Abstract

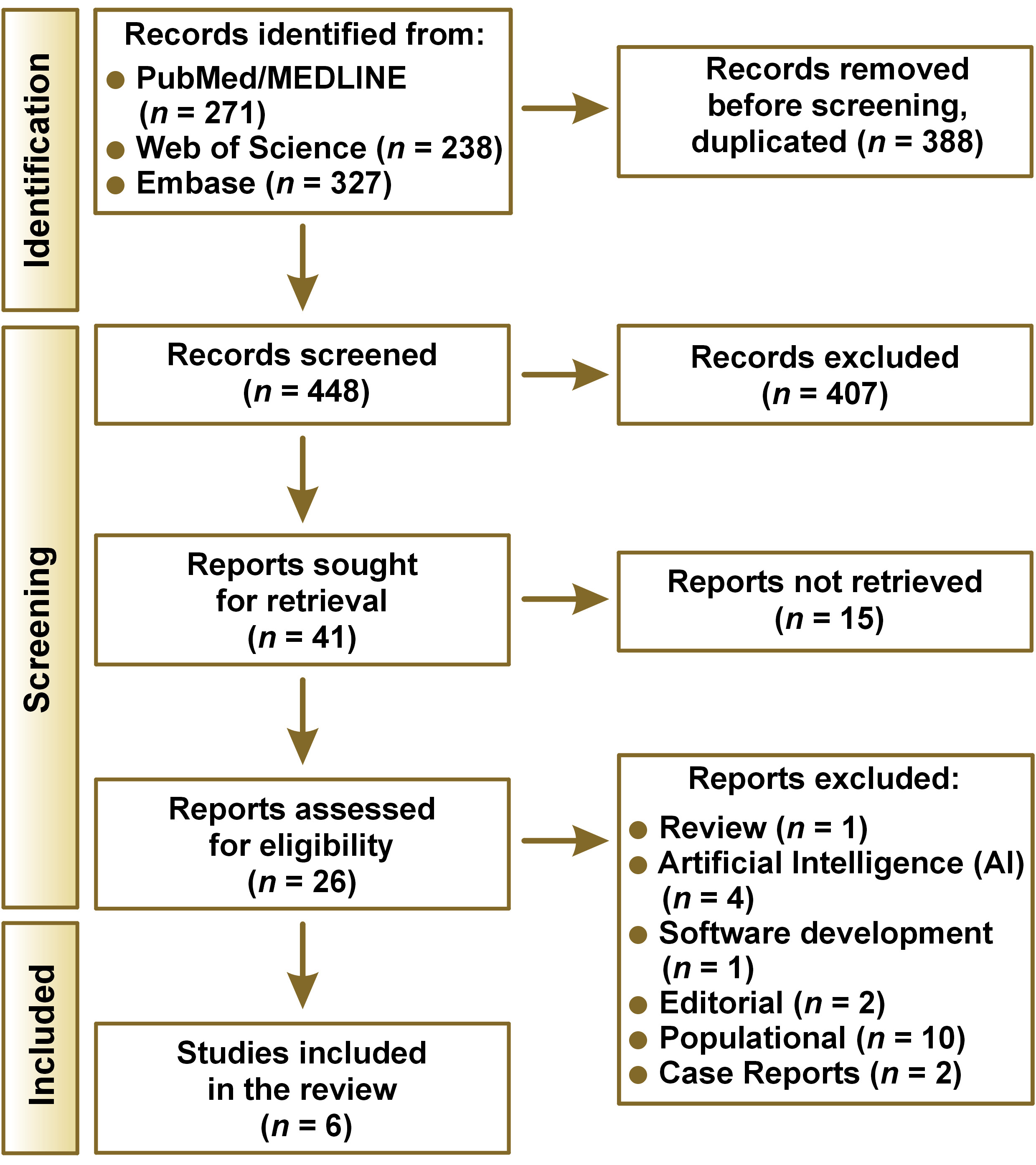

This critical review revisited the new classification system for periodontitis, specifically for staging, suggesting modifications and introducing a new flowchart for a better clinical evaluation. It evaluated articles published between 2018 and 2024 in the English language, which had an educational motivation focused on staging periodontitis. The PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science and Embase databases were used to retrieve the articles. The focus questions involved the analysis of all parameters for staging periodontitis.

A total of 836 articles were initially found, of which 388 duplicates were excluded, 448 were evaluated by title and abstract, 26 articles were followed for full-text reading, and 6 articles were finally included in this critical review (k = 0.98). All articles included detailed parameters and steps referring to diagnosing periodontitis. Therefore, it was possible to observe instability and ‘gray zones’ in the staging step, which was due to the lack of priority and an organized order sequence.

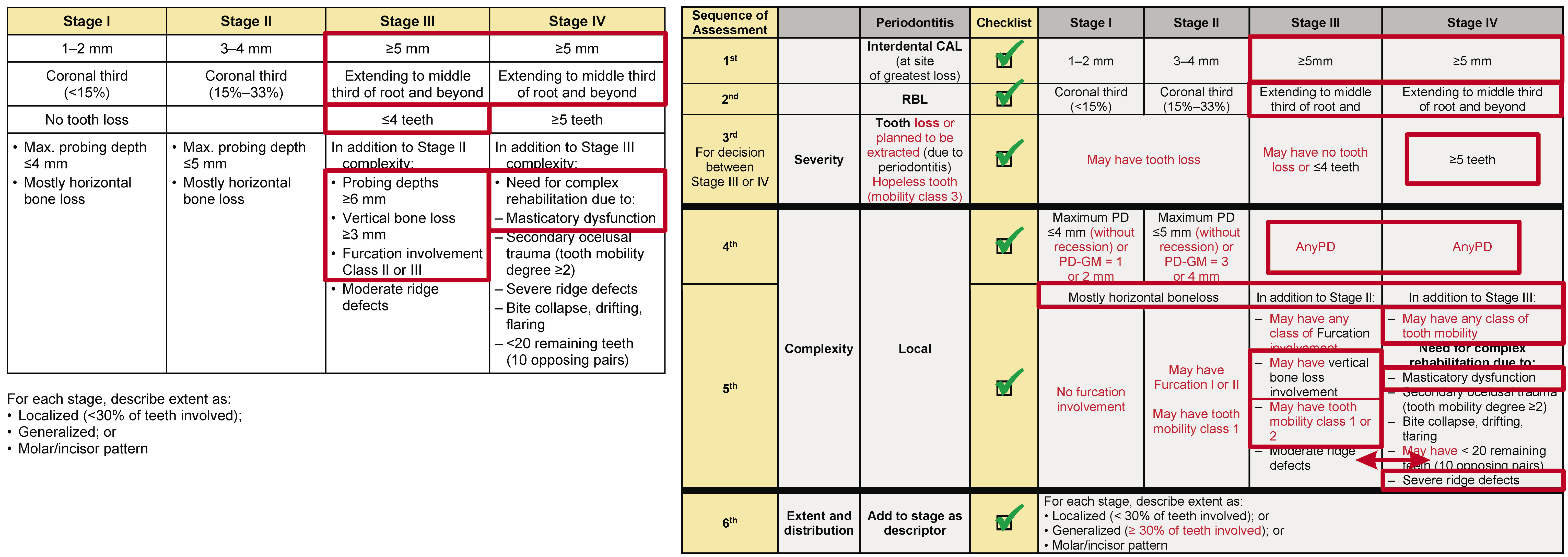

This review suggests the severity parameters cannot be overcome by the complexity parameters, following a cumulative sequence: clinical attachment loss (CAL) (1st); radiographic bone loss (RBL) (2nd); tooth loss due to periodontitis (TLP) (3rd); and then the complexity parameters. An exception must be permitted only for the complexity factors between Stages III and IV that can change the initial Stage (III or IV) obtained through the severity analysis, but only between the 2 stages. Moreover, for patients without tooth loss or with TLP ≤ 4 (without the need for complex rehabilitation), and presenting any type of drifting or flaring or a secondary traumatic occlusion, there is no justification for moving the diagnosis from Stage III to Stage IV.

