Abstract

Background. There is a well-established link between the use of smokeless tobacco (ST) and the development of oral cancer. This study was conducted to evaluate the impact of tobacco use, quid use, and other adverse habits related to smoking and alcohol consumption on ST-induced localized lesions.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to examine the demographic data, frequency and contact duration of ST on the lesion, as well as to conduct a clinical evaluation of these parameters.

Material and methods. A total of 13,442 patients who had been experiencing oral and dental symptoms for a period of at least 6 months were screened. Of these, 334 patients were diagnosed with ST- or quid-induced localized lesions and had a positive history of ST or quid use. A structured questionnaire was employed to conduct interviews with participants regarding their use of ST and other adverse habits, including smoking and alcohol consumption. Other information related to the use of ST or quid and clinical findings were also recorded, along with the patients’ demographic details. A statistical analysis was carried out using the χ2 test and the regression analysis.

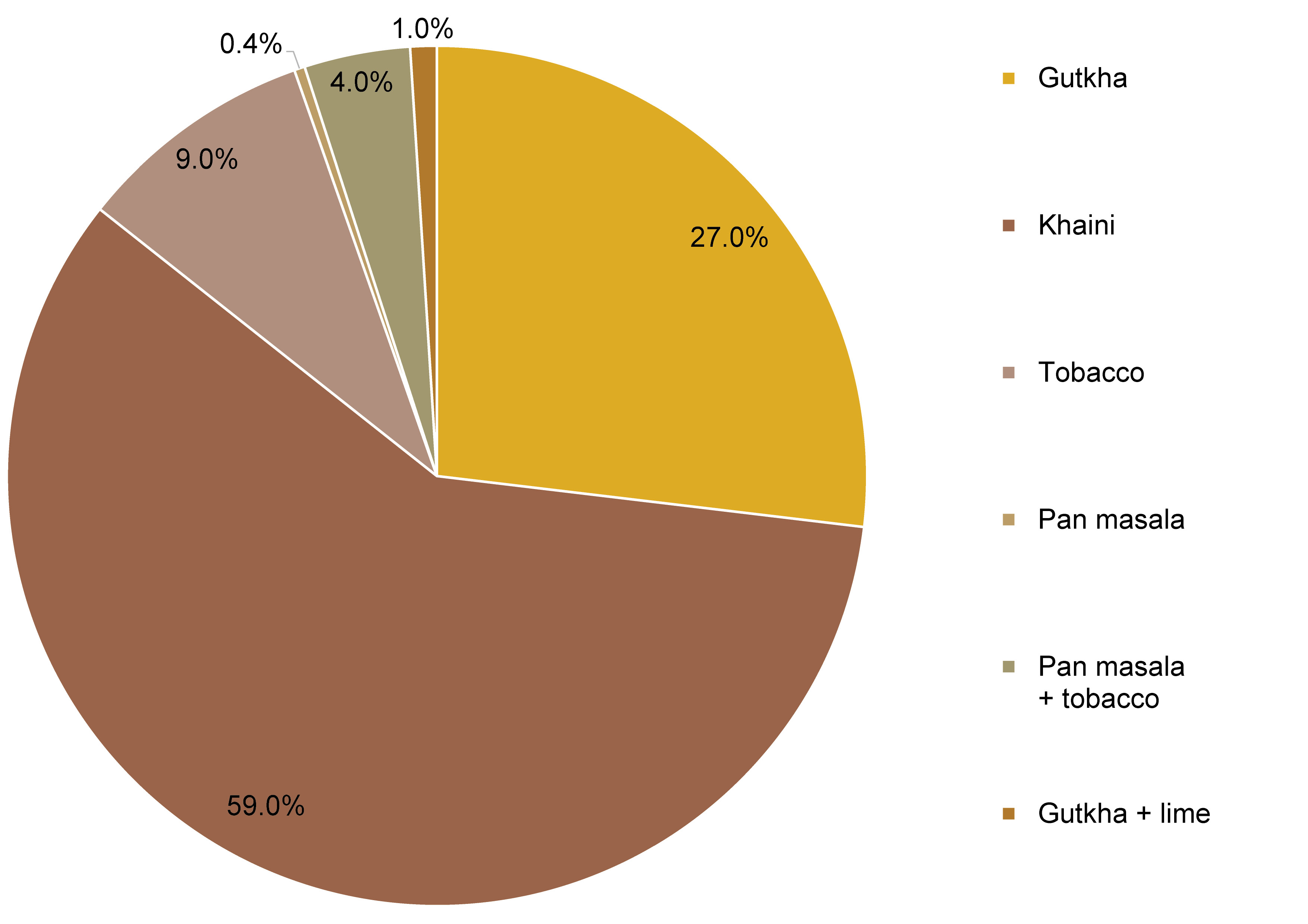

Results. The overall prevalence of ST-induced localized lesions was found to be 2.48%. In the study population, the majority of participants (58.7%) reported a habit of using khaini, while 26.8% reported using gutkha. The study found significant differences in the severity of ST-induced localized lesions and contact duration, frequency of the habit, and the presence of additional habits such as smoking and/or alcohol consumption. Based on this study, we proposed a modified Greer and Poulson’s classification of ST-induced lesions, dividing them into 4 clinical types.

Conclusions. Smokeless tobacco-induced localized lesions frequently remain asymptomatic, with patients unaware of their presence. Other adverse habits, including smoking and alcohol consumption, as well as increased ST contact duration were associated with the development of more severe ST-induced localized lesions.

Keywords: mucosal lesions, snuff, smokeless tobacco, chewing tobacco

Background

Smokeless tobacco (ST) refers to a range of products, including chewing tobacco, snuff, betel quid with tobacco, and paan.1, 2 The use of ST has been associated with the development of oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) and oral cancer. Oral potentially malignant disorders encompass all lesions and conditions exhibiting morphological changes with an increased potential for malignant transformation.3

Tobacco use has been linked to the development of OPMDs, including leukoplakia (white lesions) and erythroplakia (red lesions). Leukoplakia is the initial oral manifestation in over 33% of cases of oral cancer. Thus, white lesions may serve as an early sign for precancerous lesions and should be monitored for an early diagnosis of cancer.4

