Abstract

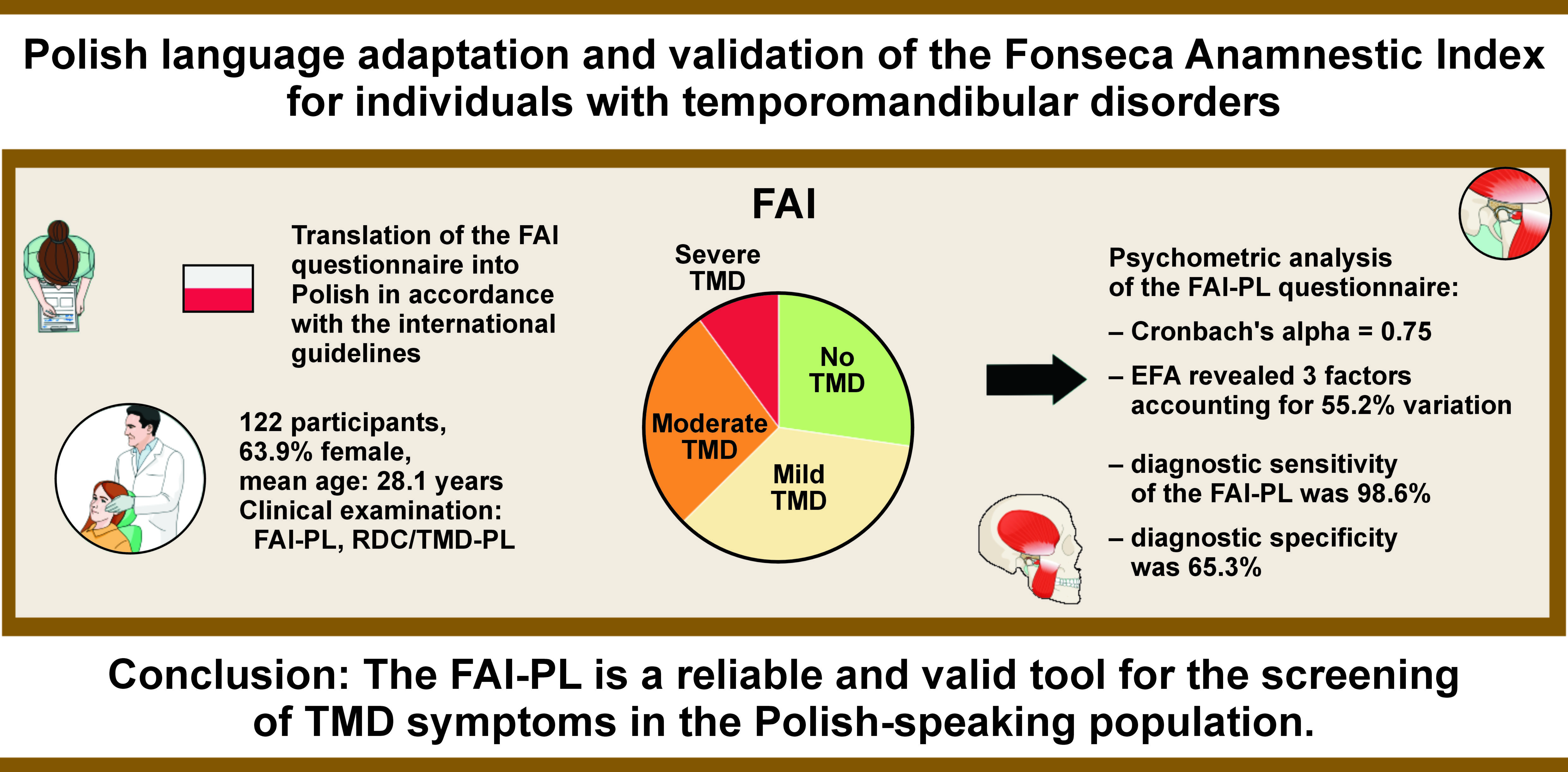

Background. Given the notable prevalence of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) in the Polish population, there is a clear need for the use of simple, reliable questionnaires as screening tools to facilitate the referral of patients to TMD specialists.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to translate and adapt the Fonseca Anamnestic Index (FAI) into Polish and assess its reliability and validity in identifying TMD symptoms.

