Abstract

Background. Dentists, through inappropriate antibiotic prescription, may contribute to the global problem of antibiotic resistance (AR).

Objectives. Understanding dentists’ antibiotic prescription patterns, source of knowledge, and the driving forces behind their prescription practices may be crucial for the effective implementation of the rational use of antibiotics (RUA) in dentistry.

Material and methods. Active members of the Turkish Dental Association were invited to participate in an electronic survey comprising questions focusing on their role, knowledge and perceptions regarding RUA, the perceived barriers to adapting RUA in daily dental work, and the actual antibiotic prescription practices. The potential impact of age, gender, professional experience, and the mode of dental practice was also evaluated. Dentists’ prescription practices for periodontal disease/conditions were evaluated as well.

Results. Based on 1,005 valid responses, there was consensus on the necessity of RUA (99.1%); however, its implementation was low. The main barriers were dentists’ own safety concerns (74.4%), strong patients’ demands (42.2%) and the fact that prescribing antibiotics became a professional habit (35.8%). Different educational background resulted in clear variances in everyday prescription practices.

Conclusions. The implementation of RUA was not sufficient and the perceived barriers had an impact on daily prescribing habits. Support for dental professionals through the efficient dissemination of evidence-based clinical guidelines and decision-making aids is likely to require additional help from professional organizations in order to actively combat AR.

Keywords: antibiotics, antibiotic resistance, public health dentistry, dental practice pattern, evidence-based dentistry

Introduction

While interventional treatment is becoming more and more successful in controlling dental infections, antibiotics are increasingly being limited to specific therapeutic/prophylactic indications.1, 2 Most healthcare professionals are perfectly aware that the unnecessary use of antibiotics is a global problem; nonetheless, the inappropriate prescription rate is high in both developed and developing countries.3 Most oral healthcare professionals prescribe antibiotics empirically, either for prophylaxis or for managing infections. However, there is disagreement over whether systemic antibiotics provide therapeutic benefits in all cases.4 Additionally, the irrational or inappropriate use of antibiotics is still common for caries, gingivitis, pulpitis, and apical inflammation therapy, conditions that could be managed by dental procedures.5

Since antibiotic resistance (AR) is a complex, multisectoral and multifactorial problem, it is crucial that the various factors underlying AR be fully evaluated if we are to combat this issue effectively. These factors include: the lack of standardization in prescription; barriers in transferring evidence-based dentistry (EBD) principles to daily practice; and limited dissemination and effective implementation of clinical guidelines (CGs).6, 7 Health professionals’ perceptions and attitudes toward AR are also a matter of concern.7 Considering that dentists are responsible for about 10% of the antibiotics prescribed, dental professionals need to minimize their contribution to AR.8, 9

In addition to physicians’ prescribing behavior, socio-demographic factors (medical education, previous experience, etc.), physicians’ attitudes (ignorance, fear, etc.), patient-related factors (allergies, economic and social factors, etc.), healthcare-related factors (time pressure, patient load, etc.), and miscellaneous other factors (e.g., cost-saving), have been suggested to play significant roles with regard to this problem.2, 10 As reported for general medical practice, dentists’ decision making concerning antibiotic prescription, selection and timing, as well as treatment duration often varies depending on their experience, knowledge and social factors.5 Together, these data highlights the role of non-medical factors in the antibiotic prescription practices of healthcare professionals.

When the role of organized dentistry and individual dental professionals in combating AR is considered, the daily prescription practices of dental professionals, the perceived barriers to the effective implementation of the rational use of antibiotics (RUA), the responsibility of organized dentistry, and dental professionals’ perceptions and attitudes toward AR and RUA may be of significant importance.4, 8 The analysis of variances in dentists’ prescription patterns, and the potential impact of gender, age, years of professional experience, and the mode of practice may also deserve further professional interest. In the present study, our aim was to evaluate AR issues from a dental perspective.