The high incidence of oral cancer in India reflects the pervasive use of tobacco products.5 In North India, betel quid with tobacco, zarda, gutkha, khaini, and toombak are particularly prevalent and are used by keeping them directly in the buccal and labial vestibules.6, 7 According to Naveen-Kumar et al., 40.64% of patients with oral lesions had a positive history of ST chewing.8 The most commonly used ST includes chewing or spit tobacco in the form of leaves. Spitless tobacco is finely milled and dissolves orally; snuff tobacco is a fine powder. The dry form is inhaled, while the moist form is placed intraorally.9 Quid may be used as a mixture of areca nut, catechu, and slaked lime with tobacco (gutkha) or without tobacco (pan masala).2 Quid is placed intraorally and remains in mucosal contact for a period of time.1 The slaked lime releases an alkaloid and reactive oxygen species from the areca nut, which produces euphoria. From a clinical perspective, ST-associated lesions are less characteristic and differ from those caused by smoking. Smokeless tobacco contains numerous carcinogens, including polonium-210, tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs), volatile aldehydes, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.5 Nicotine, an alkaloid, is primarily responsible for addiction.8 The amount of tobacco used in snuff per day is about 10–15 g. It has been demonstrated that orally absorbed nicotine remains in the blood for a longer period of time.5

Tobacco pouch keratosis (TPK) is also known as snuff dipper’s keratosis or smokeless tobacco keratosis. It is a keratotic mucosal lesion resulting from chronic contact with ST. The mucosal surface affected by ST contact may appear as gray, gray-white, white, translucent, corrugated, or wrinkled. The stretched mucosa may present as a fissured or rippled pouch, which may become leathery or nodular in long-term tobacco users.2 Very few studies have investigated ST-associated localized lesions. The present study sought to evaluate the impact of ST use on the oral cavity. Such lesions can evolve into OPMDs. Thus, early diagnosis and management of ST-associated lesions is essential.

Objectives

The aim of the study was to evaluate the awareness of the lesion, the deleterious effect of the use of a specific type of ST, and the concomitant effect of smoking and alcohol intake on localized ST-associated lesions. The demographic data, including the frequency of use, contact duration, clinical appearance, and prevalence of ST lesions, was analyzed in patients who presented to the outpatient department (OPD) of the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology (Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India). The study provides information about the impact of the usage of different types of ST on the oral mucosa.