Keywords: periodontitis, diagnosis, classification, review

Introduction

Periodontitis is a plaque-induced multifactorial disease (dysbiosis) with a chronic inflammatory nature, characterized by microbially associated and host-mediated (determined by genetic, epigenetic, lifestyle, environmental, and behavioral risk factors), which is characterized by progressive destruction of structures that support the tooth, such as local bone and periodontal ligament; ultimately, at a more severe level, can cause tooth loss.1, 2 It may compromise and affect mastication, esthetics, self-confidence, and quality of life.3 Periodontitis was listed as the 11th most prevalent condition in the world.4 Moreover, it is known that periodontitis shares risk factors with other chronic diseases5, 6, 7 and has bidirectional associations with general health.8 This fact leads the clinical and scientific community to the consensus that improvements in the periodontal condition may offer benefits for systemic health and well-being.2 Similar to many other chronic diseases, periodontitis has no cure. Then, it is paramount to do supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) (“periodontal maintenance”) to prevent the progression because it is not possible to eliminate the disease and future complications.9 For this reason, patient-risk assessment must be performed at multiple levels (patient/systemic level, mouth level, tooth, and site level).10 The concept of risk assessment was implemented in the new Classification system for periodontal diseases.11

This new Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions, published in 2018, is one of the most complete classifications for periodontal and peri-implant diseases.12 It was developed from the efforts of the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) at the 2017 World Workshop. This new classification system, worldly disseminated, created a periodontitis group divided into (1) periodontitis, (2) necrotizing periodontitis, and (3) periodontitis as a result of the systemic condition. Then, Periodontitis includes staging and grading dimensions, requiring attention for many clinical parameters and radiographic examinations.13

The staging and grading system brings multiple levels of evaluation to help with the classification of periodontitis and to distinguish approaches to manage clinical cases better.11 Staging aims to evaluate the severity based on the interdental clinical attachment loss (CAL) at the site of greatest loss, radiographic bone loss (RBL), tooth loss due to periodontitis; the complexity of treatment, which observes probing depth (PD), bone loss pattern (horizontal/vertical), furcation involvement, ridge defects, and the need for complex rehabilitation due to masticatory dysfunction, secondary occlusal trauma, bite collapse, drifting, or flaring; and extent and distribution of periodontitis, localized (< 30% teeth), generalized (≥ 30% teeth), or molar-incisor distribution. Grading has added another dimension and aims to determine the rate of disease progression and the response to standard periodontal therapy through RBL or CAL over 5 years, the percentage of bone loss/age, and the presence of specific risk factors (diabetes and/or smoking).13

The dentistry community is still undergoing the process of adaptation to this new system. Some “gray zone” cases have appeared for treatment, which may produce uncertain clinical scenarios.14 Thereby, students, clinicians, specialists, researchers, and educators have had general difficulties adopting, understanding, teaching, and applying this new classification in the routine. The complaints turn around the difficulties in determining the stage and grade of periodontitis due to the existence of many clinical and radiographic parameters.15 To overcome these problems, some strategic flowcharts have been published. They were considered a simple way to make decisions. They were proposed not only to facilitate the performance of fast and accurate periodontitis staging and grading but also to minimize confusion and inconsistent diagnoses.15, 16, 17 However, they raised questions and concerns regarding some points, e.g., considering “tooth loss” as the primary criterion for the severity of periodontitis.

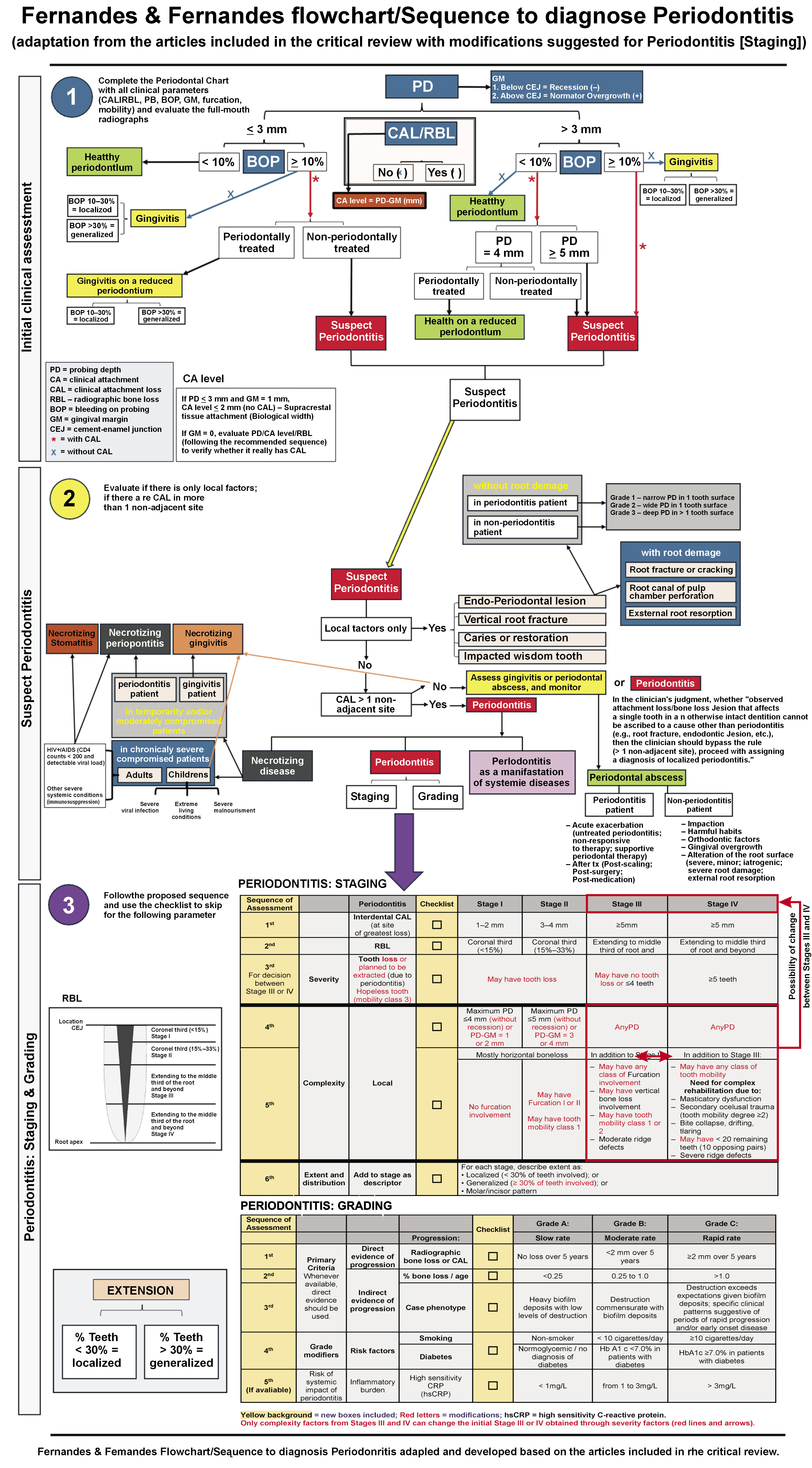

Therefore, many questions commonly appear similar to the implementation of any new system. However, professionals must continue applying this new classification in their routines in order to become more familiar with it. Even with this, the correct assessment of the stage and grade for periodontitis has raised a high level of concern since it is not practical for many clinicians to find and make rapid diagnoses in daily practice.13, 18, 19 Then, the goal of this critical review was to revisit the new classification, specifically regarding the staging of Periodontitis, in order to clarify and discuss specific points, suggest some modifications, and introduce a new flowchart for a better clinical evaluation of the periodontitis.

Methods

This critical review evaluated the articles published after the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions, which had an educational motivation to clarify the new classification focused on periodontitis. The strategy used to obtain the articles involved the keywords combined with Boolean operators: “Periodontitis,” OR “Periodontal,” AND “Classification,” AND “Diagnosis,” and (NOT “Treatment”). The strategy varied depending on the database, PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Embase (Table 1). The focus questions of this review were: (1) “Are all parameters to evaluate periodontitis clearly exposed and explained?”; (2) “Could tooth loss be considered a more important parameter than CAL and RBL to define the severity of the Stage of Periodontitis?”; (3) For the complexity of the case with Periodontitis, are the parameters really well-established to accurately guide the professionals and clinicians to achieve the periodontal diagnosis?

Eligibility criteria

For inclusion, it was considered all articles published from January 2018 to May 2024 in the English language presenting an educational and instructive approach to the new classification for Periodontitis regarding Stage, specifically, severity and complexity. It excluded any article published that reported only gingivitis or peri-implantitis or had the focus on Grade, or systemic condition correlated to periodontitis; articles that had a primary focus on materials or other substances used in patients diagnosed with periodontitis; populational studies observing the prevalence or incidence of periodontitis; studies evaluating results of professionals and/or students using the new classification; case reports, case series, preprints, chapters, books; any article evaluating periodontal patients who received implant placement; articles that used artificial intelligence (AI) for assessment or development of tools/applications/software; commentaries, opinions, poster in congress, editorial letter or letter to the editor; animal or in vitro studies; and any type of review; same article (duplicated) published in more than one journal.

Study selection

The studies retrieved from the electronic search were screened by two authors (G.F. and J.F.); duplicated studies were excluded. After removing duplicate records, the initial study selection based on title and abstract was performed by the same two assessors who independently screened the articles considering the eligibility criteria. A meeting and discussion resolved disagreements between the two evaluators. The full text of the selected articles and the studies with unclear abstracts was retrieved, and the inclusion in the review was decided by consensus of the two reviewers. Cohen’s kappa was performed to evaluate the degree of accuracy and reliability between assessors (inter-agreement level).

Data retrieved

Data collection from the selected studies was performed using a standardized spreadsheet on Excel software (v.16.86, Microsoft Office Excel, 2024). For each included article, the information retrieved included the authors, title, journal name in which the article was published, journal’s impact factor (IF), objective, how staging of periodontitis was evaluated, and specific educational details such as flowcharts.

Results

A total of 836 articles were initially found. Three hundred and eighty-eight duplicated articles were excluded. Only 26 articles followed for full-text reading. Then, 6 articles11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 were included in this critical review. The justification for the exclusions and all screening processes is summarized in Figure 1. There was a high agreement between the assessors (k = 0.98).