Material and methods

Development of the questionnaire

and its validity

A questionnaire was designed to analyze dentists’ familiarity with RUA, their perceptions and attitudes toward RUA, the perceived barriers to the effective implementation of RUA, and dentists’ antibiotic prescribing habits during their actual practice. The questions were adapted from previous studies and modified in line with the aim of this study.11 A preparatory survey was carried out to increase the validity and practical applicability of the questionnaire, and to provide further clarification. In the preparatory study, the questionnaire was administered to a group of 30 dentists of different background. The questionnaire was subsequently modified in line with the received feedback.

Structure and content of the questionnaire

The questionnaire basically comprised 2 sections (plus 5 initial questions on demographic data and professional characteristics). The 1st section concerned AR and the principles of RUA, while the 2nd section focused on the implementation of RUA with regard to daily dental practice (taking a prescription for systemic antibiotics for the treatment of periodontal diseases/conditions by dentists as an example). In the 1st section, there were 12 questions concerning dentists’ knowledge and perceptions about AR and RUA (one of which was multiple-response), and 2 questions about the medical and non-medical factors affecting dentists’ antibiotic prescription (both multiple-response). In the 2nd section, there were a total of 7 questions concerning the benefits, timing, and choice of systemic antibiotics, as well as indications for their use in the treatment of periodontal diseases/conditions. Potential mistakes when prescribing antibiotics for the treatment of periodontal diseases/conditions were also considered (Table 1).

