Abstract

Background. The correlation between Behçet’s disease (BD) and apical periodontitis (AP) has not been investigated.

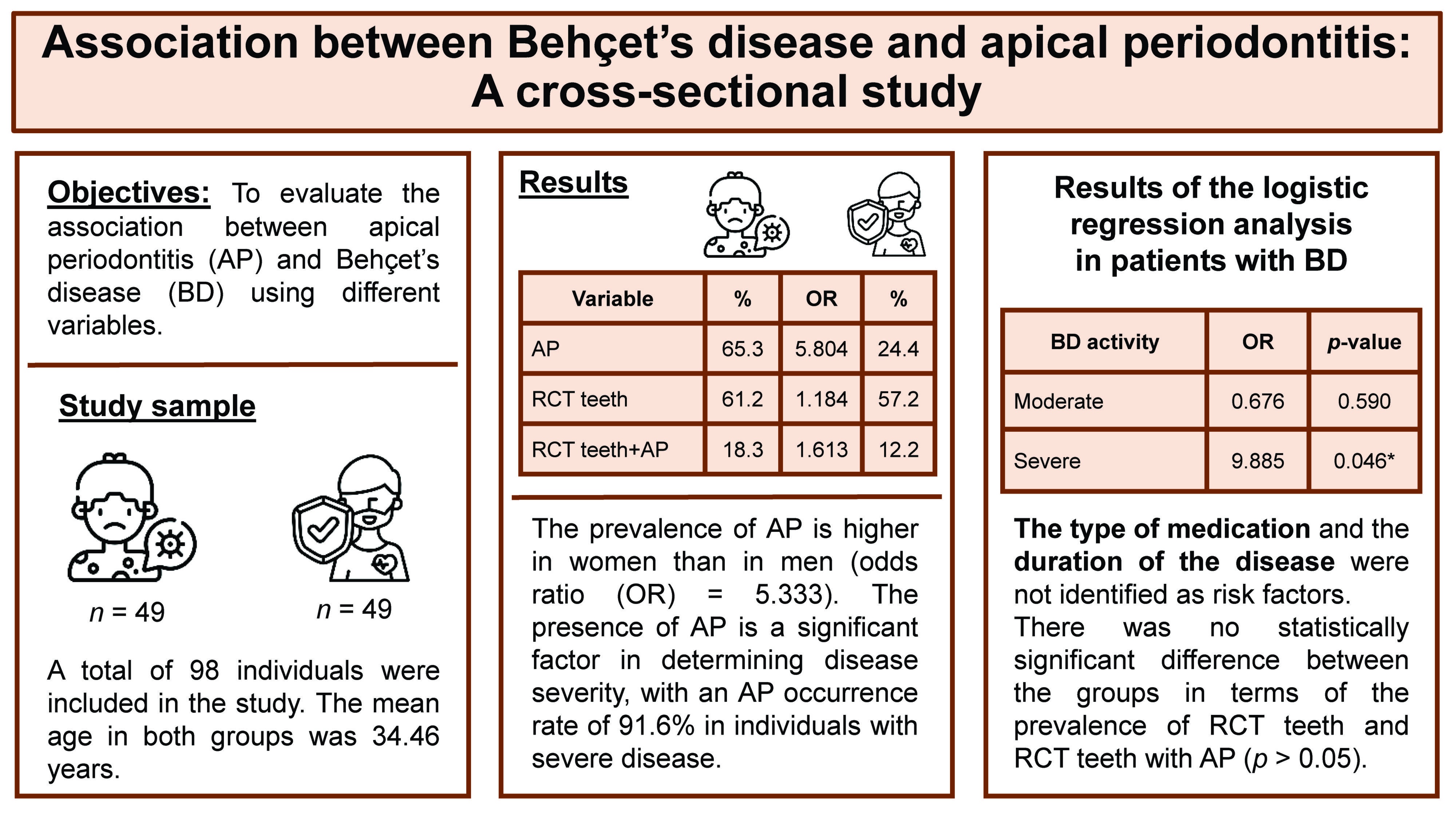

Objectives. The aim of the study was to evaluate the association between BD and AP using different variables.