Material and methods

Study population

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted at the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology (Faculty of Dentistry, Jamia Millia Islamia, India). The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, Jamia Millia Islamia (approval No. 15/12/50/JMI/IEC/2015), prior to its commencement. The study population consisted of individuals who attended the OPD between February 2016 and July 2016. Both male and female patients aged 15 years and above were considered for inclusion in the study. The sample size was calculated based on the retrospective OPD data from the register. The prevalence of ST-associated localized lesions was found to be 4%, based on the analysis of data from 20 randomly selected days. The sample size was calculated using nMaster software v. 2 (CMC Vellore, Vellore, India). Based on the assumption of a 4% prevalence of TPK in the study population, an absolute precision of 2.5% and a 95% confidence interval (CI), a sample size of 236 was found to be sufficient. The study population included individuals aged 15 and above who had the habit of using ST in any form (khaini, gutkha, paan, spitless tobacco, gutkha with lime, supari with tobacco) and who had been clinically diagnosed with localized tobacco-associated lesions. Only those who provided informed consent for participation in this research and who agreed to the use of the acquired data for research writing purposes were enrolled. Patients who were not willing to consent to participation in the study and those who did not present with ST-associated localized lesions were excluded. A total of 13,442 patients with a range of oral and dental symptoms were screened between February 2016 and July 2016. Patients with a positive history of keeping tobacco quid intraorally were clinically evaluated for the presence of ST- or quid-associated localized lesions. Based on this assessment, a clinical diagnosis of habit-associated lesions was given. The lesions were evaluated in accordance with the Greer and Poulson’s classification.10

