Abstract

The aim of the present systematic review was to critically evaluate the recommendations from evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPG) and scientific statements (SS), as well as expert consensus, related to the management of oral complications in intensive care unit (ICU) patients.

A search was made in the PubMed, Scopus, Ovid/Cochrane, and LILACS databases, following the CPG identification filters from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). Both scientific repositories and document references were incorporated as well. The critical assessment was performed by means of the AGREE-II instrument (an ideal scenario) for CPG and SS, and using the AGREE-REX instrument for recommendations (ideal and local scenarios).

A total of 13 related recommendations from 4 SS were included. The mean score in AGREE-II was 58.25. The mean AGREE-REX scores were 45.82 and 39.07 for the ideal and local scenarios, respectively. The included recommendations focused on the oral care assessment, and the development of prevention and execution tools with regard to respiratory infections.

There is a lack of CPG following a rigorous methodology that would incorporate recommendations for oral care in ICU. Dentists are responsible for the development and improvement of recommendations from CPG and/or SS to mitigate oral complications in ICU patients.

Keywords: systematic review, intensive care unit, oral health, clinical practice guideline

Introduction

The intensive care unit (ICU) treats critical patients who need immediate and prioritized healthcare.1 Every day, in-patients are received in ICU because of several complications, among which the most common ones are arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).2 However, it is important to highlight that other non-vital health aspects, such as oral health, could affect the quality of life (QoL) in the long term.3 The goal of professional interdisciplinarity in ICU is to cooperate in the decision-making process based on the understanding of the in-patient’s physiology, psychology and general health. It is necessary that ICU in-patients also receive oral care during their stay in hospital.4 In the US, the number of ICU in-patients is estimated to be around 4.1 million per year.5

One of the most common health issues regards the mouth; for example, some patients show frustration for being unable to handle their thirst because of the dry mouth (xerostomia) associated with mechanical ventilation.6 Some authors have reported the presence of plaque, tongue coating, dental caries, halitosis, mucosa lesions, periodontal disease, and residual fungal diseases within the oral cavity in in-patients.3 The frequently observed dental caries might be related to the reduced salivary flow. Such a decrement of saliva is caused by changes in the oral microbiome, which is composed of microorganisms found in human body’s ecosystems, including the oral cavity.7 Similarly, patients with periodontitis could be at 3 times higher risk for nosocomial pneumonia than those without periodontal disease.8 Indeed, elderly patients are those with the highest risk for periodontal colonization by pathogens.9 The influence of oral bacteria on the occurrence of systemic complications has already been studied. Nevertheless, the importance and relevance of bacteria in the development of oral diseases during ICU in-patient stay, and the fact that the deterioration of oral health will affect the patient’s QoL in future, have not been thoroughly discussed yet.

The lack of protocols for oral healthcare in critical care patients in ICU becomes the main reason for which they develop oral complications. Oral hygiene is important for all ICU in-patients. The appropriate oral hygiene is more complex in ventilated patients as compared to non-ventilated ones, who can practice self-care. However, there might be other health disorders that can constraint the the patient’s movements, thus affecting the cleaning task, e.g., arthritis.10, 11 As reported by Kim et al., an oral hygienic care program proved to be successful in ICU patients due to the supervision of the dentist, reducing the plaque index scores and the Candida albicans colonization.12

An oral care assessment for ICU in-patients could determine their oral health status and point to possible actions, which could either prevent or treat oral diseases. Furthermore, an oral care assessment allows to establish protocols or clinical practice guidelines (CPG) for the ICU team, including oral health as a fundamental component of the in-patient’s general health. There is a lack of CPG that would incorporate recommendations for oral care in ICU.

This work pursues to evaluate the reported recommendations within CPG and scientific statements (SS), as well as expert consensus, related to the management of oral complications in ICU patients. The aforementioned evaluation was performed by means of the AGREE-II and AGREE-REX tools.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The PICAR format was used to define the inclusion criteria13:

– Population – ICU in-patients;

– Intervention – any technique, method or strategy to prevent or treat oral sequelae due to stays in ICU;

– Comparator – any comparator;

– Guideline Attribute – CPG or SS from national and international scientific societies or institutions in either English or Spanish; and

– Recommendation – any either evidence-based or expert consensus recommendation of interest was included.

The exclusion criteria were not considered.

