Abstract

Background. The technique described in this study has been used by our group for approx. 20 years. It involves fabricating a provisional or definitive prosthesis over a metal structure made of several wing abutments that can be intraorally welded to connect the adjacent implants.

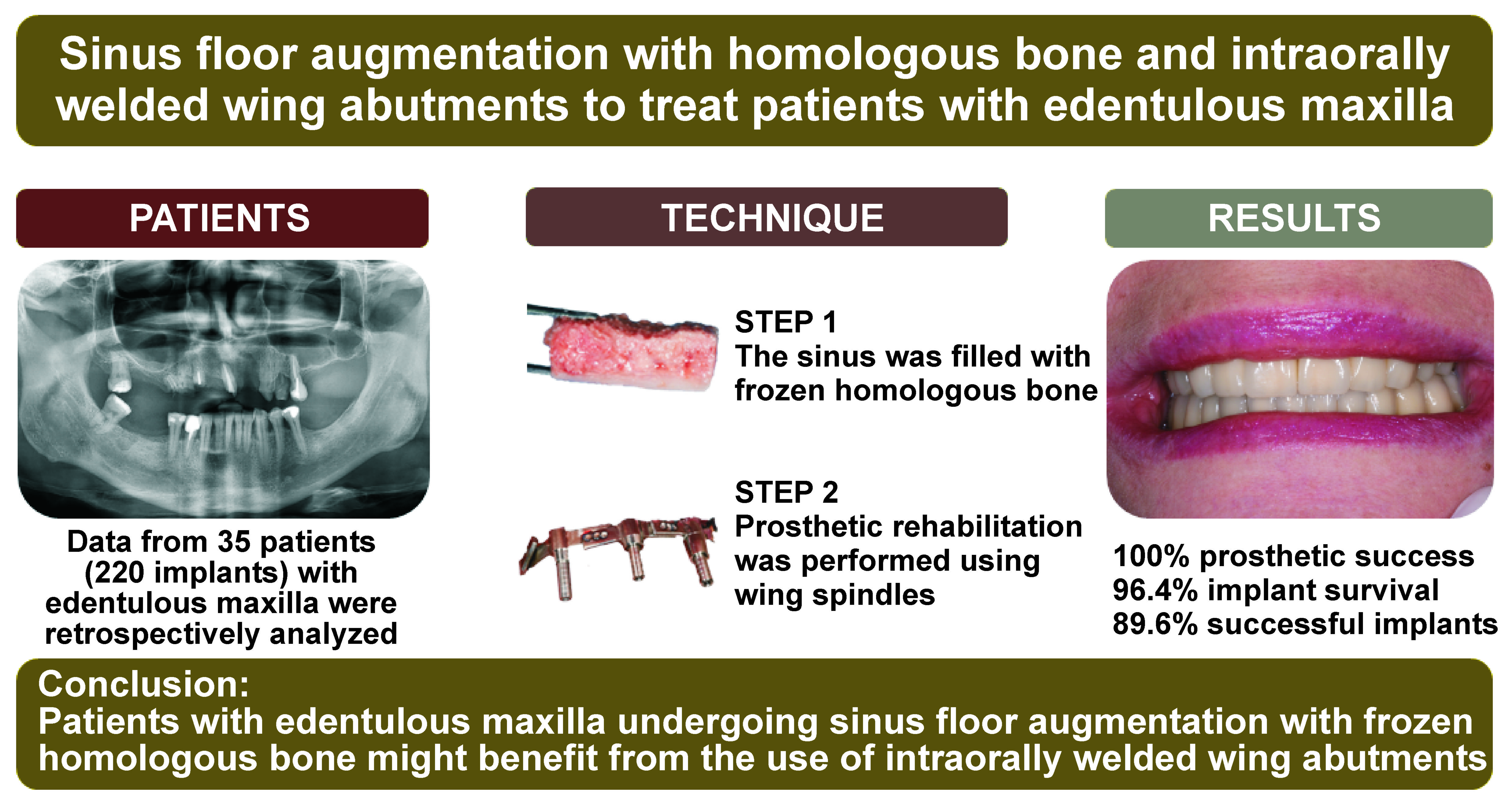

Objectives. The aim of this retrospective observational study was to evaluate the effectiveness of and the complications associated with the use of intraorally welded wing abutments in patients with edentulous maxilla undergoing sinus floor augmentation with frozen homologous bone.

