Abstract

Background. Several risk factors contribute to the development of dental caries in children, including sociodemographic, dietary, oral hygiene-related and other miscellaneous factors. Maternal smoking was highly associated with dental caries when compared to smoking by fathers or other household members.

Objectives. The aim of the study was to determine the prevalence of dental caries and their association with exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) among 5- to 10-year-old students attending private and government schools.

Material and methods. A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted among schoolchildren. Data was collected from the primary caregivers using a pre-tested form to assess the ETS exposure under 5 domains based on history: antenatal exposure; exposure during the index period; exposure in the school neighborhood; exposure in restaurants/roadside stalls; and exposure in bus stops/railway stations. Dental caries was assessed based on the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines from 1997. The association was reported using prevalence ratios (PRs) (95% confidence interval (CI)).

Results. Data was obtained from 211 schoolchildren attending government (39.8%) and private schools (60.2%). The overall prevalence (95% CI) of dental caries was 49.3% (42.5–56.1%). Among all the risk factors evaluated in the study, exposure to ETS was associated with a significantly increased risk of dental caries. The adjusted prevalence ratio (APR) of ETS exposure varied with the mother’s educational status and high sugar exposure, although this was statistically insignificant.

Conclusions. The prevalence of dental caries among schoolchildren aged 5 to 10 years in the city was moderate and similar to the national average. Among the risk factors assessed in the study, antenatal exposure to ETS was found to significantly increase the prevalence of dental caries by 41% after adjusting for other factors. Therefore, it is important to educate parents on the causal role of ETS exposure in dental caries.

Keywords: prevalence, risk factors, dental caries, environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure

Introduction

Dental caries is a microbial disease defined as “a biofilm-mediated, diet modulated, multifactorial, non-communicable, dynamic disease resulting in net mineral loss of dental hard tissues.”1 The prevalence of dental caries has increased globally among the age group of 5 to 10 years over the past few decades.2 Dietary habits and other exposures outside the home are often initiated during this time, as schooling typically begins at this age. From 2000 to 2015, the global median prevalence (range) of dental caries among lower-middle-income countries in 5- to 6-year-old children was 83.4% (64.0–88.6%).3 In India, the pooled prevalence of dental caries in children aged 5 to 10 years was 49%.4

The development of dental caries can be attributed to various risk factors, including sociodemographic, dietary, oral hygiene-related and other miscellaneous factors.5 Among dietary factors, sugar exposure has been consistently associated with dental caries.6 Although extensively studied, ambiguity remains regarding some hypothesized risk factors, such as exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS). The ETS, or secondhand smoke, is defined as the smoke exhaled by a tobacco smoker and the smoke released from the lighted end of a cigarette. There is evidence supporting the causal relationship between smoking and dental caries in adults. Additionally, ETS exposure is linked to a reduction in vitamin C levels. It was demonstrated that low vitamin C levels could increase the proliferation of Streptococcus mutants.7 An in vitro study was conducted to observe the growth of S. mutants and Streptococcus sanguinis in 3 different media atmospheres, namely air, carbon dioxide and cigarette smoke.8 Research has shown that nicotine can facilitate the proliferation of these cariogenic bacteria.9 In addition, exposure to ETS has been shown to impair immunity through various mechanisms, including the reduction of serum immunoglobulins (IgG), suppression of T-helper cells and limitation of phagocytosis.10, 11

Children are more susceptible to the adverse effects of ETS exposure due to their rapid breathing rate and high surface-to-volume ratio. They tend to inhale more toxic chemicals per unit of time than adults. A systematic review of studies on permanent dentition reported that 10 out of 11 studies showed a significant association of ETS exposure with dental caries.12 The impact of smoking on dental caries was often overshadowed by the effect of sugar intake in children.