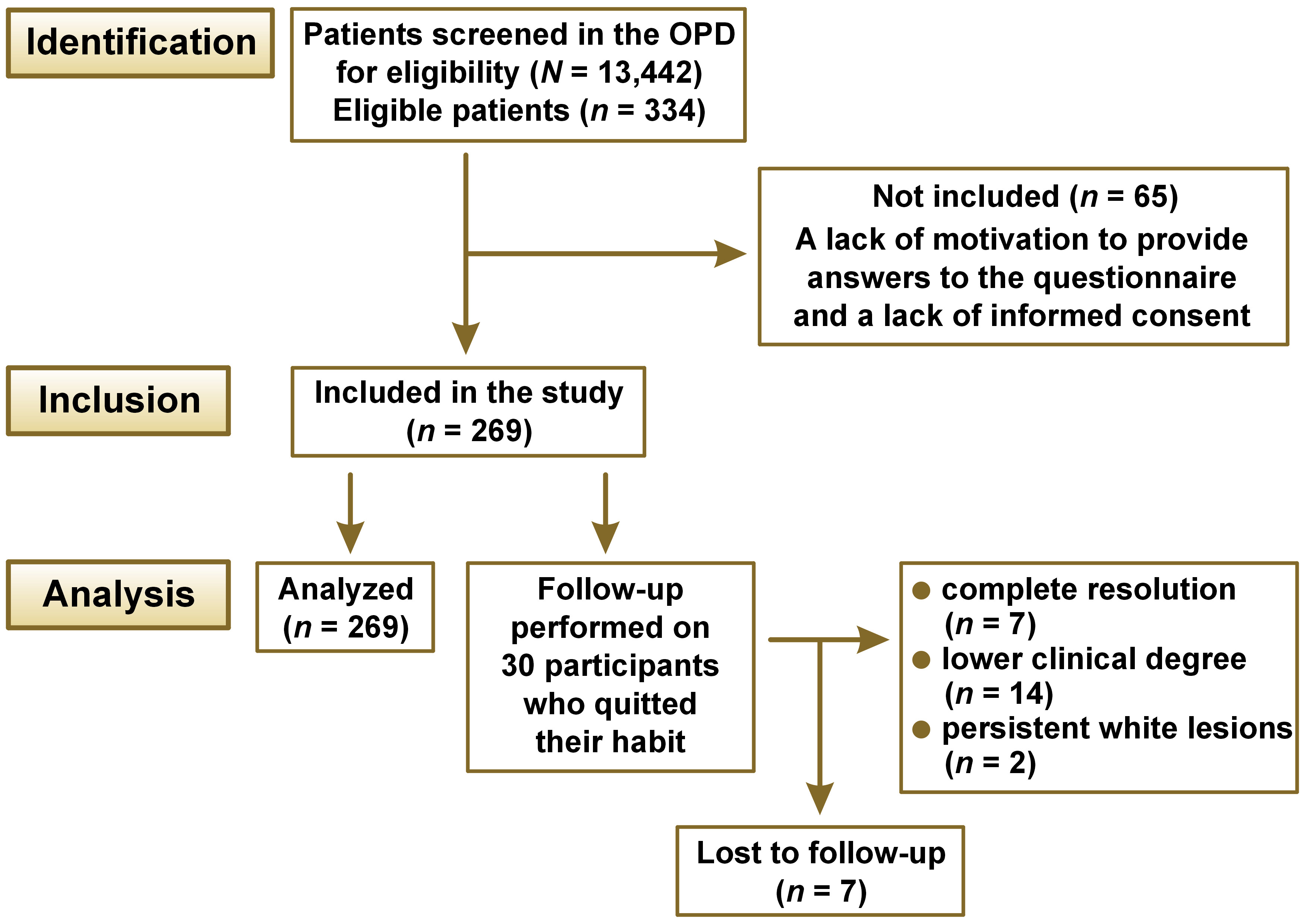

A total of 334 patients were diagnosed clinically with ST-associated lesions. Of these, 269 participants satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study (Figure 1).

Screening program

All individuals who met the eligibility criteria were informed about the nature of the study. A written consent form was provided to each participant after explaining the purpose and process of the research. An intraoral evaluation of the mucosa was conducted using diagnostic instruments and artificial light. The clinical examination of ST-associated localized lesions was performed by trained dental professionals. The screening tool for the diagnosis was based on a clinical evaluation of the lesions in conjunction with a positive history of keeping quid intraorally. The interviewer used a structured questionnaire for the evaluation of ST-related habits and other adverse habits associated with smoking and alcohol consumption. The demographic details, habit-associated history and clinical information were recorded on a proforma. Tobacco pouch keratosis lesions were classified into 3 types according to the Greer and Poulson’s classification system (Table 1).10, 11

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The influence of tobacco type and intraoral lesion grading was evaluated using the χ2 test, with p-values indicating significance at p < 0.05. A binary logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the relationship between various covariates and the staging of ST-associated lesions. The dependent variable, namely the stage of TPK, was dichotomized into 2 categories: stage 1; and stage 2/stage 3. All covariates were adjusted for age and sex.

Results

Age and sex profile of the study population

The age and sex distribution of the total study population revealed that 94.8% of patients were male. The patients were classified into 5 age groups (Table 2). The lowest prevalence of lesions was observed in the 15–20 age group. The remaining age groups showed a prevalence of 23–25%.

Habit profile of the study population

Most of the ST-associated lesions were asymptomatic, and only 12.6% of participants were aware of lesions at the ST contact site. None of the patients reported any oral lesions associated with tobacco quid use. Sixteen percent of the participants reported a burning sensation at the lesion site. All participants had presented for treatment of an additional orodental complaint, and none had previously consulted with a healthcare practitioner regarding lesions at the quid site. The tobacco types were classified into 6 groups (Table 3). The highest number of grade 3 cases reported a history of using khaini. The χ2 test demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between the grading of the lesion and the tobacco type habit (Table 4).

A positive history of smoking was reported by 56.9% of the participants, and 40.9% of patients gave a positive history of alcohol consumption. The χ2 test demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the grading of lesions based on the ST usage, smoking and alcohol consumption. The combination of alcohol consumption, smoking and ST usage was associated with a higher prevalence of grade II and grade III lesions compared to ST-associated lesions (Table 5).

Frequency of ST use

and contact duration profile

Most of the participants reported using quid 1–4 times per day, followed by 5–9 times per day (Table 6). The majority of patients kept quid at the contact site for 5–10 min (Table 7). Most of the participants described their habit duration as 0–5 years, followed by 5–10 years (Table 8). The χ2 test revealed a statistically significant difference between the clinical grading of the lesion and the frequency of ST use, contact time, and the duration of the habit.