In this critical review, 6 articles were included with the presence of 40 authors. The percentual of the authors per country was: Australia (2.4%), China (2.4%), Germany (4.9%), Hong Kong (4.9%), Israel (2.4 %), Italy (2.4%), Spain (4.9%), Switzerland (4.9%), Thailand (4.9%), the Netherlands (2.4%), Turkey (2.4%), the U.K. (24.4%), and the U.S.A. (36.6%). The authors with more participation in the articles included were: Kornman KS (3), Tonetti MS (3), Dietrich T (2), Greenwell H (2), Needleman I (2), Papapanou PN (2), Sanz M (2); the other authors, participated only once.

Current general findings for staging periodontitis based on the new classification system

Due to the measurement error of CA level using a standard periodontal probe and, sometimes, considering the inexperience of the clinician, misclassification of the initial stage of periodontitis is inevitable, thus affecting the diagnostic accuracy.13 With the disease severity progression, CAL is a more firmly established parameter, permitting the identification of periodontitis with greater accuracy.13 Then, diagnosing periodontitis initially, prior to staging and grading, should be carried out using the following criteria: the presence of (a) interdental CAL at ≥2 non-adjacent teeth; or (b) buccal/oral CAL ≥3 mm with a probing depth (PD) >3 mm at ≥2 teeth; and (c) the found CAL should not be correlated to non-periodontal causes.13

Staging pursues to determine the severity (interdental CAL at the site of greatest loss, %RBL, TLP) and extent (generalized [≥30% teeth involved], localized [<30% teeth involved], molar/incisor pattern) of periodontitis and, then, the complexity of its management (PD, bone loss pattern [horizontal/vertical], furcation involvement, ridge defects, and the need for complex rehabilitation due to masticatory dysfunction, secondary occlusal trauma, bite collapse, drifting, or flaring) based on the amount of periodontitis-induced tissue destruction and specific factors.13