Material and methods. The Polish adaptation of the FAI (FAI-PL) was developed in accordance with the international guidelines, including the translation and evaluation of the psychometric properties of the questionnaire. Every patient received a standardized assessment, which involved history taking and clinical examination, including the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) and the FAI questionnaire. The psychometric analyses included an evaluation of the questionnaire’s reliability and validity, as well as an exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

Results. Of the 122 individuals enrolled in the study, 63.9% were female. The mean age of the participants was 28.1 years (standard deviation (SD): 6.3). According to the RDC/TMD standards, 40.9% of patients had no TMD, while the FAI assessment indicated that 27% of patients had no TMD. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the FAI-PL was 0.75. The exploratory factor analysis revealed 3 factors, accounting for 55.2% of the total variation. The diagnostic sensitivity of the FAI-PL was 98.6%, while the diagnostic specificity reached a level of 65.3%.

Conclusions. The Polish version of the FAI is a reliable and valid tool for the screening of TMD symptoms in the Polish-speaking population.

Keywords: reliability, validity, translation, temporomandibular disorders, screening

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are a group of clinical conditions involving pain and dysfunction of the temporomandibular joints (TMJs), masticatory muscles and adjacent tissues.1 The data on the Polish young adult population based on the Polish version of the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD-PL) questionnaire indicates a wide range of TMD prevalence, with figures varying from 26.5% to 54.0%.2, 3 Given the elevated occurrence of TMD among young adults, there is a clear need for screening instruments to aid Polish general dentists in referring patients appropriately.

Over the years, numerous questionnaires have been developed to assess the multifaceted aspects of TMD, including the severity and frequency of symptoms, functional limitations, psychosocial impact, and treatment outcomes. These questionnaires are designed to provide standardized, validated and reliable measures to capture the subjective experiences of individuals with TMD.4 One of the primary advantages of using questionnaires in a TMD diagnosis is their ability to gather information directly from the patient. The symptoms of TMD can vary significantly among individuals, and patients’ self-reporting plays a crucial role in understanding the severity, frequency and impact of the symptoms.

The RDC/TMD and the updated version, called the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD), are current references for standardizing the diagnosis of functional disorders of the masticatory system for research purposes.1, 5, 6 The application of standardized diagnostic criteria facilitates the comparison of test results between different countries.7 Nevertheless, the use of the RDC/TMD or DC/TMD for clinical selection and population screening is impractical due to the long history taking and extensive testing procedure. Screening questionnaires for TMD must be inexpensive, short, simple, accurate, and preferably completed by patients.1 It has been documented that TMD have a negative impact on the quality of life, and that initiating treatment leads to an improvement in this area.8, 9

The Fonseca Anamnestic Index (FAI), introduced by Da Fonseca et al. in 1994, is one of the most extensively utilized TMD screening questionnaires.10 It presents a straightforward, cost-effective and efficient patient-reported assessment, indicating the presence and intensity of TMD symptoms.11 Due to its simplicity, quick administration and affordability, the FAI is highly recommended for screening individuals with TMD symptoms.12

To enable effective cross-study comparisons, there is a need for a concise and user-friendly patient-reported instrument that is both reliable and valid for investigating the epidemiology of TMD.

A comprehensive investigation has yet to be conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Polish version of the FAI (FAI-PL). Given this lack of research, the present study had a dual purpose. Firstly, it aimed to translate the FAI into Polish in accordance with the established guidelines proposed by Beaton et al.13 Secondly, the study sought to assess the reliability and evaluate the structural, convergent, content, and face validity of the FAI-PL through a comprehensive statistical analysis.

Material and methods

The minimum sample size was set at 100 participants, based on the recommended ratio of 10 subjects per item in the measurement.14 Participants were recruited from individuals presenting for medical examination and treatment at the Department of Orthodontics and Temporomandibular Disorders at Poznan University of Medical Sciences in Poland. The group consisted of individuals who were seeking either orthodontic assessments or consultations regarding symptoms associated with the masticatory muscles or the TMJ. Individuals aged 18 years and above were eligible to participate in the study. Patients with rheumatoid diseases, individuals who had recently experienced facial trauma, those currently using muscle relaxants and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as well as patients with muscular and neurological disorders were excluded from the study.