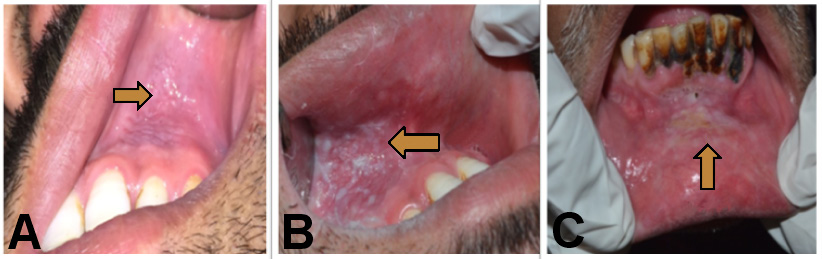

Site of involvement

Smokeless tobacco-associated lesions were observed unilaterally in 69.0% and bilaterally in 21.0% of the participants. Eighty-four percent of cases were seen in the mandibular arch. The highest prevalence of cases was observed on the buccal mucosa, at 88.5%. A single case was reported in the retromolar mucosa, and no cases were identified on the tongue, floor of the mouth, or palatal region. Most of the lesions were present in the left mandibular vestibule (incisor and premolar region). The majority of the lesions were less than 3 cm in size (86.0%). The color of the lesion was white or grayish-white in 84.5% of cases, mixed red and grayish-white in 13.0%, and red in 2.6% of the study sample. The majority of the lesions (88.5%) had ill-defined margins. A total of 36.0% of the grayish-white lesions were scrapable. The lesion could be removed by pulling from the margin of the lesion, leaving an underlying erosive area. A plaque-like appearance was observed in 49.0% of cases, while 11.0% of the lesions showed a corrugated appearance. Tobacco-associated staining was observed adjacent to the dentition in approx. 68.0% of the lesions, and mucosal staining was seen in 34.0% of the lesions. Erythematous changes were present in 15.0% of the cases (Table 9). According to the classification proposed by Greer and Poulson, 59.1% of the participants demonstrated degree 1, 27.9% exhibited degree 2, and 13.0% displayed degree 3 of the lesions (Figure 2). Additionally, hard tissue changes manifesting as brownish discoloration were observed in the adjacent dentition due to the contact with the ST.