Material and methods. Data from adult patients diagnosed with edentulism in the posterior maxilla were retrospectively analyzed. All patients underwent sinus augmentation with homologous bone and were rehabilitated for 5–6 months after surgery, using wing spindles. The primary outcome of the study was to evaluate the prosthetic success, while the secondary outcomes included the assessment of the implant success and the incidence of complications.

Results. Data analysis included 35 patients, corresponding to 220 implants. At the last follow-up, a 100% prosthetic success and a 96.36% implant survival rate were obtained. A total of 8 patients (22.86%, corresponding to 8.64% of total implants) experienced complications, such as radiographic radiolucency, peri-implantitis and implant mobility.

Conclusions. The results of this retrospective study suggest that patients with edentulous maxilla undergoing sinus floor augmentation with frozen homologous bone might benefit from the use of intraorally welded wing abutments.

Keywords: sinus augmentation, welded wing abutment, edentulous maxilla

Introduction

The rehabilitation of edentulous patients is usually managed by using prostheses supported by multiple implants,1 which can be splinted with a titanium bar to achieve better performance.2 This approach allows to increase the mechanical stability of implants,3, 4 ultimately reducing the risk of implant and prosthetic failure.5

Since the placement and modeling of the bar can be challenging, the pair-by-pair splinting of the adjacent implants can be a valuable alternative facilitating the whole procedure. This can be done resorting to wing abutments, which are welded intraorally. Their application has already proven to be a viable approach for the rehabilitation of both partially and totally edentulous patients, even in immediate loading scenarios.6, 7

In principle, the mechanical stability provided by wing spindles could be advantageous also for patients needing sinus floor augmentation, a commonly used technique when the residual bone height of the posterior maxilla is less than 4 mm.8 This approach consists in opening a lateral window to access the sinus cavity, displacing the sinus membrane, and finally filling the cavity with a bone substitute.9, 10, 11

Having osteoinductive, osteoconductive and osteogenic properties, as well as no risk of immunological rejection or disease transmission, autologous bone might be regarded as the most suitable bone graft. However, given the invasiveness and potential complications associated with the sampling of autologous bone,12 heterologous and homologous grafts represent valuable alternatives13, 14, 15, 16 with proven osteoconductive capabilities.17 While requiring some processing, such as freezing, lyophilization and demineralization, allogenic bone has a long history of use for bone augmentation and has proven to be comparable to autologous bone.13, 18, 19, 20

By combining the aforementioned techniques, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of and the complications associated with the use of wing spindles in patients with edentulous maxilla undergoing sinus floor augmentation with frozen allogenic bone.

Material and methods

Study design and patients’ characteristics

This was a retrospective, observational, monocentric study evaluating the clinical records of patients treated at the Authors’ clinic between 1997 and 2019. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1.

The study protocol was assessed and approved by the relevant ethics committee (Comitato Etico per le Sperimentazioni Cliniche (CESC) della Provincia di Vicenza, Italy; approval No. 66/22). All procedures were performed in accordance with the good clinical practice (GCP) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Allogenic bone processing

Allogenic bone was provided by Fondazione Banca dei Tessuti del Veneto (FBTV; Treviso, Italy), an institution accredited by the Italian National Transplant Centre for the retrieval, processing, storage, and distribution of human tissues for transplantation. Tissue donors were selected according to the Italian directives, which stipulate donor anamnesis and blood testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 and HIV-2 antibodies (Ab), human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus (HTLV)-1 and HTLV-2 Ab, hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen and anti-core Ab, hepatitis C virus (HCV) Ab, and syphilis. Screening also included cytomegalovirus Ab, and nucleic acid amplification tests (NAT) for HIV, HBV and HCV. Tissues were retrieved within 24 h from cardiac arrest and processed under class A laminar flow hoods. Bone blocks were obtained from the iliac crests and decontaminated in a validated antibiotic.21, 22 Afterward, the bone blocks were stored at −80°C. Several microbiological tests were carried out throughout the processes, and only uncontaminated tissues with excellent morphology were distributed for clinical implantation.