All participants underwent a standardized history taking and clinical examination. The patients were examined in accordance with the RDC/TMD-PL Axis I and completed the FAI-PL questionnaire.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland (protocol No. 522/21). Prior to their participation in the study, all participants were duly informed and provided written consent.

Translation

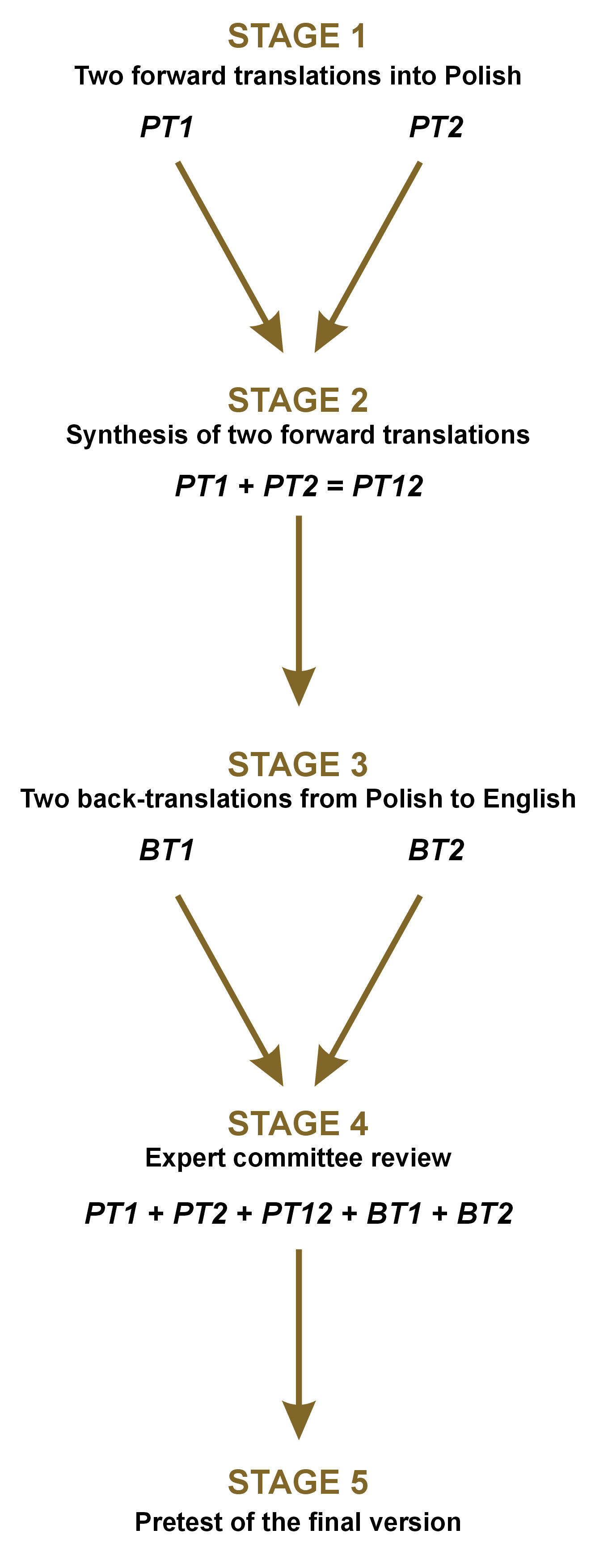

The translation process of the FAI involved 5 stages and adhered to the widely accepted guidelines presented by Beaton et al.13 Initially, the original questionnaire was translated into Polish by 2 independent translators (a TMD specialist (PT1) and an English lecturer (PT2)), both fluent in English and native Polish speakers. Subsequently, a consensus was reached to create an agreed version (PT12). Next, a back-translation from Polish to English was conducted by 2 individuals (BT1, BT2), who were native English speakers and unaware of the original English version of the questionnaire.