Material and methods. A total of 98 individuals (49 with BD and 49 controls) were recruited for the study. The presence of AP was confirmed through radiographic and clinical examination in all patients. The following data was evaluated in both the BD group and the control group: the presence of teeth with AP; the presence of root canal-treated (RCT) teeth; the presence of RCT teeth with AP; the severity of the disease; the types of medication taken; and the duration of the disease. The χ2 test and the logistic regression analysis were performed to ascertain the association between BD and AP.

Results. A total of 32 patients in the BD group and 12 patients in the control group presented with AP. The prevalence of teeth with AP was significantly higher in the BD group than in the control group (odds ratio = 5.804, p < 0.05). The χ2 analysis demonstrated a statistically significant association between AP and both gender and BD activity (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the logistic regression analysis indicated that the severity of the disease was a predictor of BD (p < 0.05).

Conclusions. A significantly higher prevalence of AP was observed in patients with BD. However, the success rate of endodontic treatment in patients with BD was comparable to that observed in healthy individuals.

Keywords: Behçet’s disease, Behçet’s syndrome, apical periodontitis

Introduction

Behçet’s disease (BD), also known as Behçet’s syndrome, is a form of multisystemic chronic vasculitis first defined by Dr. Hulusi Behçet in 1937. The disease affects the cardiovascular, nervous and gastrointestinal systems and presents with mucocutaneous lesions. The condition is a triple-symptom complex involving the oral, genital and ocular structures.1 Behçet’s disease affects both female and male individuals across a wide geographic area, but it is more prevalent among people along the so-called Silk Road.2 The causes of BD include immune system disorder, genetic predisposition and endothelial cell dysfunction.3 Since diagnostic tests cannot be performed for BD, the diagnosis is made based on clinical findings.4

Although the pathogenesis of BD is not fully understood, studies have demonstrated that immunological dysregulation plays an important role in its etiology and progression. An important part of the immunopathogenesis of BD is a T cell-mediated immune response.5 T cells are divided into 2 groups, known as T helper cells 1 (Th1) and T helper cells 2 (Th2), which have antigen-specific receptors on their cell membranes for the identification of pathogens.6 One of the key pathological immune characteristics of BD is the presence of elevated levels of pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines (interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-12, IL-18, IL-27 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)) and Th2 cytokines (IL-2, IL-10, IL13, and tumor necrosis factor-β (TNF-β)), which play crucial roles in the disease.7, 8 It has been demonstrated that IL-6 is the main cytokine that functions as a promoter in patients with BD.9, 10 Furthermore, IL-6 and TNF provide both local and systemic responses to pathological stimuli.11

In the event of pulp necrosis, bacteria and their by-products reach the periradicular tissues via the apical foramen and lateral canals, thereby triggering inflammatory and immunologic reactions and causing apical periodontitis (AP).12 T cells are one of the key factors involved in AP.13 They produce cytokines, which may stimulate bone destruction and exert a pro-inflammatory function in AP.13 The progression of AP and the subsequent bone resorption have been attributed to a response in Th1.8

Arabaci et al. indicated that periodontal status is influenced by the presence and severity of BD.14 Another study demonstrated a correlation between periodontitis and BD activity.15 Since AP and BD involve similar destructive and inflammatory reactions, there is a possibility of an association between the two. Thus, this cross-sectional study aimed to evaluate the correlation between BD and AP. The null hypothesis was that no association would be observed.

Material and methods

This study conforms to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. The clinical study was conducted in the Department of Rheumatology, School of Medicine, and the Department of Endodontics, Faculty of Dentistry (Atatürk University, Erzurum, Turkey). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Atatürk University (decision No. 71-09/2022). The sample size was calculated based on the data from a previous study,16 with an effect size of 0.35, an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of 0.9. According to this analysis, the study should have included 85 patients.