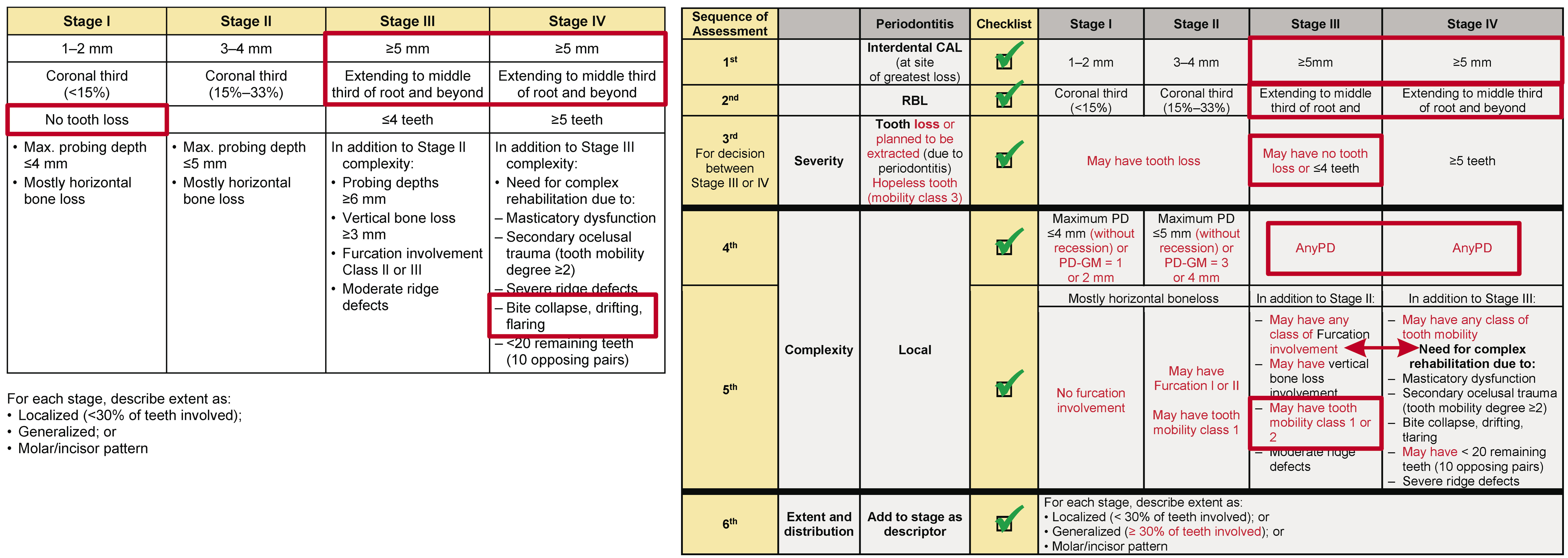

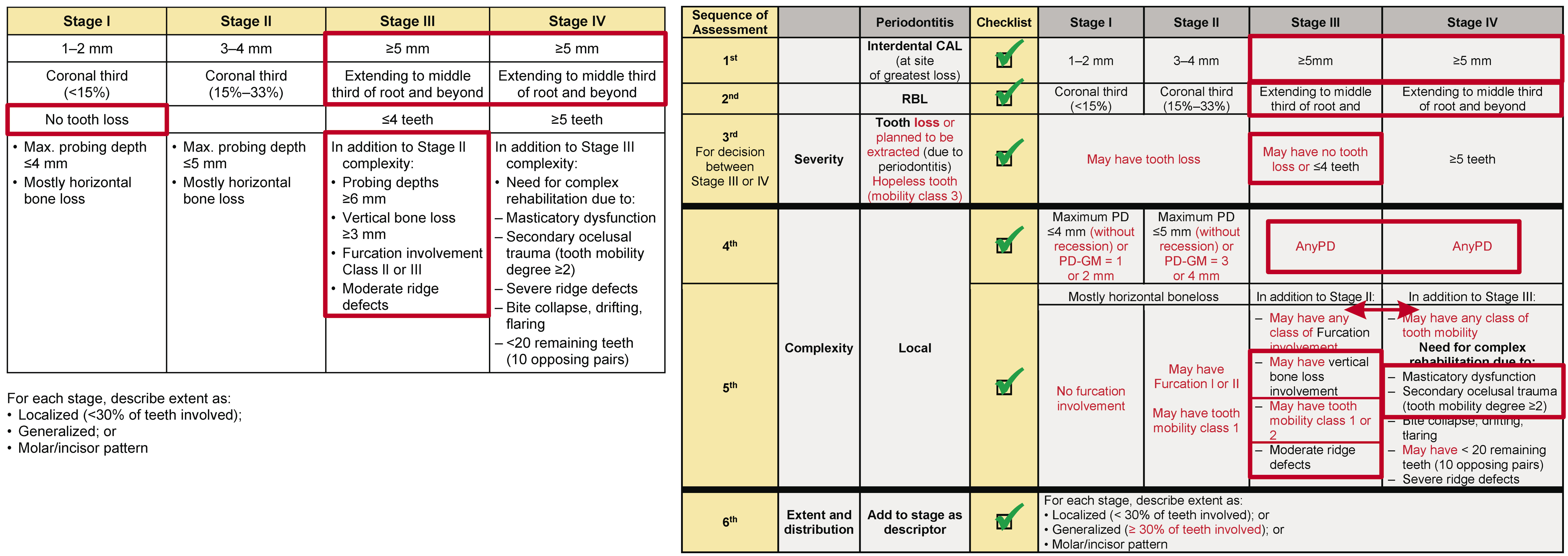

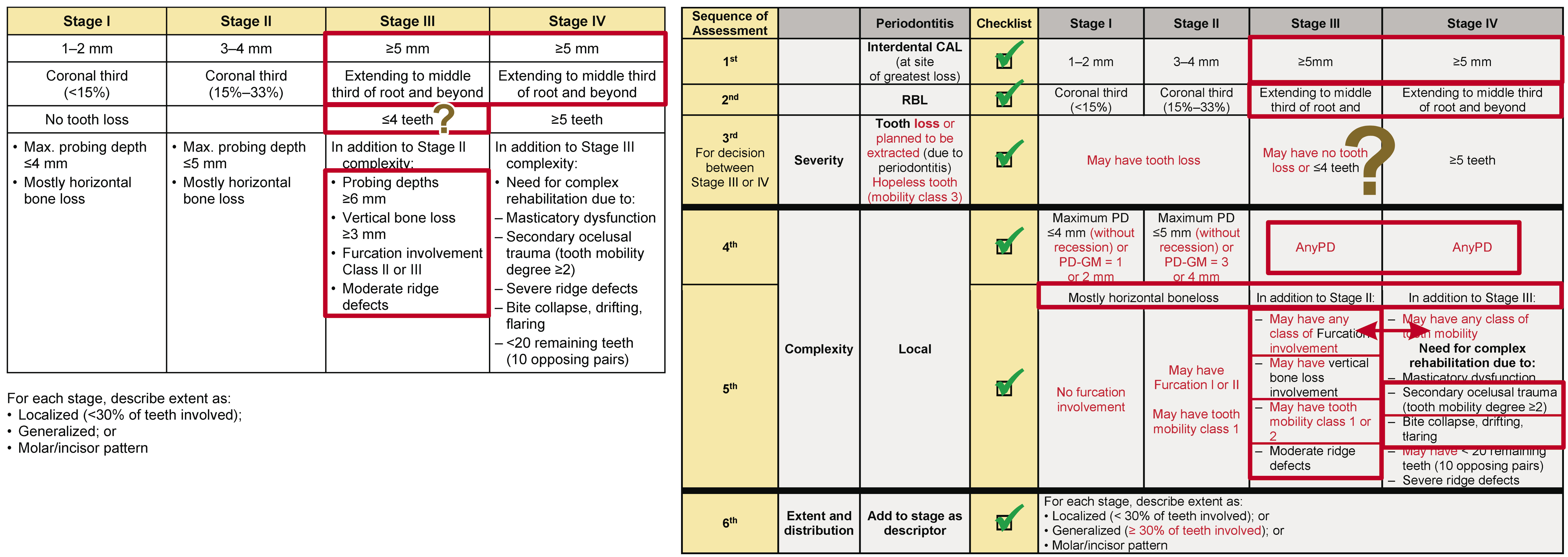

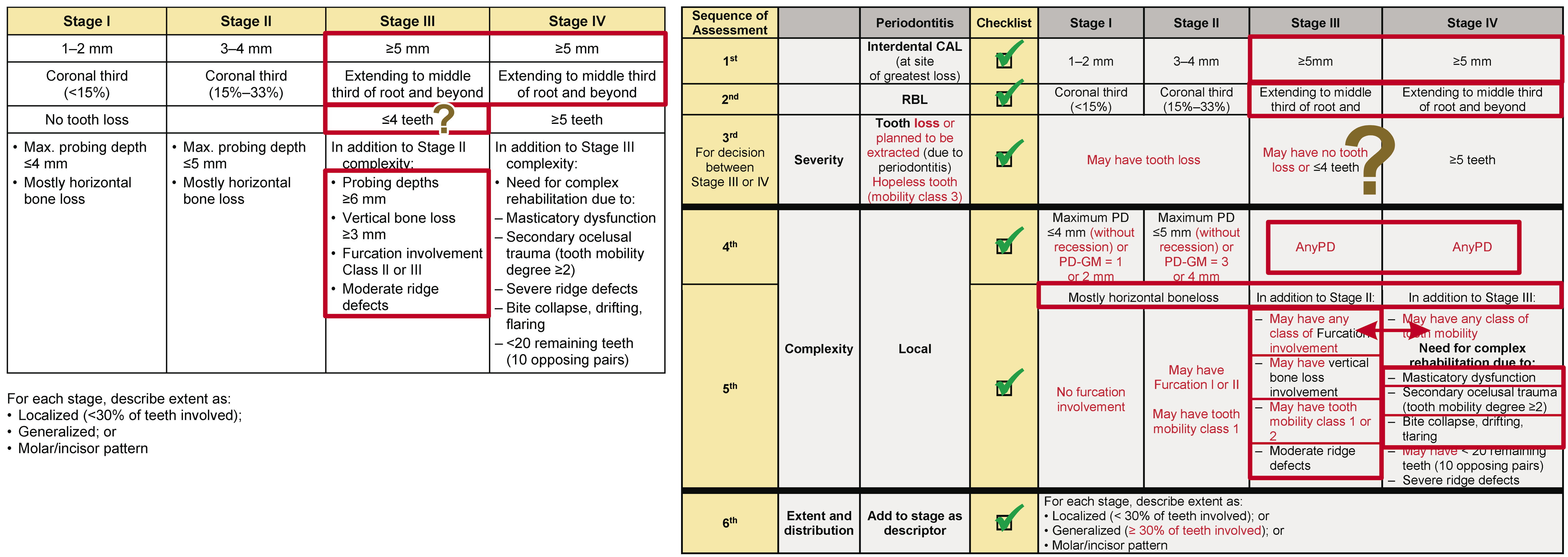

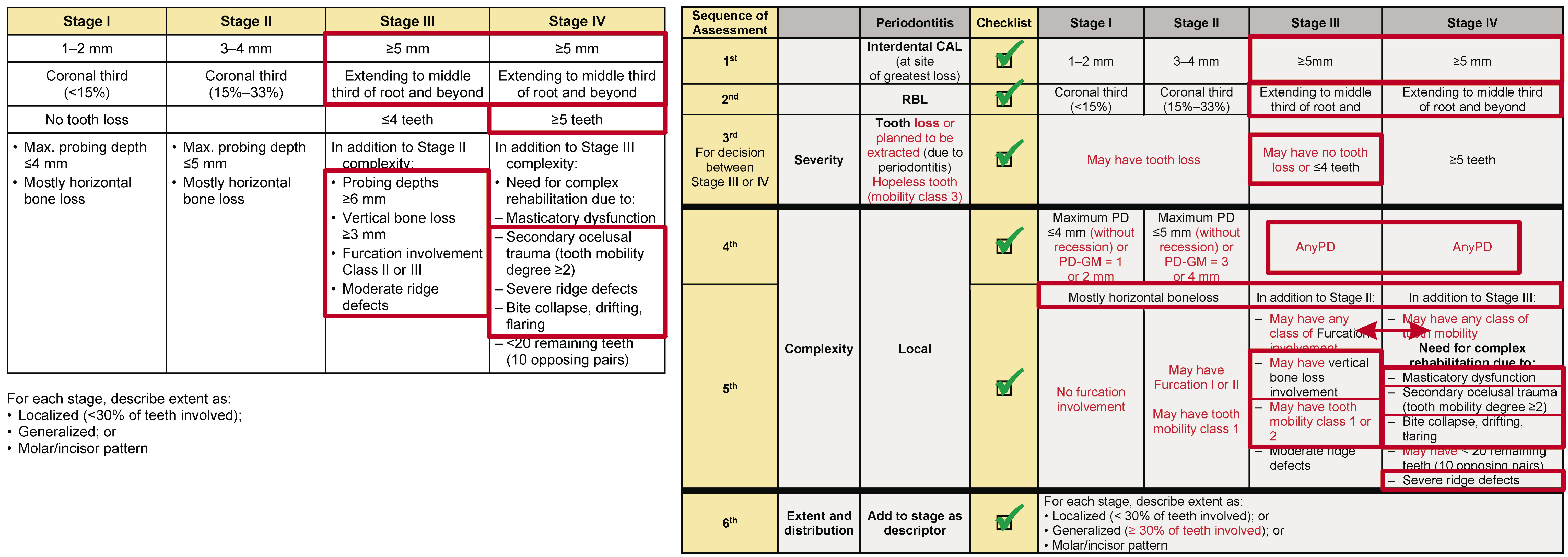

Staging can be summarized following the severity and complexity below:

Stage I: a. Severity: CAL ≤1–2 mm, RBL at the coronal third of the root (<15%), and no tooth loss due to periodontitis; b. Complexity: PD ≤4 mm, mostly horizontal bone loss.

Stage II: a. Severity: CAL between 3–4 mm, RBL at the coronal third of the root (between 15% and 33%), and no tooth loss due to periodontitis; b. Complexity: PD ≤5 mm, mostly horizontal bone loss.

Stage III: a. Severity: CAL ≥5 mm, RBL extending to the middle third of root and beyond, and loss of ≤4 teeth due to periodontitis; b. Complexity: PD ≥6 mm, horizontal bone loss, and may have vertical bone loss; may have furcation involvement of class II or III.

Stage IV: a. Severity: CAL ≥5 mm, RBL extending to the middle third of root and beyond, there is the potential for loss of ≥5 teeth due to periodontitis; b. Complexity: PD ≥6 mm, horizontal bone loss and may have vertical bone loss, may have furcation involvement of class II or III, need for complex rehabilitation (masticatory dysfunction, secondary occlusal trauma, bite collapse, drifting, flaring, severe ridge defects, <20 teeth may be present or less than 10 opposing pairs).

