Abstract

Background. Oral health behaviors are the primary determinants of dental health. They undergo modification and stabilization during adolescence, and can persist into adulthood.

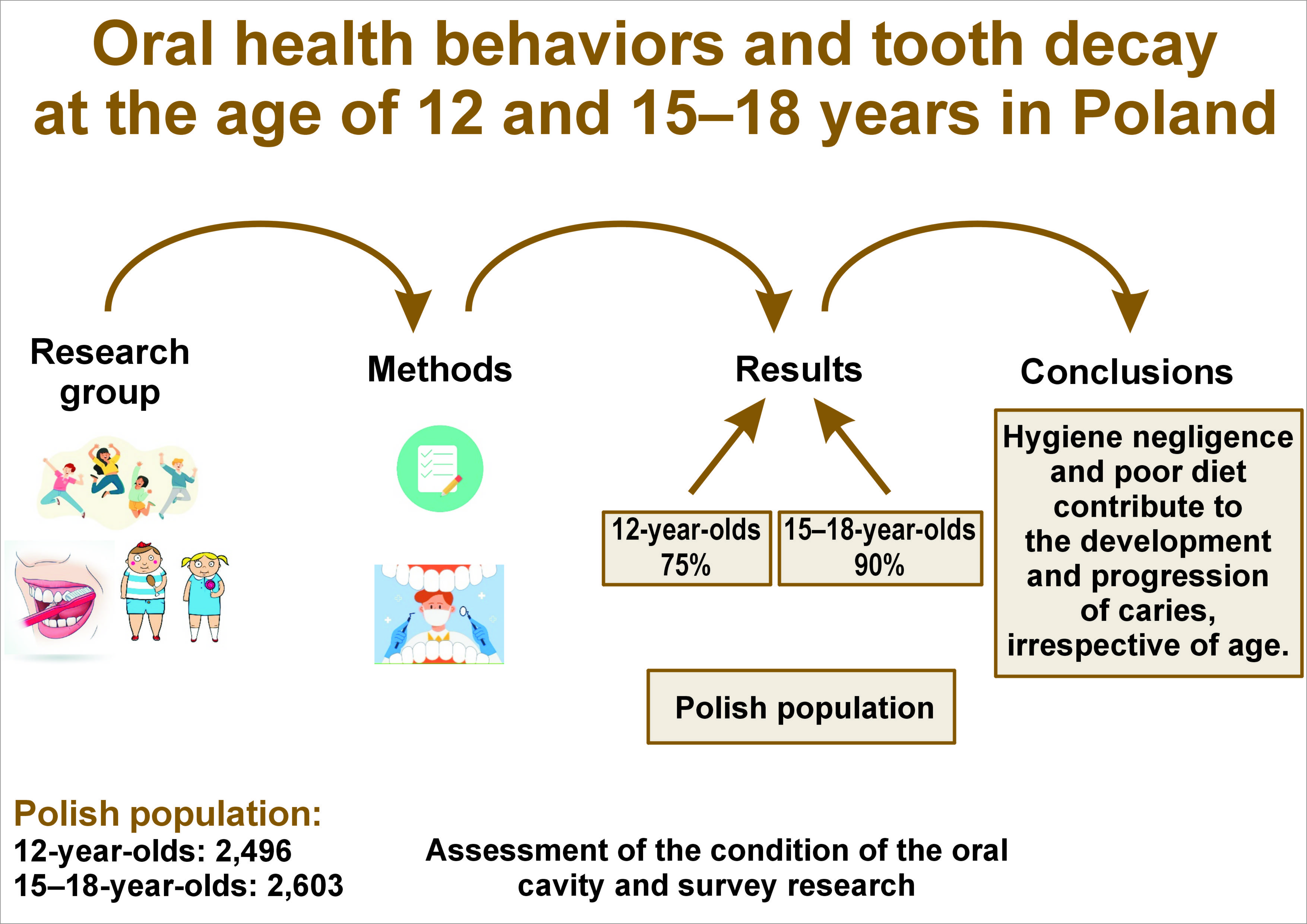

Objectives. The aim of the study was to assess the oral health behaviors of individuals aged 12 and 15–18 years, and to examine the impact of these behaviors on the occurrence and severity of dental caries in different age groups.