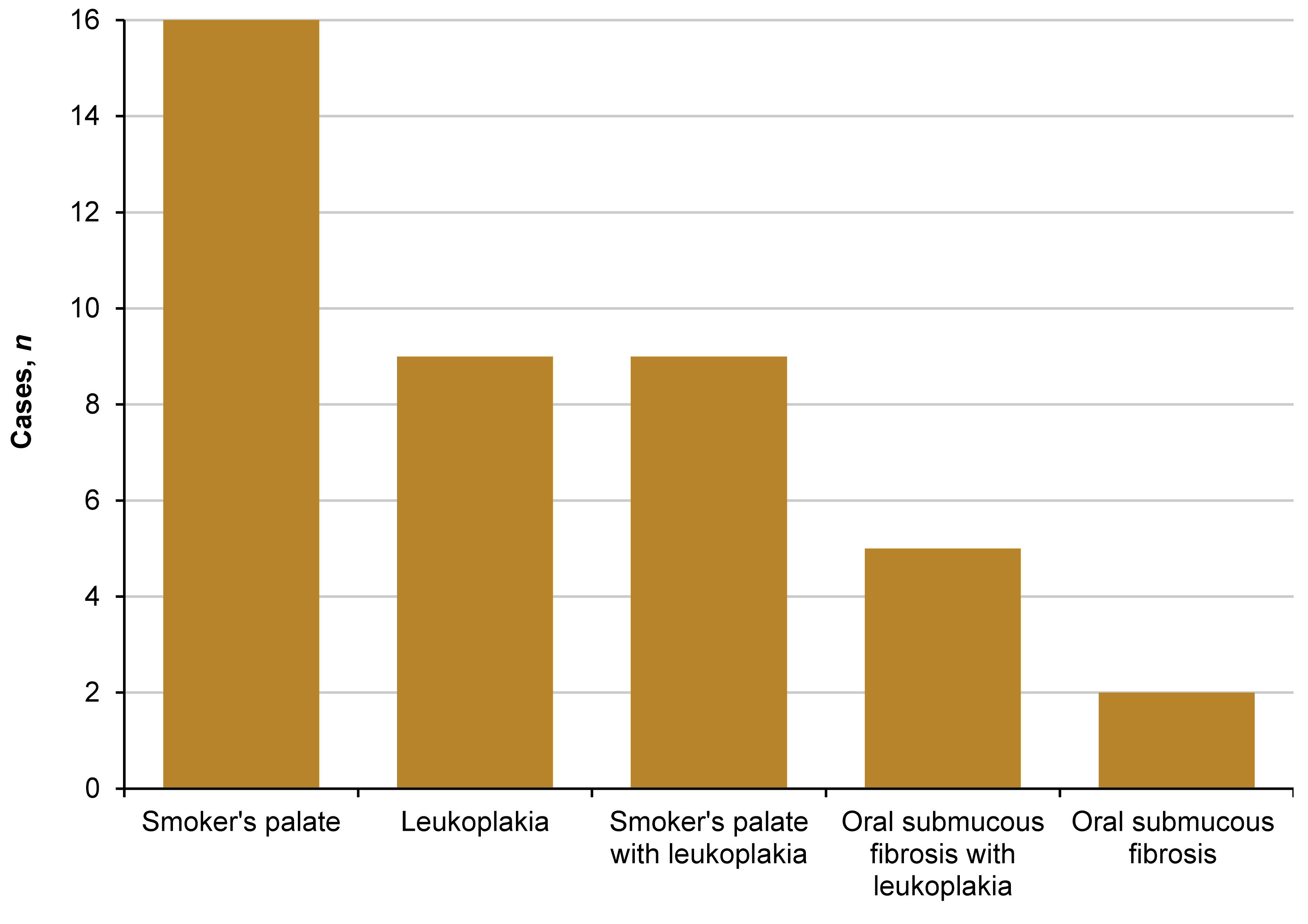

Of the 269 ST-associated lesions, 41 cases exhibited the presence of other tobacco-associated lesions in the following order: 16 were smoker’s palate; 9 were leukoplakia; 9 were leukoplakia with smoker’s palate; 5 were oral submucous fibrosis with leukoplakia; and 2 were oral submucous fibrosis (Figure 3).

A binary logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the association between habit and the staging of the lesion. The dependent variable, namely the stage of TPK, was dichotomized into 2 categories: stage 1; and stage 2/stage 3. All covariates were adjusted for age and sex. With the exception of the type of ST, all covariates were found to have a significant association with the staging of the study lesion. The results indicated that the odds of developing stage 2/3 of the lesion were 3.27 times higher (odds ratio (OR) = 3.270; 95% CI: 1.778–6.014) for a 5–9 times/day frequency of ST usage compared to the lower frequencies. The odds of having stage 2/3 were 7.382 times higher (OR = 7.382; 95% CI: 2.391–22.790) for those with a duration of habit greater than 15 years compared to other habit durations (Table 10).

A total of 30 participants were randomly selected and followed for 6 weeks to observe the effects of quitting the adverse habit. Seven patients were lost to follow-up. The follow-up of the remaining 23 participants demonstrated that in 14 lesions, the clinical severity decreased following a reduction in the habit. Additionally, 7 cases showed complete resolution of the lesions, while 2 cases demonstrated persistence of white lesions at the lesion site even after quitting the habit for 6 weeks (Figure 4,Figure 5).

Discussion

Globally, oral cancer is the 3rd most common cause of mortality in developing countries and the 8th most common cause in developed countries. The use of tobacco is associated with an increased incidence and mortality rate. In 1978, the World Health Organization stated that the appearance of oral cancer is preceded by other lesions, which may show cellular changes that may develop into malignancy.12 Smokeless tobacco in various forms is used in many countries in Southeast Asia.13

Multiple risk factors of leukoplakia have been identified, including genetic factors, local injury, tobacco use, the presence of Candida species, Epstein–Barr virus, sanguinaria, alcohol consumption, and nutritional deficiencies. Recent studies have also demonstrated that the oral cavity is the most common site for drug-induced cancer in the head and neck region. Oral cancer-associated drugs include immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive and chemotherapeutic agents. However, the mechanism by which these drugs induce oral cancer remains unclear. Tobacco use is considered the main etiological factor in the development of oral cancer.14, 15

Tobacco use has been recognized as a risk factor for the development of OPMDs of the oral mucosa, such as leukoplakia and erythroplakia. The prevalence of these conditions among patients attending a hospital in certain areas of India ranges from 2.5% to 8.4%, respectively. The development of cancer has been demonstrated in up to 17% of cases within a mean period of 7 years after diagnosis.16 The term “leukoplakia” refers to a clinical diagnosis, and as this lesion is an OPMD, it should be considered a precancerous lesion.4

