Abstract

The aim of this proposal is to (1) review the current literature, (2) shed light on the importance of creating universally accepted guidelines, (3) provide help and guidance in the decision-making process with regard to the removal of mandibular third molars (M3Ms), and (4) reduce the risk of exposing the patient to unnecessary harm and complications due to the inappropriate removal or retention of M3Ms.

It is obvious that the indications for the extraction of M3Ms will continue to be an area of controversy and strong debate. The evidence for or against prophylactic extraction is ambivalent; there is evidence to accept or reject the stance against prophylactic extraction in some specific cases, and there are published articles to support both opposing views. The available guidelines on the extraction of third molars are limited in number, and are mostly tailored to fit specific settings or countries. There are no available guidelines that might be widely used to help in the decision-making process for the international community. We hope this proposal will constitute an important first step toward creating universally accepted guidance.

Keywords: prophylactic removal, third molar surgery, dental extraction, impacted third molars, impacted wisdom teeth

Introduction

Third molars usually erupt at the age of 17–26 years,1, 2, 3 and can cause significant problems both in the short and long term. The eruption process can generally follow one of 2 distinct patterns – impacted (vertical, mesial, distal, horizontal, or transverse) or non-impacted (fully erupted). Although both impacted and non-impacted mandibular third molars (M3Ms) can be asymptomatic and disease-free, their eruption can sometimes be associated with significant pain, inflammation, swelling, difficulties in mastication, limited mouth opening, and/or acute pericoronitis. In some cases, these pathologies may be significant enough to cause considerable discomfort and facial swelling, thereby contributing to morbidity in the affected individuals.

Furthermore, both impacted and non-impacted M3Ms can be associated with dental-related pathologies, such as tumors, cysts, caries, and/or periodontal disease, which may not be limited to third molars, but also affect the adjacent tissues and teeth. All of these factors may indicate the need for the removal of M3Ms.4

Some clinicians and patients have long held the notion that M3Ms may be prophylactically removed to avoid the potential pathologies arising from their impaction. However, many healthcare systems do not agree with the assertion that lower third molars should be removed in the absence of an overt pathology or other clinical justification.5

Currently, there is limited data available to estimate how many healthy and asymptomatic M3Ms have been removed without justification. However, it is believed that in the past, up to 44% of healthy wisdom teeth were inappropriately removed in the UK.6

There are varying approaches to the management of M3Ms, leading to the creation of clinical guidelines in this regard, especially in the UK. However, these and similar clinical guidelines are often criticized, amended, or even withdrawn due to the lack of consensus on their appropriateness. Despite these varied recommendations, the prophylactic removal of M3Ms is still routinely undertaken and accepted in many parts of the world.7 Given these diverse recommendations and concerns about the management of M3Ms, an evidence-based approach that would benefit clinicians and patients alike is highly desirable. The management of M3Ms may remain controversial with differing opinions, but the aim of this proposal is to emphasize the importance of creating universally accepted guidelines. We hope this proposal will constitute an important first step toward creating such guidelines.

Methodology

While conducting the review, the following databases were electronically searched up to January 2023: MEDLINE; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); PubMed; Google Scholar; and the Cochrane Library. A hand search of the reference lists of the included articles was also conducted. The search was restricted to articles published in English. After removing duplicates, the search yielded 486 articles, but only 12 guidelines and position statements were identified.

Available guidelines

The M3M is an unpredictable tooth in terms of development and clinical presentation. As such, it is not surprising that the available guidelines on its management are limited in number. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) released clinical guidance in 2000, recommending that asymptomatic impacted M3Ms should not be removed, and only those with a defined pathology should be considered.6 The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) also issued guidance on the management of impacted, unerupted M3Ms; however, the guidance was withdrawn in 2015.8

In the USA, in 2016, the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) issued a white paper on the management of M3Ms.9 Aside from this, there is very little guidance comparable to that released in the UK. The paper is a position statement on the management of third molars rather than actual guidelines. The white paper strongly recommends thorough evaluation by a surgeon, with the trend in the USA leaning toward removing the third molar in young individuals, even if the tooth is healthy and asymptomatic.9 Consequently, the position statement from AAOMS has not been without criticism.6, 10, 11

