Abstract

The occurrence of desquamation, shedding and erythema on marginal and attached gingiva is described as desquamative gingivitis (DG). Various autoimmune/dermatological disorders cause DG.

The aim of the present systematic review was to gather information on all possible kinds of treatment for DG, based on specific DG diagnoses.

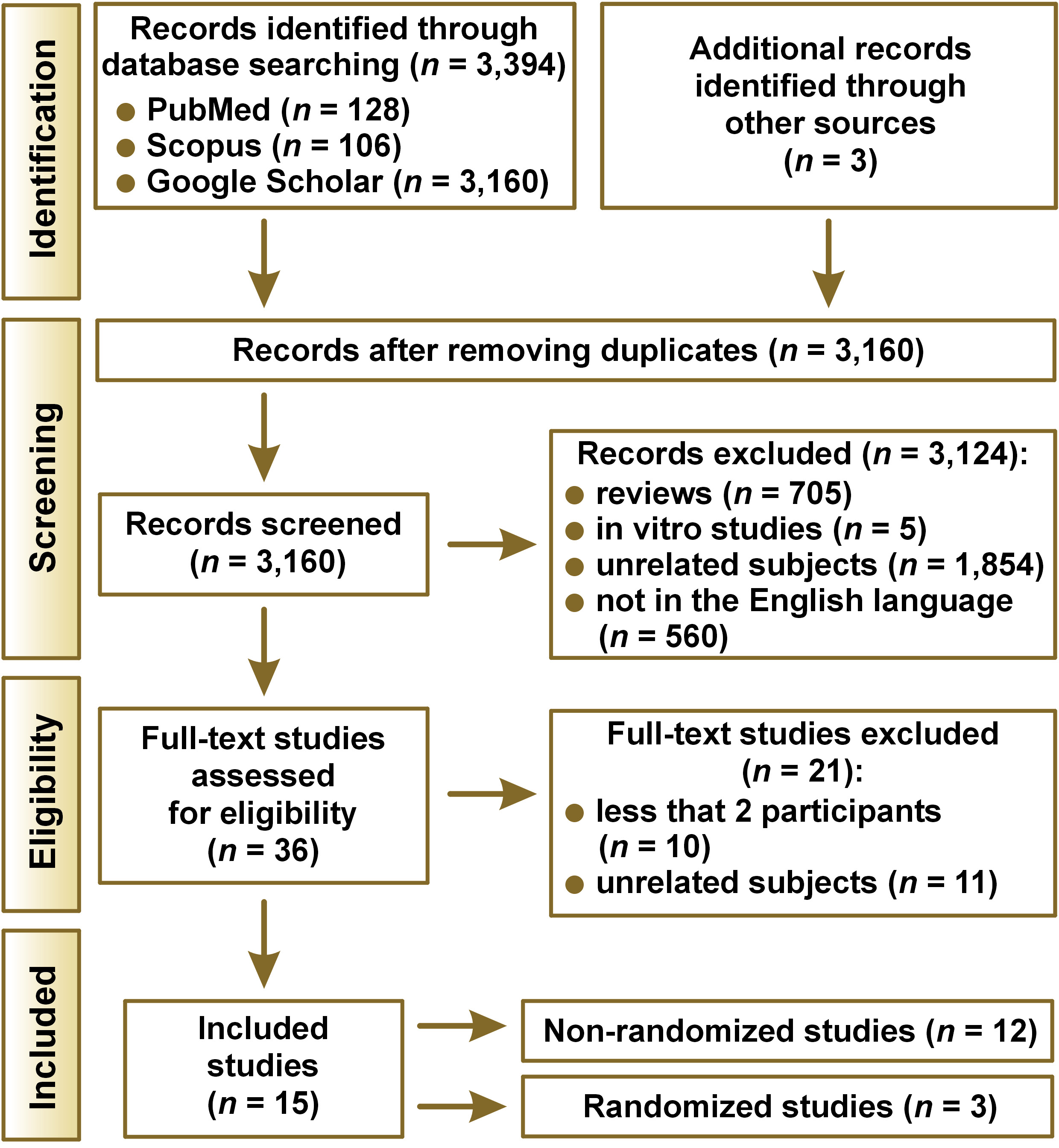

The review was organized following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol. An electronic search was conducted in the PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases, up to April 2022. Reviews, letters and studies with less than 2 participants were excluded.