Systematic reviews on the effect of ETS on dental caries in children have demonstrated the causative role of antenatal exposure; however, postnatal exposure is still debated.13, 14 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported a positive association between postnatal exposure to smoking and dental caries.15 Maternal smoking was associated with a higher prevalence of dental caries in children compared to paternal or other household members’ smoking.15 Most studies on the effect of passive smoking and dental caries in children have been conducted in upper-middle and high-income countries where smoking among women is prevalent. In India, however, the prevalence of smoking among women is low. As per the Global Adult Tobacco Survey-2 (GATS-2), the estimated prevalence of tobacco smoking is 2%.16 Since exposure to ETS in India is low, its effect could remain hidden. Evidence suggests an association between passive smoking and dental caries in Indian children. Hence, the present study was designed to assess the prevalence of dental caries and their association with ETS exposure.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional analytical study was conducted from July 2019 to January 2021 in children aged 5 to 10 years who were enrolled in selected government and private schools. Most schools conduct regular health check-ups, including oral health screening, for their students. Children with any systemic illness or psychiatric disorders were excluded from the study. The estimated sample size was 207. The sample size was calculated using OpenEpi v. 3.1 (https://www.openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm) with a type I error of 5%, assuming a caries prevalence of 65% and a relative precision of 10%. Stratified cluster sampling was conducted to select schools for the study. Each school was considered a cluster of the survey. We divided primary schools in the city into government and private schools, and the sample size was proportionally distributed between them. Schools were selected from each stratum to ensure the representation of different municipal wards in the district. The primary investigator obtained permission from each school principal to recruit children for the study. Parents were informed about the study by teachers via the school diary. Four government schools and 4 private schools agreed to participate in the study. All eligible children from the selected schools were enrolled in the study after obtaining informed consent from the mother or primary caregiver. A total of 211 children were included in the study, 127 from private schools and 84 from government schools. The age of the children was 7.8 ±1.8 years.

A pre-tested semi-structured form was used to collect information from the mothers or primary caregivers of the children. The study form included data on possible risk factors such as sociodemographic factors, diet-related risks, oral hygiene, and ETS exposure. The form was piloted with the mothers of children visiting the outpatient department and was modified based on their feedback for final use. The education level of the parents was determined using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED),17 their occupation was recorded using the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08),18 and their composite socioeconomic status was classified using a modified Kuppuswamy socioeconomic status scale 2019.19

The child’s oral hygiene was assessed based on the following parameters: the mode of teeth cleaning; the frequency of teeth cleaning; brushing by parents or under parental supervision; brushing before bedtime; and the type of toothpaste used or its alternatives. In addition, the information on the brand of toothpaste was noted to confirm the use of fluoride-based toothpaste. The duration of breastfeeding, breastfeeding during sleep time and bottle feeding (duration, age and frequency) were also recorded. The child’s current sugar intake was obtained from the mother using a 24-hr dietary recall method. Information was collected on the type and amount of meals consumed. Sugar exposure was scored based on the consistency, style and frequency.20 The primary caregiver was interviewed to obtain information on ETS exposure. The child’s exposure to ETS was assessed in 3 domains: exposure during the antenatal period, i.e., 1 year from the date of interview, and exposure outside the household. Exposure to ETS was considered present if any household member had a smoking history during the antenatal or index period. The index period for this study was 1 year, based on expert consultation. The study assessed exposure to ETS outside the household at 3 key locations: the school neighborhood; restaurants/roadside stalls; and bus stops/railway stations. Exposure to ETS was considered present if the primary caregiver observed smoking at any of these premises.

Clinical examination followed the World Health Organization (WHO) type III diagnostic criteria for oral health surveys.21 During the data collection period, none of the children reported symptoms suggestive of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to strict isolation measures implemented by the school authorities. The children were examined in daylight and their dental caries status was determined using the Decayed, Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index. The DMFT index was used to document the dental caries status in permanent dentition, while the decayed, extracted, filled teeth (deft) index was used in mixed dentition. To avoid inter-examiner variability, a single calibrated investigator conducted all examinations, and an assistant recorded the values. Based on the diagnosis, appropriate treatment was provided, or a referral was made based on the condition.