Material and methods. A cross-sectional oral health national survey was conducted between 2016 and 2020, encompassing a total of 5,099 participants, including 2,496 individuals aged 12 and 2,603 participants aged 15–18 years. The presence of non-cavitated decay (D1–2), cavitation (D≥3), and missing (M) or filled (F) status at the tooth (T) or surface (S) levels was evaluated. The prevalence of caries (D≥3MFT > 0), as well as the mean values of the D1–2, D≥3MFT and D≥3MFS indexes were assessed. The questionnaire contained information on sociodemographic factors, oral health behaviors and the participants’ diet.

Results. The prevalence of dental caries was 75% among 12-year-old and 90% among 15–18-year-old individuals. Indicators associated with a reduced likelihood and lower severity of dental caries in both groups included prophylactic dental visits (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) (12-year-olds): 0.83; AOR (15–18-year-olds): 0.64) and brushing teeth at least twice a day (AOR (12-year-olds): 0.72; AOR (15–18-year-olds): 0.59). Frequent consumption of sweet products and chips by 12-year-olds increased the likelihood of developing and exacerbating tooth decay. In the older group, the risk of developing caries was associated with the consumption of sweets and sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages.

Conclusions. Poor oral hygiene and inadequate diet are conducive to the development of caries, with the condition being exacerbated by these factors regardless of age. However, the influence of diet appears to be more pronounced in less mature dentition. The benefits of dental visits, oral hygiene practices and a preference for mineral water in quenching thirst have also been demonstrated. The health behaviors exhibited by older and younger adolescents are comparable, suggesting that these habits may persist into adulthood.

Keywords: diet, adolescence, dental caries, hygienic behavior

Introduction

Dental caries is a prevalent health problem that persists throughout an individual’s life. The disease impairs a person’s quality of life by causing pain, difficulty eating and speaking. The etiology of tooth decay is multifactorial, involving inadequate plaque control, dental defects, frequent consumption of dietary carbohydrates, characteristics of saliva, and/or hereditary genetic factors.1, 2, 3, 4 Tooth decay can also lead to pulpopathy, periodontal infections, tooth loss, and the need for endodontic treatment. The consequences of tooth decay include absenteeism from school or work, and high costs incurred for treatment.5, 6, 7, 8 In recent years, the incidence of tooth decay in Western countries has clearly decreased, although the condition still remains a significant health problem.9, 10 According to the World Health Organization (WHO),11 the prevalence of dental caries among school-aged children is estimated to be as high as 60–90% in some countries (e.g., Lithuania, Portugal, Hongkong). A study of 9 European countries (e.g., the Czech Republic, France, the UK) revealed that caries affects approx. 52% of individuals between the ages of 11 and 13.12

The prevention of tooth decay can be achieved through the implementation of proper health behaviors. In childhood, the primary responsibility for the oral health of children lies with their parents, who must ensure their children receive the necessary care and instill the appropriate health behaviors. However, as an individual matures and becomes more independent, the responsibility for maintaining optimal health habits shifts increasingly to the child. At the same time, during adolescence, health behaviors undergo modification under the influence of various social and cultural factors. Adolescents frequently engage in behaviors that are detrimental to their health (e.g., consumption of alcohol and other stimulants, smoking). These behaviors not only contribute to the development of tooth decay, but also become permanent and persist into adulthood, exacerbating the health problem.13, 14, 15, 16