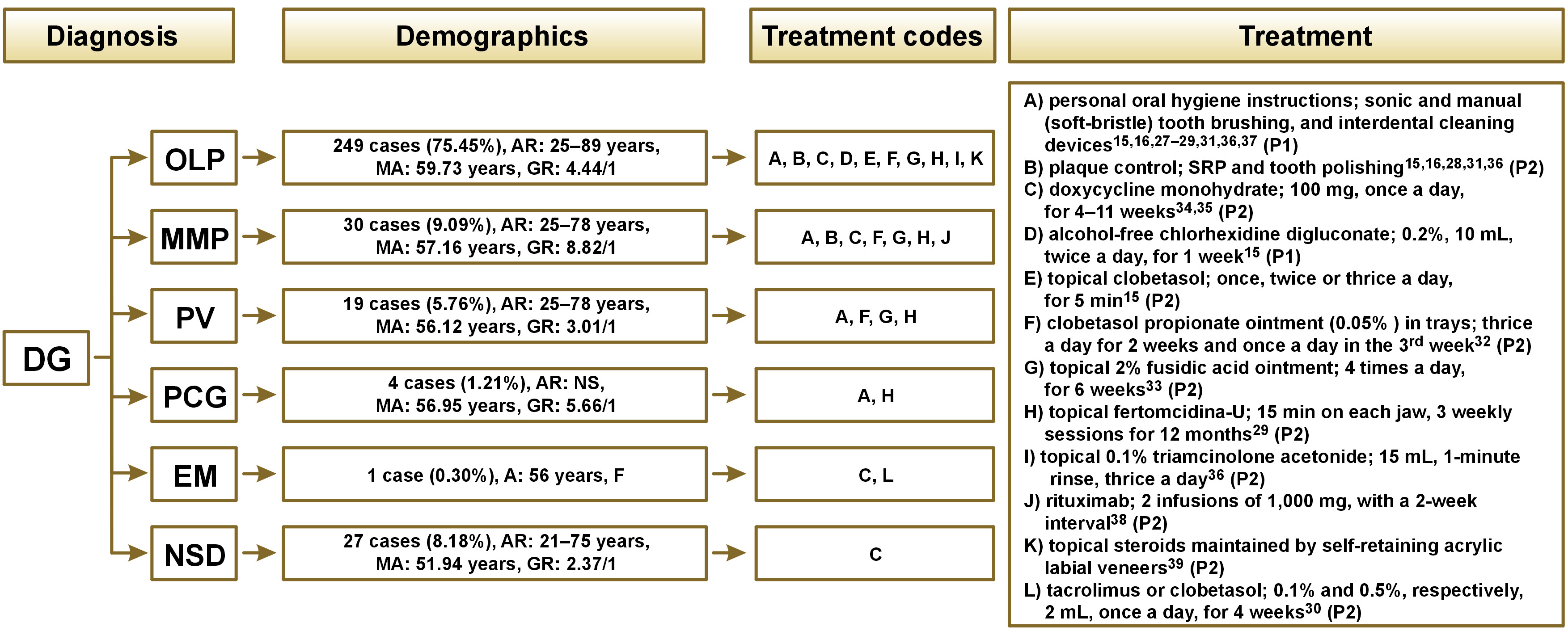

Fifteen publications matched the eligibility criteria: 6 case series; 5 clinical trials; 3 randomized clinical trials (RCTs), and 1 cohort study. A total of 330 patients were enrolled, mostly women (81.52%), with an average age of 57.6 years. Diagnostic characteristics corresponded to oral lichen planus (OLP) (n = 249), mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) (n = 30), pemphigus vulgaris (PV) (n = 19), plasma cell gingivitis (PCG) (n = 4), erythema multiforme (EM) (n = 1), and non-specified diseases (NSD) (n = 27). Oral lichen planus and MMP were eliminated using oral hygiene instructions with topical clobetasol and/or doxycycline monohydrate. Pemphigus vulgaris, PCG and EM were treated with topical clobetasol.

To conclude, each DG case requires personalized treatment, depending on the diagnosis.

Keywords: treatment, oral lichen planus, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, desquamative gingivitis

Introduction

Desquamative gingivitis (DG) is a painful condition with the erythema, bleeding, shedding, and desquamation of gingiva. However, there is no consensus regarding its treatment protocol.