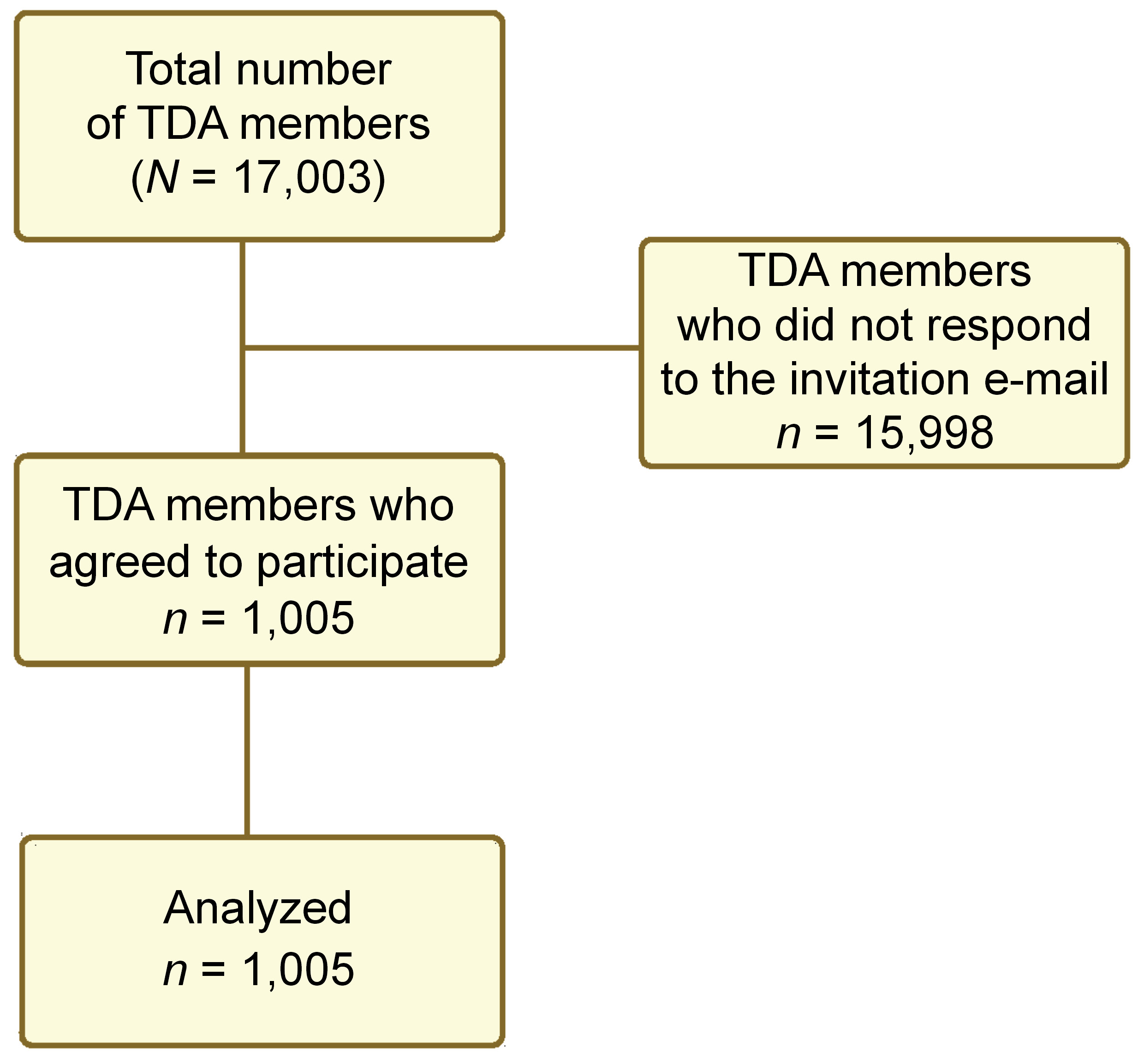

Sample size calculation and conducting the survey

The sample size calculation was based on the total number of the Turkish Dental Association (TDA) members in 2017, which was 17,003. Thus, the required representative sample to reject a null hypothesis at a 0.05 margin of error and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was 376 (the minimum sample size). The TDA conducted the survey electronically among its members between June 9, 2017 and October 1, 2017. All members were asked to participate by sending a link to the survey (recorded as a Google Survey) to their registered e-mail addresses in the source mailing list for TDA.

Statistical analysis

Out of the total number of 17,003, 1,005 (5.9%) dentists accepted our invitation to participate (Figure 1). The survey data was entered into a statistical software package (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v. 24.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).12 The answer ratios were determined, and statistical analyses were performed. All associations for the variables of gender, age, years in dental practice, and the professional status were analyzed using the χ2 test. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic data and professional characteristics

All data of 1,005 dentists participating in the study was included in the statistical analysis phase. In total, 55.6% of the participants were male and 43.4% of the participants were female, and most (80.3%) were general dental practitioners (GDPs). The dentists’ distribution with regard to the total number of years spent in dental practice was as follows: between 1–5 years (25.3%); and more than 25 years (26.3%). In most instances, the dentists’ practice mode was a private clinic (47.1%), with a polyclinic/shared practice coming second (27.2%) (Table 2).

Dentists’ knowledge and perceptions about RUA

Almost all of the dentists surveyed agreed on RUA (99.1%), and agreed that antibiotics should be prescribed only in case of need (98.9%). However, 69.0% thought that antibiotics were not prescribed only in case of need. According to 71.5%, dentists’ knowledge about RUA was insufficient. Only 37.0% of the participants thought that the available scientific information and resources were sufficient to support dentists’ decision making about RUA. Almost all respondents (98.1%) thought that universities and organizations should put more emphasis on RUA (Table 3).

While almost all participants (97.6%) agreed that dentists should inform their patients how to use antibiotics rationally, only 38.9% thought that their colleagues were actually informing patients. According to 68.3% of the dentists, their colleagues did not know enough about the indications, contraindications, mechanisms, side effects, and interactions regarding antibiotics. In general, our data highlighted a significant gap between dentists’ beliefs and attitudes and the actual practice regarding AR and RUA (Table 3). Undergraduate education (73.7%) was the primary source of knowledge about RUA, followed by continuing courses (57.2%) and publications (53.2%). Only 23.9% of the participants considered guidelines as the source of dentists’ information about RUA (Table 4).