Statistical analysis

The study reported the prevalence of dental caries with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The association between ETS exposure, other risk factors and dental caries was examined using the χ2 test. The effect estimate was summarized as the prevalence ratio (PR) (95% CI). Prevalence ratios were assessed using the binomial regression function in Stata 14 (StatCorp LLC, College Station, USA). The mean/median difference in the DMFT index and deft score between the exposed and unexposed was assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Multivariate analysis was conducted using log-binomial regression to determine the adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI). In the univariate analysis, all variables with a p-value <0.5 were included in the multivariate analysis, and variables showing multicollinearity were excluded. The analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software, v. 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

Results

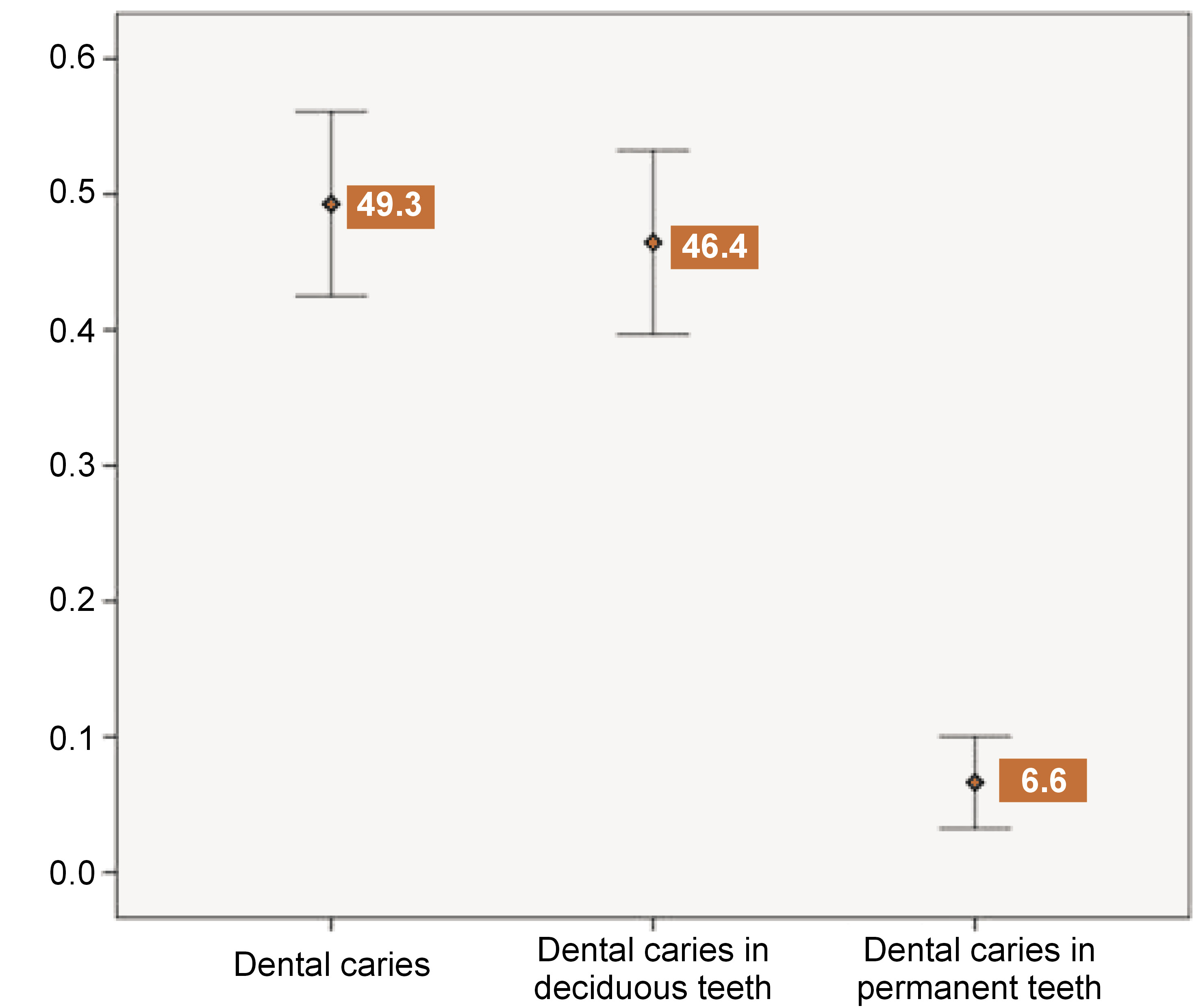

Data was collected from 211 children. Of these, 60.2% (n = 127) attended private schools, and the majority were boys (56.9%; n = 120). The mean age (± standard deviation (SD)) of children in government schools was 7.7 (±1.7), which was comparable to that of private schools (7.9 (±1.8)). The sociodemographic distribution of the study sample is presented in Table 1. At least one-third of the mothers (33.6%) and two-fifths of the fathers (42.2%) of the children completed graduation, i.e., reached ISCED levels 6 and 7. One-fourth of the households were engaged in elementary occupations, such as daily-wage work, while 30% were involved in higher-level occupations, including technicians, associate professionals and professionals. A similar distribution was observed in the socioeconomic class, with a slight majority (54.6%) belonging to the lower strata, i.e., upper lower and lower middle levels. The median per capita income (interquartile range (IQR)) of households in the study sample was 3,750 (2,500–6,667) Indian rupees (INRs). The prevalence of dental caries is represented as an error bar in Figure 1. The overall prevalence of dental caries was 49.3% (42.5–56.1%). A significantly higher prevalence of dental caries was observed in primary teeth (46.4% (39.8–53.3%)) than in permanent teeth (6.6% (3.95–10.9%)). The median DMFT score (IQR) was 1 (1–1.25), and the median deft score was 2 (1–4).