Information sources

Secondary database sources (PubMed, Scopus, Ovid/Cochrane, and LILACS), and the ICU-related CPG and SS in repositories from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) were searched. The final database search was made on August 24, 2021. As additional sources, the references cited in the included documents and those in which the documents were cited were also reviewed.

Search strategy

The search for documents was made by using the CPG identification filters from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH),14 together with oral health terms and ICU terms (“dental” OR “oral health” OR “oral hygiene” OR “oral care”) AND (“critical care” OR “intensive care” OR “intensive unit” OR “ICU”). Other types of search fields, different from the CADTH ones, were not applied.

Selection process

The search results were sifted by 2 reviewers based on the title and abstract reading to exclude documents irrelevant with regard to the objective of this systematic review. The full text of the remainder of the results was read by the 2 reviewers to make the final decision about the inclusion, after reaching consensus in cases of disagreement.

Data collection process

Data extraction from the included documents was performed by 2 reviewers independently. To this end, an MS Excel file was used. In cases of disagreement, the full reading of the document was made, and the consensus was reached.

Data items

Information about the development process, for each included CPG or SS, was extracted taking as a reference the AGREE (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation) reporting checklist.15 The extracted variables were objective, population, users toward whom the recommendations are oriented, development team conformation, and conflict of interest.