The term “desquamative gingivitis” was initially proposed by Prinz back in 1932 to designate the presence of desquamation, erythema, erosion, and blisters in both marginal and attached gingiva, and even in oral mucosa.1 Erosion and shedding in DG are completely different than plaque-induced inflammation.2, 3

Desquamative gingivitis is a distinctive clinical representation of either hypersensitivity reactions to some allergens or a variety of autoimmune diseases. Some antigens incorporated in mouth rinses, toothpastes, chewing gums, and foods can cause hypersensitivity reactions in patients, showcased in the form of DG.4 In addition, oral lichen planus (OLP), mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), pemphigus vulgaris (PV), plasma cell gingivitis (PCG), erythema multiforme (EM), bullous pemphigoid (BP), systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), linear IgA diseases, dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), and epidermolysis bullosa (EB) are some of autoimmune diseases that stimulate DG signs and symptoms.5, 6 Based on the current evidence, OLP is the most common cause of DG of an autoimmune origin. Desquamative gingivitis emerges more frequently in older women, especially during menopause. However, it can also appear in men and children.7

Desquamative gingivitis presents moderate pain, mainly due to the exposure of the gingival connective tissue. Additionally, plaque-induced marginal inflammation may intensify the pain.7 In some cases, pain is the first manifestation of DG.8 Periodontal studies show that the gingivo-periodontal status is much worse in patients with DG associated with MMP than in the control group.9, 10, 11 Patients with DG related to OLP and PV exhibit deeper pockets and higher levels of clinical attachment loss (CAL).12, 13

Some evidence suggests that DG plays a potentially significant role in increasing the long-term risk of periodontal tissue breakdown.11 As DG is a clinical term representing an oral expression of several different mucocutaneous diseases, its treatment is widely diversified.2, 3, 4 Any treatment protocol must be attempted with the purpose of reducing and controlling the signs and symptoms of DG with minimum side effects.5 Inappropriate home oral hygiene worsens the gingival status of DG patients.14 Therefore, some authors suggest non-surgical periodontal procedures as possible treatment for DG.15 Moreover, specific therapies have been introduced, focusing on the general manifestations of the diseases related to the pathogenesis of DG. Topical treatment, mainly with corticosteroids, has also been prescribed in different forms and dosages. Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants, along with broad-spectrum antibiotics, are among the various drugs administered systematically for DG.16, 17 In addition to corticosteroids, a variety of pharmacotherapies, low-level laser therapies, chlorhexidine, hyaluronic acid, propolis extract, benzydamine hydrochloride mouthwash, and different supplements (e.g., melatonin, vitamin C and vitamin D) have also been assessed for the treatment of DG.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are no comprehensive guidelines or instructions for treating DG. Two systematic reviews have been conducted, focusing on the management of DG.24, 25 However, many more studies, procedures and protocols could be included. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to gather all clinical studies that used any kind of treatment for DG in order to precisely conclude which therapeutic procedures for DG are the safest and most efficient, with the fewest side effects.

Methods

This study has been prepared and organized according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.26

Information sources, the search strategy and study selection

In this review, an electronic search was conducted employing the PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases. Our search was limited to English-language studies published between January 1965 and April 2022. The electronic search was complemented with a manual search of the reference lists of all relevant articles and previous systematic reviews. The following search method was used to find relevant studies in the abovementioned databases: (desquamative gingivitis) AND (treatment OR therapeutics). Eligibility checking, followed by data extraction, was performed independently by 2 reviewers. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of the review were initially applied through the screening of titles and abstracts. Any type of human clinical studies focusing on the treatment of DG (e.g., case series, case reports, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and cohort studies) were included. Systematic and narrative reviews, letters, comments, studies with fewer than 2 participants, in vitro studies, and animal in vivo/ex vivo studies were all excluded from this review. Duplicated studies were recognized and removed. Later, the full texts of the related studies were reviewed for eligibility. In any case of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted.

Data collection

Several data items were used for clinical studies: (1) demographics (gender and age) of the included participants; (2) type of study; (3) number of cases; (4) diagnosis of DG – the relation or association of DG with autoimmune mucocutaneous diseases (OLP, MMP, PV, PCG, and EM) in each case; (5) duration of DG in patients; (6) distribution of DG lesions; (7) previous treatment; (8) treatment protocols, procedures, approaches, and plans; (9) study variables; (10) evaluation period; and (11) outcomes.

Quality assessment

A Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (RoB 2) was applied for both randomized and non-randomized studies to assess the risk of bias. Each study was analyzed with the prefabricated questions created by RoB 2.

Synthesis methods

Taking into account the data extracted from the included studies, it appeared that the methods and protocols used for the treatment of DG were widely diversified. Hence, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis. The descriptive analysis of the data extracted from clinical studies, along with a narrative and graphical synthesis, were performed.