In 2014, the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim published guidelines recommending the prophylactic removal of asymptomatic and disease-free M3Ms in specific situations to avoid possible future complications, such as injury to the inferior alveolar nerve, pericoronitis, postoperative bone defects, visible plaque in the adjacent teeth, or dental caries.7 However, there are 2 contraindications to such intervention: 1) if the asymptomatic unerupted M3M is healthy and completely covered by bone; and 2) if the removal could pose a significant or unreasonable risk to the patient’s health.7

Given the contrasting opinions on the subject, a Cochrane review aimed to clarify the evidence on the prophylactic removal of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth vs. the retention of the tooth.3 The review concluded that the evidence either supporting or refuting the routine prophylactic removal of asymptomatic healthy impacted third molars was insufficient.3

It is apparent that the management of impacted M3Ms varies considerably, despite all the available guidelines being based on the same available evidence. These differences seem to be influenced by several factors, including resources, environment, surgical trends, culture, reimbursement by insurance companies, and government actions.7 For instance, in the UK, the surgical removal of impacted third molar teeth is funded by the National Health Service (NHS). In 1990, approx. £30 million was spent by NHS on this procedure; similarly, in the private sector, approx. £22 million was spent in the same year.12, 13, 14 Therefore, it is suggested that the prophylactic removal of M3Ms contributes significantly to increased healthcare costs that could potentially be utilized for other healthcare needs. The potential cost savings could be considerable, since there is no evidence that retaining healthy and impacted M3Ms leads to unmanageable symptoms, pathologies or serious consequences for the patient.3

Given the issues related to this topic, it is important to use an evidence-based approach to evaluate the risks inherent in the retention vs. removal of impacted lower third molar teeth. The number of voices highlighting the inadequacy of the current guidelines is increasing, and it is increasingly acknowledged by clinicians that in some cases, the development and progression of symptoms and pathologies can be largely predicted, and that surgery to remove M3Ms in older patients can lead to complications and patient morbidity.15, 16, 17, 18

Risks associated with retention

A study conducted at Guy’s Hospital, London, UK, investigated the clinical records of 100 patients who had 122 M3Ms removed due to distal cervical caries in the adjacent second molar.19 The study reported that the early or prophylactic extraction of a partially erupted third molar could have prevented the formation of distal cervical caries in a mandibular second molar. This suggestion was specifically related to M3Ms that were partially erupted and mesially impacted between 40° and 80° in relation to the second molar.19

In 2014, a follow-up study confirmed that distal cervical caries in mandibular second molars is a late complication of third molar retention.20 The study also confirmed that the prophylactic removal of partially erupted mesioangular M3Ms could prevent this complication.20 In 2013, Nunn et al. reported a 2.5-fold increase in the rate of distal caries in second molars adjacent to erupted third molars.21 These findings were consistent with those reported by Pepper et al. in 2017, who found a 7% increase in distal caries of a second molar when associated with a partially erupted third molar.22

In 2016, Toedtling et al. suggested the following indicators of the development of distal cervical caries in mandibular second molars: 1) the eruption status of the M3M, with longer periods of partial eruption increasing the risk of distal cervical caries; 2) the type of angulation, with mesioangular and horizontal impaction associated with 85% of the carious second molars observed; and 3) the position of the mesial cusps of the M3M in relation to the amelo-cemental junction (ACJ) of the second molar, with distal caries being notably higher when mesioangular impaction is below ACJ.17

A more recent systematic review with medium- to fair-quality evidence concluded that retained asymptomatic third molars, especially when partially erupted, were more likely to develop a disease due to impaction, age and the retention time.16 Furthermore, retention significantly increases the risk of pathology in a second molar, especially when associated with partially or mesially erupted M3Ms.16