Summarization of the included studies

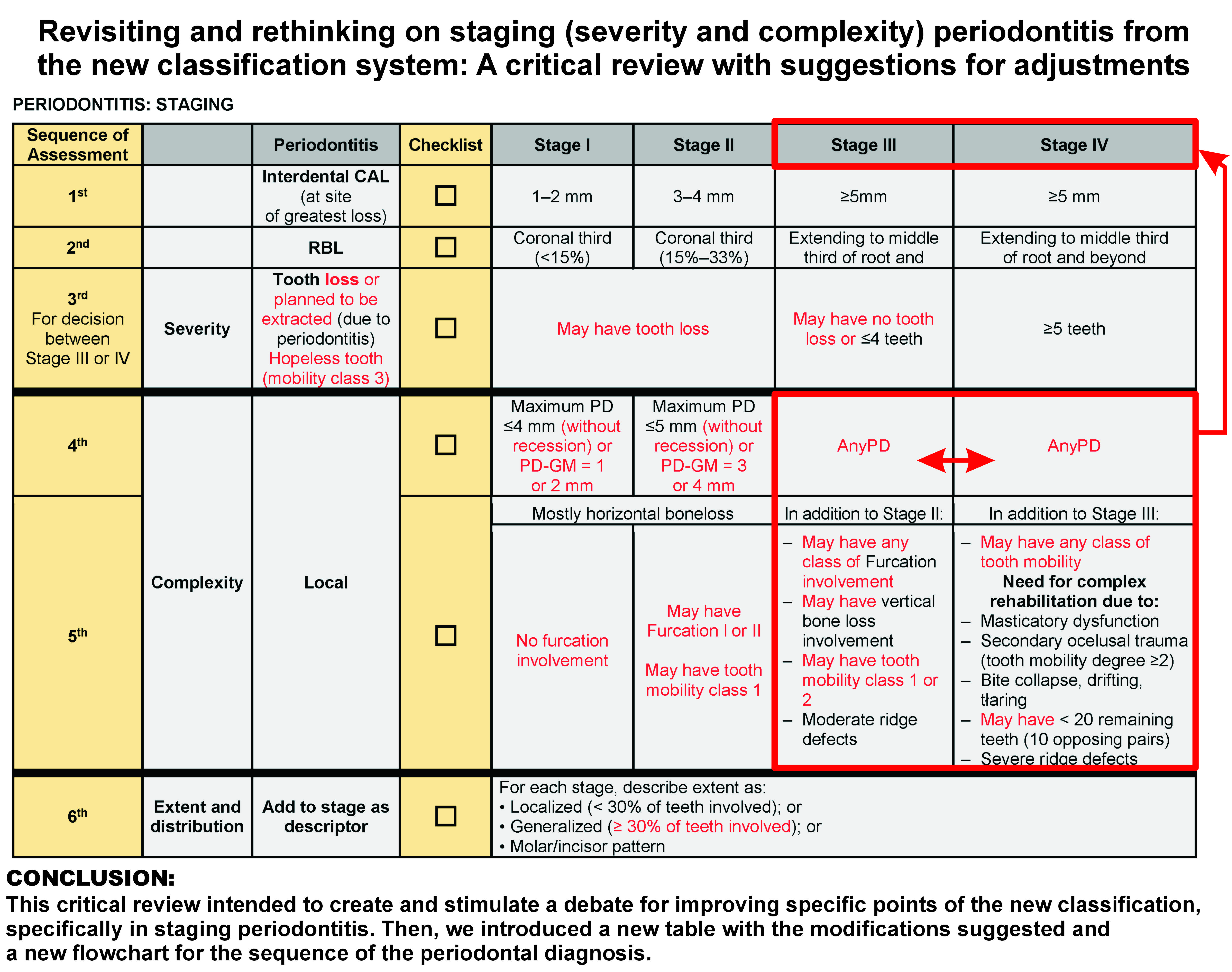

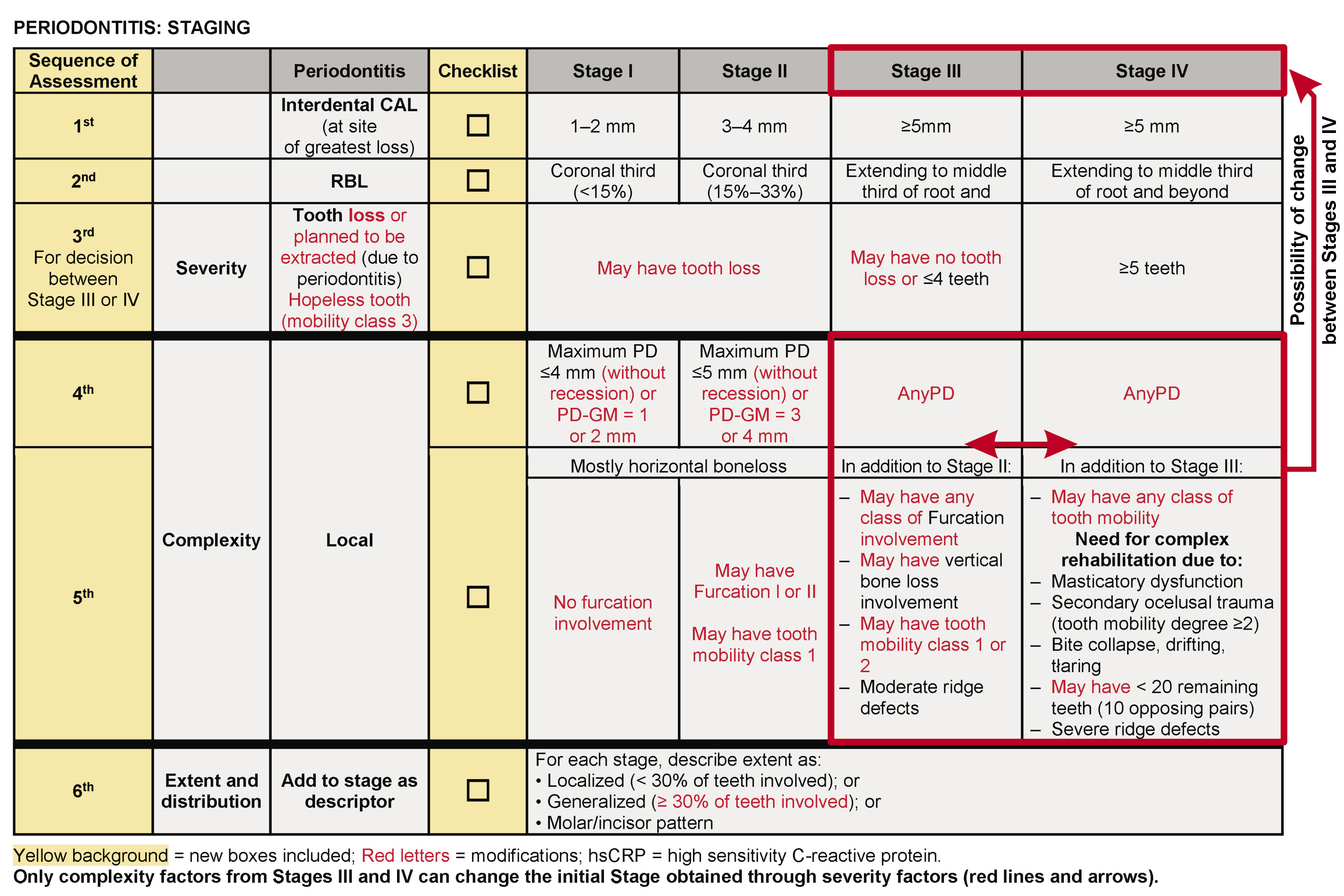

The articles included in this review were deeply analyzed, and all details were included and discussed (Table 2). Figure 2 shows all suggested modifications (for staging). The justifications and explanations for the proposed changes are discussed in the sequence.

Discussion

The new classification system for periodontitis recommends shifting the stage according to whether a stage-shifting complexity factor(s) exists. However, this methodology can create a non-real scenario of a periodontitis case. Then, this critical review strongly suggests a modification for these parameters (complexity); no one of the complexity factors should shift the stage in periodontitis and overcome the severity primarily found. The only exception is for complexity factors from Stages III and IV that can cause interchangeability for the Stages initially obtained through the severity factors (Figure 2).

In addition, the classification follows that: (a) if any complexity factor(s) is(are) eliminated by the periodontal treatment, the stage should not retrogress to a lower stage since the original stage complexity factor should always be considered in the maintenance phase management.13 This fact can permit a non-correct scenario analysis of the case. This critical review strongly suggests that if a case has the severity parameters kept stable after 12 months, a new diagnosis must be obtained (shifting downwards); (b) Therefore, if a patient has been staged before and had significant disease progression, even after periodontal therapy, resulting in increased severity and/or more complex treatment needs, in this case, the stage must be shifted upwards at the time of the subsequent examination. This review agrees with this position in order to better treat the case.

Severity: Conflicting parameters

Tooth loss due to periodontitis (TLP) as a parameter to define the stage

It is known that the initial stage of Periodontitis should be determined using CAL (as a result of Periodontitis). If CAL is not immediately available, RBL should be considered. In addition, TLP or a tooth planned to be extracted because of periodontitis currently may modify the stage definition;13 but in many scenarios, tooth loss information is not tracible or available (without the history of the patient), or it is necessary to trust in the patient’s report (there is no accuracy for the information). Hence, to work excellently, the clinician must obtain CAL (developing a new periodontal chart) and RBL and also verify the number of TLP, thus ascertaining the severity. It must be remembered that RBL needs to encompass a substantial portion of the buccal-lingual dimension before conventional radiographs can visualize it; then, the lack of readily discernible RBL does not preclude the presence of periodontitis of incipient severity; this is why the diagnosis of periodontitis is based on CAL rather than RBL.14 Moreover, the area with CAL must be in 2 non-adjacent sites between 2 teeth to be considered periodontitis.

Tooth loss is currently one of the parameters used to determine the severity of periodontitis. Nonetheless, the impact of tooth loss still needs to be clearly defined in the new classification system. Iwasaki et al.20 evaluated 374 elderly patients with 7,157 teeth enrolled. The authors registered four lifestyle factors: (1) cigarette smoking, (2) physical activity, (3) relative weight, and (4) dietary quality; scored as healthy (1 point) or unhealthy (0 points) (the least healthy=0; the highest score=4 points). After 6 years, 19.0% of the teeth (n=1,360) exhibited periodontitis incidence or progression, and 8.2% (n=567) were lost. The highest score (4 points) was associated with a significantly lower tooth-specific risk of periodontitis and tooth loss. The authors concluded that simultaneous adherence to multiple healthy lifestyle factors substantially reduces the risk of incidence or progression of periodontitis and tooth loss in older adults. Then, this parameter (TLP) could be better evaluated in the presence of an assessment that includes many other variables that may increase/influence the predictability of periodontal treatment and perspective. This fact shows that around 8% of the teeth were lost after 6 years, which means a low number of TLP and remaining questions about the reliability of using this parameter (“tooth loss”).

