Abstract

Background. The treatment of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) often includes the management of sleep bruxism (SB) and awake bruxism (AB). However, few studies have investigated how SB and AB change after the initiation of the interventions aimed at reducing the activity of masticatory muscles in TMD patients.

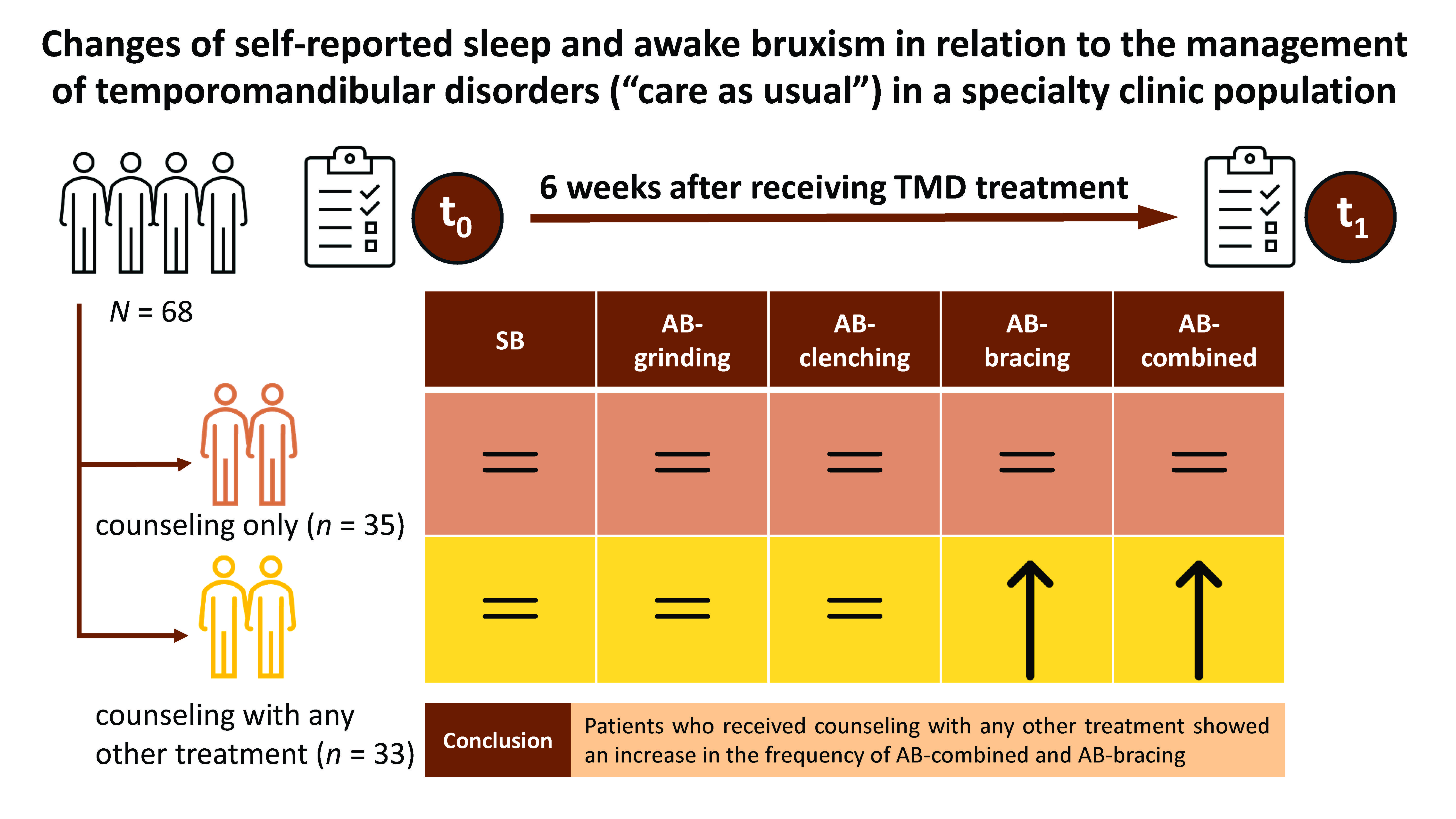

Objectives. The aim of the present study was to investigate changes in self-reported SB and/or AB with regard to baseline at 6 weeks after receiving TMD treatment, i.e., counseling alone or counseling combined with any other treatment, and to investigate the association between the type of TMD treatment and changes in self-reported SB and/or AB.