Adolescence is defined as the developmental stage between childhood and adulthood. According to the WHO, an adolescent is an individual between the ages of 10 and 19.17 This developmental stage is subdivided into 3 phases, namely early, middle and late adolescence. However, the authors point to shifts in individual age categories.17 There is a discrepancy between the studies as to the exact time division of the mentioned periods of adolescence.18 In our work, we distinguished between the early adolescence (11–14 years) and middle adolescence (15–18 years). The susceptibility of adolescents to factors modifying their health behaviors, their ability to accept standards, and short- and long-term health risk assessments vary during early and middle adolescence.19 There are also differences in the susceptibility to caries in these phases, resulting from different degrees of maturity of tooth tissues. Typically, individuals aged 12–13 years possess full permanent dentition, with the exception of third molars. However, premolars and second molars are often characterized by immaturity, which can facilitate the onset of caries and the rapid spread of the disease process within tooth tissues. The risk of developing tooth decay is highest within the first 2–4 years following tooth eruption. This period is characterized by the exposure of the enamel to the oral cavity environment, which initiates changes known as post-eruptive maturation. Consequently, the susceptibility to cariogenic factors in tooth enamel is lower at the age of 15–18 compared to the enamel of an individual at the age of 12; however, this susceptibility remains higher than that observed in adults. Therefore, the age of patients is a particularly important factor when examining the incidence of caries.20, 21

The high susceptibility of immature permanent teeth to caries and the rapid spread of the disease underscore the significant role of adolescent health behaviors. Therefore, the aim of the study was to assess the oral health behaviors of individuals aged 12 and 15–18 years, and to ascertain how these behaviors influence the prevalence and severity of tooth decay.

Material and methods

The cross-sectional studies included adolescents aged 12 and 15–18 years from all Polish voivodships. The study groups were selected in a three-tier draw (district/community, city/village, and school levels). The inclusion of the educational institutions in the research was contingent upon their directors’ consent. The inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: patients aged 12 or 15–18 years; and the provision of signed informed consent to participate in the study. The signed consent forms for the sampled adolescents, along with informational letters detailing the study’s scope, were distributed to the parents by the teachers. To maintain anonymity, each participant was assigned a unique code number, which was included on the questionnaire and clinical trial card. The participants were not offered any additional incentives to participate in the study, apart from feedback on the health status of their dentition.

The data regarding the total number of adolescents was retrieved from the Central Statistical Office.22, 23 The size of the sample under study was calculated based on literature data concerning caries prevalence in this age group in Poland, i.e., about 85.4% were caries-affected. Assuming a 95% confidence interval (CI) and ±4% error tolerance, it was determined that approx. 600 subjects in each group represented a minimum sample size. The study sample was determined by selecting 3,000 12-year-olds and 3,000 adolescents aged 15–18 years. The total number of individuals enrolled in the study was 5,099, including 2,496 12-year-olds (50.4% from rural regions and 50.9% females) and 2,603 individuals aged 15–18 years (49.6% and 52.6%, respectively). The reasons for the exclusion of 901 subjects from the study were as follows: lack of signed informed consent (33.0%); absence from school on the day of the study (22.8%); or an incorrectly completed survey questionnaire (43.7%).

The study incorporated a questionnaire examination and a clinical assessment of the dentition. The survey contained closed-ended questions, with only 1 possible answer. The questionnaire inquired about various socioeconomic factors (place of residence, self-assessed financial situation and mother’s education level), hygienic behavior (frequency of toothbrushing, conscious use of fluoride toothpaste, and the type and frequency of hygiene tools usage), diet (frequency of consumption of certain foods), and the use of dental care. The questionnaires were completed by students at school during classes. The questionnaire was developed in accordance with the WHO guidelines.24 It has been used in numerous studies that have been conducted as part of the monitoring of the health of the Polish population.

When presenting research on the frequency of dental caries, it is worth mentioning the relationship between the incidence of dental caries and certain congenital defects, e.g., those related to the developmental defects in enamel4 or malocclusion.5 Malocclusion can impede patients’ ability to maintain proper oral hygiene, which can lead to the development of dental caries. However, it should be acknowledged that the fundamental principle of epidemiological research is the randomness of the studied population. Accordingly, the study sample is presumed to be a representative of the general population, which necessitates the consideration of the possible occurrence of general health problems. The epidemiological studies presented have considered the factors recommended by the WHO.24