Once the translations had been verified, the final version was established. To ensure medical accuracy, a committee of specialists, including a TMD specialist and a general dentist, scrutinized the wording. The entire translation process was supervised by a principal investigator who was not directly involved in the translation process. The test received positive evaluations regarding the clarity of all items, the quality of the language used, its length, and its overall usefulness. Subsequently, the questionnaire was assessed in terms of its ease of completion and comprehensibility within a small sample group (Figure 1). Accordingly, the final version, which did not require any changes after the prefinal test, was employed in subsequent assessments (Table 1).

Measures

Fonseca Anamnestic Index

The FAI is based on the Helkimo Anamnestic Index,15 which consists of 10 closed-ended questions. The possible answers to these questions are “yes,” “sometimes,” or “no,” and the answers are assigned values of 10, 5 and 0, respectively. The maximum possible score is 100. A higher score indicates more severe TMD and a greater severity of symptoms. The following division of the total score is proposed: a score of 0–15 is indicative of no dysfunction; a score of 20–40 indicates mild TMD; a score of 45–60 is indicative of moderate TMD; and a score above 60 indicates severe TMD.

RDC/TMD

Two calibrated TMD specialists conducted a clinical examination of the patients. The examination utilized the RDC/TMD questionnaire, which was translated into Polish by Osiewicz et al.16 This assessment enabled the classification of patients into 3 TMD groups: group I – muscular disorders; group II – disc displacement; group III – arthralgia, osteoarthritis and osteoarthrosis. The study focused on the analysis of Axis I from the questionnaire.

Reliability and validity

The reliability of the FAI-PL questionnaire was evaluated through an examination of its internal consistency, as measured by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, as well as through the application of the test-retest reliability approach. The internal consistency was considered acceptable when the coefficient value exceeded 0.70. The test-retest reliability was evaluated by means of intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), using data from the 30 subjects who retook the FAI-PL after a one-week interval.

Construct validity

The construct validity of the FAI-PL was established through an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Before conducting the EFA, the adequacy of the data was evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. These tests were utilized to assess whether the data was suitable for the EFA. It was assumed that a KMO measure below 0.5 would be a clear signal to stop the EFA. To ensure the strength of the factor loadings, each item was required to have a value of ≥0.40 in order to be included in the final selected factor.

Criterion validity

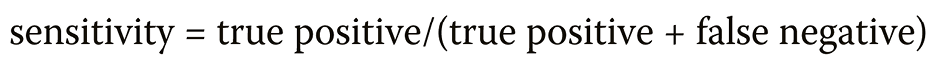

The criterion validity was evaluated, followed by an assessment of the sensitivity and specificity of the FAI-PL in comparison to the RDC/TMD. The sensitivity of the FAI-PL, which represents the ability to identify true positives (i.e., the proportion of TMD individuals correctly identified by the FAI-PL out of the total number of patients with TMD diagnosed by the RDC/TMD), was calculated using the following formula (Equation 1):

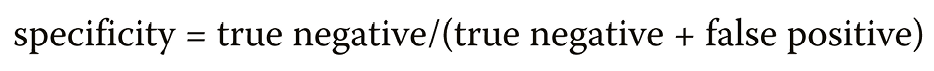

Specificity, which represents the ability to identify true negatives (i.e., the proportion of TMD-free individuals correctly identified by the FAI-PL out of the total number of non-TMD controls established by the RDC/TMD), was calculated using the following formula (Equation 2):

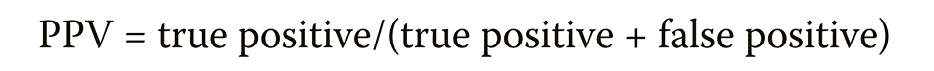

Additionally, positive and negative predictive values were calculated. The positive predictive value (PPV) indicates the percentage of individuals with a positive test outcome who have TMD. It can be calculated using the following formula (Equation 3):

The negative predictive value (NPV) is the probability that subjects with a negative screening test truly do not have TMD. It is calculated as follows (Equation 4):

Statistical analysis

The statistical calculations were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to determine the mean values, standard deviation (SD), and minimum and maximum values of the demographic variables. The normality of the data distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. To assess the differences between independent groups, both the t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test were employed. In all tests, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 122 subjects were recruited for this study. Among all participants, 63.9% were female. The mean age of the patients was 28.1 years (SD: 6.3).