Various management options have been considered for OPMDs, including tobacco cessation, antifungal therapy for Candida-associated leukoplakia, retinoids, topical bleomycin, photodynamic therapy, surgical excision, electrocoagulation, cryosurgery, and laser surgery.14

Future treatment options for oral cancer may include the use of different types of extracts from propolis containing ethanol, hexane and their combinations, which showed anticancer activity in tongue cancer cells.17 Other potential management options for oral cancer include polynucleotides, such as graphene oxide–polyethyleneimine, which has been shown to inhibit tumor growth, peptide-based cancer immunotherapy, and antisense oligonucleotides. They reduce the expression of survivin, the factor responsible for the growth of tumors and their resistance to treatment. Furthermore, antisense oligonucleotides increase the apoptotic rate and make the tumor more sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy.18

Smokeless tobacco-associated lesions have been identified as the mucosal lesions most commonly associated with tobacco use. In a study conducted by Joshi and Tailor at Gujarat Hospital in India, 53.1% of cases with an ST habit were identified.19 In a study by Samatha et al., 38.1% of cases were classified as ST-associated lesions.12 Previous studies have shown an increased risk of moderate to severe dysplasia with ST compared to the smoked form, as well as a higher incidence of malignant transformation of leukoplakia due to ST in comparison to the smoked form.13, 20

Tobacco is consumed in a variety of ways, including both smokeless and smoked forms. Previous studies in Scandinavia have demonstrated that moist or loose snuff is the most prevalent form of ST.21, 22, 23 In India, the use of betel quid with tobacco was identified as the most common practice.13, 21 In our study, the most frequently used form of ST was khaini (58.7%), followed by gutkha (26.8%) (Figure 6). This suggests that the prevalence of different ST habits varies depending on region, potentially due to the availability of the ST products. The severity of the lesion is associated with the extent of ST use.22

The occurrence of snuff-induced lesions has been documented in previous studies at a rate of 100% among snuff users.24 In a hospital-based OPD study, the prevalence of ST-associated lesions was found to be 2.4%.19 Our study found a prevalence of 2.48% for ST-associated lesions. Joshi and Tailor reported a higher prevalence of ST-associated lesions in males compared to females.19 In contrast, Samatha et al. found ST-associated lesions to be 24.11 times more prevalent in females compared to males in Nepal.12 In the present study, the sex distribution of the total study population indicated that 94.8% of cases were observed in males and 5.2% of cases were seen in females. The distribution of cases across age groups was nearly uniform, with only a small number of cases observed in the youngest age group (<20 years).

Most of the participants were unaware of the lesion, and only 16.0% of them reported a burning sensation at the contact site. However, they had never visited a physician in relation to this issue.

In our study, the majority of lesions were observed in the left lower arch, which is in accordance with the findings of Bhandarkar et al.7 The left lower arch was more commonly involved (55.7%) than the right side, and the lesions were least commonly seen in the maxillary posterior region (0.7%).12 The buccal mucosa (88.5%) and the vestibular region (71.0%) were the most frequently affected sites. The lesions were predominantly white or grayish-white in appearance (84.5%), with ill-defined margins. The tongue, palate and floor of the mouth were not affected, suggesting a contact-induced alteration in the mucosa. Since the lower vestibule is the most convenient site for keeping the quid, it is unsurprising that it is the most commonly affected region in our study, as reported by Samatha et al.12 In a study conducted in Nepal by Shrestha and Rimal, the labial vestibule and the floor of the mouth were identified as the most affected sites due to ST.23 In our study, ST-associated lesions were observed with high frequency in the mandibular region (84.0%) and unilaterally (69.0%). Gingival recession (GR) localized at the contact site was seen in 42.0% of participants. Bhandarkar et al. revealed that the use of ST was associated with a significantly higher risk of developing GR, with a prevalence of 87.5%.7 The development of recessions is likely attributable to mechanical and/or chemical trauma to the gingiva.7 Previous studies have also suggested an association between ST and GR.21, 23 Additionally, several studies have yielded inconclusive evidence regarding the association between ST and GR.2