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 displays the diagram of study selection. The initial search yielded 3,397 publications, from which 3,124 irrelevant articles were excluded based on their titles and abstracts. The remaining 36 studies were assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria and the full text of each article was retrieved for further evaluation. After a detailed review, 12 records were retained for data extraction. Three additional records were identified by reading the reference lists in each included study. The selected studies were published between 1987 and 2019. The studies came from Italy (n = 5),15, 27, 28, 29, 30 Brazil (n = 3),31, 32, 33 Norway (n = 2),34, 35 Spain (n = 1),36 Denmark (n = 1),37 Switzerland (n = 1),38 Scotland (n = 1),39 and the United Kingdom (n = 1).16

Results of individual studies

Demographics for all the patients included in the studies are displayed in Table 1. The study type, the distribution of DG lesions, the duration of DG in patients, the previous treatment of DG in patients prior to the study, the treatment procedures and approaches used in the studies, the study variables, the evaluation period, and outcomes for all of the 15 included studies are detailed in Table 2.

Study characteristics

Study design

As specified by the methodological design, different types of studies were as follows: case series (prospective) (n = 6)28, 29, 35, 37, 38, 39; clinical trials (n = 5)15, 31, 33, 34, 36; RCTs (n = 3)16, 27, 30; and a cohort study (n = 1).32

Demographics

The final sample, demographic characteristics and diagnostic characteristics of the enrolled patients (after the elimination of patients who did not complete the treatment and/or follow-ups) are displayed in Table 1. The total number of analyzed subjects was 330 (81.52% women). The age of participants ranged from 21 to 89 years, while the average age was 57.6 years.

Diagnosis

Out of the 15 included studies, in only one RCT, the authors did not declare the diagnosis of DG in their participants (n = 24).30 Rønbeck et al. also had 3 cases with non-specified diseases (NSD).34 However, in the remaining 13 studies, the diagnoses of diseases in participants corresponded to 249 OLP cases, 30 MMP cases, 19 PV cases, 4 PCG cases, and 1 EM case.

Distribution

Some studies reported the exact sites affected by DG,15, 27, 28, 30, 33, 37, 38, 39, while others did not declare the exact gingival sites affected by DG in their participants.16, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36

Duration

The duration of DG was declared in 5 studies, ranging from 1 to 40 years.32, 34, 35, 37, 38

Previous treatment

Previous treatment was not mentioned in 4 studies.27, 28, 29, 30 Some participants were not prescribed any systemic and/or topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids or antibiotics for 6 weeks,35 2 months31, 34 to 3 months15, 31, 36, 37 prior to the study. Other patients16, 32, 33, 34, 38, 39 received treatment prior to the study, detailed in Table 2.

Treatment procedures/approaches

There was a variety of different methods, therapeutics and protocols used for the treatment of DG, such as: oral hygiene protocols28, 29, 31, 36, 37; sonic and manual (soft-bristle) tooth brushing and interdental cleaning devices15, 16, 27, 36; plaque control16, 31; scaling and root planing (SRP)15, 28, 36; alcohol-free chlorhexidine digluconate15; topical fertomcidina-U29; topical corticosteroids (clobetasol)15, 30, 32, 36; immunosuppressive agents (topical tacrolimus)30; topical fusidic acid33; doxycycline monohydrate34, 35; topical steroids maintained by self-retaining acrylic labial veneers39; and rituximab.38 Evaluation periods after the completion of treatment varied from 2 weeks32 to 2 years.38

Reported outcomes

There were 7 studies that used a visual analog scale (VAS) to analyze pain levels.16, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 37 In some studies, photography was used to assess the extension of lesions.15, 32, 34, 35, 36, 38, 39 A variety of other indices and parameters were also collected: the plaque index (PI)15, 16, 27; bleeding on probing (BoP)15, 27; the full-mouth plaque score (FMPS)28, 29; the full-mouth bleeding score (FMBS)28, 29; the probing pocket depth (PPD)29; the gingival index (GI)36; the plaque extension index (PEI)36; the mean plaque score (MPS)37; the mucosal index score (MIS)34; the mucosal activity score (MAS)39; the bleeding and soreness of gingiva34; atrophy32; erythema30, 32, 35, 39; desquamation30, 34, 35, 39; the lesion size33; the level of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 1 and MMP-9 in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF)27; the Nikolsky sign34; and the oral health impact profile (OHIP).16

Using all of the gathered data on treatment protocols and reported outcomes, a flowchart was designed to summarize different mucocutaneous diseases (Figure 2). All kinds of treatment are listed in the order of their frequency of use. A code is given to each treatment from “A” to “L” in alphabetical order. From now on, each treatment and its outcomes will be discussed referring only to the codes (A–L) rather than the full names or descriptions. All codes with their complete descriptions are listed below:

A) personal oral hygiene instructions; sonic and manual (soft-bristle) tooth brushing, and interdental cleaning devices;