Factors affecting dentists’ antibiotic prescription and the potential barriers to adopting RUA

The predominant medical factor considered during prescription was the patient’s medical status and/or pregnancy or lactation (76.9%), followed by the patient’s history of allergy (75.8%). The dentists listed clinicians’ past experience (74.8%), the patient’s age (73.7%), disease severity (68.8%), and diagnosis (68.2%) as other main prescription considerations. Evidence regarding antibiotic use was considered only by 17.7% of dentists, while the risk of AR was considered by 38.9% (Table 4). ‘Feeling safe’ was the non-medical criterion expressed the most (74.4%). The patient’s demands (42.2%) and expectations (40.3%) were other non-medical factors considered (Table 4).

Impact of age, gender, professional experience, and the mode of practice

Disagreement with the opinion that dentists complied with RUA increased as years in practice decreased (p = 0.002). Additionally, dentists with fewer professional practice years agreed more with the opinion that dentists did not provide adequate information for their patients (p = 0.008). While more female respondents were of the opinion that dentists should inform their patients about RUA (p = 0.003), more male dentists expressed the opinion that their colleagues prescribed antibiotics only when necessary (p = 0.029) (Table 3).

In comparison with specialists, GPDs more believed in the need to inform patients (p = 0.001), whereas specialists less believed in the rationality of dentists when prescribing antibiotics and the adequacy of their knowledge about RUA as compared to GPDs (p < 0.001). Furthermore, more specialists expressed the opinion that although current scientific resources should be followed by dentists, they were not being followed in practice (p = 0.001). In contrast to GPDs, most specialists expressed the opinion that the available scientific sources were sufficient (p < 0.001). However, more dentists working at universities were of the opinion that the available scientific resources were sufficient as compared to dentists working in private clinics, polyclinics or hospitals (p = 0.002) (Table 3).

Prescription of systemic antibiotics for the treatment of periodontal diseases/conditions

Periodontal diseases/conditions associated with systemic signs and symptoms (83.9%), periodontal abscess (58.3%) and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (52.4%) were the most frequent indications for antibiotic prescription. In otherwise healthy individuals, the most frequent cases in which antibiotics were prescribed were cases of regenerative treatment (69.3%) and periodontal surgery (63.5%) (Table 5). Although almost all of the participating dentists believed that systemic antibiotics without mechanical debridement were not beneficial, there were significant differences in the ideal timing for the prescription of antibiotics as an adjunct to mechanical debridement (before: 21.3%; during: 33.9%; after: 35.8%). In addition, age (p < 0.001), years in dental practice (p < 0.001), the professional status (p = 0.008), and the mode of practice (p < 0.001) all had a significant impact on the preferred timing for antibiotic treatment. Most of the participants (62.5%) felt that dentists did not keep up-to date-with the current regimens for antibiotic prescription in the treatment of periodontal diseases/conditions. Again, age (p < 0.001), years in dental practice (p < 0.001), the professional status (p < 0.001), and the mode of practice (p < 0.001) all had an impact on the responses (Table 6).

Prophylaxis seemed to be a major indication for systemically compromised cases undergoing dental treatment (e.g., mitral valve prolapse, immune system dysfunction, etc.). The incorrect indication (64.6%), the incorrect choice of antibiotics (62.1%) and the early cessation of antibiotic treatment (61.0%) were listed as the major mistakes made when prescribing systemic antibiotics in the treatment of periodontal diseases/conditions (Table 7).