Material and methods. A total of 68 TMD patients were included in this prospective study, and they all received counseling. Thirty-three of the 68 patients received additional treatment, e.g., physical therapy, psychological therapy and/or an oral appliance, beside counseling. The self-reported SB and AB frequency values were obtained from the Oral Behavior Checklist (OBC) questionnaire at baseline (t0) and at week 6 after receiving treatment (t1). The frequency of SB and AB was assessed as SB, AB-grinding, AB-clenching, AB-bracing, and AB-combined (i.e., the maximum frequency of all AB types combined). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the SB and AB frequency at t0 and t1 in patients who received counseling alone and those who received counseling combined with other treatment. The χ2 test was used to investigate the association between the type of TMD treatment and changes in SB and/or AB.

Results. The frequency of self-reported SB and all types of AB did not change in patients who received counseling only. In contrast, there was a significant increase in the frequency of AB-bracing and AB-combined between t0 and t1 in patients who received counseling combined with other treatment.

Conclusions. No changes in the frequency of self-reported SB and all types of AB were found in patients who received counseling only. However, patients who received counseling combined with other treatment showed a significant increase in the frequency of AB-bracing and AB-combined as compared to baseline.

Keywords: treatment, follow-up, temporomandibular disorders, sleep bruxism, awake bruxism

Introduction

Sleep bruxism (SB) is a masticatory muscle activity during sleep, characterized by rhythmic or non-rhythmic movement, while awake bruxism (AB) is a repetitive masticatory muscle activity during wakefulness, characterized by tooth contact and/or the bracing or thrusting of the lower jaw.1 Bruxism is not considered a disorder, but rather a behavior.1 The prevalence of self-reported SB ranges from 8.0% to 31.4%, while the prevalence of self-reported AB ranges from 22.1% to 31.0% in the general adult population.2 Sleep and awake bruxism have been found to be associated with psychosocial factors, such as stress, depression and anxiety.3 Moreover, SB and AB are often investigated for their association with temporomandibular disorders (TMD). The term ‘temporomandibular disorders’ refers to a group of conditions related to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles and associated structures.4 The prevalence of TMD symptoms in the adult population is 10.3–30.7%.5 Common symptoms of TMD are pain, joint sounds and limited jaw movement.4 The TMD pain has been found to be associated with possible and definite AB.6 A study found that a higher frequency of self-reported AB, including tooth grinding and clenching, and the bracing of the jaw, was associated with painful TMD.7 As for SB, possible SB has been found to be associated with the TMD pain and pain interference with daily life activities,8 but the association between definite SB and the TMD pain is inconsistent.6, 9 Α previous study found that probable sleep and awake bruxism, i.e., SB and AB confirmed via a clinical examination, were associated with pain-related TMD.10 In addition, another study found that 90% of probable sleep bruxers reported jaw-muscle symptoms, such as pain, tiredness or soreness; however, no association was found between muscle activity measured by electromyography (EMG) and jaw-muscle symptoms.11