Description of the surgical procedure and implant placement

After clinical examinations and radiographic asessments using intraoral radiographs and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), the diameters, lengths and positions of the implants were pre-planned on the CBCT scans, and a surgical guide was manufactured.

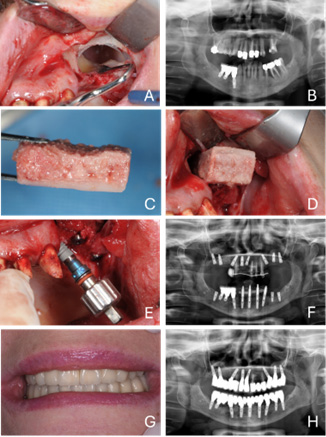

The patients were prescribed antibiotic prophylaxis (2 g amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Augmentin); GlaxoSmithKline, Verona, Italy) 1 h before surgery and every 12 h for 8–10 days after surgery. The surgical procedure was carried out under local anesthesia with articaine hydrochloride (40 mg/mL) and epinephrine (1:100,000) on the vestibular and palatal sides. Mucosae were cleaned with iodine. The gingiva was incised para-crestally and a full-thickness flap was raised to create an access window on the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus. Access to the sinus was obtained using a round tungsten bur. Then, the sinus membrane was carefully elevated and the window was gently pushed inside the cavity. The procedure was performed under irrigation with sterile saline.

Based on the CBCT scans, the allogenic bone block was shaped with a bur to fit the cavity through a process of trial and error. Once placed in the sinus, the block was simultaneously pressed against the sinus base with a spatula and drilled through the bone ridge to accommodate the implant. Then, the bone ridge and the bone block were further drilled following the drill sequence recommended by the implant manufacturer, while keeping the block pressed against the sinus base with a spatula. Afterward, the implants were placed using the guide, sealed with a cover screw, and the gingiva was sutured.

When required, implants were placed in native bone to rehabilitate mesially located edentulous gaps, whereas posterior implants were stabilized using sinus grafting. The implants were 10-11.5-13-15 mm long and 3.25 or 4 mm wide. All implants were of the same brand and from the same manufacturer (BTK®; Biotec, Povolaro, Italy), featuring a tapered design with a sand-blasted, double-etched surface.

Prosthetic rehabilitation

All patients were rehabilitated for 5–6 months after surgery, using wing spindles (Wings®; T.A.B., Borso del Grappa, Italy), which are available in different heights (1.7, 2.7 and 4.5 mm). The wing spindles were connected to the implants through 20-mm-long screws and their lateral ‘wings’ were cut at the desired length to partially overlap those of the adjacent implants. Finally, the wing spindles were welded intraorally.

The resulting metal structure constituted the internal reinforcement of the prosthesis. This was fabricated by first taking an alginate impression of the sub-structure to create a cast. Based on this metal structure, the technician prepared the definitive prosthesis, using a composite resin. Lastly, using the same composite resin, the screw holes were filled.

More details on the pair-by-pair splinting technique can be found elsewhere.6, 7

Control visits

Patients underwent ortopantomography (OPG) and sinus augmentation at baseline (T0). A second OPG was taken 5–6 months later, when the prosthesis was delivered (T1). Further OPGs were scheduled at variable intervals based on individual needs; regardless of these additional assessments, an OPG was obtained for each patient at 12 months from baseline (T2). At each follow-up visit, the prosthesis was unscrewed to facilitate proper hygiene for the patient. This also enabled the assessment of implant osseointegration, and the detection of any signs of peri-implantitis or mucositis.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was to evaluate the prosthetic success. A prosthesis was deemed successful if none of the following events occurred: prosthesis unscrewing, chipping or fracture; screw loosening or fracture; or welding point fracture.