Discussion

Since the evaluation of the actual antibiotic prescription practices of dentists in their daily dental work was the main aim of the present study, the 2nd section of the questionnaire was devoted to periodontal practice and dentists’ prescription patterns for the treatment of periodontal diseases/conditions. Although academic knowledge may not always be translated to dental practice, the up-to-date knowledge of RUA and appropriate antibiotic prescription practices among health professionals are still required.5, 13 The suboptimal knowledge of dental professionals in the field of RUA and clear variations in antibiotic prescribing practices among dentists have been frequently mentioned in earlier studies.1, 5, 14, 15, 16, 17 In the present study, most of the dentist respondents highlighted the suboptimal knowledge of dentists regarding the principles of RUA (71.5%) and their inability to keep up-to-date in this field (71.9%). Although all dentists acknowledged AR as a serious health problem, they doubted if RUA was effectively implemented into daily dental work. Interestingly, suboptimal knowledge was addressed more as years in practice decreased (p = 0.002). In line with previous studies,13, 14 the failure of dentists to keep up-to-date with best practices for prescribing systemic antibiotics in the treatment of periodontal diseases/conditions (62.5%) was again confirmed. Furthermore, there were clear differences in the appropriate timing of antibiotics reported and in appropriate periodontal antibiotic indications. Again, these results support previous studies suggesting the lack of standardized prescription procedure for dentists in daily practice.14, 15, 18

For the majority of the participating dentists, the need for effective knowledge transfer to enable dentists to make decisions using the most recent, reliable and evidence-based resources was acknowledged, which again was in line with previous studies.7, 14 In this respect, well-conducted stewardship courses and training programs (e.g., continuing education courses, dental congresses, etc.) addressing the needs of the whole dental team have been broadly suggested.17, 19 In the present study, only 37.0% of the participants believed that the scientific information and resources concerning RUA readily available were sufficient to support dentists, while almost all (98.1%) thought that universities and organizations had to put more emphasis on RUA.

Pre-appraised evidence (e.g., systematic reviews, CGs, etc.) may help dentists in making evidence-based decisions,16, 17 and CGs such as “Drug prescribing for dentistry”,20 the evidence-based clinical practice guideline on the nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis21 and “Prevention and management of dental caries in children”22 may be important for the effective implementation of RUA. These documents recommend antibiotics only for cases when they are strictly indicated (e.g., systemic involvement or in conjunction with mechanical dental/periodontal treatment).23 However, in numerous countries, CGs do not seem to be systematically disseminated or effectively implemented.24 A cross-sectional study reported that only 19% of antibiotic prescription by UK dentists was compliant with CGs;18 many practitioners were either not aware of CGs or considered them as a reducer of their professional autonomy, and only about 50% of the practitioners found CGs helpful in daily clinical decision-making.7 In the present study, while undergraduate education (73.7%) and continuing educational courses (57.2%) were reported as the major sources of information, only 23.9% of the dentists benefited from CGs about RUA. Since almost all participants in the present study supported the need for more emphasis to be placed on RUA by dental organizations, additional efforts from these organizations are required to develop and disseminate CGs that would increase knowledge regarding AR and RUA. Moreover, dental organizations should also provide support for the whole dental team through other decision-making support materials (e.g., publications, courses, audits, patient education materials, awareness campaigns, etc.).

As the main reasons for the growth of AR comprise patients not completing their course of treatment, self-prescription (including the use of leftover antibiotics), and poor hygiene and sanitation habits, the education of dental patients may be paramount in combating AR.25 A qualitative study conducted amongst adolescents revealed that antibiotics were perceived by patients on the same level as analgesics, as a cure-all for any illness.26 Thus, health professionals are expected to inform their patients about their role, responsibility about AR and its significant consequences.4 In the present study, despite the almost universal (97.6%) belief that dentists should provide information to their patients concerning AR and RUA, our respondents felt that this was ignored in daily dental practice (56.0%). All health professionals need to reconsider their role and responsibility in combating the global problem of AR. This can be achieved by effectively communicating to their patients updated information about RUA, AR and the negative outcomes of antibiotic misuse, and by helping them reach the necessary educational resources.27 Additionally, this may also help dentists manage the demands of dental patients for antibiotics, which is an important driving force for inappropriate and unnecessary antibiotic prescription by the dentists.24 This problem was also mentioned in the present study.

