Abstract

Background. The number of patients with bone defects is increasing. The treatment of damaged bones or bone defects is essential. Bone graft materials are frequently used in bone repair procedures. Researchers are attempting to replace damaged or defective bones with artificial ones, while also striving to improve the mechanical and biological compatibility of the scaffolds.

Objectives. The study aimed to establish and validate novel demineralized freeze-dried bovine bone xenograft nanoparticles (DFDBBX-NPs) for enhancing bone repair.

Material and methods. Demineralized freeze-dried bovine bone xenograft nanoparticles were extracted from bovine femoral bone. The physicochemical and biochemical properties of both native and demineralized freeze-dried materials were evaluated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were utilized to determine the content of type 1 collagen (Col-1) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2), water content percentage (WCP), and enzymatic degradation.

Results. The physicochemical analysis revealed non-porous DFDBBX-NPs with near spherical shapes of various sizes. The dried sample presented the nanoparticles agglomerated together, with an average size of 10–50 nm. The nanoparticles exhibit a type IV isotherm with an H3 hysteresis loop. They have a BET-specific surface area of 3 m2/g and a pore diameter of approx. 5.9 nm. The bioactive content of BMP-2 was higher than that of Col-1 in the DFDBBX-NPs. The DFDBBX-NP scaffold exhibited a slow rate of enzymatic degradation (0.098–0.240% over 14 days) and high water absorption (WCP ~202–215%).

Conclusions. Demineralized freeze-dried bovine bone xenograft nanoparticles demonstrated remarkable potential for the development of new bone grafts.

Keywords: bone graft, demineralized bovine bone, osteogenic, bone regeneration

Introduction

Bone grafting is one of the most commonly performed tissue transplantation procedures. Bone graft materials are widely used to repair bone defects resulting from various pathological conditions.1, 2 In dental practice, bone damage can be attributed to numerous factors, including tumors, cysts, periodontitis, or trauma. Therefore, there is an increasing demand for research on the development of bone graft materials. An ideal bone graft material must be osteoinductive, biocompatible, osteoconductive, bioresorbable, porous, easy to use, mechanically resistant, cost-effective, and have a bone-like structure. Several types of bone grafts are available, namely autografts, allografts, xenografts, and alloplasts.3, 4, 5 Autografts are considered the gold standard in bone grafting because they contain viable bone cells that contribute to osteogenesis and release growth factors that promote osteoinduction.6, 7 Although autogenous grafts are currently employed in dentistry, their usage requires a second surgery. The development of bone graft substitutes is therefore necessary to reduce the complexity of bone extraction for autograft.8, 9 These issues and the shortcomings of allogeneic transplantation, such as the transmission of possible infections and the lack of osseointegration with host tissues, have prompted researchers and clinicians to explore novel graft solutions using challenging biomaterial techniques.10

Biomaterials are being continuously developed as an alternative option to restore damaged bone tissue. Xenograft was designed to overcome the disadvantages of autografting, regarded as the gold standard. Xenografts have similar structure to human bone and are abundant in resources. A demineralized freeze-dried bovine bone xenograft (DFDBBX) facilitates osteoconduction, thereby promoting the regeneration of alveolar bone. Recent studies have reported that deproteinized bovine bone mineral (DBBM) has poor biodegradation properties.11, 12 Researchers started focusing on the regeneration of bone tissue in a potential 3D scaffold, a field of study known as bone tissue engineering (BTE).13, 14, 15 Demineralized freeze-dried bovine bone xenograft nanoparticles (DFDBBX-NPs) have been developed as alternative bovine-derived bone substitutes. These nanoparticles are produced through the demineralization of bovine bone, which removes the inorganic mineral phase while preserving organic components that contain osteoinductive growth factors, such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs). The ideal scaffold should exhibit optimal compatibility, be non-toxic to cells and biodegradable. For this reason, a physical and chemical characterization of DFDBBX-NPs is necessary.

Material and methods

Synthesis of DFDBBX-NPs

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia (approval No. 176/EC/KEPK/07/2022). The demineralized freeze-dried bovine bone was derived from bovine femoral bone after removal of all adherent soft tissues. The bone was cut into fragments measuring 3 mm × 3 mm, and washed using hydrogen peroxide solution to ensure complete removal of blood and any residual fatty tissue. Subsequently, the samples were rinsed in a solution of sodium chloride (NaCl) and aquadest to remove residual peroxide, and soaked in 1% hydrogen chloride (HCl) solution for 24 h, until the minerals disappeared. The samples were freeze-dried using a lyophilizer system (FreeZone® 4.5; Labconco Corporation, Kansas City, USA).