Synthesis methods

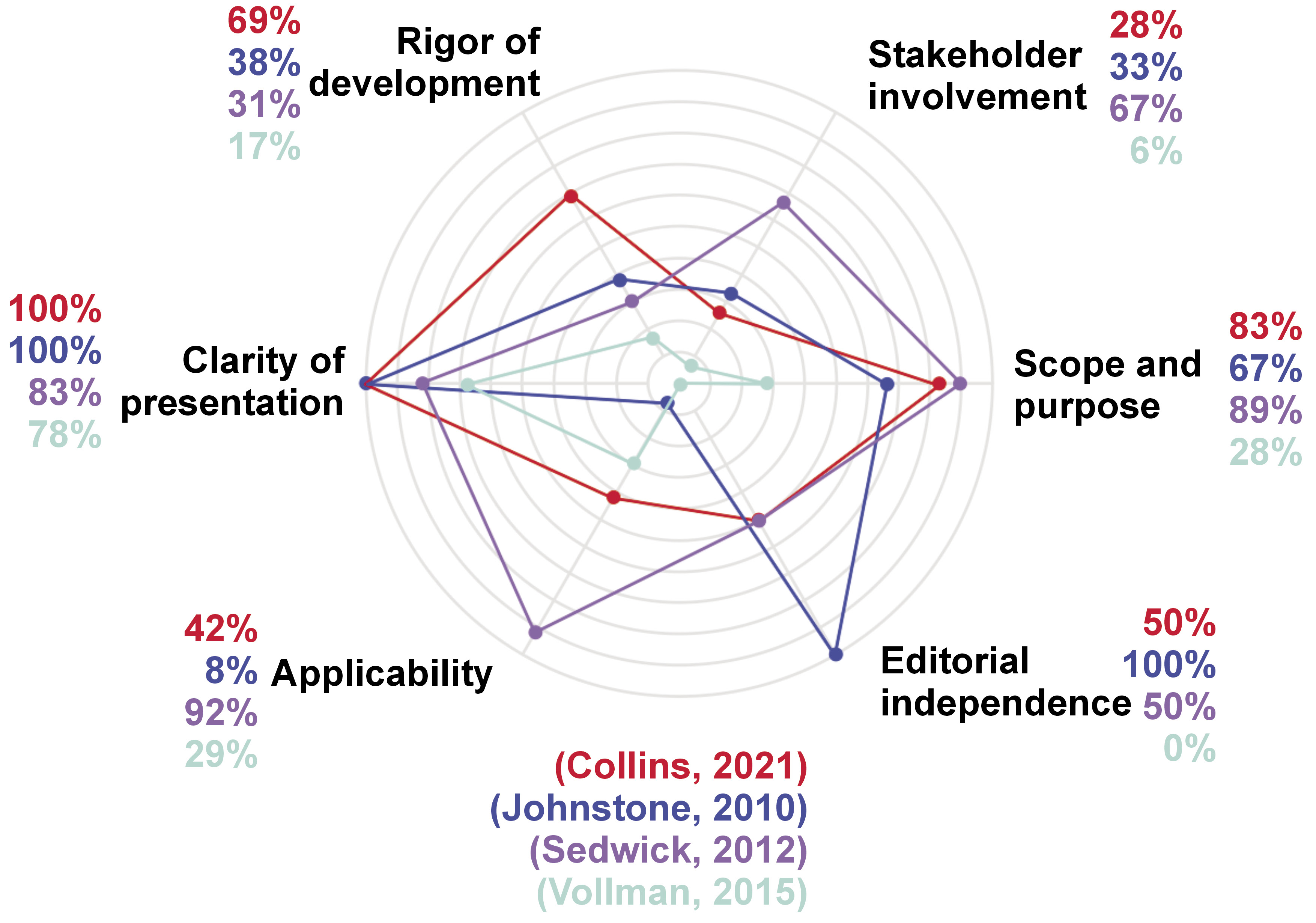

The CPG and SS were assessed by using the AGREE-II tool, which considers 6 different dimensions, i.e., scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, editorial independence, and the overall assessment of the guidelines. A CPG is considered to have high methodological quality when its overall score is greater than or equal to 70 points.16 The overall score for each CPG and SS was presented. In addition, an average score for each of the dimensions was also provided.