It is known that there exists a straight relationship between periodontitis and tooth loss. Takedachi et al.21 evaluated 607 periodontitis patients (mean age of 54.4 ± 11.9 years); 12 (2.0%) had diabetes, 43 (7.1%) were active smokers, and 93 (15.3%) were former smokers, with a mean number of teeth present of 26.1 ± 3.7 at baseline. The total duration (months) of the whole treatment period, active periodontal therapy (APT) period, and supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) period was, respectively, 80.9 ± 34.2 (range: 16 to 190 months), 11.1 ± 6.4 (range: 2 to 35 months), and 69.9 ± 35.3 (range: 12 to 174 months). 176 patients (29.0%) were classified into stage III grade C, followed by 159 (26.2%) in stage III grade B, and 128 (21.1%) in stage II grade B. During the treatment period, 260 teeth (63 during APT and 197 during SPT) out of 15,838 were lost (1.64%). They reported that patients in stages I and II (grades A, B, or C) had no TLP during the treatment period. Patients in stage IV and grade C had TLP rates of 0.24±0.31 and 0.15±0.24 (number of teeth/patient/year), respectively, with significant differences from those in the other stages and grades. TLP rates were higher in stage IV and/or grade C patients during both APT and SPT. Multivariate analysis revealed that stage IV and grade C as independent variables were significantly associated with the number of instances of TLP not only during the total treatment period and also during APT or SPT. The results of this study suggested that the new classification has a significantly strong association with TLP during both APT and SPT and that patients diagnosed with stage IV and/or grade C periodontitis had a higher risk of TLP during both periods. Thus, it was possible to observe that TLP was totally correlated to stages III and IV; this fact led us to understand that this parameter is highly important only in deciding the severity of those stages (III or IV) (Figure 2). Moreover, if the patient is qualified for Stage III or IV (CAL ≥5mm and RBL extending to the middle third of the root and beyond), therefore, without any TLP or tooth due to another reason, the patient must be framed in Stage III. This critical review suggests that “May have no tooth loss” for Stage III (Figure 2).

Even without precision regarding the impact of TLP on periodontitis, some authors16 reported that this parameter should be considered the most important in defining the severity of periodontitis, compared to CAL and RBL. They considered tooth loss the first criterion of analysis for staging Periodontitis, ignoring the new classification recommended as primary criteria CAL and RBL. It was described in their article, “In the flowchart for periodontal stage, information of TLP was selected as the first criteria to separate patients with severe periodontal conditions, which can be stage III or IV”. Even though it can be a good strategy and a shortcut to sift patients, it can lead to mistakes. Also, the authors included that “in the case that periodontitis is diagnosed from the flowchart but with no obvious RBL/CAL, clinicians must confirm the diagnosis again, considering the periodontitis case definition”; hence, without obvious CAL/RBL (which were not measured), it is necessary to redo the periodontal assessment.

Then, a question is posed: What is the reliability of this criterion (TLP) as the first evaluation parameter? In some cases, the patient needs to be informed of the reason for the extraction because the professional does not have a history of previous treatments. Moreover, the authors affirm this criterion is enough to find patients with severe periodontitis; again, it can be an interesting strategy; nevertheless, it does not follow the concepts proposed by the new classification system, which recommended CAL and RBL for the initial assessment and can generate a non-precise result.

Therefore, screening patients considering TLP as the primary deciding factor for staging the severity of Periodontitis is not suggested. This information may lead clinicians to misunderstand, misinterpret, and possibly make mistakes in finding the severity and stage, which are extremely necessary to define the periodontal diagnosis and treatment plan. Moreover, due to this type of approach worldwide, many educators, students, and professionals are using the concept of “TLP” as the primary criterion for the severity of periodontitis, completely disregarding CAL and RBL. Additionally, this approach completely overlooks specific cases that can justify its non-application, such as teeth loss posed by the former localized aggressive periodontitis (periodontal disease with rapid progression) (example 1) or in the case of complete maxillary teeth extractions for rehabilitation without a periodontal reason, resulting in less than 10 opposing teeth pairs (example 2).

Example 1: Latin male patient (22 years old) with 26 remaining teeth (without wisdom teeth). Only one of them, 2nd premolar [ADA #20 or FDI #35], with CAL in the mesial (PD = 5mm; CAL = 2mm) and distal (PD = 5mm; CAL = 2mm); the other two teeth were lost due to periodontitis (central incisor [ADA #9 or FDI #21] and 1st molar [ADA #19 or FDI #36]), without any other tooth being affected by periodontal issues. Observing the current scenario, with 2 teeth lost to periodontitis and only 1 remaining tooth with periodontitis, the patient was diagnosed with Localized Periodontitis Stage III (former Localized Aggressive Periodontitis – a periodontal disease with rapid progression). Therefore, it does not make sense to consider Stage III because of the number of teeth lost, not considering the CAL and RBL. In addition, typically, periodontitis is treated with scaling and root planning (SRP) procedure; however, where could it be used to treat the case demonstrated in example 1? Possibly only on tooth #20/#35. This fact (Stage III) does not agree with the actual severity of the periodontal disease found, recommending a more accurate diagnosis, resulting in Localized Periodontitis Stage I, after ascertaining the CAL.

Example 2: Patient, female (50 years old) with a long history of caries and periodontal disease. She arrived for evaluation with an edentulous maxilla without any wisdom teeth and 11 lower remnant teeth. Two of them, posteriors, were planned to be extracted due to decay. The PD found was 2-3mm for all the present teeth with a general GM of 1mm (normal position [1mm coronally CEJ]); no CAL or RBL was observed. Then, the clinical assessment resulted in less than 10 opposing teeth pairs and undefinition for the reason of other extractions. If followed the suggestion of the flowchart above, this fact led to the direct diagnosis of Periodontitis Stage IV (<10 opposing pairs and complex rehabilitation). Therefore, to treat the most severe level of periodontitis (Stage IV), it is usually necessary to make appointments for SRP. But where should we apply SRP in this case? It does not fit for this scenario. Observing the remaining teeth, this case could be considered Periodontal Health or, depending on the BOP result, gingivitis, based on CAL and RBL present (without previous history).

The suggestion of this critical review is to remove “no tooth loss due to periodontitis” from the official recommendation for Stages I and II, which may have or may not have TLP, and keep this parameter only for differentiation between Stages III (it may not have TLP) and IV (Figure 2), but after assessing CAL and RBL. This fact will permit the clinicians not to consider first TLP (involving periodontally hopeless tooth, which means irrational to treat - where the CAL approximates the apex of the root circumferentially, in combination with a high degree of tooth hypermobility, degree III),22 reaching a more accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, remembering that the 1st and 2nd analysis parameters are CAL and RBL, which depend on the PD and GM position is worth remembering. All of them must be acquired before evaluating the number of tooth losses to define the stage of periodontitis.

Thus, summarizing the assessment of severity for periodontitis, this critical review suggests and strongly recommends checking the parameters cumulatively, following the sequence: 1st – CAL (with PD and GM); 2nd – RBL; 3rd – tooth loss (for decision between Stages III and IV) (Figure 2). It is also important to highlight that if the patient has TLP (3 teeth), but the worst site CAL is 4mm, the Stage must be kept on Stage II, respecting the cumulative sequence suggested (Figure 2).

Complexity

In the new classification system,13 the authors recommended: “Complexity factors may shift the stage to a higher level”. Besides CAL, RBL, or TLP (severity factors), the role and relative importance of the complexity factors of periodontitis in defining the stage cannot be justified only by PDs, furcation status, tooth mobility, type of bone loss, the extent of ridge defect, masticatory dysfunction, and missing teeth or a number of opposing pairs as proposed by the classification. Thus, this review strongly suggests an adjustment for the above affirmation that considers the complexity factors sometimes more relevant than the severity factors. The suggestion for modification is that never one complexity parameter can overcome a severity parameter, changing the initial Stage obtained following CAL (1st), RBL (2nd), and TLP (3rd). An exception must be respected only for complexity factors between Stages III and IV that can change the initial Stage III or IV obtained, only between themselves, according to the complexity found in the case (Figure 2).

Furcation

The mean root trunk lengths (RTL) reported when vertically assessed (from cementoenamel junction [CEJ] to furcation) in maxillary and mandibular molars is 4.31 mm (minimum of 3mm and maximum of 8 mm).23 This result helps clinicians to find better decision-making during the management of periodontal disease conditions. Therefore, in some cases where RTL is extremely short (CEJ-furcation=3mm), if there were a CAL of 3mm in the buccal area of a molar (#30 ADA or #46 FDI) with PD of 5mm in this face, for example, it would reach and compromise the furcation area.

Thus, analyzing the case above (CAL of 3mm in the buccal area of a molar with PD of 5mm in the same surface, with Furcation class II involvement, and only two more non-adjacent teeth with the interproximal bone loss [CAL = 1mm and PD = 4mm]): what would be the correct diagnosis of this case ([a] Stage II because of the higher CAL [2mm] with PD=5mm in the buccal area; or [b] Stage III because of the Furcation class II without a 6mm of PD)? This critical review suggests that complexity never should overcome the severity; then, the result for the case above is (a) Stage II (CAL=3mm with PD=5mm, with Furcation class II involvement). Thereby, this article suggests a modification for the Furcation involvement, as follows: Stage I (no Furcation involvement); Stage II (may have Furcation class I or II involvement); and Stages III and IV (may have or not have any Furcation involvement). Previously, the Furcation classes II and III were only considered in Stages III and IV, and Furcation I was not included.