Characterization of DFDBBX-NPs

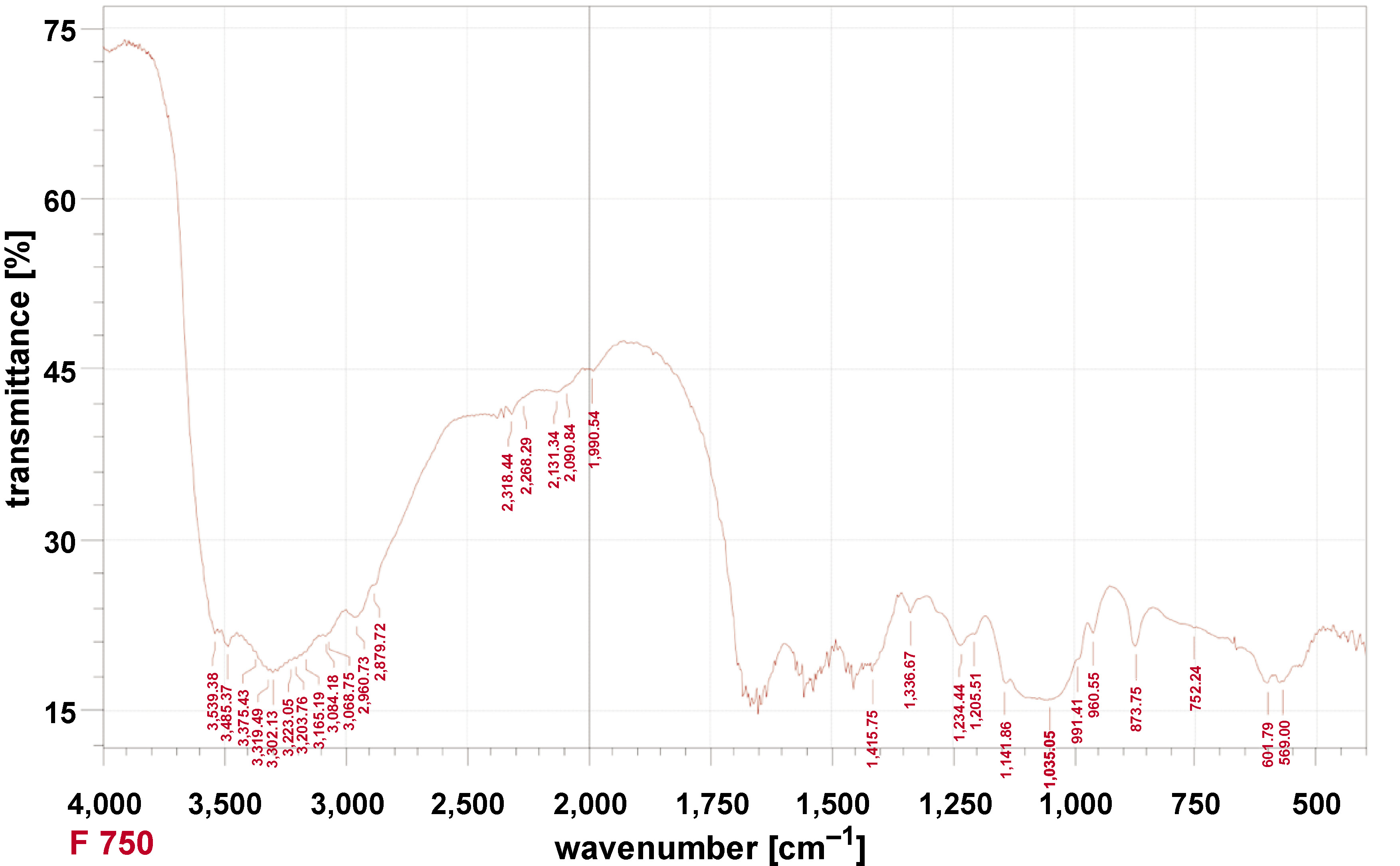

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of the samples was conducted using a spectrometer (Thermo Scientific™ Nicolet™ iS10; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) at a scanning range of 400–4,000 cm−1 and with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were carried out using powder diffraction (X’pert3 Powder; Malvern Panalytical Ltd, Malvern, UK). The obtained XRD pattern was compared to the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) patterns. The analysis was performed on an XRD machine (D8 ADVANCE; Bruker, Billerica, USA).

Surface morphology

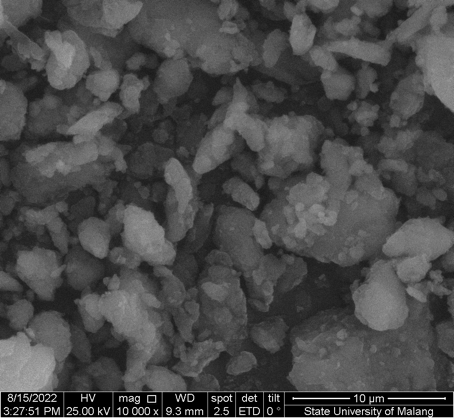

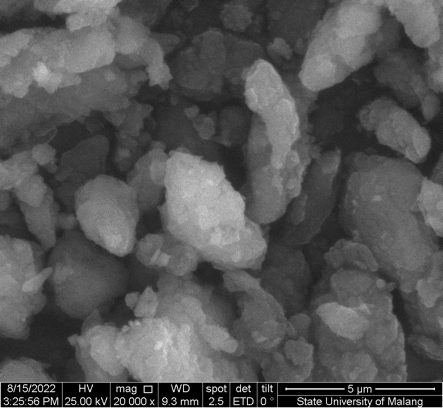

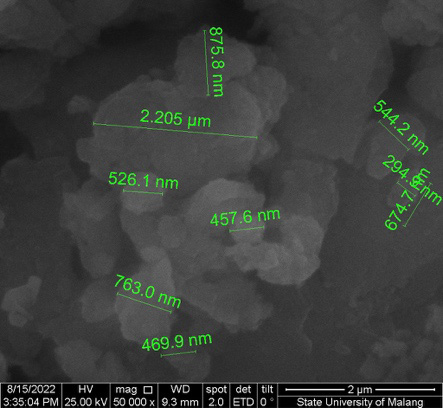

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images of the samples were obtained using a FlexSEM 1000 microscope (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). A Leo 1450VP microscope (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to further evaluate the morphology and size of the nanoparticles. Samples were mounted directly onto aluminum stubs, to which a gold coating was applied prior to examination. Micrographs were recorded at magnifications of ×10,000, ×20,000 and ×50,000.