Temporomandibular disorders constitute a multifactorial condition associated with psychological factors (e.g., stress, depression and anxiety), sleep quality and decreased quality of life (QoL).12, 13 In addition, the pain and fear related to jaw movements have been associated with the decision to seek care for the TMD pain.14 The management of TMD includes multidisciplinary non-invasive treatment, such as counseling, physical therapy, medications, and oral appliance therapy. Invasive treatment, such as TMJ surgery, are less common, and only performed in selected cases.4, 15 The goals of treatment are pain reduction and the recovery of the jaw function.4 Given the longstanding notion that SB and AB are viewed as masticatory muscle activities that can overload the masticatory system and contribute to the persistence of the TMD pain, TMD treatment strategies often involve the management of SB and/or AB.15, 16, 17 Counseling, including education and behavioral modification, can be implemented to reduce AB,18 and has been shown to reduce the TMD pain and improve the jaw function.15, 16, 18 In addition, the awareness of having AB might help reduce pain.16 Sleep bruxism is managed through oral appliances, which aim to reduce the loading of the masticatory system due to the forces exerted while bruxing.19 Biofeedback treatment has been investigated, as it could reduce a jaw muscle activity during sleep,20, 21 as well as during wakefulness,16 but has not yet been implemented as part of routine treatment for the TMD pain.22 Even though SB and AB are common targets in the management of TMD, very few studies have investigated how self-reports of SB and AB change after starting interventions that aim at reducing these masticatory muscle activities in TMD patients.18, 23

The present study aimed to investigate changes in self-reported SB and/or AB with regard to baseline at 6 weeks after receiving TMD treatment, i.e., counseling alone or counseling combined with any other treatment, and to investigate the association between the type of TMD treatment and changes in self-reported SB and/or AB. We hypothesized that changes in self-reported SB and/or AB are associated with the type of TMD treatment. More specifically, we hypothesized that counseling combined with any other treatment may alleviate self-reported SB and AB to a greater extent than counseling alone.

Methods

Study sample

A prospective cohort study was performed in the specialty Clinic for Orofacial Pain and Dysfunction of Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), Amsterdam, the Netherlands, from July 2021 until April 2023.

Patients who were referred to the Clinic for Orofacial Pain and Dysfunction of ACTA were eligible to be enrolled in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria:

– at least 18 years old;

– a diagnosis of the TMD pain and/or dysfunction based on the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD),24 for which treatment would be initiated; and

– signed informed consent.

There was no exclusion for medical or dental reasons. Patients who did not complete the online questionnaire at week 6 after starting treatment (t1) and those who did not receive counseling treatment were excluded.

The study was approved by the ACTA Ethics Committee (ref. No. 2021-64846), and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study procedures

The study comprised 3 phases: baseline (t0); treatment; and follow-up (t1). First, the TMD patients completed a set of questionnaires before their first visit to the clinic. Second, following a clinical examination during the initial visit, the clinicians prescribed treatment based on the DC/TMD diagnosis, relevant comorbidities, patient preferences, and professional judgment. Last, the patients completed an online questionnaire 6 weeks after the start of treatment. Further details regarding the applied materials and methods are provided below.

Baseline (t0)

As part of usual care, all patients completed a set of diagnostic questionnaires before their first visit to the clinic. These questionnaires referred to demographic variables, i.e., age and sex, as well as the average facial pain intensity (the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) questionnaire),25 depression (the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)),26 somatization (the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15)),27 and anxiety (the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)).28 These questionnaires are part of DC/TMD.24 During the patients’ first visit to the clinic, intra- and extraoral inspection, as well as clinical examinations according to DC/TMD were performed. The DC/TMD diagnoses were collected and categorized into 3 categories: pain; dysfunction; and combined pain and dysfunction. The pain category included the DC/TMD diagnoses of local myalgia, myofascial pain, myofascial pain with referral, arthralgia, and headache attributed to TMD. The dysfunction category included the DC/TMD diagnoses of anterior disk displacement with reduction, TMJ subluxation and degenerative joint disease.

Treatment

Each patient received counseling at baseline. The patients received information about their diagnosis and the etiology of their complaints, as well as treatment advice. In addition, the patients could receive one or more other kinds of treatment: physical therapy (including myofeedback, stretching exercises, relaxation, and the self-massage of masticatory muscles); psychological therapy (pain education and a workshop on stress coping); and/or an occlusal splint (a hard occlusal stabilization splint) if the patients reported SB.29, 30 For the purpose of analysis in this study, the type of treatment was categorized into 2 groups: counseling; and counseling with any other treatment.