The secondary endpoint consisted in the assessment of implant survival with respect to the marginal bone loss (MBL), as well as the implant success evaluated according to the Albrektsson and Zarb criteria. These criteria included: the absence of persistent pain, dysesthesia or paresthesia in the implant area; the absence of peri-implant infection with or without suppuration; the absence of perceptible implant mobility; and the absence of more than 1.5 mm or peri-implant bone resorption during the first year of loading or 0.2 mm/year of resorption during the following years. The implants were considered successful when all the abovementioned conditions were met.

In addition, the incidence of complications (the loss of implant, peri-implantitis, pain, edema, or other adverse events) was recorded.

MBL measurement

For all the included records, the intraoral radiographs were digitally scanned, converted to 600 dpi resolution TIFF images, stored on a personal computer, and analyzed using image analysis software (ImageJ, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, USA; https://imagej.net/ij) to measure the peri-implant MBL. The process was as follows: after loading each image, the software was calibrated using the known implant diameter at the most coronal portion of the implant neck; then, the distance from the implant–abutment interface to the most apical point of crestal bone in intimate contact with the implant was measured to the nearest 0.01 mm on both the mesial and distal sides. These 2 measurements were averaged to obtain a single peri-implant MBL value. The MBL for each implant at the final follow-up visit was calculated by subtracting the baseline peri-implant bone level (measured at implant insertion) from the bone level at the follow-up time point.

Bias

To mitigate potential bias from the fact that the patients were treated exclusively by one of the authors (SD), the selection of clinical records and data extraction were performed by other authors (FM, NZ). Additionally, to further address any possible sources of bias, an independent biostatistician conducted the statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Since the study aimed to investigate the prosthetic success using descriptive statistics, no sample size calculation was performed. Thus, the study population size corresponds to the number of records that met the inclusion criteria.

Absolute and relative frequencies were used to describe categorical variables (the patients’ age, sex, the prosthetic success, the implant success, and complications), while mean and standard deviation (M ±SD), and median and interquartile range (Me (IQR)) were used to report continuous variables. Normality was checked by means of the Shapiro–Wilk test. All analyses were performed in Origin 2022 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA).

Results

The study included 35 patients (N = 35), 19 males (54%) and 16 females (46%), with a mean age at surgery of 55.1 ±7.1 years (range: 42–67 years). The total number of implants was 220, of which 60 were placed in native bone and 160 in allogenic bone. Half of the implants (n = 110) were placed in the right and left maxilla, and the number of implants in each patient was distributed as follows: 8 patients (22.86%) received 7 implants; 6 patients (17.14%) received 8 implants; 6 patients (17.14%) received 6 implants; 5 patients (14.29%) received 3 implants; 3 patients (8.57%) received 4 implants; 2 patients (5.71%) received 10 implants; 2 patients (5.71%) received 5 implants; 1 patient (2.86%) received 12 implants; 1 patient (2.86%) received 9 implants; and 1 patient (2.86%) received 2 implants. The mean follow-up period was 122.2 ±68.0 months (range: 25–296 months) after implant insertion. The patients’ characteristics and rehabilitation details are summarized in Table 2.

The prosthetic success was obtained in all patients (N = 35; 100%,), with an implant survival rate of 96.36% (n = 212). According to the Albrektsson and Zarb criteria, 197 implants (89.55%) were successful. The average MBL was 0.89 ±0.54 mm (range: 0.12–2.79 mm).