Survey area and pore size analysis

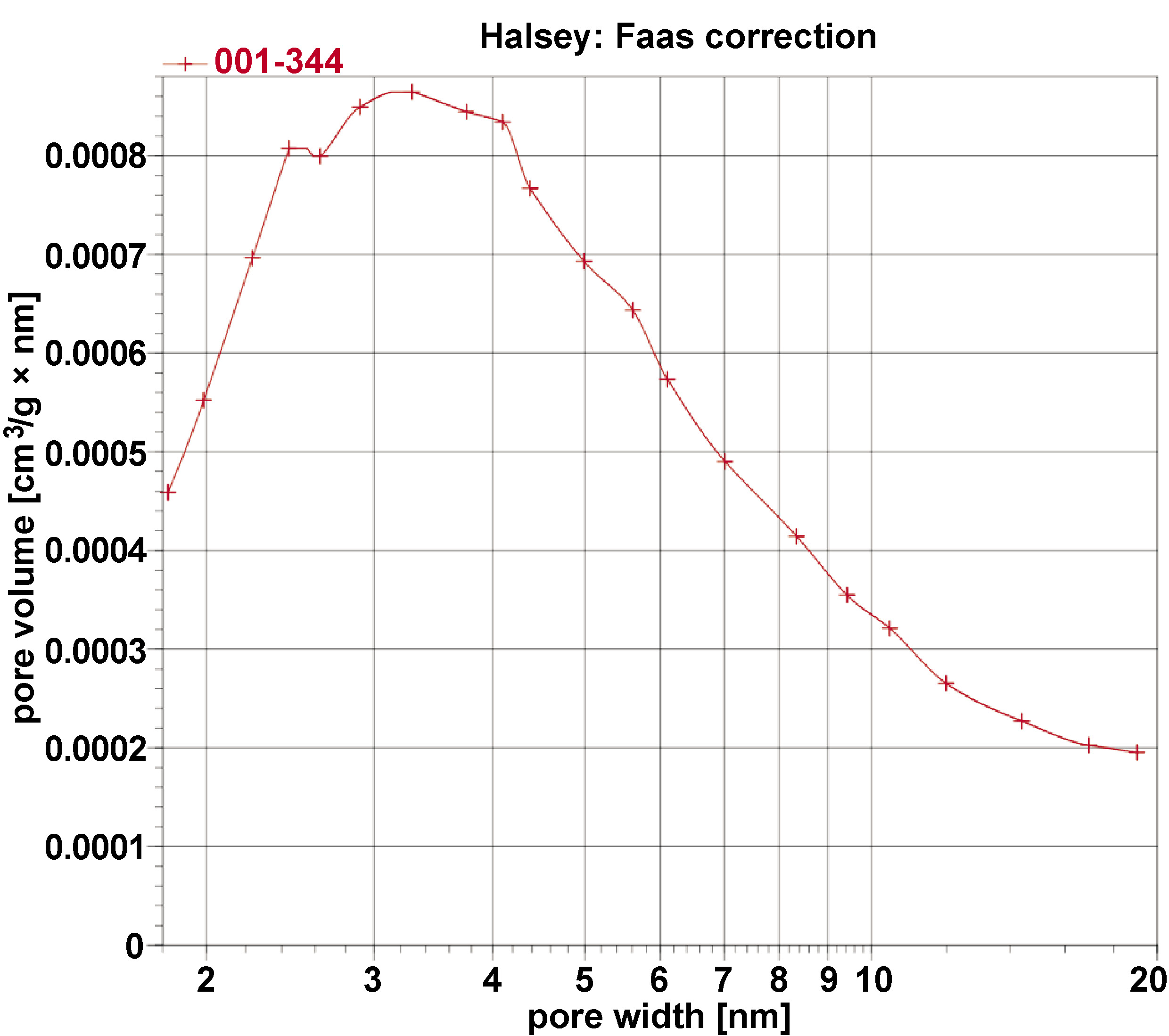

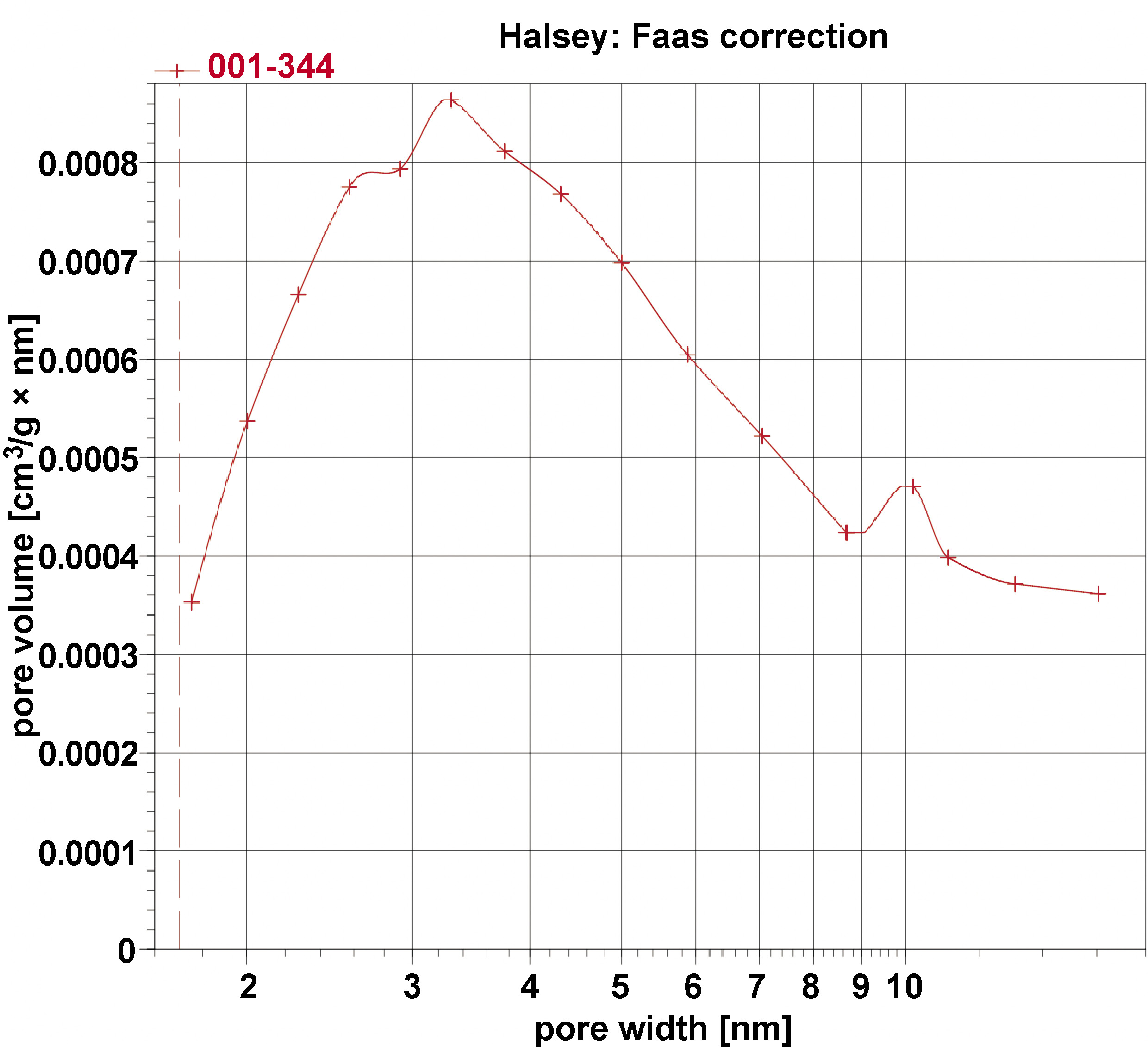

The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area of the samples was measured using a BELSORP-mini II (BEL Japan, Inc., Toyonaka, Japan) based on nitrogen gas adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K and evaluated using the BET equation. Demineralized freeze-dried bovine bone xenograft nanoparticles were inserted into a sample holder, heated and degassed using a sample cleaning station to clean the samples. Next, liquid nitrogen was poured into a dewar for the subsequent analysis with a gas pycnometer (AccuPyc III; Micromeritics®, Norcross, USA). The BET-specific surface area, adsorption–desorption isotherms, pore diameter, and pore volume were recorded. The Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) desorption method was used to determine the pore diameter and volume of the samples.