Previously, there has been a discrepancy in the terminology used for the classification of ST-associated lesions, as evidenced in studies by Axéll et al., Greer and Poulson, and Tomar and Winn (Table 11).10, 22, 24, 25 These classifications did not mention clinically scrapable features or loose tags of white lesions. Johnson et al. classified quid-induced localized lesions, irrespective of the presence or absence of tobacco in the quid.26 These lesions were considered to be equivalent to snuff-induced lesions at the mucosal contact site.26 Our clinical findings showed the presence of 36.0% of scrapable lesions in degree 2 and 3 lesions, regardless of whether the patient habitually used quid (Figure 7). As there is no uniform definition and terminology for lesions associated with tobacco and quid, we propose a uniform terminology and definition for ST-associated lesions, with the aim of facilitating communication among clinicians (Table 12). Our findings also revealed that a few lesions presented as ST-associated white non-scrapable lesions persisted even after habit cessation and could possibly represent the progression of the lesion to leukoplakia. These persistent white lesions could be diagnosed at the initial visit or after observing their persistence following the cessation of the habit for 6 weeks. A definitive clinical diagnosis of leukoplakia was considered when a negative result was obtained, even after the elimination of suspected etiologic factors, e.g., mechanical irritation, during a follow-up period of 6 weeks.27 Leukoplakia is a classic precursor lesion of oral cancer.28 Such lesions should be managed properly to prevent further severe dysplastic changes.

In our study, 41 participants displayed evidence of additional lesions, attributable to either the smoked or smokeless tobacco form or quid. Many patients reported using other forms of tobacco and quid. It is therefore recommended that a comprehensive history of the patient’s habit of smoking, ST use, as well as their alcohol consumption be obtained. This should be followed by a thorough examination to rule out the presence of other potentially malignant disorders and to determine the optimal course of management for the patient.

Gupta et al. observed an increased incidence of oral squamous cell carcinomas in patients who chewed tobacco.5 Sawyer and Wood also reported an increased risk with an increase in the frequency and duration of the habit.29 In the present study, the logistic regression analysis identified a significant association between increased duration, frequency of the habit and a higher degree of ST-associated localized lesions. A limitation of this study is that only a clinical diagnosis was considered for the ST-associated localized lesions. Further research should include a histopathological diagnosis of the oral lesions. The present study is limited to examining the prevalence and demographic details of a single dental institute. Thus, it is not possible to generalize the findings, and further research is necessary to document such findings on a larger sample size.

Various research studies have shown the role of different biomarkers in the early diagnosis of oral lesions with a poor prognosis. Studies have demonstrated that the elevated expression of biomarkers such as loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at 3p and/or 9p, Podoplanin, p27 loss, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), salivary levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), various interleukins (ILs), osteonectin, and basement membrane protein 40 (BM-40) in oral lesions such as leukoplakia is associated with an increased likelihood of malignant conversion. These markers may be used as an early diagnostic approach for OPMDs.9, 30, 31, 32 Further research should be conducted on the molecular analysis of ST-associated localized lesions, which will provide insight into the malignant potential of such lesions at an early stage. The present study also showed a significant association between the severity of the lesion and the presence of an adverse habit of smoking and/or alcohol consumption. The habit of smoking, when present alone or in conjunction with alcohol consumption and ST usage, was associated with an increased risk of clinically severe lesions. The effect of quitting the habit and a concomitant reversal of ST-associated lesions is in accordance with the findings of Donald et al., who used the term “tobacco pouch keratosis” and recommended the complete cessation of the tobacco chewing habit and a follow-up to assess resolution.9

Conclusions

Oral potentially malignant disorders resulting from an ST habit were mostly asymptomatic at the initial stage. The majority of patients were unaware of the presence of a lesion and thus did not consult a clinician for the condition. The management is more optimistic when ST-associated localized lesions are diagnosed at an early stage. The establishment of uniform terminology, definitions and classifications is essential for effective communication among clinicians. Based on our clinical findings, we propose a modified Greer and Poulson’s definition and classification for ST-associated localized lesions, with the aim of facilitating the understanding of such lesions. The results of our study indicate that an increase in the severity of ST-associated localized lesions is linked to an increase in the frequency and contact duration with the ST or quid, irrespective of the type or form of ST. Additionally, a significant association was observed between the increased clinical stage of the lesion and the additional adverse effects of smoking alone or in conjunction with alcohol. Thus, it is essential that all patients undergo a comprehensive history of adverse habits and regular oral examinations in order to facilitate the early management of ST-associated lesions.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India (approval No. 15/12/50/JMI/IEC/2015), prior to its commencement.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.