B) plaque control; SRP and tooth polishing;

C) doxycycline monohydrate; 100 mg, once a day, for 4–11 weeks;

D) alcohol-free chlorhexidine digluconate; 0.2%, 10 mL, twice a day, for 1 week;

E) topical clobetasol; once, twice or thrice a day, for 5 min;

F) clobetasol propionate ointment (0.05% ) in trays; thrice a day for 2 weeks and once a day in the 3rd week;

G) topical 2% fusidic acid ointment; 4 times a day, for 6 weeks;

H) topical fertomcidina-U; 15 min on each jaw, 3 weekly sessions for 12 months;

I) topical 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide; 15 mL, 1-minute rinse, thrice a day;

J) rituximab; 2 infusions of 1,000 mg, with a 2-week interval;

K) topical steroids maintained by self-retaining acrylic labial veneers;

L) tacrolimus or clobetasol; 0.1% and 0.5%, respectively, 2 mL, once a day, for 4 weeks.

Quality assessment

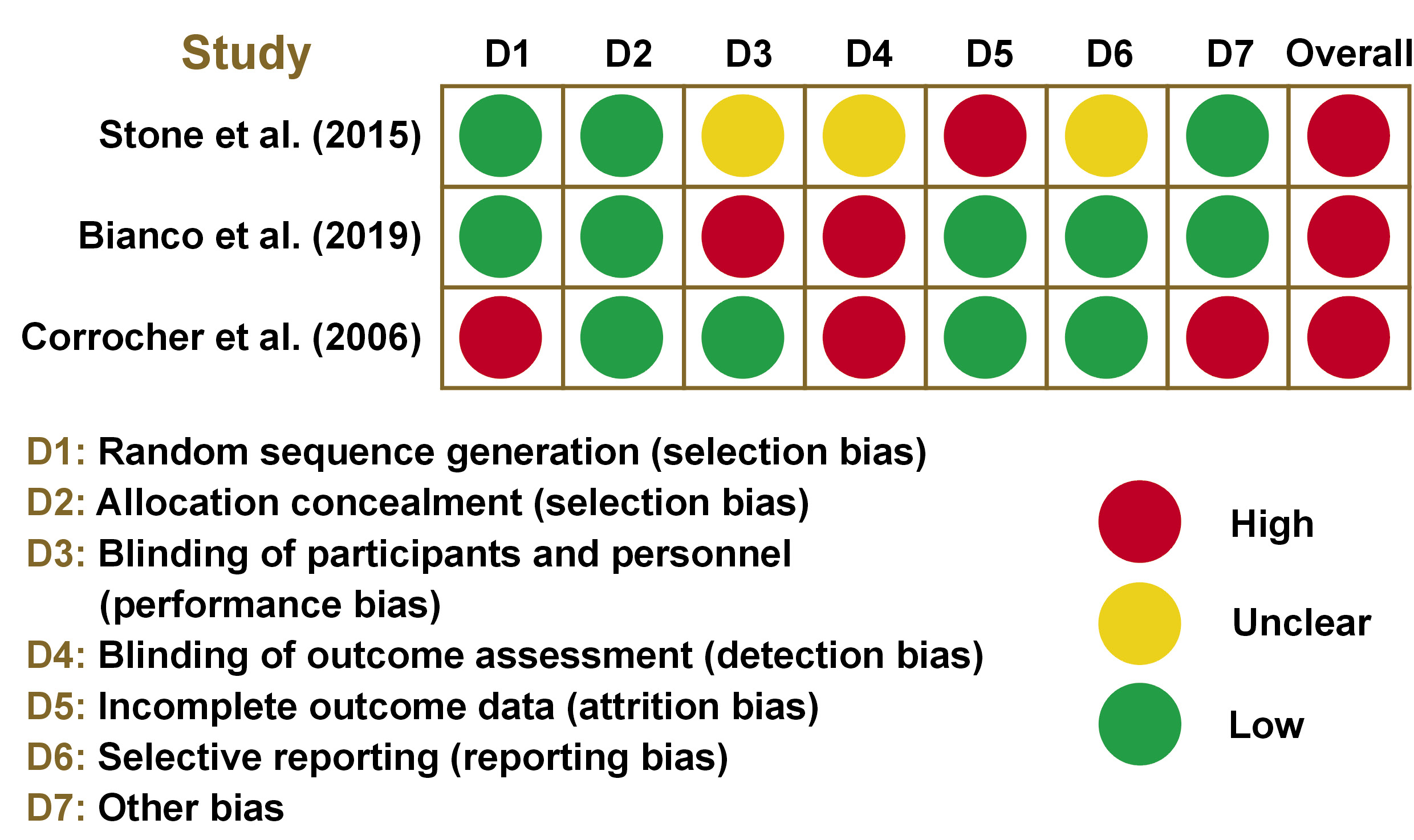

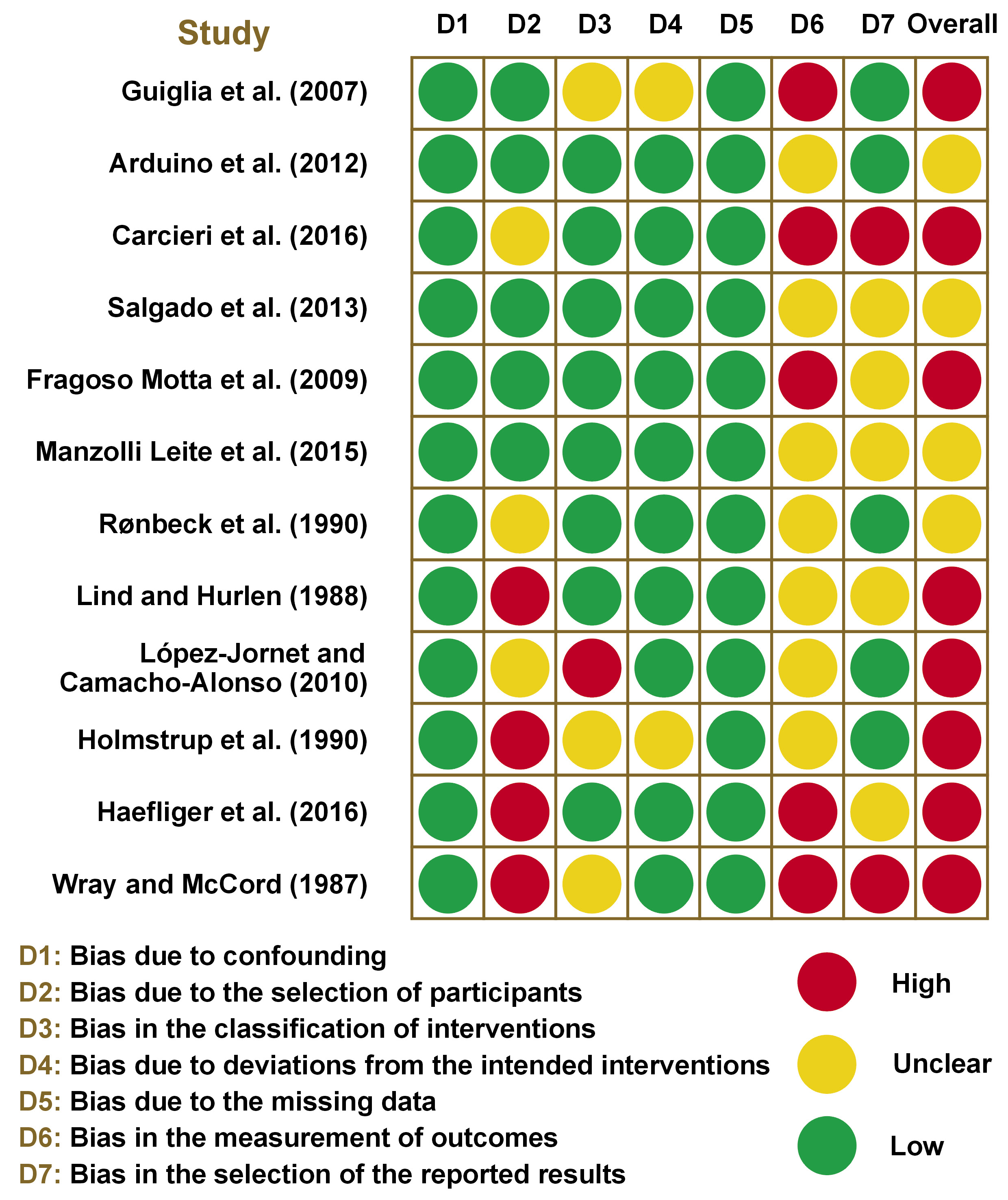

The summary of the risk of bias in randomized and non-randomized studies is displayed in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. All randomized studies had an overall high risk of bias due to an individual high risk of bias in terms of selection,30 performance,27 detection,27, 30 attrition,16 or other bias.30 Among non-randomized studies, 8 studies15, 29, 32, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 had an overall high risk of bias due to an individual high risk of bias in the selection of participants,35, 37, 38, 39 the classification of interventions,36 the measurement of outcomes,15, 29, 32, 38, 39 and the selection of the reported results.29, 39

Discussion

This study was conducted to systematically review the current therapeutic protocols for DG. All of the different mucocutaneous diseases that can cause DG signs and symptoms, and all of the different kinds of treatment for DG are discussed below.