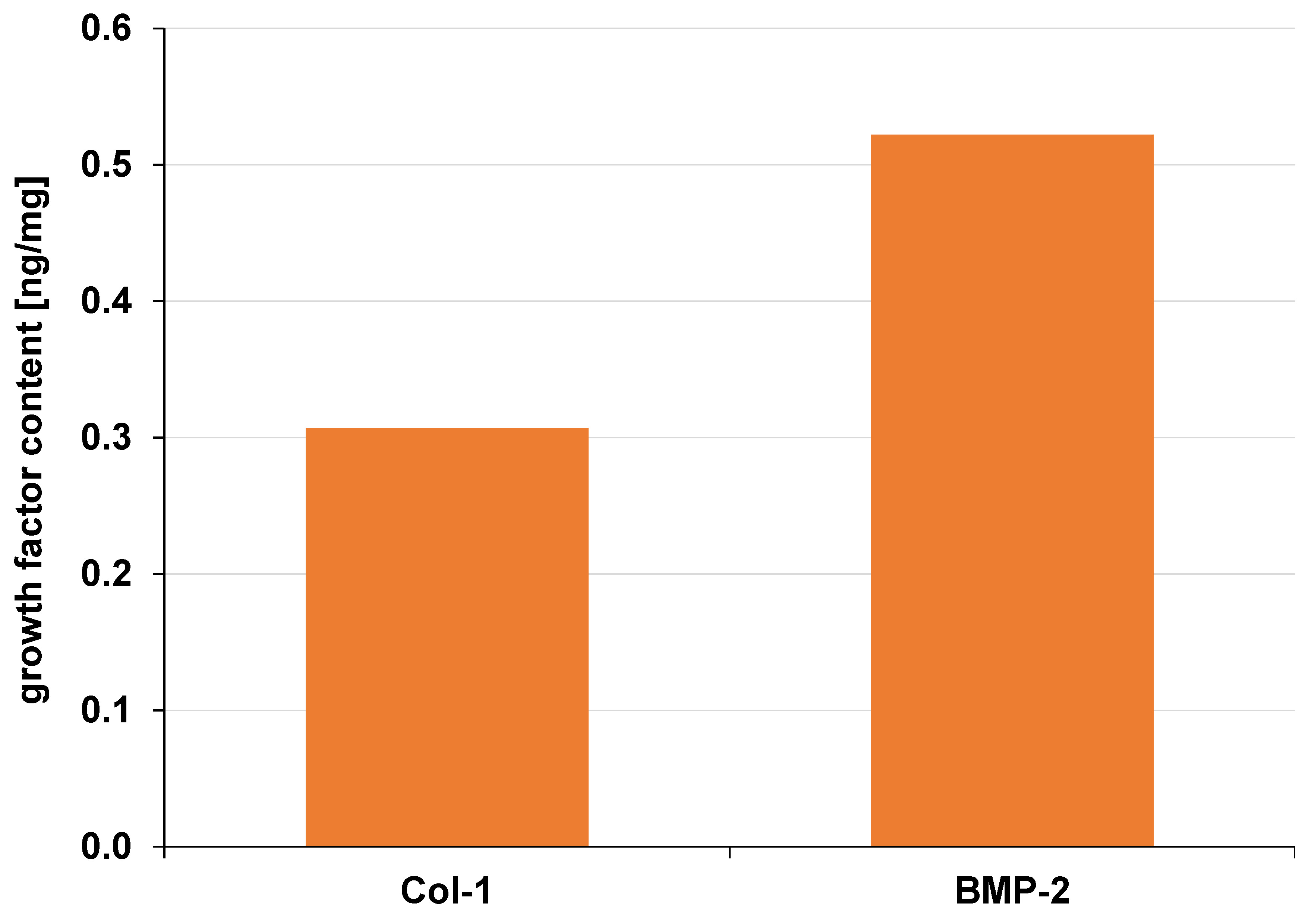

ELISA testing

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (type 1 collagen (Col-1): E1378; BMP-2: E2240) were purchased from Bioassay Technology Laboratory (Shanghai, China). The kits were used to quantify the content of anti-Col-1 and BMP-2 in demineralized and control samples. Briefly, approx. 50 mg of DFDBBX-NPs was transferred into a 50 μL of the extraction buffer. Subsequently, 10 μL of anti-Col-1 antibody and 50 μL of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were added to each of the samples. After incubation at 37°C for 60 min, the plate was unsealed and washed 5 times using wash buffer, followed by 3 freeze–thaw cycles. Then, the samples were sonicated using an ultrasonic tip to extract proteins. The total protein content was determined by means of a microplate reader set (Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 450 nm within 10 min after the addition of the stop solution.