Table 1 presents the distribution of responses to individual queries in the FAI-PL questionnaire. Notably, patients most frequently reported teeth grinding and clenching, with a frequency of 75.4% (combining “yes” and “sometimes” responses). Conversely, the least frequently reported symptom was difficulty moving the jaw to the sides, noted as 18.9% of positive answers.

The results of the FAI assessment indicated that 27.0% of patients had no TMD symptoms, 35.3% demonstrated mild TMD symptoms, 27.0% displayed moderate TMD symptoms, and 10.7% exhibited severe TMD symptoms. According to the clinical examination based on the RDC/TMD questionnaire, 40.8% of participants had no TMD, 36.7% had myogenous disorders (group I RDC/TMD), 7.5% had joint disorders (group II and group III RDC/TMD), and 16.7% had both. These results are presented in Table 2.

Translation

The FAI-PL has been translated with the utmost fidelity to the original. None of the questions in the questionnaire caused major problems in translation.

Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the FAI-PL was 0.75, which indicates satisfactory internal consistency. The corrected item–total correlations, presented in Table 3, ranged from 0.22 (Q9) to 0.59 (Q3). All items met the recommended minimum correlation of 0.20 (Table 3). No items should be excluded from the scale in order to improve the Cronbach’s alpha. The ICCs for the individual items varied from 0.79 to 0.95 and were mostly excellent. These results suggest that the FAI-PL demonstrates high reliability.

Construct validity

The construct validity was determined by the EFA. The KMO test yielded a value of 0.693, while the result of Bartlett’s test was 243.730 (degrees of freedom (df) = 45, p < 0.001). Subsequently, the number of factors for which the value of the statistic, referred to as the eigenvalue, would exceed 1 (Kaiser’s criterion) was determined. As evidenced in Table 4, the data yielded 3 factors and 3 bundles of strongly correlated questions. Those factors explained 55.2% of the total variance observed. Moreover, the factor loadings for all items exceeded 0.40.

The 1st factor consisted of 4 items (Q6, Q7, Q8, Q9), while the 2nd and 3rd factors consisted of 3 items each (Q1, Q2, Q3; and Q4, Q5, Q10, respectively).

Criterion validity

The strength of the agreement between the RDC/TMD and the FAI-PL was moderate, as determined by Cohen’s kappa value of 0.68. The diagnostic sensitivity, defined as the ability of the FAI-PL to detect patients with TMD, was 98.6%. In contrast, the diagnostic specificity, defined as the ability of the FAI-PL to exclude the TMD correctly, was 65.3%. At the same time, the PPV, meaning that the subject had TMD with a positive FAI-PL test result, was 80.9%. Conversely, the NPV was 96.9%, suggesting that a negative test result was highly predictive of the absence of TMD.

Discussion

An accurate and comprehensive assessment of TMD is essential for the diagnosis, treatment planning and evaluation of treatment outcomes. In addition to clinical examination and imaging techniques, questionnaires have emerged as valuable tools for gathering patient-reported information, enabling a more holistic understanding of TMD manifestations.

The aim of this research was to translate the FAI questionnaire into Polish and evaluate its psychometric properties. To date, such an attempt has been made by Glowacki et al.17 However, the study was limited to a cohort of 72 women and lacked a clinical assessment of actual TMD occurrences.17 To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study validating the FAI in a Polish patient population.

The initial phase of the validation process entailed the translation of the FAI into Polish, which represented a pivotal step in the process of questionnaire validation. The translation process aimed to maintain fidelity to the original English version. A subsequent back-translation revealed no notable conceptual deviations from the source material.

With regard to the reliability of the FAI-PL, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was found to be 0.75. The Indonesian version of the questionnaire demonstrated an alpha statistic score of 0.57,18 while the Chinese version by Zhang et al. yielded the score of 0.67.19 The Malay questionnaire achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, and the Turkish version displayed a notably high value of 0.95.20, 21 Consequently, the outcome for the Polish version falls relatively midway when compared to other adaptations, resembling the alpha score reported by Alyessary et al. for the Arabic version (0.77).11 It is vital to underscore that a reliability threshold of at least 0.7 is typically regarded as dependable. The test-retest reliability varied from 0.79 to 0.95 for individual items, with the majority of results falling within the excellent range, which is consistent with the findings of other studies. According to Yap et al., this is likely attributable to the brevity and simplicity of the FAI.20