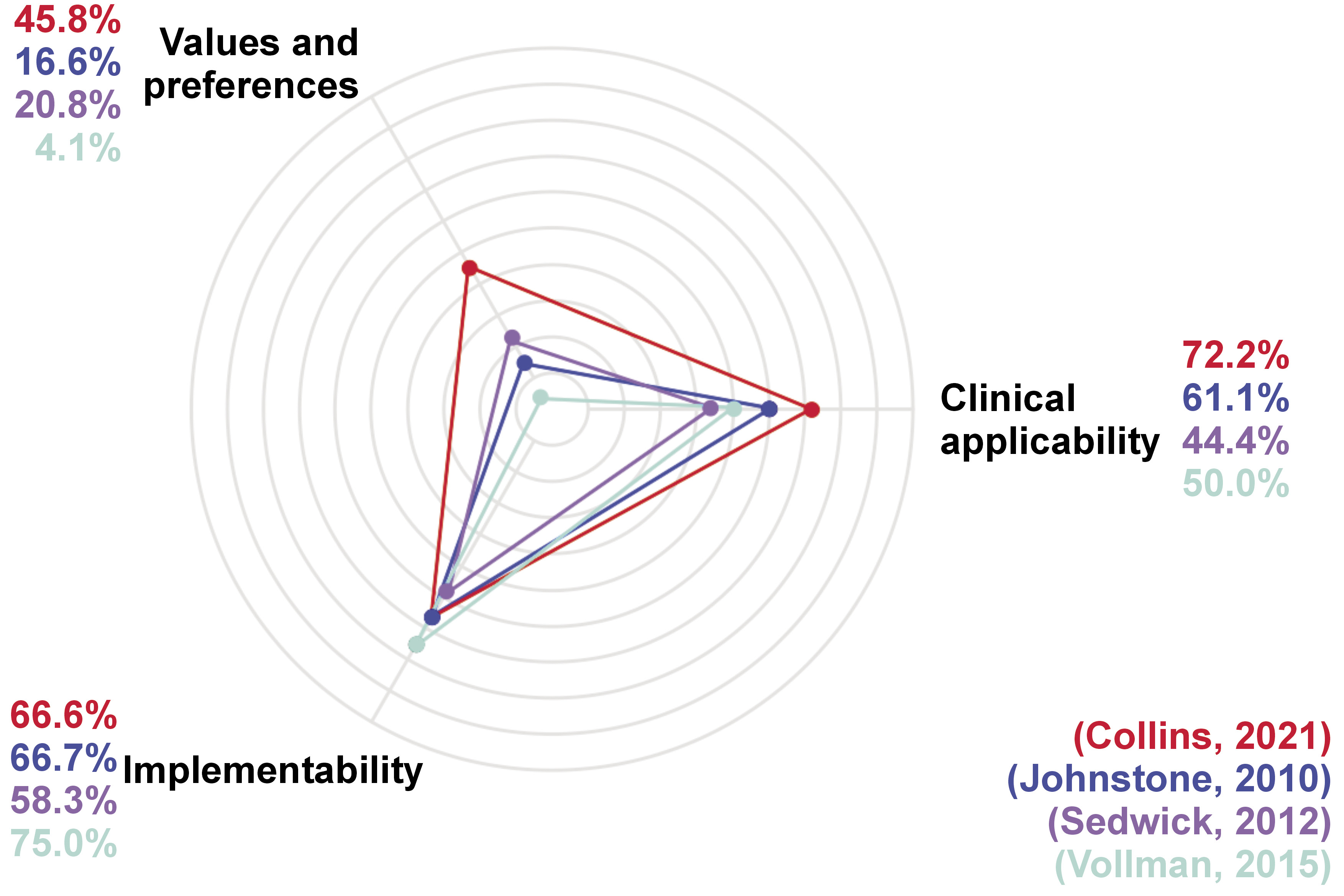

The different practice recommendations were assessed by means of the AGREE-REX tool, which considers 3 main domains: clinical applicability (evidence and applicability to target users and patients/populations); values and preferences (of target users, patients/populations, policy-/decision-makers, guideline developers), and implementability (purpose, and local application and adoption).17 Each recommendation has an overall score in the ideal scenario, which is interpreted as the original scenario for the CPG and SS. Also, an assessment comprising the local scenario was made, corresponding to the Colombian context.

Each CPG was assessed by 2 reviewers independently, whereas all the recommendations were evaluated by the whole review team. The presented scores correspond to the mean value of the reviewers’ scores. Neither CPG and SS nor recommendations were excluded because of their methodological quality.

