardness, with the highest hardness observed in the non-irradiated control group (536.5 ±5.3 HV), and progressively lower hardness values observed at doses of 15 kGy (251.3 ± 8.1 HV) and 25 kGy (203.8 ±63.2 HV). Titanium G4 dental implants typically require a surface hardness of at least 280 HV to withstand masticatory loads. Although gamma-ray irradiation reduced the measured surface hardness to 251.3 ±8.1 HV at 15 kGy, it is important to note that the depth of hardness deterioration was not assessed in this study. Therefore, while surface weakening is evident, it remains unclear whether the bulk mechanical integrity necessary for masticatory loading is significantly compromised. Further depth-resolved hardness analyses are warranted to confirm the clinical implications. Excessive occlusal stress beyond the tolerance of the bone and the implant can cause micro-fractures, reduce bone density at the implant neck and lead to crater-like defects. Studies show that irradiation at 10 kGy and 20 kGy alters Ti microstructure, affecting the crystal size and atomic bonds. High-energy gamma rays induce surface defects, atomic loss and movement, ultimately leading to Ti weakening.2, 18 Excessive gamma-ray irradiation at 25 kGy caused significant surface destruction, as shown in the SEM analysis (Figure 2). The irradiated samples displayed irregular, rough surfaces, with the most severe damage in the 25 kGy group. Similar studies have shown that higher irradiation doses, such as 30 kGy, create deeper grooves and increase roughness. Optimal implant surface roughness (1–100 µm) enhances cellular activity, osseointegration and bone apposition by facilitating fibrin protein adhesion and osteogenic cell attachment, and improving implant stability within the host bone.19, 20

In this research, all samples were surface-treated using the SLA technique, which made the sample’s surface topography rough or irregular. Gamma-ray irradiation further altered surface characteristics by inducing disruptions in atomic bonding within the TiO2 layer, thereby increasing surface roughness while simultaneously inducing Ti weakness. The SEM morphology results correlate with the physical properties of gamma-irradiated Ti. However, this study did not include quantitative surface roughness measurements; therefore, exact roughness values could not be determined.21, 22, 23

Gamma rays, in addition to their excellent sterilization effects, can also enhance the osseointegration capability of implants. The hydrophilicity of the Ti surface can impact various biological aspects, including facilitating the adhesion of macromolecular proteins to the Ti surface, influencing cell interactions in both hard and soft tissues, and affecting bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation.24, 25 This pronounced shift toward complete wetting reflects radiation-induced alterations in the surface chemistry, such as removing hydrophobic contaminants and creating hydroxyl groups on the oxide layer. These changes enhance the ability of the surface to attract and bind water molecules, contributing to improved protein adsorption and subsequent cell attachment, which are crucial for successful osseointegration.

After the deposition of blood proteins on a hydrophilic implant surface, successful integration between the implant and the bone requires precursor osteoblast cells, followed by differentiation, extracellular matrix synthesis and soft tissue growth. A hydrophilic surface facilitates the invasion of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), promoting osteoblast maturation at the implantation site. Alongside hard tissue formation, the growth of soft tissue, such as the connective tissue layer beneath stratified squamous epithelial cells, is essential for covering the implantation site, and protecting against infection and peri-implantitis.26, 27 Gittens et al. reported that keratinocyte proliferation on superhydrophilic surfaces improved epithelial closure.28

Another biological effect of surface hydrophilicity is its influence on bacterial colonization. Hydrophilic bacterial strains tend to adhere more easily to other hydrophilic surfaces; the same applies to hydrophobic bacteria. Bacteria on hydrophilic surfaces can contribute to plaque formation, a key factor in peri-implantitis. Therefore, surface treatment that inhibits biofilm maturation, such as polyethylene coating, may be beneficial.28, 29

The findings of this study demonstrate that increased gamma-ray exposure resulted in a surface property shift from hydrophobic to hydrophilic, particularly in the 15 kGy and 25 kGy groups. When metals like Ti are irradiated with gamma rays, their surface properties change to hydrophilic due to a phenomenon known as radiation-induced surface activation (RISA).30, 31 The working principle of RISA involves excitation and altered spacing between oxide particles, leading to atomic separation within the Ti-O-Ti bonds. Consequently, oxygen atoms (O2) attract water molecules from the air, further enhancing surface hydrophilicity.