In another similar case, CAL of 4mm in the buccal area of a molar with PD of 6mm in this surface, with Furcation class I involvement, and only two non-adjacent teeth with interproximal bone loss (CAL=1mm and PD=4mm): what would be the correct diagnosis? Again, following the suggestion of this critical review, the complexity factors should never overcome the severity factors; then, the result for this new case is Stage II (CAL=4mm). This review suggests including Furcation class I involvement in Stage II of periodontitis. Even though there was PD=6mm in this case, it should not overcome the severity found.

Probing depth (PD)

Keeping PD as the primary initial clinical criterion is a good clinical option because it can be easily obtained.16 PD can indicate the presence of an active periodontal-diseased pocket,24 and deep pockets have a higher risk of disease progression than shallower pockets.25 Therefore, at the same time or appointment that the clinician is analyzing the PD, it is highly recommended to evaluate gingival margin position (GM) and CAL in order to be less time-consuming, which also depends on the level of experience of the professional and assistant. To correctly work in Periodontics, CAL must be obtained (the most important parameter); PD can be a primary evaluation factor but not to define periodontitis diagnosis.

As a “tip” or suggestion to quickly find CAL (which must be confirmed with the RBL analysis), it is possible to calculate it as demonstrated in Table 3. It is important to understand that it is a formula to quickly calculate the CA level (typically, the “normal” position of the GM is (+)1mm above CEJ; but it is possible to find (+)2mm or sometimes more); in order to have higher accuracy, the position of the GM must be clinically measured detecting the CEJ and real position of GM ([+], above CEJ; [-], below CEJ).

Some scenarios bring much confusion for periodontitis diagnosis (staging) if it follows the initial evaluation using PD. The metric typically accepted as a normal PD is up to 3mm. Therefore, observing the PD considered for the complexity of a case, 4mm is an adequate metric for Stage I, which is well-registered in the new classification. This article suggests that PD=4mm must be without recession involvement or, if the recession is present, to do the simple calculation presented above (PD – GM [the result must be around 1 and 2]). It is necessary to remember that any GM value must be positive if coronal to CEJ, zero “0” if GM=CEJ, and negative if there is any recession.

Similarly, it can be observed that the PD proposed in Stage II was ≤ 5mm; it must be kept. This review suggests only adding without recession involvement or doing the simple calculation PD – GM, which should result between 3 and 4 if the recession is present.

To avoid creating questions for Stages III and IV, which initially considered the necessity of finding PD ≥6mm during the clinical evaluation, this critical review suggested considering the presence of any PD for Stages III and IV. This suggestion is based on the possibility of a case with multiple CAL ≥5mm with generalized recession and PD lower than 6mm for all teeth. Again, it is worth remembering that this review suggests that complexity factors should not overcome the severity factors, except between Stages III and IV.

Mobility

This parameter was not directly considered among the complexity factors, but this critical review suggests including it in Stage II (mobility 1), Stage III (mobility 1 and 2), and IV (any mobility). A tooth with mobility 3 is considered hopeless, and even though it was considered in Stage IV, it is most adequate as a hopeless tooth (TLP).

Bite collapse, drifting and flaring

There is confusion in the literature about using this parameter. The initial idea of the presence of this content (bite collapse, drifting, and flaring) is strictly associated with the absence of teeth (≥5 teeth), which caused a need for complex rehabilitation. Suppose patients have no tooth loss or TLP of ≤4 teeth (without a need for complex rehabilitation) presenting any type of drifting or flaring, with CAL ≥5mm and RBL extending to the middle third of the root and beyond. In that case, it cannot be a justification for changing the diagnosis from Stage III to Stage IV.

Again, this critical review suggests that no one parameter from complexity must overcome severity parameters; an exception must be respected only for complexity factors between Stages III and IV that can change the initial Stage III or IV obtained, only between themselves, according to the complexity found in the case (Figure 2); however, for the case above, there is no justification to consider it.

‘Gray zones’ for staging periodontitis

Ravidà et al.,26 Abrahamian et al.,27 and Gandhi et al.28 agree that more efforts are needed to improve diagnostic agreement among professionals, especially general dentists, for the case definition of periodontitis. Their studies identified “gray zones” using the new classification system, which must be revised and clarified; they can result from the experts’ non-concordant opinions and diagnoses. Typically, most of them involve conflicting severity and complexity factors among Stages III and IV.

One of the gray areas to discuss in this critical review is “tooth loss due to periodontitis” (TLP). The new classification acknowledges TLP as part of the severity of staging periodontitis. Therefore, if the professional has no longitudinal patient data available to support the missing tooth allocation as TLP, the patient will be the source of information. The literature suggests easy ways to obtain it, such as asking about tooth mobility or cavities (correlated symptoms). If history cannot be provided, the tooth loss cannot be considered TLP. However, what is the reliability of this information, if available, to help diagnose the case? As discussed above, this parameter is important, but it is suggested that it cannot be more relevant than CAL and RBL. Thus, this critical review suggests modification that the severity should be obtained following and respecting the cumulative sequence of CAL (1st), RBL (2nd), and TLP (3rd). The TLP may be present or not in Stages I, II, and III; therefore, it can be a factor of differentiation between Stages III and IV.

Another “gray zone” point to discuss is whether complexity factors can shift a patient’s severity level. Before, as clearly reported in the new classification,26 shifting upwards can be performed if a patient has been staged before and had significant disease progression after periodontal therapy, resulting in increased severity and/or more complex treatment needs. Then, the stage must be shifted upwards during the subsequent examination.14 Otherwise, for shifting downwards, even though the severity of CAL and/or RBL can substantially be reduced after periodontal treatment in cases of successful results or regeneration, the patient is advised to retain the Stage initially assigned. The recommendation of this critical review for shifting upwards is keeping the same concept adopted by the new classification; whereas shifting downward is based on the fact that periodontitis is a tooth-dependent disease, and if the patient holds the previous diagnosis for at least 12 months, with all values for CAL, PD, RBL, and GM improved or stable within that period (12 months), a new diagnosis must be performed.

Returning to the question above (complexity factors can shift a patient’s severity level), stage IV periodontitis has many parameters to be evaluated in complexity (masticatory dysfunction, secondary occlusal trauma, bite collapse, drifting, flaring, severe ridge defects, less than 10 opposing pairs), besides CAL, RBL, and TLP (≥5 teeth), which is different from Stage III, needing for multidisciplinary rehabilitation. In contrast with Stage III, which also presents severe periodontal tissue support loss, Stage IV periodontitis involves a larger segment of the dentition. Thus, stage I or II periodontitis cases can never be upshifted to Stage IV directly based on the complexity factors alone because of the number of complexity factors involved (it is necessary to observe the severity factors, too). Some examples that are classified directly as Stage IV by mistake involve (a) partially edentulous cases with <10 opposing pairs, where tooth loss is due to reasons other than periodontitis (primary occlusal trauma, with loss of vertical dimension of occlusion or tooth drifting); (b) patients who present with all posterior teeth lost due to unknown reason, and the clinician infers the justification based on the oral and general health history and assessment of the current periodontal status.26 In order to find a simple solution, this critical review suggests that any complexity factors found should never overcome the severity factors to change the Stage. If this parameter is followed, many mistakes in diagnosis will be avoided. The exception for this parameter suggested must be considered only for complexity factors between Stages III and IV; they can have interchangeability if the initial Stage III or IV was obtained through severity factors.

Reassessing clinical cases with the ‘gray zones’ published in the literature using the new suggestions for staging periodontitis

This part includes three articles that published cases reporting “gray zones” for periodontitis; they must be included and discussed because of their importance in the literature. The cases were presented with the original result found (left) and suggested modification (right).

1. Sirinirund et al.29 reported 2 cases with “gray zones” for periodontitis. Both cases had generalized periodontitis.

(a) Case 1 was a 46-year-old Caucasian female, former smoker (10 cigarettes/day for 5 years and quit for more than 20 years), with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (HbA1c=9.4%) and morbid obesity (body mass index=50.6 kg/m2); patient had deep overbite along with tooth drifting/flaring in the upper anterior of the maxilla, without substantial loss of vertical dimension, mobility, or masticatory dysfunction; the patient had no missing teeth. The greatest CAL and PD found was 11mm (#5 ADA / #14 FDI), with GM=0, RBL to mid-third of root length or beyond, with a history of no tooth loss. The final diagnosis was between Stages III and IV. After deep analysis, considering that the patient did not lose any teeth due to periodontitis and considering the current efficacy of periodontal regeneration for infra-bony defects, the authors diagnosed the patient as Stage III (Figure 3-left). If all the sequences recommended by this review are followed (Figure 3-right) and it does not consider drifting/flaring for this case (not as a result of TLP, as recommended), the direct diagnosis was Stage III, similar to those found in the original article.

(b) The 2nd case was a non-smoker 34-year-old Caucasian female with obesity (BMI: 39.2 kg/m2), taking no medication, and without any significant diseases or conditions. No tooth loss but with considerable recession in the lower anterior teeth, mainly in the left central incisor (#24 ADA / #31 FDI), which had vertical bony defect apically extended (#24 / #31). The highest PD was 7mm, and CAL was 11mm; RBL extending to the mid-third of root and beyond, with generalized mobility with localized secondary occlusal trauma (#24- #25 ADA / #31-#41 FDI). Initially, the case was qualified as Stage III or IV periodontitis; the authors defined the final diagnosis as Stage III. Observing the scenario for the classification (Figure 4-left) and comparing it with the table suggested by this review (with modifications) (Figure 3-right), it is possible to verify that the severity defined the case as Stage III and the complexity factors involved great part of the complexity of Stage III. Even though the complexity factors are shared between stages III and IV, summed of the secondary occlusal trauma found, the severity factor (tooth loss) was decisive in defining and keeping the case as Stage III (which was easily found compared).