Another study examined the impact of the NICE guidelines on the removal of M3Ms.5 The study indicated a shift in M3M removal from a young to an older adult population, with the mean age of patients undergoing treatment increasing from 25 to 32 years. However, it is important to note that age itself is not a causal factor for increased complication rates; rather, aging patients tend to have more complex health conditions that may affect their ability to cope with or recover from such procedures. The study also noted that the number of patients requiring M3M removal remained comparable to that in the mid-1990s, suggesting that the NICE guidelines did not reduce the need for treatment. However, the potential unintentional biases in the study, such as changes in the UK population between the 1990s and 2012, were acknowledged. It was unclear whether this population increase was accounted for in the study. The study also indicated discrepancies in treatment coding, data collection and the inclusion of outpatients as compared to data from the 1990s.5

Periodontal disease associated with M3Ms has also been suggested as an indication for their removal. Increased periodontal probing depths are often associated with retained M3Ms, which have been reported to serve as a reservoir harboring microorganisms linked to periodontal disease. The early removal of M3Ms may prevent the onset and progression of periodontal disease.23 However, integrating periodontal assessment into the regular monitoring and follow-up of third molars may be a more suitable approach. In a prospective cohort study involving 804 third molars with a follow-up period ranging from 3 to over 25 years, limited yet credible evidence suggested that the presence of healthy, symptom-free impacted third molars might increase the risk of periodontal disease around the adjacent teeth.3, 21 On the other hand, the surgical removal of impacted wisdom teeth has been associated with the loss of periodontal attachment on the distal part of the adjacent tooth.24

Risks associated with removal

The extraction of M3Ms is one of the most common routine procedures in oral surgery. A retrospective cohort study examined 583 patients with 1,597 third molars, finding an overall complication rate of 4.6%; the most frequent complications were alveolitis, delayed healing and damage to the inferior alveolar nerve.25

However, another prospective study assessed surgical and post-surgical complications following the extraction of M3Ms in 9,574 patients with 16,127 M3Ms removed.26 This review concluded an overall complication rate of 10.8%. Common potential complications included pain, bleeding, infection, local swelling, damage to the adjacent anatomical structures (including tooth and periodontal defects), alveolar osteitis, restricted mouth opening, incomplete root removal, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) injury, displacement, lingual nerve damage, inferior alveolar nerve damage, and jaw fracture.25, 26, 27, 28 It is acknowledged that most of these are considered the side effects of surgery rather than adverse complications.

Paresthesia

Damage to the lingual nerve and/or the inferior alveolar nerve constitutes the most serious of all the most common complications, and leads to the most frequent malpractice and negligence claims.

A retrospective study on the incidence of inferior alveolar nerve paresthesia after the surgical extraction of M3Ms included 3,286 patients.29 The study concluded that the prevalence of paresthesia as a complication of surgery was 1.5% at 1 month post procedure. However, this incidence was further reduced to only 0.6% 2 years after the procedure.29 Another study reported that in most cases, injury due to the removal of M3Ms had healed within 1–2 months after the procedure.30 A systematic review also determined that the rate of paresthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve was between 0.35% and 8.40%.31

Injury to the lingual nerve is not a common complication of the procedure. Nevertheless, it can be a significant and troubling complication when it does occur. A study that referred to 1,117 procedures found that the rate of injury to the lingual nerve was approx. 11%.32 However, full recovery from injury could take up to 9 months, with approx. 50% of patients having fully recovered within 6 weeks of the procedure. Importantly, a number of these patients (0.5%) had permanent injury to the lingual nerve and will not make full recovery.32 In another review reporting on outcomes following M3M removal, the prevalence of temporary injury was estimated between 0% and 37%, whereas the prevalence of permanent injury was estimated between 0% and 2%.33 Moreover, when injuries to the lingual and inferior alveolar nerves in patients are considered together, the incidence ranges from 0% to 15%.25, 34, 35, 36

These injuries continue to be a contentious point for both the patient and the surgeon despite their relatively low rates, especially if followed by legal disputes that become protracted and time-consuming. These injuries, especially inferior alveolar nerve and lingual nerve injuries, can lead to profoundly detrimental physical and psychological effects on the affected patients, and psychological effects on the surgeon.