Ueno et al. described another mechanism contributing to hydrophilicity enhancement – organic molecules on the Ti implant surface being effectively decomposed by gamma-ray irradiation.2 This process results in a clean Ti surface, facilitating the binding of oxygen atoms from the surrounding air, further promoting the hydrophilic transformation of the implant surface.2, 32, 33 Gamma rays alter the hydrophilicity of the implant surface and disrupt the TiO2 bonds, leading to ion release.34 In the present study, ion release increased significantly with higher gamma-ray doses, with the highest ion concentration observed in the 25 kGy group (218.98 ±43.11 µg/L), followed by the 15 kGy group (93.75 ±16.98 µg/L), and the lowest in the non-irradiated group (44.68 ±2.48 µg/L). Notably, ion release in the 25 kGy group slightly exceeded the safe threshold for human exposure (214.28 µg/L). Excessive Ti ion release can provoke systemic responses, including inflammatory reactions mediated by interleukin (IL)-1β activation and macrophage recruitment, potentially leading to peri-implant bone resorption (peri-implantitis).

Elevated ionic dissolution might influence peri-implant tissues or raise biocompatibility concerns over time, although the absolute levels observed here are still relatively low. Notably, a 15 kGy dose approx. doubled ion release relative to the non-irradiated control. In contrast, a 25 kGy dose quintupled it, highlighting the disproportionate impact of higher gamma radiation doses on Ti dissolution. This emphasizes the importance of carefully selecting sterilization parameters to ensure long-term implant stability.35, 36, 37 Clinically, minimizing ion release is critical to preventing potential inflammatory or cytotoxic effects. Therefore, a gamma-ray sterilization dose of 15 kGy is recommended for Ti implants, as it effectively sterilizes while maintaining Ti ion release within safe human exposure limits.38, 39 According to the ISO 11137 standard, the determination of gamma-ray sterilization doses (15 kGy or 25 kGy) should be based on bioburden assessment. This study found that 15 kGy and 25 kGy doses showed no significant differences, except in ion release properties. A 15 kGy dose was identified as optimal, effectively sterilizing the implant material without significantly compromising its hardness, morphology or hydrophilicity. However, this study was limited by the absence of quantitative surface roughness measurements, pointing to the need for further in vitro research on Ti bioactivity and osseointegration after gamma-ray irradiation.40, 41

Several limitations of this in vitro evaluation should be acknowledged. Aside from the lack of quantitative roughness data mentioned above, the study was conducted on smooth cylindrical specimens in a controlled laboratory setting, which might not capture all aspects of clinical implant performance. In vivo conditions (such as bone remodeling dynamics and long-term body fluid exposure) could modulate the observed effects. Additionally, our focus was on short-term outcomes (immediate post-irradiation properties and ion release at 2 weeks), so the long-term effects of gamma-ray irradiation on implant surfaces remain uncertain. Despite these limitations, the consistently large effect sizes and clear trends observed here strengthen confidence in our findings. The observed gamma-induced changes in hardness, hydrophilicity and ion release are not only statistically significant, but also of substantial magnitude, underlining their potential clinical relevance.

Within the limitations of this study, a 15 kGy gamma dose emerges as a promising sterilization level that achieves sterility while limiting adverse alterations to implant properties. In comparison, although effective for sterilization, the standard 25 kGy dose significantly compromises mechanical hardness and dramatically increases ion release, which could negatively affect implant longevity and biocompatibility. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing gamma-ray sterilization parameters for dental implants. While achieving sterility remains paramount, preserving Ti mechanical strength, surface morphology and biocompatibility is essential for ensuring long-term clinical success. Adopting a 15 kGy dose offers a promising balance between microbial safety and material preservation, potentially improving implant longevity and patient outcomes.

Conclusions

This study shows that gamma-ray irradiation at 15 kGy and 25 kGy significantly influences SLA-treated Ti implants. The results indicate a reduction in surface hardness, alterations in surface morphology, the enhancement of hydrophilicity, and an increase in Ti ion release. Notably, a 25 kGy dose induces considerable surface micro-damage, leads to excessive ion release, exceeding the established safe limits, and results in substantial mechanical degradation, which may jeopardize long-term implant stability and biocompatibility. In contrast, a 15 kGy dose effectively achieves sterilization while mitigating adverse effects, maintaining surface hardness closer to clinically acceptable thresholds, and ensuring that ion release remains within safe parameters.

While this research is constrained by the absence of quantitative surface roughness measurements and focuses on short-term in vitro evaluations, the findings suggest that a sterilization dose of 15 kGy strikes an advantageous balance between achieving sterility and preserving critical implant surface and mechanical properties. Further studies incorporating quantitative roughness profiling, in vivo evaluations and long-term assessment are essential to validate these conclusions and inform clinical practice.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Language editing was assisted by ChatGPT (OpenAI). All content accuracy and scientific integrity were independently verified by the authors.