Follow-up at 6 weeks after starting treatment (t1)

Changes in SB and AB after the start of treatment were assessed during the follow-up period by means of a questionnaire containing 11 questions that evaluated 3 domains, namely pain and dysfunction,31 patient complaints through the patient-specific approach (PSA),32 together with a complaint improvement question, and the frequency of possible SB and AB.33 The patients received the questionnaire through e-mail 6 weeks after their initial visit to the clinic.

The frequency of self-reported SB and AB was assessed with the Oral Behavior Checklist (OBC) questions 1, 3, 4, and 6.33 Self-reported SB was assessed with the OBC question 1, i.e., ‘clench or grind teeth when asleep based on any information you may have’. The 5 answer options were: never; <1 night/month; 1–3 nights/month; 1–3 nights/week; and 4–7 nights/week. Self-reported AB was assessed with the OBC items 3, 4 and 6, i.e., ‘grind teeth together during waking hours’ for the AB-grinding type, ‘clench teeth together during waking hours’ for the AB-clenching type, and ‘hold, tighten or tense muscles without clenching or bringing teeth together’ for the AB-bracing type. The answer options ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The highest frequency among these 3 questions was used as the maximum frequency of all self-reported AB types combined, i.e., AB-combined. In this study, changes in self-reported SB and AB between t0 and t1 were scored as: 1) not improved, if the self-reported SB or AB frequency at t1 was higher than or equal to the frequency at t0; or 2) improved, if the self-reported SB or AB frequency at t1 was lower than the frequency at t0.

Sample size calculation

The G*Power 3.1.9.7 software (https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower)34 was used to calculate the sample size based on the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The power of the study was 80%, and the significance level alpha was 0.05. The effect size was set as 0.5, as we assumed a medium size of difference between the 2 groups. A sample size of 35 patients was required.

Statistical analysis

Age, the average facial pain intensity score, and the depression, somatization and anxiety scores were checked for data distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Baseline characteristics, i.e., age, sex, the TMD diagnosis, the average facial pain intensity, and the depression, somatization and anxiety scores, were compared between the 2 treatment groups using the χ2 test, the Mann–Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test. Differences in the average facial pain intensity and the frequency of self-reported SB and AB, based on the total number of patients, between t0 and t1 were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

To investigate changes in the frequency of self-reported SB and/or AB between t0 and t1 for each type of treatment, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for the patients with counseling alone and separately for those who received counseling combined with other treatment.

To investigate the association between changes in self-reported SB and AB, i.e., improved vs. not improved, on one hand and the type of TMD treatment on the other hand, we used the χ2 test.

The Castor electronic data capture (EDC) program (Ciwit B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands) was used for the collection of study data, and data analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v. 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). This study complies with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

Results

There were 172 patients who met the inclusion criteria at baseline (t0). Of these, 103 patients who did not complete the online questionnaire at week 6 (t1) and 1 patient who did not receive counseling treatment were excluded. In total, 68 patients were included in this study. There was a significant difference in age between the included and excluded patients (p = 0.003). However, there were no significant differences between the included and excluded patients in other baseline characteristics at t0: sex (p = 0.539); the DC/TMD diagnosis (p = 0.441); the average facial pain intensity (p = 0.406); depression (p = 0.979); somatization (p = 0.616); and anxiety (p = 0.702). Among the 68 patients, there were no significant differences in the average facial pain intensity and the frequency of self-reported SB and AB between t0 and t1 (the average facial pain intensity: p = 0.076; SB: p = 0.781; AB-combined: p = 0.180; AB-grinding: p = 0.853; AB-clenching: p = 0.739; and AB-bracing: p = 0.110). The TMD diagnoses in the TMD-pain group included local myalgia (n = 5), myofascial pain (n = 6), myofascial pain with referral (n = 6), arthralgia (n = 7), and headache attributed to TMD (n = 8). In the TMD-dysfunction group, the diagnoses included anterior disk displacement with reduction (n = 6) and TMJ subluxation (n = 2). In the combined group, the diagnoses included local myalgia (n = 16), myofascial pain (n = 9), myofascial pain with referral (n = 16), arthralgia (n = 26), headache attributed to TMD (n = 19), anterior disk displacement with reduction (n = 23), TMJ subluxation (n = 2), and degenerative joint disease (n = 5). Thirty-five of the 68 patients received counseling only, and 33 patients received counseling and other treatment. The types of TMD treatment are shown in Table 1. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the patients provided with counseling alone and those who received counseling combined with other treatment (Table 2).