Clinical trials were conducted by dentists following training and calibration with a reference investigator (24 dentists participated in the research). The studies were conducted under artificial lighting, using a mirror and a WHO 621 probe, in accordance with the study rules and criteria for the classification of the WHO clinical conditions.24 As part of the study, the condition of the dentition was assessed by examining each tooth surface in successive quadrants. Caries was evaluated using the ICDAS-II (International Caries Detection and Assessment System), where codes 1 and 2 were treated as non-cavitated decay (D1–2) and code 3 was classified as a carious cavity (D≥3).25 The number of permanent teeth present in the oral cavity, the total number of teeth, and the surface of permanent teeth with D1–2 and D≥3, lost due to caries (M) or with fillings (F) at the tooth (T) or surface (S) levels, were determined. The mean values of the D1–2, D≥3MFT and D≥3MFS indices were calculated. The number and percentage of patients with caries (D≥3MFT > 0) were determined.

The level of fluoride in drinking water in Poland does not exceed 0.5 mg/L. In Poland, children and adolescents have access to free dental care, which encompasses treatment and prevention. The present survey was conducted as part of the project entitled “Monitoring of oral health condition in Polish population in 2016–2020”, supported by the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Poland. The Bioethics Committee of the Warsaw Medical University provided its consent for the study (KB/190/2016 and KB135/2019).

Statistical analysis

A comparison of the test results between the observation physicians and the reference physician was made using the Cohen’s kappa coefficient. The studied variables were presented as percentage or mean and standard deviation (M ±SD). Comparisons of the means between the 2 groups were made using the t-test, while comparisons of percentages were conducted using the χ2 test. In order to determine the relationships between pairs of variables, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was performed. To assess the impact of different factors on the prevalence of caries in children, a bivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted, in which the impact of each individual factor was considered, as well as a multivariate logistic regression analysis, in which simultaneous impact of several factors was assessed.

The logistic regression analysis yielded odds ratios (ORs) for the relative risk of caries development, with CIs at the 95% level. An AOR was calculated, where socioeconomic factors were the constant confounding factors, and hygienic and/or dietary behaviors were the variables. The analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA), Statistica 10 software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, USA), and the R 3.2.0 software package (https://cran-archive.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.2.0).

Results

The Cohen’s kappa coefficients between the reference investigator and the other researchers (dentists) ranged from 0.963 to 1.000. The prevalence of dental caries in the entire sample was 83% (4,215 participants). Within the 12-year-old group, 1,869 participants (75%) were diagnosed with caries, while in the 15–18-year-old group, caries was diagnosed in 2,346 participants (90%). The intensity of caries was more than 2 times lower in the younger age group than in the older age group (Table 1).

The socioeconomic characteristics and oral health behaviors of the subjects are presented in Table 2. Seven hundred sixty-four (30.6%) of the surveyed 12-year-olds were not aware of their mother’s level of education, and 630 (25.2%) did not specify their family’s financial situation. In the older group, this situation occurred in 337 (13.0%) and 485 (18.6%) respondents, respectively. As many as 858 (34.4%) respondents aged 12, and 1,283 (49.3%) respondents aged 15–18 were unaware whether the toothpaste they used contained fluoride. Among the 12-year-olds, 437 (17.5%) consciously used fluoride-free toothpaste, while this practice was adopted by 194 (7.4%) of the older adolescents. In the older group and among 1,610 participants aged 12 years, additional questions were posed regarding the frequency of still mineral water consumption.

Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed a relationship between the occurrence and severity of caries, as well as socioeconomic factors and oral health behaviors (Table 3). However, there was no statistically significant relationship regarding the use of liquid mouthwash and the consumption of vegetables and fruits. The logistic regression analysis revealed that, irrespective of subjects’ age and their hygienic and dietary behaviors, attendance at check-up visits was associated with a reduced likelihood of caries occurrence and severity (AOR for 12-year-olds: 0.83 (0.69–1.00), p = 0.045; AOR for 15–18-year-olds: 0.64 (0.49–0.83), p < 0.001) (Table 4,Table 5).