Results

Study selection

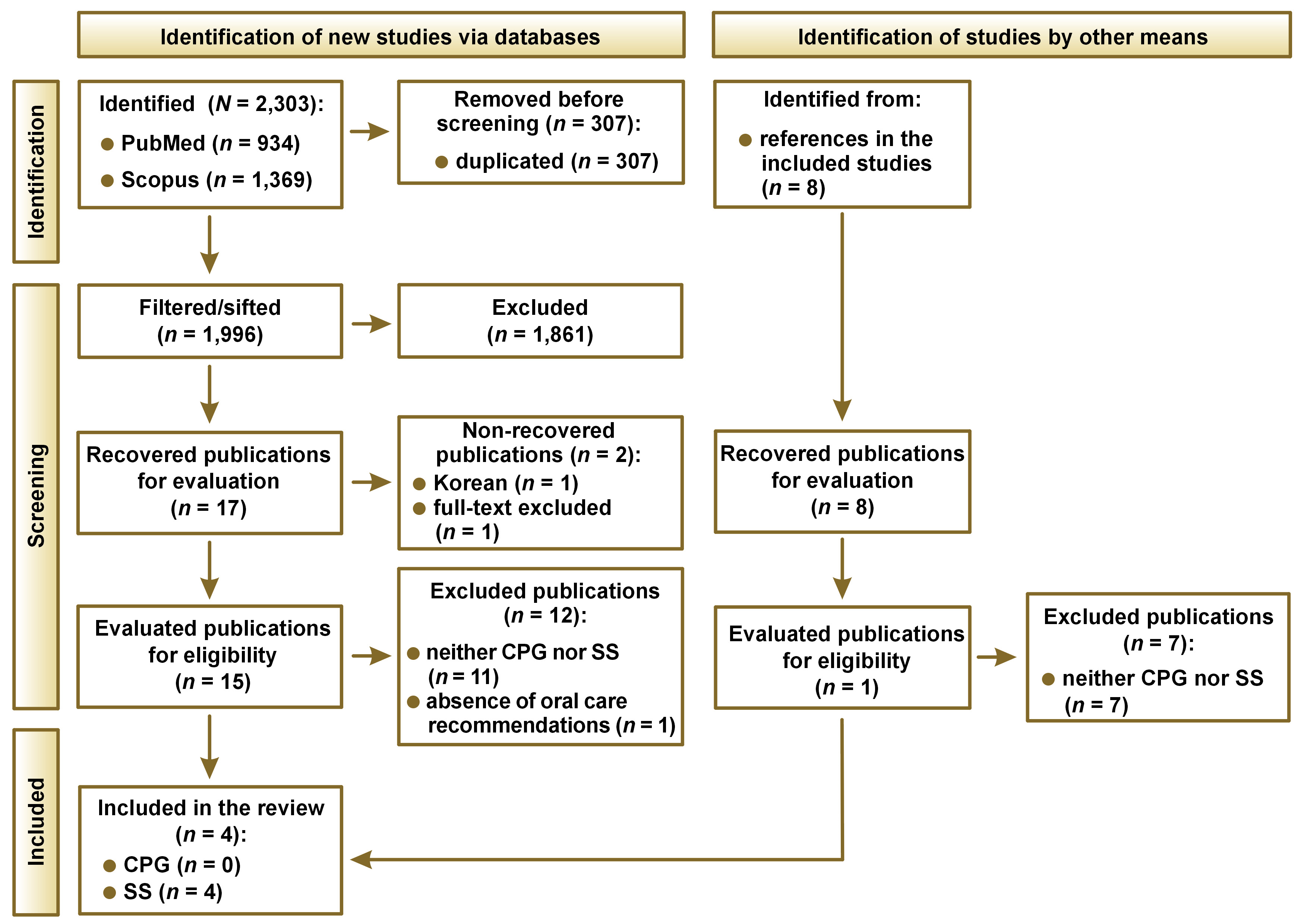

A total of 2,303 articles were identified from the PubMed and Scopus databases. From these 2,303 articles, 307 were duplicated and thus removed from analysis, obtaining a total of 1,996 articles to be sifted. After following the established protocol consisting of title, objective, methodology, and full text review, 17 articles remained. Then, 2 articles could not be recovered, 11 were excluded given that they were neither CPG nor SS, and an additional one was excluded for not having oral-related recommendations. The final 3 articles were included in our study, from which 8 additional references were identified. After evaluating the additional 8 articles following the same protocol, 1 article was added to the study. Thus, the 4 articles obtained were discussed throughout the present study.18, 19, 20, 21 The flowchart of the study is presented in Figure 1.

Study characteristics

The characterization and methodological quality of the included CPG and SS is summarized in Table 1.

The SS reported by Collins et al. evaluates several oral care aspects for adult ICU in-patients.18 The practice for oral care together with its evidence was evaluated by a consensus committee from the British Association of Critical Care Nurses (BACCN). The assessment has been performed intending to improve the existing practices and protocols. Different factors, allowing to classify the quality of the recommendations as high and low, were established. In the study, in section ‘Findings’, 6 main recommendations are presented, i.e., the assessment and frequency of oral care, toothbrushing, oral care techniques and equipment, oral cleansing solution, toothpaste, and the technique for cleaning dentures.18

Guidelines for oral care and mouth hygiene for in-patients in pediatric intensive care units (PICU) were developed in a study by Johnstone et al.19 The guidelines were proposed based on the evaluation of 14 articles of relevance, discussing oral care specifically in this pediatric population. The evidence used for the recommendation design shows that there exists a tight and direct relationship between poor oral hygiene and the increment of plaque, bacteria colonization and a high risk of developing nosocomial infections. Therefore, it is strongly emphasized that children in PICU require getting their mouths regularly cleaned and examined. The researchers promoted informal discussions with the nurses seeking to enhance the oral health standard for children in PICU.19

The SS presented by Sedgwick et al. comprised the set of recommendations reported by the U.S. Institute for Healthcare Improvement, extended by incorporating, among many other factors, some oral care protocols.20 The added oral care procedures were designed in cooperation with respiratory therapists. In fact, although the users of the recommendations were ICU nurses, the responsibility for oral care was impartially distributed among both respiratory therapists and nurses.20 The previously mentioned cooperation reveals the need of taking into consideration multiple health disciplines in the ICU team.

Vollman et al. in their SS discussed the practices intended to provide oral hygiene and prevent oral trauma, including other aspects of the oral cavity.21 These practices are oriented to ventilated and non-ventilated in-patients. This SS also presents the necessary knowledge for users and a detailed checklist of the required tools and equipment. Also, it proposes to involve non-ventilated patients and relatives in the procedures, providing useful information related to the recommendations.21

Results of individual studies

The CPG and SS were evaluated following the quality instrument AGREE-II, as presented in Table 1. A comparative diagram is shown in Figure 2.