Among the patients with counseling alone, the frequency of self-reported SB and all types of self-reported AB did not differ between t0 and t1 (Table 3). On the other hand, the frequency of AB-bracing and AB-combined at t1 was significantly increased among the patients with counseling and other treatment as compared to t0 (Table 4).

Table 5 shows a significant association between improvement with regard to AB-combined and the type of TMD treatment (p = 0.023). Specifically, 78.6% of patients who reported the alleviation of AB-combined and 73.3% of patients who reported the alleviation of AB-bracing were the patients who received counseling alone. In other words, the patients who received counseling alone were significantly more likely to show improvement than those with the combined treatment.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate changes in self-reported SB and/or AB with regard to baseline at 6 weeks after receiving TMD treatment, i.e., counseling alone or counseling combined with any other treatment. The results showed that the frequency of self-reported SB and all types of AB did not change in patients who received counseling only. In contrast, in patients who received counseling combined with other treatment, there was a significant increase in the frequency of AB-bracing and AB-combined between baseline and week 6 after receiving treatment. This may imply that patients who received counseling with other kind of treatment became more aware of the presence of AB-combined and AB-bracing after receiving treatment as compared to baseline.

A previous study found that patients who believed that jaw-overuse behaviors like AB might cause jaw pain tended to report a higher frequency of such behaviors as compared to those who believed that there were other reasons for jaw pain.35 In the present study, 63.6% of patients from the counseling and other treatment group received physical therapy, which could indicate that multiple treatment might increase the awareness of having AB in the patients who received such combined treatment. When patients receive multiple treatment, they may recall and recognize more AB events than they did before treatment. Initially, patients may not be aware of their AB until they receive information about it during counseling. Furthermore, repeated exposure to this information through physical or psychological therapy sessions, for example, may increase patients’ awareness of their AB behaviors more than in the case of patients who receive such information only once. Thus, increasing patients’ awareness would be beneficial for bruxism management, especially for AB.36 This is in contrast with a previous study finding that counseling and self-management strategies, like self-relaxation, self-massage, stretching exercises, and warm/cold compresses, reduced masticatory muscle pain and AB activity, as measured by surface EMG in female TMD patients after 8 weeks of treatment.37 Meanwhile, usual-care TMD management did not bring improvement with regard to self-reported SB in a brief (6-week) period as compared to self-reported AB. This is in accordance with a previous study showing that sleep hygiene instruction and relaxation techniques did not reduce SB activity, as measured by polysomnography (PSG), when compared between baseline and 4 weeks after the implementation of these techniques.38 It might be difficult for patients to recognize SB events without a report from their sleep partner. However, the present study shows that usual-care TMD treatment can affect self-reported AB in a brief period.

The present study found that there were differences in the frequency of AB-combined and AB-bracing between baseline and week 6 after receiving treatment in patients who received counseling and other treatment. In addition, it was found that after 6 weeks of receiving treatment, 78.6% of patients who reported the alleviation of AB-combined and 73.3% of patients who reported the alleviation of AB-bracing were the patients who received counseling alone. Notwithstanding, there was no significant association between the improvement of AB-bracing and the type of treatment, but, based on the borderline p-value, it might have some clinical significance. The percentage of the improvement of AB-combined and AB-bracing in the patients with counseling alone was much higher than in the patients with counseling and other treatment: 31.4% vs. 9.1% for AB-combined; and 31.4% vs. 12.1% for AB-bracing. These different percentages may represent some clinical significance, namely that different types of treatment may be associated with the awareness of having AB and the AB-bracing subtype more than SB and other AB subtypes. In the sample size calculation, we focused on the comparison of patients with counseling alone and patients who received counseling with any other treatment between 2 time points. Thus, we required at least 35 patients in each group. However, we had 33 patients in the counseling and other treatment group, which indicates that the sample size might not be sufficient. This small sample size (i.e., insufficient power) may be one of the reasons why the type of treatment was not statistically significant with regard to the improvement of AB-bracing. On the other hand, the frequency of self-reported SB, AB-grinding and AB-clenching was comparable between the patients who received different types of treatment, and between those who improved or did not improve the abovementioned behaviors. Since patients provided with counseling and any other treatment may increase their awareness of AB, they may improve their AB behaviors when we continue monitoring over a longer period than 6 weeks. Future research is needed to investigate this matter.