Alveolar osteitis (dry socket)

Alveolar osteitis is the most common temporary complication associated with the extraction of M3Ms. Although it is not a significant concern clinically and it is relatively straightforward to manage, it can be burdensome to the patient due to the severe pain associated with the condition. It usually starts 3–4 days after surgery, radiates from the site of extraction, and is commonly associated with a foul odor and/or a bad taste. The exact cause of dry socket is still unknown, but it seems to be linked to several contributing factors, including the patient’s age, medical and dental status, smoking, patient compliance with hygiene instructions, and the complexity of the surgical procedure itself.37

Infection

Most infections associated with the removal of M3Ms can be readily managed, as, on the whole, they are self-limiting or only require local measures to resolve. However, some patients may require systemic antimicrobial therapy, or even extended hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics due to the development and progression of serious infections. A small number of patients may require further surgical intervention to treat such infections. These infections also have the potential to become systemic infections, leading to sepsis, septic shock and, rarely, life-threatening complications.38

The rate of postoperative local infections associated with the surgical extraction of M3Ms is between 0.8% and 4.2%.27 The incidence of systemic infections remains low, although the exact number is uncertain due to limited studies on the topic. A Japanese study reported a rate of deep fascial space infections after the surgical removal of M3Ms at 0.8%.39 In another study investigating 723 cases over 1 year, the rate of systemic infections involving deep fascial spaces in the neck was 0.5%.38 These patients required hospitalization, and both medical and surgical treatment.38 This highlights that while severe deep fascial space infections are rare, they are significant complications following extraction and can pose a threat to life.

Fracture

Mandibular fracture is a serious complication associated with M3M removal, but it is extremely rare, reported in approx. 0.0049% of cases.40 Although troublesome in its own right, this can also lead to litigation, especially if the outcome was not anticipated or if the fracture was associated with nerve injury.

Bleeding

Most reported intra- and postoperative bleeding can be adequately controlled with local measures. However, there are cases of excessive bleeding associated with M3M extraction, reported to range between 0.2% and 58.0%.27 Excessive bleeding can lead to the formation of hematomata, the stiffness of the mastication muscles, trismus and, in severe cases, airway obstruction and significant patient morbidity. The most worrisome cases of excessive bleeding are those potentially associated with patients who have bleeding disorders that have not been previously diagnosed, such as hemophilia A or B, von Willebrand disease, and mandibular artero-venous malformations.26 Unfortunately, some disorders may not be suspected until problems arise during or after surgery, as the removal of M3Ms may be the first surgical intervention many patients encounter.28, 41, 42, 43

Displacement

The displacement of third molars, third molar roots or third molar fragments is another rare complication that can lead to serious issues. In a review by Di Nardo et al., it was noted that the most frequently reported site for mandibular displacement is the submandibular tissue space.44 Other reported sites include the sublingual space, the pterygomandibular fossa, the buccal space, the lateral cervical space, the lateral pharyngeal space, and the body/ramus of the mandible.25, 27, 28, 45 Depending on the location of displacement and proximity to vital structures, attempts at retrieval could complicate matters and necessitate unintended surgical procedures.

Other complications

There are several other potential complications associated with the removal of M3Ms. However, a detailed discussion of self-limiting complications that are easily managed is beyond the scope of this paper.

Introduction to the proposal

The available guidelines on the extraction of third molars are limited in number, and are mostly tailored to specific settings or countries. However, there are no widely used guidelines available to assist the international community in the decision-making process. The purpose of this proposal is to provide further details about the existing guidelines and recommendations. This proposal is primarily based on the published guidance, with amendments to include the most appropriate and salient points from each. This proposal could potentially be used and further developed by the international community to establish consensus, and assist both patients and clinicians alike. More specifically, this protocol should be considered as a guide only to help in the decision-making process.

Since the future of such unpredictable teeth cannot be accurately anticipated, clinical judgment should always be exercised. Cases should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, with the final decision based on a joint agreement between the patient and the clinician.9

All patients should be fully informed about the advantages, disadvantages, risks, benefits, and the potential complications associated with the removal or retention of M3Ms.

Patients should be actively involved in the decision-making process.