The SS by Collins et al. was assessed as having a high quality (100%).18 The main limitation detected referred to the dimension corresponding to ‘stakeholder involvement’ (28%), showing that the population preferences were not taken into consideration in the development of the guidelines. Additionally, regarding the dimension corresponding to ‘applicability’ (42%), there is a lack of methods and strategies to make the implementation of recommendations easier. Nevertheless, regarding the dimension ‘clarity of presentation’ (100%), the recommendations are specific and non-ambiguous. Thus, one can find details concerning duration, tools and frequencies for the practices, in addition to a classification according to the population health status, i.e., ventilated and non-ventilated patients.18

The quality of the SS by Johnstone et al. was medium (50%).19 The main strengths appeared in the 4th domain, corresponding to ‘clarity of presentation’ (100%), given that a flowchart diagram clearly shows, and in a specific manner, the practices to be followed according to children age subgroups, indicating times, frequencies and tools. On the other hand, the main limitation was identified in the 5th domain, corresponding to ‘applicability’ (8%). The SS does not present strategies to make the implementation accessible and easier nor does it discuss the possible obstacles that could interfere with the implementation. Additionally, advised or required resources to implement the recommendations are not presented.19

The quality of the SS by Sedwick et al. was determined to be medium (50%).20 According to the evaluation results, the main limitation was detected in the 3rd domain, corresponding to ‘rigor of development’ (31%). Neither the search strategy nor systematic methods are presented for the evidence. On the other hand, the 1st domain is outstanding (89%), describing in detail the objective of the guidelines, the problem question and the population. Similarly, the 4th domain (83%), with the recommendations being precise and non-ambiguous.20

The SS presented by Vollman et al. obtained scores showing a low quality (33%).21 The main limitations were found in the domains number 2 (6%) and 6 (0%), corresponding to ‘stakeholder involvement’ and ‘editorial independence’, respectively. These low scores occurred, since the development team is not clearly mentioned, the preferences of the population were not considered in the development of the recommendations and the users of the guidelines are not presented. In contrast, the 4th domain, corresponding to the ‘clarity of presentation’ (78%), becomes the main strength of this SS given that the recommendations are presented in a very clear way, including step-by-step instructions, and avoiding ambiguity.21

Results of synthesis

The 4 included SS present a total of 13 recommendations, which are related to ICU in-patients’ oral health (Table 2, Figure 3).

The mean global scores in the ideal and local scenarios in the study by Collins et al., according to the AGREE-REX tool, were 59.3% and 40.7%, respectively, showing few weaknesses in the recommendations.18 In the ideal scenario, the low score is mainly observed in the domain of ‘values and preferences’ (45.8%). since neither the objective users nor the patients’ acceptability were considered within the recommendation design. Regarding the local scenario, the main weaknesses were identified in the domains ‘values and preferences’ (15.0%) and ‘implementability’ (41.6%). As part of the recommendations, professional team training is suggested, which necessarily implies the assignment of funds, making it difficult to implement in the local context. It is well known that there are several other priorities in the local healthcare system to assign resources. The strengths for the ideal scenario were identified in the domains ‘clinical applicability’ (72.2%) and ‘implementability’ (66.6%), highlighting the fact that the recommendations are exact and explained step by step, defining the population and the health issue it intends to solve. In the local scenario, the ‘clinical applicability’ got a score of 61.0% given that the recommendations are within the nurses’ scope.18

The mean AGREE-REX scores for both the ideal and local scenarios in the study by Johnstone et al. showed a low value (approx. 16%) in the domain ‘values and preferences’ for both scenarios.19 This low score is mainly related to the fact that the preferences of the population, users and patients, were not included in the SS. The main strength for the 2 scenarios (ideal and local) is focused in the ‘implementability’ domain (approx. 67%), with the alignment between the recommendations and the SS objective clear set, i.e., to improve the oral health of in-patient children in PICU. Moreover, the resources required for the implementation of the recommendations are considered, and the SS also establishes the training and knowledge needed by the users. Although the knowledge and training requirements can become a limitation due to the lack of personnel and equipment in some regions, the recommendations are equally aligned with the oral health objectives in the local context.19

For the SS reported by Sedwick et al., the mean global scores for the ideal and local scenarios, according to the tool AGREE-REX, were low, with values of 37.0% and 29.6%, respectively.20 The main strength in the ideal context (the ‘implementability’ domain with 58.3%) is due to the impact of the recommendations on the patients’ outcomes. Moreover, professional team training is shown in detail, including the cost reduction that hospitals would achieve. Concerning the local scenario, the highest score was observed in the ‘clinical applicability’ domain (44.4%) given that the evidence used for the development of the recommendations could also be found. Nevertheless, it is quite relevant to point out that it is not feasible to perform oral care every 2 h in the local context due to the lack of personnel in ICU. The domain with the lowest score was the one related to ‘values and preferences’ for both scenarios (ideal scenario – 20.8%, local scenario – 12.5%).20