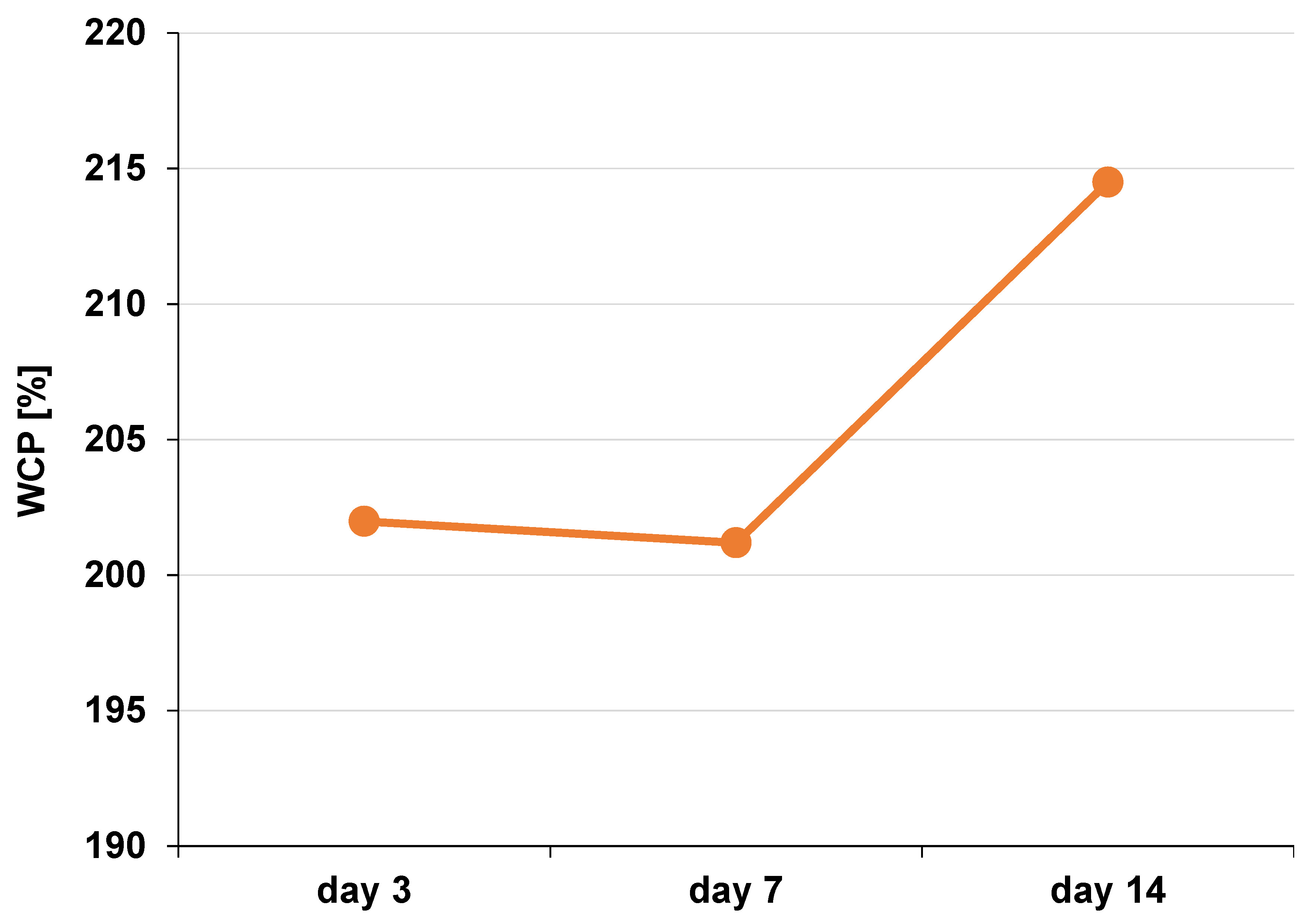

Water content percentage

The scaffold used as a sample was weighed to determine its initial weight (W0). Then, it was placed into an Eppendorf tube and immersed in 1 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) solution (pH = 7.4) for 3, 7 and 14 days at 37°C. Next, the scaffold was slowly extracted using small tweezers to avoid any potential damage, dried with filter paper, and weighed to determine its final weight (Wt). The weight loss was calculated using the following formula (Equation 1):