The association of dental caries with sociodemographic factors is presented in Table 2. Although the prevalence was higher among children attending government schools compared to private schools, no significant association was observed. In the study sample, the mother’s educational status demonstrated a stronger association with dental caries than the father’s educational status. However, none of the sociodemographic factors showed a significant association with dental caries.

The association of dental caries with various risk factors – oral hygiene, breastfeeding, sugar exposure, and ETS exposure – is presented in Table 3. Only 13 individuals (6.2%) in the study sample reported brushing their teeth twice daily. Breastfeeding during sleep time was common during infancy (87.7%; n = 185), while bottle feeding was reported by 36% of participants (n = 76). Among the bottle-fed children (n = 76), 16 (21.0%) used the bottle as a pacifier. Approximately 30% of the children (n = 64) had high sugar exposure, with a sugar score >15. During the antenatal period, the respondents exhibited lower levels of ETS exposure (54.5%; n = 115) than during the index period (64.9%; n = 137). The school neighborhood exposure (46.9%; n = 99) was higher than that of restaurants/ roadside stalls (42.2%; n = 89) or transit (bus or railway) points (59.7%; n = 126). However, none of the oral hygiene and dietary factors were significantly associated with dental caries. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure was most often due to smoking by the grandfather (24.2%; n = 52), followed by the father (11.8%; n = 25). Cigarettes were the most common form of ETS exposure (26.1%; n = 55), followed by beedi (17.5%; n = 37). Similar results were found for ETS exposure during the index period. Antenatal exposure was found to be significantly associated with an increased risk of dental caries (PR (95% CI): 1.44 (1.08–1.94)). No significant associations with dental caries were observed for other variables.