The AGREE-REX scores for the SS presented by Vollman et al. showed a medium quality, with a value of 44.4% in the ideal scenario and 39.7% in the local scenario.21 This SS has an impact on the users, as it stipulates the pre-requisite knowledge. Also, this SS mentions the suggested education schemes for both patients and their relatives, which can end up in the successful dissemination of the recommendations. In addition, they can be customized for patients form different subgroups. The latter justifies the highest score observed in the domain known as ‘implementability’ (75.0%). In the same way as discussed above for Sedwick et al., the SS by Vollman et al. has the main weaknesses in the domain of ‘values and preferences, for the ideal and local scenarios, with a value around 4%. Although the SS involves the nurses by mentioning their pre-requisite knowledge, and the patients by suggesting education schemes, the values and preferences of these objective users and the population were not reported in the design of the recommendations.21

Discussion

Given that in-patients in ICU are in a critical health state that puts their life in danger, oral care is not part of the priorities. The oral issues are shadowed and underestimated because of other health complications concerning other integral health fields,20 which might explain the lack of previous studies on the CPG and SS concerning this topic. To the best of our knowledge, the quality assessment of SS related to the oral health of ICU in-patients, as well as their recommendations, has not been reported in the literature yet.

The previously mentioned situation suggests a new problem. In cases where the in-patient overcomes their health difficulty and is discharged from ICU, they will have to deal with oral health issues in the long term, as during their stay in hospital, they could develop caries, gingivitis and periodontitis, among others.22, 23 However, within the assessed SS, one can find several practices involving oral care, which can, in turn, be complemented and improved to mitigate future oral health issues in ICU in-patients.24

The identified quality of the 13 recommendations found, related to oral care in ICU in-patients, was low. With regard to the SS objective, recommendations that are exclusively oriented to the prevention of oral health issues were not found. However, there were recommendations linked with oral care, but mainly intended to prevent ventilation-associated pneumonia (VAP).25

Additionally, the proposed recommendations lack of a rigorous methodological design, e.g., the different considerations depending on the population comorbidities, the alignment between the practice scope and the objective users’ actions to achieve a proper clinical applicability, the identification of the required resources, and the detection of possible barriers. Given that the aforementioned elements are missing, the implementation of the recommendations turns to be difficult.

Four possible roles, which oral health professionals can either directly or indirectly play in the oral care of ICU in-patients, have been determined.23 First, the participation of the dentist in the design of the recommendations. The existence of some SS, which already have recommendations associated with oral care to avoid the development of respiratory infections, becomes an opportunity to complement such recommendations by considering possible oral complications. Second, the dentist actively executing the recommendations, i.e., the dentist being part of the ICU team. Some evidence has shown improvement in oral health and the prevention of respiratory infections when involving the dentist.23 Third, the dentist performing the training of the CPG and SS users. For example, the nurses have been shown to perceive the ICU in-patients’ oral care as the most difficult task to do, in addition being a low-priority intervention.21 Thus, there is an undoubtable need for the ICU nurses to be trained by the dentist. Fourth, the dentist in the post-ICU care. Most of the patients who get discharged from ICU have to deal with health sequelae at the physical and mental level, known as post-ICU syndrome.26 It is required to evaluate whether the knowledge-based and practice-based training of the dentists is adequate to cope with the challenges emerging during the post-ICU period.

Limitations

Some limitations must be considered. Since it is a systematic review, one should keep in mind the existing bias caused by the language, which was constrained to English and Spanish. Therefore, gray literature reports could have been omitted within the systematic review.

Conclusions

There exists a high risk to develop oral health complications in patients after having been discharged from ICU, even though oral care-related recommendations were followed. Oral care recommendations are not designed to prevent oral complications; instead, they are designed to prevent respiratory infections associated to ventilation.

This shortcoming presents an opportunity to complement the existing recommendations, broadening their purpose – not only focusing on infection prevention, but also on mitigating the potential long-term oral complications during the post-ICU period. It is concluded that the dentist plays a significant and essential role in improving CPG and SS for ICU in-patients. Additionally, it is crucial to consider the management and economic limitations, as well as the coverage of the health care system, when implementing these recommendations in the local context.

Registration and protocol

The present study is registered in PROSPERO under the ID CRD42021254982. It follows a rigorous methodology proposed by Johnston et al.,13 and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.27

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.