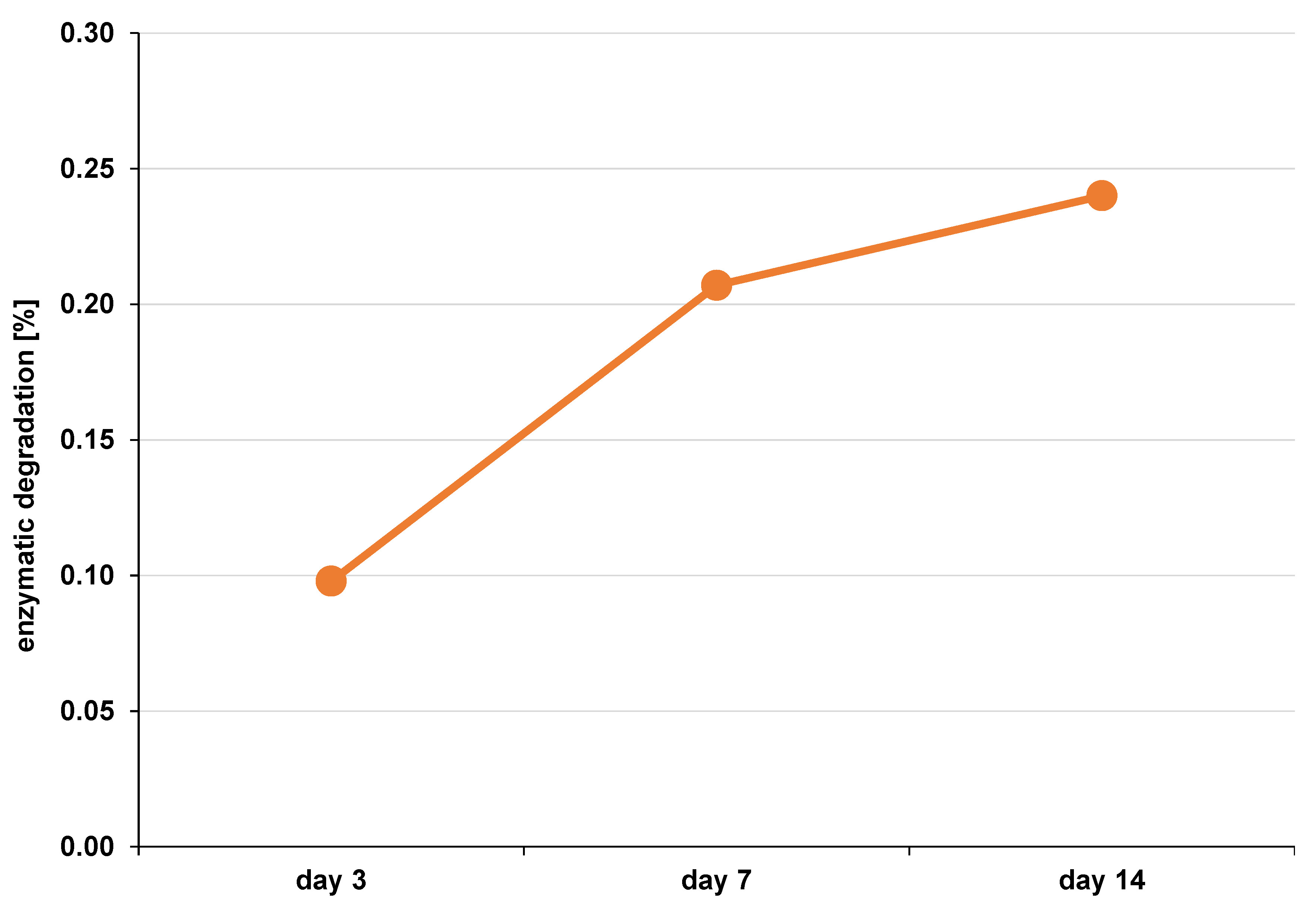

Enzymatic degradation

The second scaffold used as a sample was weighed to determine its initial weight (W0). The scaffold was immersed in 1 mL of solution (PBS and 50 μg/mL collagenase enzyme) for 3, 7 and 14 days. Then, the scaffold was removed from the medium, washed with distilled water, frozen at −80°C, and freeze-dried for 24 h (2 cycles). The final weight (Wt) was recorded. The procedure was repeated for 3 days and 7 days. The degradation rate was calculated using the following formula (Equation 2):