The prevalence of dental caries among children in school neighborhoods with ETS exposure was lower (43.4%) when compared to those without ETS exposure (54.5%). However, there was no statistically significant association between the two. The variables with a p-value <0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis (Table 4). The multivariate analysis, conducted using binomial regression, included the mother’s educational status, sugar exposure classified as low or high, and antenatal exposure to ETS as factors. Exposure to ETS in the school premises and during the index period were excluded due to high collinearity with ETS exposure during the antenatal period. In the multivariate analysis, only ETS exposure during the antenatal period showed a significant association with dental caries. The prevalence among those exposed to ETS during the antenatal period was 41% higher than among those not exposed. No other factors showed a significant association during the analysis.

Discussion

A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted among schoolchildren aged 5 to 10 years to assess the prevalence of dental caries and determine its association with ETS exposure. The overall prevalence of dental caries was 49.3% (42.5–56.1%), with a significantly higher prevalence in primary teeth (46.4% (39.8–53.3%)) than in permanent teeth (6.6% (3.95–10.9%)). Among the risk factors evaluated in the study, ETS exposure during the antenatal period was found to be significantly associated with an increased risk of dental caries (adjusted prevalence ratio (APR) (1.41 (1.05–1.90)).

The prevalence of dental caries in the present study was comparable to the pooled prevalence (49.6%) reported by Ganesh et al.4 and Janakiram et al.22 However, a few studies conducted in South India reported a higher prevalence than the present study.23, 24, 25 This difference could be attributed to geographical variation, epidemiological context and differences in age groups compared to other studies. As previously stated, the prevalence of dental caries in primary teeth was considerably higher in the current study. A systematic review evaluated the variation in childhood dental caries and reported that the prevalence of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth was similar in Asia (53% vs. 58%).26 However, this similarity was not reported in the 5 to 10 age group. The present study did not find any significant associations between sociodemographic factors and dental caries. A scoping review of risk factors in childhood dental caries reported that male gender, poor maternal education and low family income were commonly associated with dental caries.5 In the present study, gender and maternal education showed comparable results but were not statistically significant.

The dietary factors assessed in the study had no association with dental caries. Previous studies have consistently reported an association between dental caries and breastfeeding, bottle feeding and sugar exposure.27, 28, 29 There is extensive evidence supporting the role of sugar intake in dental caries. Although the present study did not find a significant association with sugar intake, the evidence is overwhelming and cannot be ignored. The lack of association between sugar intake and dental caries could be due to limitations in its assessment, specifically the use of 24-hour dietary recall which may inaccurately represent past sugar intake. Additionally, recall bias and inadequate sample size may have contributed to the lack of significant results. The present study evaluated various factors including brushing frequency, brushing by parents, brushing under parental supervision, and the use of fluoride toothpaste, but none were found to have a significant association with dental caries. Several studies have reported on the protective effect of oral hygiene on dental caries.23, 30 However, the present study did not find a significant association, which could be due to sampling variation and inadequate sample size. In addition, antenatal exposure to ETS was associated with a considerable increase in the risk of dental caries (PR: 1.44 (1.08–1.94)). No other variables showed a significant association with dental caries. When adjusted for maternal education and sugar exposure, antenatal exposure to ETS remained substantial, with an APR of 1.41 (1.05–1.90).