Purpose of the proposal

The purpose of the current proposal is:

– to prevent the inappropriate prophylactic removal of M3Ms;

– to prevent the inappropriate retention of M3Ms;

– to provide help and guidance in the decision-making process regarding M3M removal; and

– to reduce the risk of exposing the patient to unnecessary harm and complications due to the inappropriate removal or retention of M3Ms.

Proposal

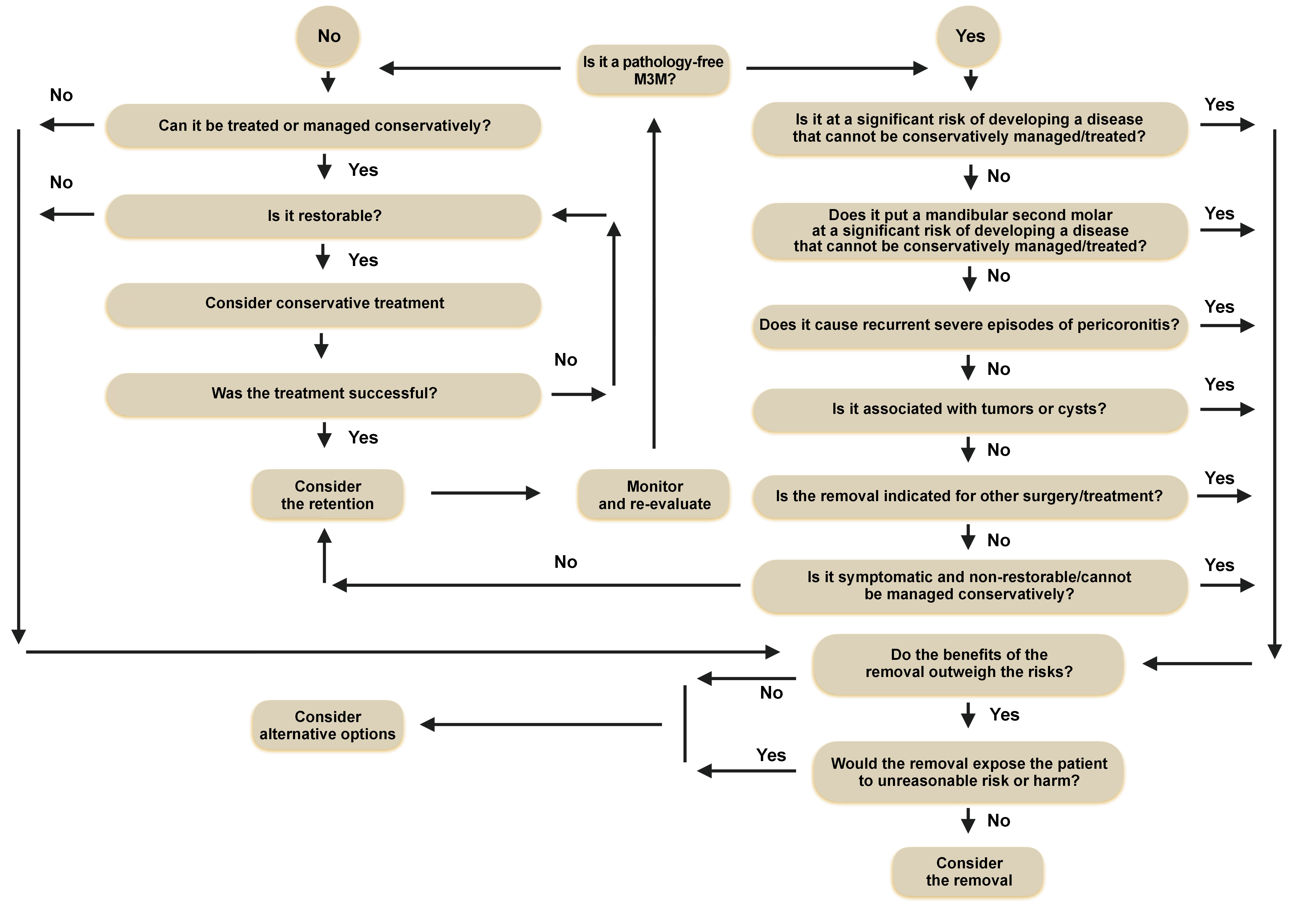

Pathology-free impacted M3Ms should not be removed6 unless they are at a significant risk of developing a disease7, 9 that cannot be conservatively managed or treated.