Statistical analysis

The collected data was entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) and analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). Descriptive data was presented as frequency and percentages (n (%)) for categorical variables and as median values with interquartile range (Me (IQR)) for continuous variables. The Kruskall–Wallis test was used to compare the variables between the study groups. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

FTIR analysis

The FTIR of DFDBBX-NPs exhibited the most intense bands at 400–4,000 cm−1, with transmittance values of approx. 70–100%. As shown in Figure 1, the DFDBBX-NPs exhibit prominent absorption peaks at 3,539.38, 3,485.37, 3,375.43, 3,319.49, 3,302.13, 3,223.05, 3,203.76, 3,165.19, 3,084.18, 3,068.75, 2,960.73, 2,879.72, 2,318.44, 2,268.29, 2,131.34, 2,090.84, 1,990.54, 1,415.75, 1,336.67, 1,234.44, 1,205.51, 1,141.86, 1,035.05, 991.41, 960.55, 873.75, 752.24, 601.79, and 569.00 cm−1. Hydroxyapatite (HA) absorption bands were detected in the ranges of 500–700 cm−1 and 900–1,200 cm−1, while collagen-associated bands appeared primarily between 1,200–1,700 cm−1 and 2,800–3,700 cm−1. Carbonate apatite was identified by characteristic bands at 870–880 cm−1 (single band) and 1,400–1,450 cm−1 (double band). The results of FTIR indicate that the absorption peaks at 1,205.51, 1,234.44, 1,336.67, and 1,415.75 cm−1 were attributed to amide III and CH2 bending vibrations of collagen, while the broad bands found at 3,302.13 and 3,319.49 cm−1 were associated with amide A (N–H stretching). Additional peaks in the range of 2,879.72–3,539.38 cm−1 were related to amide A and B vibrations, confirming the presence of Col-1 in the DFDBBX-NPs. These findings indicate that the demineralization process effectively preserved the collagen structure within the scaffold, while the freeze-drying process retained proteins and minerals.

X-ray diffraction

The results of the XRD analysis of DFDBBX-NPs present the chemical composition of the samples (Table 1). Pure HA and brushite were the primary crystalline phases, with HA being the most abundant (69%), followed by brushite (31%). The crystalline phases revealed strong peak characteristics at 2θ values of 11.69°, 21.04°, 25.95°, 29.38°, 30.60°, 31.80°, 34.17°, 37.11°, 39.65°, 46.71°, 49.42°, and 53.29°, with a purity value of 100%.

Surface morphology

As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the resulting particles exhibit non-uniform and irregular morphologies, with evident agglomeration. The formation of agglomerates is attributed to the wide particle size distribution. The aggregation is likely driven by direct interparticle interactions, such as Van der Waals forces or chemical bonds. Figure 4 presents nanosized particles at a magnification of ×50,000. Nanoparticles are generally defined as solid particles with sizes ranging from 10 nm to 1,000 nm. However, pronounced aggregation at this magnification indicates the coexistence of both nano- and microscale particles, making precise size determination difficult and suggesting that only a fraction of the particles fall within the microscale range.

Survey area analysis

The BET surface area analyses of the sample were conducted, and its BET adsorption and desorption isotherms with pore size distribution are given in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The type IV isotherm with an H3 hysteresis loop, based on the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) classification, is indicative of mesoporous materials, which consist of aggregates of plate-like particles, resulting in slit-shaped pores. The BET-specific surface area of the sample is 3 m2/g with a BJH pore diameter of 5.9 nm, and a total pore volume of 0.008680 cm3/g.

Water content percentage

The water content percentage (WCP) in the DFDBBX-NP scaffold was evaluated to determine its capacity for water absorption. The average WCP values are presented in Table 2. Scaffolds with higher water content generally exhibit improved cell infiltration and nutrient transport. The average WCP of the DFDBBX-NP scaffold on the 3rd day was 201.98%; on the 7th day, it was 201.19%; and on the 14th day, it was 214.50% (Figure 7).

Enzymatic degradation

The scaffold was monitored to determine its enzymatic degradation rate. The DFDBBX-NP scaffold exhibited degradation rates of 0.098% after 3 days, 0.207% after 7 days and 0.240% after 14 days of immersion (Figure 8). The mean values are presented in Table 3.

ELISA testing

The BMP-2 content (0.52 ng/mg) in the DFDBBX-NPs was higher than that of Col-1 (0.31 ng/mg) (Figure 9). Demineralized bovine bone xenografts are organic materials with inherent osteogenic potential. They contain bioactive molecules such as Col-1 and BMP-2, which play essential roles in osteoinduction and osteoconduction.