The study population consisted of 49 patients with BD, aged 28–65 years, who were accepted for treatment at the endodontics clinic. The patients did not present with any additional systemic diseases apart from BD. The participants of the study met the criteria set forth by the International Study Group for BD.17 The control group consisted of 49 sex- and age-matched patients who did not have any systemic diseases.

The BD activity index was used to determine the severity of the disease, with patients classified accordingly.18 Each symptom was assigned a specific score. The overall disease activity was determined by summing the scores. Oral aphthous ulcers, arthralgia, genital ulcers, erythema nodosum, folliculitis, and papulopustular lesions were classified as mild symptoms and were assigned 1 point each. Moderate symptoms included arthritis, deep vein thrombosis of the legs, anterior uveitis, and gastrointestinal involvement. They were assigned 2 points each. Posterior uveitis/panuveitis, retinal vasculitis, arterial thrombosis, neuro-Behçet’s disease, and bowel perforations were classified as severe symptoms and were assigned 3 points each.

Additionally, the duration of the disease and the types of medication administered were documented. The types of medication were scored as follows: a score of 1 was assigned to colchicine; 2 to anti-TNF; 3 to steroids; and 4 to immunosuppressive drugs. If a patient was taking 2 or more medications, the highest score was assigned to the type of medication.

The diagnosis of AP was confirmed by clinical and radiographic examinations. All types of AP, including asymptomatic AP, symptomatic AP, acute apical abscess, and chronic apical abscess were considered. All radiographic images were obtained using the same imaging system (Planmeca Promax; Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland). If the periapical tissue was normal or had minimal changes in bone structure, the related tooth was classified as healthy (PAI 1 and 2), according to the periapical index (PAI).19 In the event of a lost periodontal ligament or periodontitis with exacerbating features (PAI 3, 4 and 5), the tooth was classified with a periapical pathology.20 The PAI score for multi-rooted teeth was determined based on the highest score observed across all roots.21

Digital panoramic radiographs were taken and analyzed by an endodontist and an experienced dentist (Figure 1,Figure 2). Both observers were blinded to the study groups. In cases of disagreement, the analysis was repeated. After the radiographic analysis, pulp sensitivity, percussion and palpation tests were performed to confirm the clinical diagnosis of AP. Patients with at least 1 tooth exhibiting signs of AP were included in the AP group.

The following data was recorded for all patients: the number of patients with AP; the number of patients with root canal-treated (RCT) teeth; and the number of patients with RCT teeth and AP.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The χ2 test was performed to determine the differences between the BD group and the control group. A univariate analysis of potential predictors of BD and AP, as well as RCT teeth and RCT teeth with AP, was carried out using the Mann–Whitney U test. Furthermore, a model was constructed for the logistic regression analysis to better understand the relationship between cases with BD and AP, RCT teeth, and RCT teeth with AP. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 98 individuals with 2,051 teeth (1,026 in the BD group and 1,025 in the control group) were evaluated. While 32 patients were diagnosed with AP in the BD group, only 12 patients were diagnosed with AP in the control group. The prevalence of AP was significantly higher in the BD group (65.3%) compared to the control group (24.4%) (odds ratio = 5.804, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

At least 1 RCT tooth was found in 30 (61.2%) and 28 (57.2%) patients in the BD and control groups, respectively. The observed difference in the number of RCT teeth between the BD and control groups was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). At least 1 RCT tooth with AP was identified in 9 (18.3%) and 6 (12.2%) BD and control patients, respectively. The difference between the groups in terms of the presence of RCT teeth with AP was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

The intragroup analysis revealed a higher prevalence of AP in male BD patients compared to female patients (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Additionally, the prevalence of patients with AP was significantly higher in the severe group than in the mild and moderate groups (p < 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference between the mild and moderate groups in terms of the AP prevalence (p > 0.05). No statistically significant difference was observed in terms of age, the duration of the disease, or the type of medication among patients with BD (p > 0.05). To better understand the relative influence of the predictors, a logistic regression analysis was performed (Table 3). The constructed model demonstrated that BD activity was a predictor of AP (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Systemic disorders can be regarded as modulating factors affecting the progression of an oral infection, rather than etiologic factors.22, 23 The success of root canal treatment is adversely affected in individuals with diabetes and hypertension.24 Costa et al. revealed that individuals with cardiovascular diseases are more prone to endodontic pathologies.25 Moreover, patients who had undergone kidney transplantation exhibited a higher prevalence of endodontic pathology compared to healthy individuals.26 However, this is the first study investigating the relationship between AP and BD based on a range of variables.