Mucocutaneous diseases

Oral lichen planus

The term “lichen planus” (LP) is a combination of the Greek word “lichen” and the Latin word “planus”, meaning “tree moss” and “flat”, respectively.40 Lichen planus is a chronic immunological, inflammatory disorder affecting hair, skin, nails, and the mucous membrane.41 Oral lichen planus stimulates intractable oral lesions, exhibits chronicity and rarely undergoes self-remission. Oral lichen planus has various clinical manifestations, with DG appearing in almost 10% of cases.42, 43 It is mediated by macrophages, CD8+ T cells and Langerhans cells. Autoimmune mechanisms precipitate apoptosis, causing cell destruction, followed by characteristic histological changes.42 Oral lichen planus is frequently correlated with psychosomatic ailments (e.g., stress, anxiety and depression).44

More than 75% of the participants enrolled in the 15 included studies were diagnosed with OLP as the mucocutaneous disease responsible for DG signs and symptoms.15, 16, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39 The most common treatment for these patients were A, B and C (Figure 2). It could be deduced from the extracted data that proper personal oral hygiene instructions combined with the regular SRP and tooth polishing executed by clinicians resulted in a significant reduction of DG signs and symptoms in OLP patients.15, 16, 27, 31, 36, 37 Topical 2% fusidic acid ointment (G) showed positive results in the longest evaluation period (12 months).33

Mucous membrane pemphigoid

Mucous membrane pemphigus is an autoimmune disease with subepithelial blistering. It is a disease phenotype correlated to one or more disparate anti-basement membrane zone (BMZ) autoantibodies. The hemidesmosome has a variety of components that are targets for the autoantibodies of MMP.45, 46 In a study by Ahmed et al., the age of most MMP patients ranged from 40 to 59 years, and they were mostly women.47 In another study, 35–48% of all DG cases were diagnosed with MMP.2 The most common, if not the only, presentation of MMP is DG.48

In more than 9% of the participants analyzed in this review, DG was related to MMP.28, 29, 32, 33, 34, 35, 38 The only therapeutic protocol that was used in more than one study for MMP patients was doxycycline monohydrate (C) (Figure 2), which showed desirable results in both studies.34, 35 Rituximab (J) had desirable outcomes in the longest evaluation period (6 and 24 months).38

Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune disease distinguished by suprabasilar separation and by acantholysis in the epithelium of the mucous membrane and/or skin. The key target antigen of PV is a component of the desmosome on keratinocytes.49 Pemphigus vulgaris can present at any age. However, PV is most commonly diagnosed in middle-aged and elderly patients.50, 51 Pemphigus vulgaris lesions generally start on the buccal mucosa. Gingival involvement in the form of DG can also be observed.48 If left untreated, PV could be a life-threatening condition.52 It is responsible for 3–15 % of all DG cases.2

The signs and symptoms of DG were caused by PV in almost 6% of all cases in the included studies.29, 32, 33 Each of the 3 studies with the PV diagnosis used a different kind of treatment. However, all of them had one aspect in common – all medications were used topically (F, G, H) (Figure 2). Topical fusidic acid (G) had positive outcomes through the longest evaluation period.33

Plasma cell gingivitis

Plasma cell gingivitis is an unusual benign gingival condition. It is indicated and characterized by the massive and diffuse infiltration of normal plasma cells divided into aggregates by strands of collagen.53 Plasma cell gingivitis is a hypersensitivity reaction to the antigens found in flavoring agents, chewing gum spices, lozenges, and toothpastes.54 The condition causes discomfort, bleeding and severe gingival inflammation.53, 55

Four of the cases in this review were diagnosed with PCG. Topical fertomcidina-U (H) was the only treatment found for DG caused by PCG, resulting in significant improvement in DG signs and symptoms (Figure 2).29

Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme is a penetrating, immune-mediated, mucocutaneous condition, mostly induced by herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections and by certain medications.56 Erythema multiforme lesions initially appear as erythema and edema, and then proceed into superficial erosions and pseudomembrane formations.57 Oral lesions of EM are mainly characterized by the crusting of lips and by the ulceration of non-keratinized mucosa. Hence, EM rarely causes DG.58

Among all of the 330 patients reviewed in this study, only one of them was diagnosed with EM. The treatment used for that patient was doxycycline monohydrate (C), resulting in significant improvement in DG signs and symptoms (Figure 2).34