The prophylactic extraction of healthy M3Ms should be discontinued6 unless mandibular second molars are at a significant risk of developing a disease7 that cannot be conservatively managed or treated.

The first episode of pericoronitis should be treated conservatively and should not be considered as an indication for surgery. Depending on their severity, recurrent episodes of pericoronitis may be considered an indication for surgery.6

The absence of symptoms does not indicate the absence of a disease. Therefore, regular follow-up, clinical assessment and/or radiographic surveillance are advisable.9

Pathologies or conditions that may justify surgical intervention

The following pathologies or conditions may justify surgical intervention:

– non-restorable wisdom teeth and/or untreatable tooth decay, and pulpal and/or periapical pathology6;

– abscesses, cellulitis and/or osteomyelitis6;

– tumors or cysts6;

– pathologies of the tooth and/or the adjacent structures that cannot be treated conservatively6;

– the tooth obstructs other surgery/treatment or its removal is indicated for other surgery/treatment6, 9;

– the associated tissue requires histological examination9; and

– the overlying removable prostheses.9

The management flowchart for M3Ms is presented in Figure 1.

Other considerations

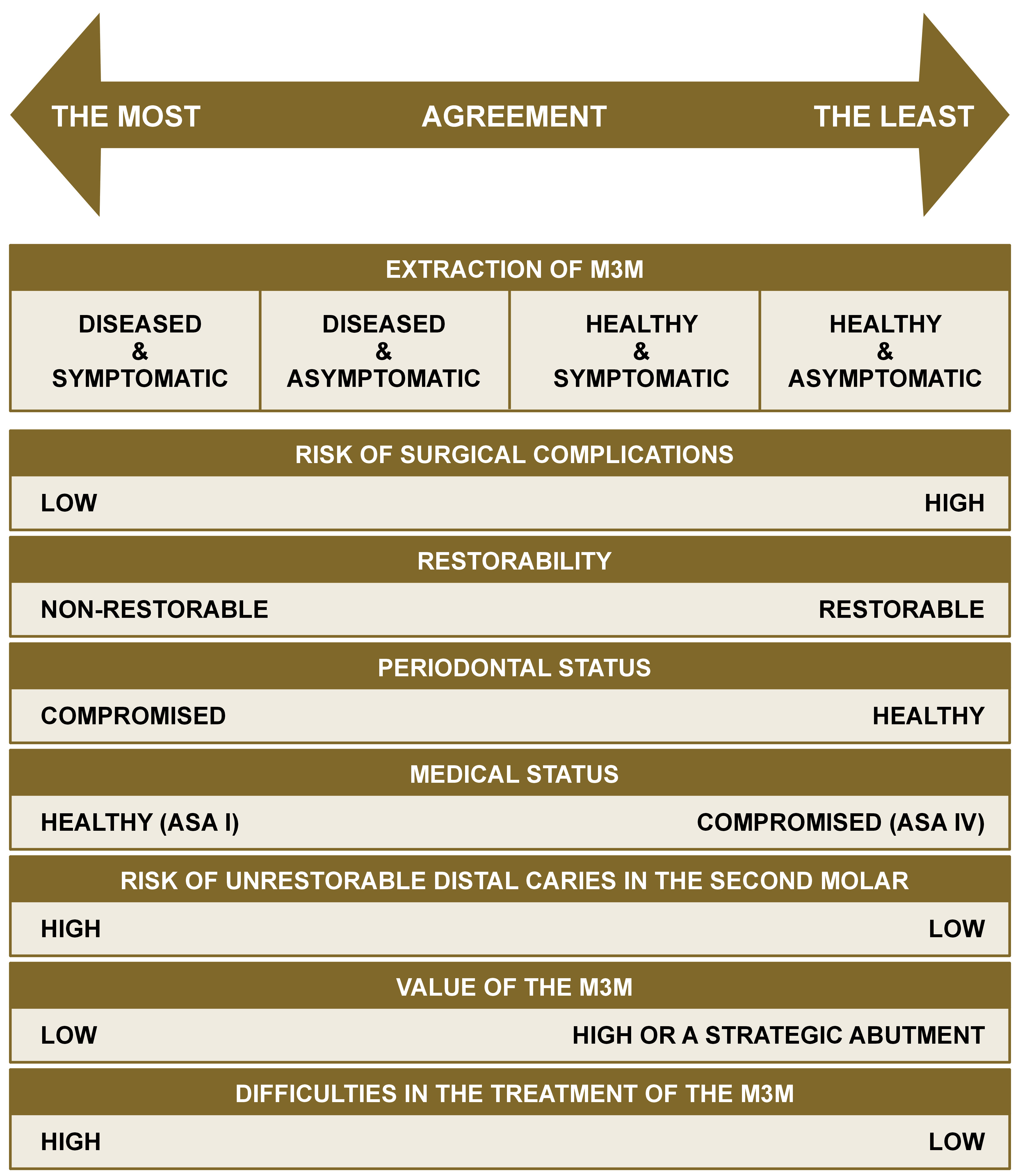

Generally speaking, there is agreement that diseased, symptomatic and non-restorable M3Ms should be removed. However, for healthy, asymptomatic and restorable M3Ms, there is less consensus (Figure 2).9

The most frequent dilemmas faced by clinicians regarding M3Ms include the following:

– the risks and benefits associated with the surgical removal of M3Ms9;

– the risks and benefits associated with the retention of M3Ms9;

– the risks and benefits associated with the partial removal (coronectomy) of M3Ms9;

– the risks and benefits associated with the surgical exposure of M3Ms9;

– the most appropriate timing for treatment9;

– the patient’s age and the likelihood of developing associated diseases6, 7, 9;

– the current symptoms6, 9;

– the position, angulation, eruption, and anatomy of the M3M7;

– the functional, periodontal and carious status of the M3M6, 7, 9;

– the feasibility of other treatment and the restorability of the tooth6, 7, 9;

– the cost associated with the surgical removal of M3Ms9;

– the cost associated with the retention of M3Ms9; and

– the most appropriate plan for follow-up, clinical and radiographic examinations.9