2. Siqueira et al.30 published 2 complex cases with “gray zones” for periodontitis, which were challenging to define the diagnosis. The authors provided essential thoughts for interpretation and diagnosis.

(a) The first case was an 83-year-old male with a history of congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, artificial aortic valve replacement, heart attack, controlled hypertension, BOP 87%, overweight (body mass index: 29.1 kg/m2), sleep apnea, allergy to penicillin, past-smoker (quit 50 years ago). The worst CAL observed was 10mm, PD of 7mm, at #14 (ADA) or #26 (FDI). RBL was generalized, with moderate horizontal bone loss; some areas extending to the mid-third of the root; vertical bony defect was noted on #1 (ADA) or #18 (FDI), which had drifting. Four teeth were lost but for unknown reasons. Furcation class 2 (#30 ADA / #46 FDI), moderate ridge defect, >10 opposing pairs were found, with >84% of teeth affected. Mobility degree 1 in more than 5 teeth. Traumatic occlusal forces were found (secondary occlusal trauma). The case was classified with stage III generalized periodontitis (Figure 5-left). Therefore, observing the new table proposed and the case with a higher level of complexity, it should be classified as Stage IV. This fact is supported by the severity factors found and the cumulative complexity factors present simultaneously in stages III and IV; moreover, it is necessary to sum up two other specific complexity factors explicitly found in stage IV. All these facts justify the diagnosis of stage IV periodontitis.

(b) The 2nd case was a 73-year-old male with controlled hypertension, obesity (body mass index: 34 kg/m2), irregular heartbeat, type 2 diabetes (HbA1c: 6.5%), and basal cell carcinoma removed years ago; partial edentulism, hyper-eruption, deep bite, severe wear, and loss of occlusal vertical dimension were found. The worst interdental CAL was 12mm (#14 ADA / #26 FDI; without adjacent tooth – not considered) and 8mm (#8 ADA / #11 FDI), with 7mm PD; RBL was generalized mild horizontal bone loss with localized severe bone loss on #5; vertical bony defects (>3mm) noted; absence of 5 teeth by unknown reason. Furcation class 2 (#15 ADA / #27 FDI), moderate ridge defect, mobility class 2. The periodontal diagnosis was stage IV generalized periodontitis (Figure 6-left). Observing all factors reported, it is possible to easily confirm the diagnosis as Stage IV periodontitis (Figure 6-right).

3. Steigmann et al.31 also published 2 borderline cases in “gray zones” for periodontitis.

(a) The first case was a systemically healthy patient (66-year-old female) with a family history and diagnosis of periodontitis at the age of 14 years. The patient had signs of parafunctional bruxism and clenching, with secondary occlusal trauma, severe ridge defects, and drifting; 8 missing teeth (4 due to periodontitis). The patient had generalized interproximal CAL ≥5 mm (>30% of the teeth) with PD >6 mm; generalized RBL extending to the mid-third of the root, and three localized vertical defects (Figure 7-left). The authors diagnosed it as stage III periodontitis, justifying there was no need for complex rehabilitation given the patient’s current occlusion. Considering the new suggestions from this critical review (the presence of teeth mobilities classes 1 and 2) summed to some not well-documented points observed (description of 4 TLP in the text and it was registered 5 in the figure (Table 7-left); the presence of hyper-eruptions and bilateral altered Spee curvature), all those are factors that bring more complexity to rehabilitating the case. Then, observing the new classification and the suggestions for modification, this case fits much better in stage IV (Equation 7-right).

(b) The 2nd case was a systemically healthy patient, a 64-year-old female with no family history of periodontitis. She had no TLP (8 missing teeth); had signs of parafunctional bruxism with secondary occlusal trauma; several periapical lesions; and one implant with peri-implant disease. The patient has generalized interproximal attachment loss ≥5 mm (>30% of the teeth), mobilities class 1 and 2, generalized horizontal bone loss with areas of vertical bony defects; and generalized horizontal RBL extending to the coronal third of the root; 8 localized vertical defects that extend to the mid-third of the root or beyond; the worst PD was 13mm and CAL of 12mm/13mm. The authors did not count hopeless teeth (6 teeth) in the initial assessment for TLP; therefore, they considered that after extractions, the patient will need complex rehabilitation (resting ten occluding pairs). The patient received the diagnosis of stage IV periodontitis (Figure 8-left).

Observing the scenario and considering the hopeless teeth, mobility, need for complex rehabilitation, and the severity factors (favoring stage IV) and complexity factors (involving most of stage IV [it can have the complexity factors of stage III too]), the results of the new suggested table (modifications) also resulted and confirmed it as stage IV periodontitis.

Final considerations

The implementation of a new classification system typically poses challenges for its clinical application and also in education. Establishing this new classification must be seen as a process, a transitional phase, which may have adjustments for improvement to be made as effective as possible. Several articles already investigated the diagnostic accuracy of this new classification, with the presence of periodontal experts, general dentists, and students. Abrahamian et al.27 concluded that professional clinical experience (postgraduate students, academics, and periodontal experts) is less important when applying the new classification system (no significant differences for inter- and intra-rater reliability). Likewise, Marini et al.32 and Ravidà et al.26 showed moderate consistency and concordance of the differently experienced examiners to the gold standard. Therefore, it is recommended that new investigations apply this new flowchart/suggested modifications in order to validate the decision-making periodontal diagnosis, which intends to facilitate the periodontal clinical assessment, even if it seems complex at the beginning.

Once again, our suggestion in this critical review is to organize the knowledge better and keep the same sequence/assessment parameters for all stages of periodontitis. Then, it is strongly recommended to check and keep the parameters analyzed cumulatively: first severity and after complexity, following the sequence: 1st – CAL (also obtain PD and GM), 2nd – RBL, 3rd – TLP (for decision between Stages III and IV); then, the complexity factors, as demonstrated in Figure 2. It is important to highlight that if the patient has TLP (3 teeth), but the worst site CAL is 4mm, the Stage must be kept on Stage II, respecting the cumulative sequence suggested (CAL is more important for the case scenario than TLP).

It is worth remembering this review suggests that never one complexity parameter can overcome a severity parameter to change the Stage obtained through CAL (1st), RBL (2nd), and TLP (3rd). An exception must be respected only for complexity factors between Stages III and IV that can change the initial Stage III or IV obtained by the severity analysis, but only between themselves, according to the complexity found in the case (Figure 2).

Then, after reading all the articles and observing the flowcharts and sequence proposed, in order to improve the clinician’s decision-making diagnosis, this critical review developed and included within this article a new complete periodontal flowchart (based on the included articles), suggesting a full sequence for periodontal assessment, already including the modifications proposed on Staging (Periodontitis) (Figure 9).

Unquestionably, the new Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions (2018) is one of the most interesting evolutions of classification systems that permit the diagnosis of periodontal/peri-implant diseases. Therefore, observing the difficulty around the world in staging periodontitis, this critical review deeply analyzed this question.

This critical review suggests, specifically, that complexity parameters cannot overcome the severity parameters and to strictly follow the sequence for diagnosing: CAL (1st), RBL (2nd), and TLP (3rd), where the 1st cannot be surpassed by the 2nd or 3rd, and similarly, the 2nd cannot be surpassed by the 3rd parameter. An exception is permitted only for complexity factors between Stages III and IV that can change the initial Stage (III or IV) obtained through the severity analysis, but only between themselves (Stages III and IV), according to the complexity found. Moreover, for patients without tooth loss or with TLP of ≤4 teeth (without need for complex rehabilitation) and presenting any drifting or flaring or a secondary traumatic occlusion, it cannot be a justification for moving the diagnosis from Stage III to Stage IV.

Furthermore, some modifications for staging periodontitis are also suggested:

– for severity:

(1) TLP summed up a hopeless tooth to be extracted (bone present only in the apical third of the root and mobility class 3): Stages I and II may have tooth loss;

– for complexity:

(1) Stage I: should be considered PD ≤4 mm without recession or the calculation PD minus GM resulting in 1 or 2mm; and this stage cannot have furcation involvement;

(2) Stage II: should be considered PD ≤5 mm without recession or the calculation PD minus GM resulting in 3 or 4mm; and may have furcation I or II involvement and mobility class 1;

(3) Stage III: this stage can have any PD; may have any class of furcation involvement; may have vertical bone loss; and may have tooth mobility 1 or 2;

(4) Stage IV: this stage can have any PD; may have any class of tooth mobility; and may have < 20 remaining teeth.

Conclusions

It was possible to conclude that there is instability and “gray zones” in the staging step of Periodontitis. This is due to a lack of priority and an organized order sequence, where the most important parameters were overcome by others. Thus, this critical review intends to create and stimulate a debate for improving specific points of the new classification, specifically in staging periodontitis. Then, we introduced a new table with the modifications suggested and a new full flowchart for the sequence of the periodontal diagnosis. However, it is required that experts in periodontics critically assess and validate the modifications proposed to verify how they clinically facilitate finding the periodontal diagnosis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.