In this study, there was no significant difference in the average facial pain intensity score between baseline and 6 weeks after receiving treatment. In contrast, a study by Donnarumma et al. showed that counseling and self-management strategies could reduce the TMD pain after 8 weeks of receiving treatment, even though the TMD pain was not significantly different between baseline and at 4 weeks of receiving treatment.37 Similarly, 8 weeks of exercise treatment brought the alleviation of the TMD pain.39 Thus, it is suggested that a longer period than 6 weeks is required to observe a reduction in the TMD pain.

Even though the sample size was small, we noticed some changes between the time the patients received their treatment and before the end of treatment. Despite some unexpected trends observed in this study with regard to changes in AB, it is recommended to apply a questionnaire to monitor changes in TMD complaints and oral behaviors in regular care. It is beneficial to have a standardized protocol to monitor SB, AB, TMD, and psychosocial factors along the treatment process, as we are doing in usual care.

The strength of this study is that, first, we assessed self-reported SB and AB at baseline and at 6 weeks after starting treatment. To the best of our knowledge, no study has observed the effect of TMD treatment over a brief period on changes in self-reported SB and AB. A practice-based research network study found that 96% and 46% of dental practitioners considered an occlusal appliance and occlusal adjustment, respectively, as appropriate bruxism management.40 The present study may encourage clinicians to incorporate other kinds of treatment, like counseling and physical therapy, for patients. Clinicians should inform patients that they may become more aware of their AB activity after receiving physical therapy, and patients should subsequently alleviate their AB activity. Moreover, we used part of the OBC questionnaire to assess self-reported AB, and not only the maximum frequency of AB, but also different aspects of AB activity, i.e., grinding, clenching and jaw bracing.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. First, the frequency of SB and AB was obtained from self-report, whereas the gold standard of SB and AB assessment is PSG for SB and EMG combined with ecological momentary assessment (EMA) for AB.1 Sleep bruxism is reported more frequently when assessed through self-report than with PSG.41 Therefore, using EMG or PSG to assess SB and AB is recommended. In the meantime, the Standardized Tool for the Assessment of Bruxism (STAB) has been developed to assess SB and AB. Using STAB is recommended for future research that would focus on evaluating the bruxism status, the etiology of bruxism and comorbid conditions.42 Second, some patients did not fill out all follow-up questionnaires, which were distributed every 6 weeks after the treatment started. Consequently, we had to include only the 1st follow-up questionnaire. Even though a previous study found that biofeedback could reduce SB and AB events, as measured by EMG, in 3 weeks,43 confirming the cause-and-effect relationship between TMD treatment and SB and/or AB self-reported changes may require a longer period of time. Although 6 weeks is a short period for a longitudinal study, it has clinical relevance as a usual duration for follow-up. Third, we did not measure psychosocial factors after receiving treatment, so we could not monitor changes in the psychosocial status, especially in the patients who received psychological treatment, i.e. in 6 out of the 33 participants who were provided with multiple treatment. Last, due to a small sample size, we did not perform a regression analysis to assess the association between the type of TMD treatment and each type of SB and AB. Future research may require a larger sample size, and should include baseline characteristics for adjustment when assessing these associations.

Conclusions

No changes in the frequency of self-reported SB and all types of AB were found in patients who received counseling only. However, patients who received counseling combined with other treatment showed a significant increase in the frequency of AB-bracing and AB-combined as compared to baseline.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), Amsterdam, the Netherlands (ref. No. 2021-64846). All participants provided signed informed consent.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.