In relation to oral hygiene practices, the occurrence of caries was found to be less probable and less severe among individuals who brushed their teeth twice daily. This effect was slightly attenuated by dietary habits (AOR for 12-year-olds: 0.72 (0.59–0.87), p < 0.001; AOR for 15–18-year-olds: 0.59 (0.43–0.80), p < 0.001). In none of the groups did the use of floss affect the likelihood of caries occurence. However, in both the younger and older groups, the D≥3MFS values were statistically significantly lower. Considering the dietary behavior, the results indicated that caries was more likely to occur among children aged 12 years who consumed sugar-sweetened beverages, tea with sugar, chips, sweetened juices, chewing gum with sugar, and biscuits at least once a day (Table 4). The younger group also showed a tendency toward higher D≥3MFT and D≥3MFS values. The introduction of hygienic behavior as a confounding factor into the statistical model did not alter, nor did it slightly reduce, the negative impact of erroneous dietary habits. In the group of 12-year-olds, there was no significant effect of mineral water consumption on the prevalence of caries.

The impact of dietary habits on the occurrence of dental caries in the older group was less pronounced (Table 5). The likelihood of tooth decay was increased only by the consumption of sweets (candies and carbonated drinks, such as cola or lemonade, and chewing gum with sugar). The importance of these factors remained unaltered by hygienic behavior; however, frequent consumption of cariogenic products did affect the severity of tooth decay. Furthermore, while the consumption of still mineral water did not influence the likelihood of developing dental caries, it was observed that individuals who preferred it to quench their thirst exhibited lower D≥3MFT and D1–2 values compared to those who consumed water less than once a day.

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrated the prevalence of inappropriate oral health behaviors among adolescents, a finding that aligns with the reports from the literature.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 These behaviors were accompanied by an increase in the incidence of caries and the values of D≥3MFT, D1–2 and D≥3MFS with age. This finding is consistent with the notion that tooth decay is cumulative and chronic.31, 34 The incidence of caries in the older group was 15% higher, while the mean D≥3MFT value doubled. This suggests that caries occurs at a younger age, and persistent causal factors contribute to the continuous progression of the disease process. At the same time, the average extent of cavities in both groups was comparable. In the older group, the carious cavity covered an average of 1.4 tooth surfaces, while in the younger group, it was 1.3. The lower prevalence of teeth with caries and the similar average number of tooth surfaces with carious cavities, as well as the higher number of teeth without cavities in younger adolescents compared to the average, may be the result of greater susceptibility of tooth tissues.

The statistical analysis confirmed that socioeconomic factors and oral health behaviors are statistically significantly correlated with caries parameters. It is worth emphasizing the relationship between the occurrence of tooth decay and rural residence in the younger group, and with the female sex among older adolescents. This finding is in contrast to the results of a study conducted on adolescents in Portugal, Romania and Sweden, where the severity of caries was found to be lower in girls and similar in urban and rural regions.29 The differences between rural and urban regions are becoming indistinct in many countries, yet the correlation with sex is emphasized. Women are generally more prone to tooth decay.35 The lower pH of saliva in women is attributed to physiological factors, such as the effect of sex hormones on the expression of salivary gland genes, and the smaller size of the salivary glands.1, 2, 36 Despite the slightly superior oral health behaviors exhibited by girls, such as reduced consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and more frequent toothbrushing, a predisposition to caries remains.37 The correlation between caries and economic status is less pronounced, but this result is less reliable due to incomplete data on the income of the surveyed adolescents’ families. Similarly, the lack of knowledge among adolescents regarding the fluoride content of their toothpaste hindered the acquisition of a fully reliable result regarding the health benefits associated with its use. More than 30% of the respondents lacked awareness about the fluoride content in their toothpaste. However, it has been shown that the conscious use of fluoride-free toothpaste is associated with an increased prevalence of tooth decay.