Non-specified diseases

Corrocher et al. neither declared nor mentioned the diagnosis of their patients (n = 24).30 Rønbeck et al. had 3 cases that they were unable to diagnose.34.We gathered these 27 cases and categorized them as DG associated with NSD. Doxycycline monohydrate (C) and tacrolimus or clobetasol (L) were used for these patients, resulting in significant improvement in DG signs and symptoms (Figure 2).30, 34

Treatment recommendations

It could be inferred that OLP and MMP are the mucocutaneous diseases responsible for most DG cases reported. It is also conceivable that the majority of DG patients, observed and/or treated, are women in their 6th (or higher) decade of life. Some clinicians believe that any DG patient must undergo an initial phase (P1) of personal oral hygiene instructions (e.g., sonic and manual tooth brushing, interdental cleaning devices, and mouthwash) and professional plaque control (e.g., SRP and tooth polishing). If the results of the 1st phase are underwhelming, they enter the 2nd phase of treatment (P2), with different therapeutics. This assumption could be reliable to some degree; most OLP and MMP cases analyzed in this review used personal oral hygiene instructions (A) and professional plaque control (B), followed by desirable results. However, some DG patients (regardless of their diagnoses) have symptoms regardless of their excellent personal oral hygiene routines and regular periodontal visits. These patients are not proper candidates for the initial phase of DG treatment, and should be introduced to/prescribed with different therapeutics. Antibiotics (e.g., doxycycline monohydrate and fusidic acid), antiseptics (e.g., fertomcidina-U), immunosuppressive agents (e.g., tacrolimus), corticosteroids (e.g., clobetasol), and glucocorticoids (e.g., triamcinolone) can all be used for diminishing DG signs and symptoms. Doxycycline monohydrate and topical clobetasol can both be used for DG patients with OLP and MMP. The published data concerning the treatment of DG is not cohesive and convincing enough to turn into a comprehensive guideline. However, relying on the data extracted from the 15 included studies, a step-by-step protocol was proposed to guide clinicians faced with DG patients.

(1) Differential diagnosis of DG: First, make sure that your patient has DG signs and symptoms, and not the symptoms of other similar gingival conditions.

(2) Diagnosis of mucocutaneous disease: Execute all necessary tests and biopsies (if needed) to diagnose the underlying mucocutaneous disease responsible for DG.

(3) Treatment: If the patient was diagnosed with OLP or MMP, a combination of P1 instructions, along with doxycycline monohydrate (general use) or topical clobetasol could be the safest choice. If the patient is affected by PV, PCG or EM, prescribe topical clobetasol, fusidic acid or fertomcidina-U. (Note: Make sure to ask patients about their systemic condition. In the presence of systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus, heart diseases), contact their doctors and ask about the indications/contraindications for the suggested therapeutics.)

(4) Follow-ups: Set monthly follow-ups for 1–2 years. Record the data (e.g., VAS, shedding, erythema, bleeding, and clinical scores) to trace the elimination of DG signs and symptoms.

Limitations

Only 7 of the 15 studies used a VAS questionnaire to record pain levels in their participants. Additionally, the studies mostly did not have a lot in common when it came to selecting different indices and parameters for assessment before and after treatment. Hence, comparing the results and outcomes of the studies was not possible.

We only included studies that had at least 2 patients. By doing this, we had to neglect at least 8 case reports. Therefore, we may have missed out on other possible treatment protocols for DG.

According to our risk of bias assessment (Figure 3 and Figure 4), our included studies had a moderate-to-high risk of bias on average.

Due to the limited number of studies regarding the treatment of DG, we included all different types of studies (e.g., case–control studies, case series, clinical trials, RCTs, etc.). Evidently, not all of the studies had randomization in their selection of participants, and most of the studies had a moderate-to-high risk of bias.

Suggestions

We strongly encourage clinicians to report the outcomes of different treatment protocols used for DG patients. Any additional study can be an important step toward the establishment of sequential treatment protocols as a guideline for the treatment of DG in the future. The moderate-to-high average risk of bias in the included studies shows that in regard to the treatment of DG, we still need many new studies that are conducted carefully, with maximum randomization, to help us develop a better look at different kinds of treatment and their outcomes, with high rates of reliability.

Conclusions

Each DG case requires personalized treatment, depending on the patient’s diagnosis. Most DG cases are caused by OLP and MMP. The safest treatment plan for DG caused by OLP and MMP is personal and professional oral hygiene instructions combined with doxycycline monohydrate or topical clobetasol.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.