The observed heterogeneity in dentists’ antibiotic prescription practices and the driving forces behind this heterogeneity, together with the potential barriers to effective implementation of RUA, are of particular importance for developing strategies to achieve compliance with RUA.6, 7, 16 Other studies have confirmed this fact, with up to 80% of antibiotic prescriptions by UK dentists found to be either unnecessary or inappropriate.9 Similarly, Fleming-Dutra et al. reported that a 30% reduction in prescriptions was achievable.28 In the present study, 69.0% of the dentist respondents believed that unnecessary antibiotics were prescribed by dentists. The 2 major non-medical driving forces for prescriptions were listed as the practitioners’ own safety (74.4%), and patient-related factors, including the patient’s demands (42.2%) and expectations (40.3%). Together, these findings emphasize the importance of enhancing the quality of prescribing in dentistry.29

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are generally prescribed by dentists empirically for prophylaxis or to manage oral/dental infections.15, 25 Amoxicillin (alone or in combination with clavulanic acid), metronidazole, clindamycin, and azithromycin are commonly used systemic antibiotics in dental practice.30, 31, 32 However, there are conflicting reports on whether systemic antibiotics provide a therapeutic benefit in all cases. Alternative approaches, including the use of drug delivery systems that keep the local antimicrobial concentration in the application area at a high level, reduce the need for systemic antibiotic use in dentistry, and they have a decreased associated risk of promoting AR.33 Numerous local drug delivery systems have been successfully trialed, including fibers, gels, membranes, microparticles, nanoparticles, and liposomes, as well as novel carrier forms developed for this purpose.2, 34 Constant levels of antibiotics, including tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline, metronidazole, etc., can be maintained using these systems.2, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 It should also be stated that the recommended interventions (e.g., root canal therapy, scaling and root planing) are effective, and that the antibiotic need is very limited in practice.24, 29, 40

Although the medical status, a history of allergy and disease severity were among the most frequently considered factors in the present study, a unanimous set of criteria for antibiotic prescription in terms of medical/dental reasoning was not observed. It can be concluded that what should be in the focus is the individual risk assessment in decision making for prescription.41 Dentists are expected to make judicious use of antimicrobials and prescribe the correct drug at the standard dosage in the appropriate regimen, and only when a real need is evident.24, 29, 42 However, it is known that health professionals’ decisions are affected by a wide array of factors, including educational and training background, and differences in local circumstances. Their attitudes and perceptions are also important. At this point, the perceived barriers to effective implementation of RUA expressed by dentists are naturally of utmost importance. Dentists report the lack of time, education and accessible CGs as the major barriers to adapting EBD to daily practice.7 In future endeavors, the multifactorial and multisectoral nature of AR should be considered, and the need for partnerships, collaborations and innovative approaches involving different stakeholders should be taken into account as well. Together, these considerations can initiate cooperation between different parties, including organized dentistry.16 Although there are encouraging steps,8 AR remains a global problem despite all our efforts. This needs to be acknowledged by the dental profession (dental organizations, individual dentists, and other dental team members), and effective measures should be taken to combat AR.

Limitations

An inherent limitation of our study is that it was based on a survey that included questions evaluating individual perceptions. However, the high number of dentist participants increases the strength of our study. Another limitation is that the study was based on a single-country survey, whilst antibiotic usage habits may differ in each country. Nevertheless, the information obtained here should help to generally address barriers to RUA in dentistry.

Conclusions

Dental health professionals have several important roles to play in combating AR, including preventing the unnecessary prescription and/or misuse of antibiotics, informing patients about AR and RUA, keeping up-to-date with advances in this field, and making evidence-based decisions using the most current and reliable data. Considering problems with prescription practices, professional attitudes toward RUA, the level and extent of dentists’ knowledge, and the perceived barriers, practitioners may need professional guidance to effectively implement RUA into daily work. Furthermore, based on the impact of gender, age, and the mode and years of practice on the antibiotic prescription patterns of dentists, trends in AR and RUA, and the prescription patterns of dentists may need additional monitoring.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at the Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2008 (No. GO 17/490-10).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.