The findings of the present study are consistent with those of a systematic review conducted by Gonzâlez-Valero et al.15 In their meta-analysis, prenatal exposure to secondhand smoke increased the risk of dental caries in primary teeth, with a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.72 (1.45–2.05). Kellesarian et al.14 and Hanioka et al.31 also reported a positive association between antenatal exposure and dental caries in children. The findings of the present study support the hypothesis of previous systematic reviews. Tanaka et al.32 reported a similar association, with a PR of 1.43 (1.07–1.91). Other studies by Iida et al.,33 Tanaka and Miyake34 and Majorana et al.35 reported a comparable increase in the risk of dental caries due to prenatal exposure. Our results differed from those of Shulman,36 Tanaka et al.37 and Claudia et al.,38 who reported an insignificant association between the variables. However, in these studies, the lack of significance was marginal. Exposure to ETS during the antenatal period may occur due to the transfer of harmful chemicals through the placenta. Noakes et al.39 demonstrated impaired toll-like receptor-mediated immune function in neonates and infants, which increases the susceptibility to several infections. This could be one of the biological mechanisms leading to an increased risk of dental caries. Genetic polymorphisms, such as those found in the MSX1 gene, could play a mediating role between maternal tobacco exposure and dental susceptibility to caries.40 It has been reported that MSX1 can also cause alterations in developing teeth.41 The effects of tobacco exposure may be similar to those of chemical agents.42 Maternal exposure to ETS may alter the oral microbiome in a similar way to adult exposure.7 A systematic review concluded that maternal exposure to disinfectants and antibiotics may also alter the oral microbiome.43 Prenatal exposure to ETS may continue in the postnatal period, resulting in a cumulative increase in exposure.

In contrast to other studies, exposure to ETS during the index period did not have a significant effect on the prevalence of dental caries in the present study. Gonzâlez-Valero et al. reported a significant association between postnatal smoking and dental caries (pooled OR: 1.72 (1.45–2.05)).15 Hanioka et al.31 reported a significant association among the studies compiled in their systematic review, but did not provide a summary effect estimate. Based on the available evidence, it can be concluded that exposure to ETS during childhood is a significant risk factor for dental caries. The lack of association observed in the present study may be attributed to the low prevalence of smoking in India compared to other countries and the inadequate sample size.

Parental education is directly associated with family socioeconomic status, and dental caries have also been associated with these 2 factors.44 The present study examined the education levels of both father and mother. The findings of previous studies on the association between ETS and dental caries are comparable with the results of the present study.16, 31, 32 None of the participants in the present study belonged to a lower socioeconomic level. The recent outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic affected healthcare professionals, including dentists, and led to the development of numerous innovative strategies in clinical dentistry.45, 46, 47, 48 However, the study was conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic and since none of the children were affected, the relationship between COVID-19 and dental caries could not be evaluated.45, 46, 47, 48 The study participants had a high prevalence of household smoking (35.1% during the index period) compared to the national average of 19% (GATS-2).16 There could have been a differential recall bias regarding smoking exposure, as the caregivers of children with dental caries could have reported higher ETS exposure than those without dental caries.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study was the insufficient sample size, which may have contributed to a lack of association with several known factors. Additionally, due to the low prevalence of caries in permanent teeth, the study did not have sufficient power to analyze the association with caries in deciduous and permanent teeth separately. Another limitation was the assessment of ETS based on the participant recall, which did not allow for the assessment of cumulative exposure to ETS. The study also lacked objective measures, such as serum or urine cotinine levels, to validate its findings. To date, few studies in India have demonstrated an association between ETS and dental caries in children.30 The sample was stratified between government and private schools to ensure representation. The prevalence of dental caries was assessed using the standard WHO form to ensure standardization of assessment. The study also focused on an age group at high risk of dental caries and with mixed dentition. The prevalence of dental caries among schoolchildren in Nellore is comparable to the national average reported by systematic reviews. Further investigation is needed to understand the variation between dental caries in primary and permanent dentition. The Indian population has low awareness of the risk posed by ETS exposure for dental caries. To reduce the risk of dental caries, oral health education campaigns must propagate this message among parents and children.

Conclusions

The prevalence of dental caries among schoolchildren aged 5 to 10 was 49.6%. After adjusting for other factors, antenatal exposure to ETS contributed to a slight but significant increase in the prevalence of dental caries by 41%. However, the role of ETS exposure in dental caries requires further evaluation using cohort studies. The present study observed lower rates of brushing under parental supervision and using fluoride toothpaste. Interventions aimed at controlling these factors can further reduce the prevalence of dental caries.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Narayana Dental College and Hospital (approval No. NDC/IECC/PEDO/12-18/01). Consent to participate was obtained from the school authorities, parents, and families of the children.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.