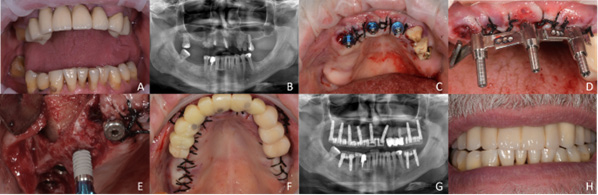

Complications were observed in 8 patients (22.86%), corresponding to 8.64% (n = 19) of delivered implants. All complications except one occurred in the implants placed in allogenic bone. Specifically, non-early osseointegration involved 3 implants (1.36%), radiographic radiolucency – 8 implants (3.64%), peri-implantitis – 4 implants (1.82%), and implant mobility – 1 implant (0.45%). Moreover, 1 implant delivered to a non-smoking patient was lost after 57 months due to peri-implantitis. Another patient with previous chronic periodontitis, recurrent bleeding and a significant muscular strength/chewing force, lost 2 implants after 115 months. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show 2 different cases which were successfully rehabilitated with the proposed technique.

Discussion

Taking into account a 100% prosthetic success and an implant survival rate of 96.36%, the results of this retrospective study suggest that patients with edentulous maxilla undergoing sinus floor augmentation with frozen allogenic bone might benefit from the use of wing abutments.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the implant survival rate obtained in this study appears to be similar to, or even higher than those observed in the scarce literature reporting on similar procedures. Indeed, Avvanzo et al., who retrospectively evaluated the survival rate of intraorally welded implants delivered in patients undergoing either sinus augmentation or crest splitting, found that the 1-year survival rate in the group undergoing sinus lift was 83.4%.23 While sample sizes are quite different (21 vs. 220 implants), the higher survival rate observed in the present study (96.36%) might be also ascribed to the welding of wing abutments rather than titanium bars as one of the existing differences between the compared studies.

More in line with the herein presented results, Rizzo et al. reported a 97.7% survival rate of the implants placed immediately after transcrestal sinus augmentation with fresh-frozen allogenic bone blocks.24 Similarly, Kim et al. obtained a 97.06% failure-free survival rate at 1 year after implant placing and sinus augmentation.25

Nevertheless, it must be said that the implant success rate observed in the present study (89.55%) seems to be lower than that achieved when intraorally welded titanium bars are used in fully or partially edentulous patients not undergoing sinus augmentation, and in arches area other than the posterior maxilla. Indeed, when investigating such clinical scenarios, Degidi et al. achieved very high implant success rates, which were close to 100% both at 1 and 2 years of follow-up.4, 26

The combination of the herein proposed techniques also proved to be safe, as most of the recorded complications were related to radiographic radiolucency, which is generally considered an artifact caused by beam hardening.27 Moreover, soft-tissue complications, such as peri-implantitis, occurred only in patients with a previous clinical history of recurrent periodontitis.

The results of this study align with previous retrospective analyses evaluating the success and complication rates of the pair-by-pair splinting technique for rehabilitating completely edentulous patients.6 In those patients, the prosthetic success rate was 100%, and the implant survival rate was 97.2%.6 This study not only supports the viability of the technique, but also extends its application to patients requiring sinus floor augmentation. Notably, the technique is straightforward and quick to perform, as wing abutment extensions come in different angles, allowing the metal frame to be shaped according to each patient’s specific anatomy. Additionally, this approach is more cost-effective as compared to other rehabilitation procedures, making it a viable option with acceptable esthetic and functional outcomes for those unable to afford more expensive treatment.

Besides its retrospective nature, the main limitations of the present study include the heterogeneous dimensions and number of implants per patient, as well as the evaluation of a follow-up period with a wide range. Prospective and/or comparative studies will be necessary to assess the effectiveness and safety of the proposed approach without relevant bias.

Conclusions

Within its limitations, the results of the present study suggest that the rehabilitation of patients with edentulous maxilla requiring sinus floor augmentation can be safely and successfully performed by combining the use of frozen allogenic bone with intraorally welded wing abutments.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was assessed and approved by the relevant ethics committee (Comitato Etico per le Sperimentazioni Cliniche (CESC) della Provincia di Vicenza, Italy; approval No. 66/22). All procedures were performed in accordance with the good clinical practice (GCP) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.