Contraindications for the removal of M3Ms

Below are presented the contraindications for the removal of M3Ms:

– the removal would expose the patient to unreasonable risk or harm7;

– unerupted, healthy and asymptomatic M3Ms that are fully covered by bone, with no potential risk of developing a disease7; and

– healthy and asymptomatic M3Ms that are at a minimal risk of developing a disease and can be treated conservatively.9

Conclusions

It is obvious that the indications for the extraction of M3Ms will continue to be an area of controversy and strong debate. The evidence for or against prophylactic extraction is ambivalent; there is evidence to accept or reject the stance against prophylactic extraction in some specific cases, and there are published articles to support both opposing views.

In the UK, NICE stated that “there is no reliable research evidence to support a health benefit to patients from the prophylactic removal of pathology-free impacted third molar teeth”.6 The AAOMS white paper stated that “uncertainty is more explicit in the case of patients who have asymptomatic, disease-free third molars”,9 while the Finnish guidelines stated that “patients would benefit markedly from elective preventive removal of third molars”.7

In 2016, a study undertaken by Cochrane reviewed the prophylactic removal of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth against their retention, and concluded that “insufficient evidence is available to determine whether or not asymptomatic, disease-free impacted wisdom teeth should be removed”.3

The unpredictable nature of M3Ms will continue to cause controversy, especially in providing universally accepted guidelines for their removal. It is acknowledged that in the vast majority of cases, their removal goes without incident, but in a small but significant number of patients, the sequelae of removal can have a profound negative impact on the patients and their quality of life. However, in recent years, there has been growing evidence that the retention of asymptomatic and disease-free M3Ms can also lead to adverse outcomes, including the loss of the adjacent second molars, many of which could have been prevented if removal had been undertaken earlier.

Therefore, while it may be wise to take extra caution when considering the prophylactic removal of such an unpredictable tooth, anticipating which teeth may cause problems in the future may help influence our decision-making process for the long-term benefit of both the patient and the clinician.