Hygiene behaviors and diet are the main modifiable risk factors for oral disease, a notion that has been confirmed by numerous studies.38, 39 The frequency of toothbrushing reported by adolescents has been identified as a reliable predictor of tooth decay, with a predictive capability that surpasses that of clinical oral hygiene assessments.40 The percentage of adolescents who brush their teeth at least twice a day is estimated to be between 53.4% and 90.6%,27, 32 which is in line with the results obtained in this study. The study reaffirmed the importance of brushing teeth at least twice a day, as it has been shown to reduce the likelihood of tooth decay by nearly twofold and, to a slightly lesser extent, its severity. This association remained statistically significant even when controlling for potential confounding factors, such as a static diet, in the model. A study of Finnish adolescents revealed a two-fold increase in decayed teeth (DT) values; however, this increase did not affect the occurrence of caries.32 A limitation of our study was the lack of a question about the frequency of flossing, although even the confirmation of its use had a statistically significant impact on the condition of the teeth. In both groups, the D1–2 and D≥3MFT values were found to be statistically significant in individuals who reported flossing their teeth. Hygiene factors also include the practice of rinsing one’s mouth with liquids. Studies have demonstrated that older age groups tend to rinse their mouths more frequently.30

The second causative factor of tooth decay is excessive sugar consumption. Alarmingly, a significant proportion of Polish adolescents consume foods and beverages with sugar at least once a day. Many authors have documented the high prevalence of processed food consumption, especially sweetened beverages.28, 29, 31 In both age groups examined, frequent consumption of sweets and sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages emerged as a dietary factor increasing the risk and severity of caries. Studies of Romanian adolescents also confirmed the direct impact of excessive consumption of carbonated beverages on the DMFT (decayed, missing, and filled teeth) index.31 Similarly, Methuen et al. established that frequent consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and elevated carbohydrate intake increased the likelihood of DT > 0, and that heightened carbohydrate intake (E%) was associated with more DT in 15–17-year-old adolescents in Finland.39 These results are consistent with our observations, as the average DT values in individuals who frequently consume starchy foods with sugar are higher relative to others.

Excessive sugar consumption, inconsistent dental care and postponing dental visits represent further issues. In Brazil and Portugal, 90.9% and 95.1% of adolescents, respectively, report having visited a dentist at least once.41 As many as 7.5% of Brazilians aged 17–21 have never been to a dentist.42 In our study group, more than 10% of the respondents had not been to the dentist so far, or had not visited the dentist for a significant amount of time and were unable to recall the last visit. Pain was reported as the cause of the last visit by 9.7% of 12-year-olds and 15.9% of 15–18-year-olds. In Romania, 40.6% of adolescents have missed regular annual dental check-ups and only sought treatment when they were in pain.31

The oral health behaviors of individuals in early and middle adolescence groups differ. Although older adolescents were less likely to consume sweetened starchy foods, they demonstrated a marked increase in the daily consumption of sugary gum. A significantly smaller percentage of people in this group consumed fruits and vegetables at least once a day. A favorable difference was an increase in the frequency of mouthwash use. Other hygiene behaviors remained comparable between the both groups. In a study by Jurišić et al., poorer oral hygiene attitudes were observed in the middle period of adolescence compared to the early adolescence.43 The authors associated this with the lower influence of parents on the independence of young people. In our study, individuals aged 15–18 years were significantly more likely to cite toothache as the reason for visiting the dentist. Changes in dietary behavior, such as reduced consumption of sweetened starchy products and replacing them with chewing gum, as well as an increased consumption of mineral water, may be attributable to adolescents’ incorrect perception regarding weight management. At the same time, the less frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables, and the less frequent use of dental services, may be related to a diminished parental influence on their offspring’s behavior.

Limitations

The present study was subject to certain limitations. Behavioral measures were analyzed based on survey responses, which are known to be subject to error resulting from repondents’ desire to present themselves in a favorable light. Additionally, the survey question concerned the use of hygiene tools (dental floss, liquid mouthwash), but did not address the frequency of their use.

Conclusions

The results of the present study confirmed the negative impact of hygiene negligence and poor diet on young permanent dentition, irrespective of age. However, the influence of diet appeared to be more pronounced in less mature dentition. The findings underscore the significance of dental visits, oral hygiene practices, and a preference for mineral water in quenching thirst. The prevalence of inappropriate health behaviors among adolescents is comparable across age groups, indicating a potential for these behaviors to persist into adulthood. Therefore, it is essential to control these factors and implement educational programs that promote healthy lifestyles.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Warsaw Medical University (KB/190/2016 and KB135/2019). All participants provided written informed consent.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.