The EFA revealed a three-factor structure of the FAI-PL. Each of the 3 factors exhibited eigenvalues greater than 1. Principal component analysis demonstrated that these 3 factors explained a satisfactory proportion of the overall variance. The 1st factor includes questions related to the TMJ (TMJ pain, TMJ sounds) and interdental interactions (grinding/clenching, poor occlusion). The 2nd factor is related to jaw mobility (difficulty with jaw movement, mouth opening and jaw fatigue). The 3rd factor covers the remaining questions not directly related to the TMJ and masticatory muscles (including neck pain, headaches and stress). The three-dimensional structure of the FAI has been corroborated in other studies.11, 22, 23 Nonetheless, in each of these studies, different questions were incorporated within the respective factors. The second factor derived from our study (Q1, Q2, Q3) aligns with a factor identified by Alyessary et al. as parafunction-related.11 Similarly, the third factor (Q4, Q5, Q10) corresponds with the second dimension outlined in the study by Rodrigues-Bigaton et al.22 It is noteworthy that the factor analysis conducted by Rodrigues-Bigaton et al. served as the foundation for the development of the Short-Form Fonseca Anamnestic Index (SFAI).24 The SFAI comprises 5 questions extracted from the original FAI questionnaire (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q6, Q7). In contrast, the investigation by Arikan et al. revealed a two-factor structure for the Turkish version of the FAI.21 These factors were categorized as function-comorbidity-related (Q1–Q7) and occlusion-parafunction-psychology-related (Q8–Q10).

Considering the criterion validity, the FAI-PL shows a high degree of agreement with the RDC/TMD Axis I diagnoses. In previous studies, the FAI sensitivity rates ranged from 83.3% to 97.2%.18, 19, 23, 25 In our research, a very high sensitivity rate of 98.6% was achieved. Although the sensitivity was remarkably high, the specificity of the test was considerably lower (65.3%). The results were consistent with those reported by other authors.19, 23, 25 The studies indicate that the FAI demonstrated high sensitivity in identifying individuals with TMD. However, the test’s specificity in distinguishing individuals without TMD in relation to the RDC/TMD or DC/TMD was limited. As Yap et al. have observed, the FAI questionnaire includes a number of questions that are not specific to TMD (neck pain, headache, stress).20 In conclusion of these findings, the FAI can serve as a preliminary tool for evaluating individuals with TMD symptoms and classifying the condition. However, a thorough clinical assessment is essential to ensure an accurate diagnosis following the use of the FAI.25, 26, 27

It is worth noting that the FAI is not the only questionnaire used to screen patients with TMD. Another instrument documented in the literature is the TMD Pain Screener (TPS), which is incorporated into the DC/TMD and the 3 screening questions (3Q/TMD).28, 29 The TPS comprises questions specifically addressing pain, while the 3Q/TMD explores both the occurrence of pain and intra-articular disorders. In screening tests, the latter option is becoming increasingly prevalent.30, 31

Limitations

The findings of the present study are limited by a number of factors. Firstly, it should be noted that the Polish translation was derived from the English version, rather than the original Portuguese text. This may potentially impact the final Polish version of the questionnaire. Secondly, the responsiveness of the FAI-PL was not examined. Further studies are required to assess the impact of the applied treatment on the FAI-PL outcomes. In the present study, the RDC/TMD was employed as the gold standard for diagnosing TMD, given the absence of a validated Polish version of the DC/TMD at the time of article creation.

Conclusions

In summary, the Polish adaptation of the FAI serves as a valuable tool in the diagnosis of TMD, as it effectively captures patient-reported symptoms, functional constraints and psychosocial aspects. Nevertheless, it is essential to use the FAI-PL in conjunction with clinical assessments and imaging procedures to ensure a thorough and precise diagnosis. This assessment demonstrates strong internal consistency, repeatability, and sound construct and criterion validity. In light of these findings, it can be concluded that the FAI-PL is a reliable instrument for use in both clinical settings and research within the Polish context.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland (protocol No. 522/21). Prior to their participation in the study, all participants were duly informed and provided written consent.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.