Discussion

The FTIR analysis of the DFDBBX-NPs demonstrated characteristic peaks corresponding to both organic and inorganic components. Absorption bands at 2,593 cm−1 and 2,002 cm−1 indicates interactions between the organic matrix and minerals. The peak at 1,791 cm−1 is attributed to the absorption of the C=O group from the primary amide, whereas the peak of 1,620 cm−1 indicates the deformation of NH2 from amide I and C–N stretching vibrations of the secondary amide. Asymmetric stretching vibrations observed at 1,147 cm−1 and 1,089 cm−1 are associated with the absorption from the PO4 group. The presence of the PO4 group is supported by stretching and bending vibrations with absorption bands at 966 cm−1 and 574 cm−1. Bending vibrations of the CO3 group were identified at 1,456 cm−1 and 873 cm−1. Overall, the FTIR confirms the presence of a mineral matrix primarily composed of phosphate and calcium ions forming HA crystals (Ca10(PO4)5(OH)2), bicarbonate, and an organic phase consisting of the C=O group, CN, C–O–C, and OH.16

The XRD characterization graph of the DFBBX-NPs revealed the presence of HA and brushite. Hydroxyapatite, known in the literature as hydroxylapatite, is a rare natural mineral with the chemical formula of Ca5(PO4)3(OH), which is commonly expressed as Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 to indicate that the crystalline unit cell consists of 2 entities. Due to its chemical similarity to the mineral component of human bone and teeth, HA is widely used, especially as a filling material, to repair bone defects.17 The high crystallinity of HA contributes to its enhanced mechanical strength. However, if the crystallinity is too high, it will be more difficult to absorb it into the body than bone apatite. The crystallinity level of bovine HA can be controlled by adjusting the annealing temperature and holding time during the preparation of HA from bovine.18, 19

The nanoparticles used as delivery carriers must possess controlled morphology, uniform size distribution and high biocompatibility. Agglomeration occurs as a result of clumping during cooling or storage. Such aggregation is very difficult to avoid due to attractive forces between particles that cause it.20, 21 However, sonication can effectively reduce agglomeration by separating particle clusters through cavitation-induced shear forces.

In order to minimize the aggregation of nanoparticles, the use of an appropriate capping agent is required. Capping agents regulate nanoparticle growth, aggregation and physicochemical characteristics. Various capping agents are employed in the synthesis of nanoparticles, including surfactants, small ligands, polymers, dendrimers, cyclodextrins, and polysaccharides. Common examples include polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), bovine serum albumin (BSA), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), chitosan, and plant extracts. Additionally, capping agents enhance the biomedical performance of nanoparticles by reducing toxicity and increasing biocompatibility and bioavailability in living cells.22, 23, 24

The water content percentage reflects the scaffold’s ability to absorb and retain water. In the present study, the swelling ratio graph results with WCP demonstrated comparable trends. The hydrophilicity of the scaffold is essential for interaction with biological fluids and facilitates cell migration into the scaffold. The highest WCP value was observed at 14 days (214.50%). The treatment group exhibited significantly higher hydrophilicity than the control group at 3, 7 and 14 days. Although a slight increase in WCP was observed in the control group between days 3 and 7, the difference was not significant. In the 2nd week, the capacity for water absorption was no longer increasing. Beyond serving as a medium for cell infiltration, the water absorption capacity of the scaffold supports the distribution of nutrients, metabolites and growth factors through the extracellular media. Therefore, hydrophilic properties are essential for successful bone regeneration. Hydrophobic surfaces tend to promote higher protein adsorption. Protein adsorption on the scaffold surfaces facilitates cell attachment by mediating cell signaling through adhesion receptors, particularly integrins. However, excessive hydrophobicity can lead to dense protein deposition on the scaffold surface.25

The enzymatic biodegradation analysis revealed differences in the behavior or pattern of degradation. Over the 14-day observation period, both scaffolds retained more than half of their initial dimensions. An appropriate biodegradation rate is vital to eliminate the need for second surgery. Bone regeneration typically requires at least 6 months, and resorbable scaffolds are expected to function as temporary barriers for approx. 3–4 weeks. Biodegradation is an essential parameter in the occurrence of regeneration. Therefore, synchronization between scaffold degradation and new bone formation is essential to ensure complete resorption upon tissue regeneration. Hydrophilic properties, chemical composition, degree of crystallization, and scaffold geometry influence the degradation rate.26, 27 The FTIR results confirmed collagen as the main component of the scaffold. The incorporation of nanostructured components has been shown to slow degradation by neutralizing acidic degradation byproducts.27 Furthermore, the modulation of chemical composition, surface morphology, and the incorporation of cross-linking agents can be used to tailor the degradation rate.28, 29

The presence of growth factors in DFDBBX-NPs was confirmed in this study. Previous reports indicate that the osteogenic potential of DFDBBX is associated with their protein composition, particularly Col-1 and BMPs.30, 31 In the present study, ELISA analysis demonstrated that the BMP-2 content in the DFDBBX-NPs was higher than that of Col-1. These findings suggest that DFDBBX-NPs possess osteogenic potential. Osteoinduction is primarily driven by BMP activity within the organic bone matrix. The growth factors play a significant role in the osteogenesis of DFDBBX-NPs.30, 31

Conclusions

Results of the present study demonstrated that DFDBBX-NPs are capable of delivering growth factors at physiologically relevant concentrations, supporting their potential application in bone regeneration.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia (approval No. 176/EC/KEPK/07/2022).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.