Apical periodontitis is associated with an elevated level of cytokines and inflammatory mediators secreted by T cells, including IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α.27 In addition, the presence of CD57-positive cells in all cases of chronic AP suggests that activated natural killer (NK) cells contribute to the progression of periapical pathologies.28 Natural killer cells can release cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF.29 The bone destruction process in periradicular pathology is regulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α.30 Th1 cells are mainly effective in the pathogenesis of BD. It has been shown that Th1 cells and cytokines are significantly elevated in individuals with active BD.31 Interleukin-1, IL-6 and TNF-α are the main cytokines observed in BD patients.32 Hasan et al. have confirmed the association between NK cells and BD and identified a reduction in NK cells in the peripheral blood of active BD patients.33 The depletion of NK cells in the peripheral blood of BD patients may reflect an increased homing of these cytotoxic cells to inflammatory sites.5 Additionally, increased levels of IFN-γ, which are secreted by NK cells, have been reported in individuals with active BD.31 Therefore, the association between the 2 diseases can be attributed to increased cytokine similarity and the impact of these cytokines on disease progression in both AP and BD.

The present study indicates that the prevalence of AP was higher in male individuals in the BD group. While BD has an impact on both genders, it is more severe among young males.34, 35, 36 The relevant clinical difference between men and women is unclear, but it may be related to hormonal factors, such as testosterone and prolactin.37, 38

Despite the lack of consensus on a treatment program, colchicine, corticosteroids, anti-TNF agents, and cyclosporine have been demonstrated to effectively control BD symptoms.39 Drug therapy provides symptom control, reduces inflammation, supports the immune system, provides remission, and increases the patient’s quality of life.40 However, our study did not identify an association between AP and the type of medication used to treat BD. Since no other study has investigated the possible associations between the type of medication and AP, a direct comparison cannot be made.

The study results indicated that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups with regard to the prevalence of RCT teeth and those with RCT teeth and AP. In other words, BD did not affect the maintenance of endodontic treatment. Bone destruction in AP has been related to the Th1 response, which leads to the activation of osteoclasts.41 The administration of intracanal medication during endodontic treatment can result in successful outcomes, as evidenced by a previous study which indicated that intracanal medication can reduce the levels of cytokines involved in AP.42

A limitation of this study is the absence of data regarding the patient’s oral hygiene. Oral hygiene may influence the prevalence of AP. Previous research has shown that the incidence of AP is higher among patients with periodontal disease (PD) compared to those without PD.43 Another study has reported that dental caries and PD were the most prevalent oral health concerns in individuals with rheumatic diseases (73.1%).44 These dental problems could be attributed to the side effects of medications.45 Another limitation of the present study is that it was based on an observational cross-sectional design, which only captured data at a single point in time. However, the results of the present study provide baseline information for prospective studies with larger sample sizes. Finally, further controlled clinical trials are required to elucidate the role of AP in BD.

Conclusions

Behçet’s disease was shown to be significantly associated with an increased prevalence of AP. It can be concluded that, among all variables, BD activity was the most effective predictor of AP. Individuals with severe BD may be more prone to developing AP in comparison to those with mild and moderate BD activity. No statistically significant difference was observed regarding the prevalence of RCT teeth with AP between the BD and control groups. Thus, it can be concluded that BD did not affect the success rate of root canal treatment. Further prospective studies are required to confirm the relationship between BD and AP.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Atatürk University (decision No. 71-09/2022).

Data availability

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study is included in this published article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.