Abstract

To synthesize previous findings on the prevalence of periodontal disease (PD) in the adult Vietnamese population, a search for peer-reviewed literature was conducted using the MEDLINE, PubMed and Scopus databases through January 10, 2022. Two reviewers individually assessed abstracts and full-text articles to determine their suitability for inclusion. Only English articles were included if their results described the prevalence of PD among the Vietnamese. Among 900 potential studies, 8 cross-sectional studies with 7,262 adult participants qualified to be included. We found that overall the prevalence of PD was 64.9% (95% confidence interval (CI): 45–81%), with very high heterogeneity across the observed prevalence estimates (Q = 1,204.8776; df = 7; p < 0.001; I2 = 99.42%). Further subgroup analyses stratified by age, location, sampling, study design, and region also revealed significant differences, with a higher prevalence of PD among (1) population-based studies, (2) participants aged ≥65 years, (3) participants with non-chronic diseases, (4) studies using the WHO, community periodontal index (CPI) and standard oral examinations, (5) studies conducted in Central Vietnam, and (6) studies using randomization sampling (p < 0.01) than in other populations. Sensitivity analyses validated the stability of the current findings. Within the limits of the available evidence, this meta-analysis showed a high percentage of Vietnamese adults suffer from PD. Nonetheless, the findings should be taken cautiously due to the limited number of published articles and the possibility of bias in the included research. More well-designed studies with larger sample sizes are thus required for further verification.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, inflammation, periodontitis

Introduction

Maintaining excellent oral health is not just about keeping our teeth healthy, but it is also about maintaining our overall health and well-being, as has been extensively proven in the literature. Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) expanded the definition of oral health by including the concept of well-being as “Oral health is a key indicator of overall health, well-being, and quality of life”.1 Gingivitis- and periodontitis-induced tissue deterioration are included under the umbrella term of periodontal disease (PD), which results in alveolar bone and tooth loss. Masticatory dysfunction and an adverse effect on the patient’s quality of life have been linked to PD.2 Even though oral diseases are generally avoidable, they are ubiquitous throughout life and have significant negative consequences for the health of individuals, groups, and society at large, with substantial social, psychological, health services, and economic impacts.3 A serious public health concern, periodontitis significantly raises morbidity and expenditures on dental healthcare, affecting around 14% of the world’s adult population in 2020.1 Although PD substantially influences one’s overall health and well-being, this disease has received just a fraction of the attention of dental caries in terms of public health approaches to disease management and prevention.

Unfortunately, many nations still lack the human, financial, and material resources necessary to fulfill the demand for oral health care services and a comprehensive program to provide universal access, particularly in developing countries such as Vietnam.4 The 2001 National Oral Health Survey showed the prevalence of PD amongst adults is exceedingly high. According to this survey, PD affected 97.5% of Vietnamese, and a staggering 91.8% of Vietnamese adults 45 years and older had gingivitis and PD.5 Over the last several decades, Vietnam has made significant strides toward improving public health. As a result of the significant burden of PD and its consequences for individuals and healthcare systems, the Vietnamese government has made a considerable effort to improve the oral health of its citizens; however, the results have fallen short of expectations.6 Moreover, a comprehensive public health strategy to prevent PD and enhance oral health is now in the early stages of development.

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review studies regarding PD in Vietnamese adults have been conducted. Therefore, it is critical to raise awareness of PD and understand the state of knowledge on the condition as a significant component of reorienting health services to improve periodontal health. For these reasons, we conducted a systematic review to critically and comprehensively determine the percentage of individuals in the Vietnamese community who have PD.

Material and methods

Protocol

An effective search and selection strategy was developed according to the principles and suggestions laid forth in the PRISMA Statement7 to guarantee that the review process was transparent and exhaustive.

Search strategy

We used a predetermined lexicon to conduct a comprehensive search up to January 10, 2022. In three databases comprising a gray literature database (MEDLINE, PubMed and Scopus), the language was confined to English. Consequently, there is a possibility for publishing bias to be introduced. Depending on the database, we used a combination of keywords, medical subject headings (MeSH), synonyms, and glossary terms to enhance our search results. Search terms included oral diseases (e.g., periodontitis, tooth loss, mouth cancer) and the relevant population (e.g., Vietnam, Vietnamese). Appendix 1 (available on request from the corresponding author) shows a synopsis of the search approach.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies were screened based on titles and abstracts. If an informed conclusion could not be reached based on this information, the entire article was examined. Any English-language observational research (such as a cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional study) was eligible if it met all of the following criteria:

– The original research was published in a peer-reviewed journal reporting outcomes on the proportion of PD in Vietnamese patients who reside in the country.

– Only studies in which a dental professional performed an oral/dental examination were included.

– The research included adult participants who were at least 18 years old.

Articles were ineligible if they satisfied any of the following criteria:

– Duplications were eliminated from the evaluation process.

– Experimental studies, as well as animal studies and editorial letters, reviews, commentaries, book chapters, and case studies, were excluded.

– Participants were an overseas Vietnamese population living outside Vietnam.

– Neither the whole text nor any relevant information could be retrieved.

There was no screening applied to the recruiting sites (e.g., care homes, hospitals, or communities) or the general health state of the participants in this study.

Study selection and data extraction

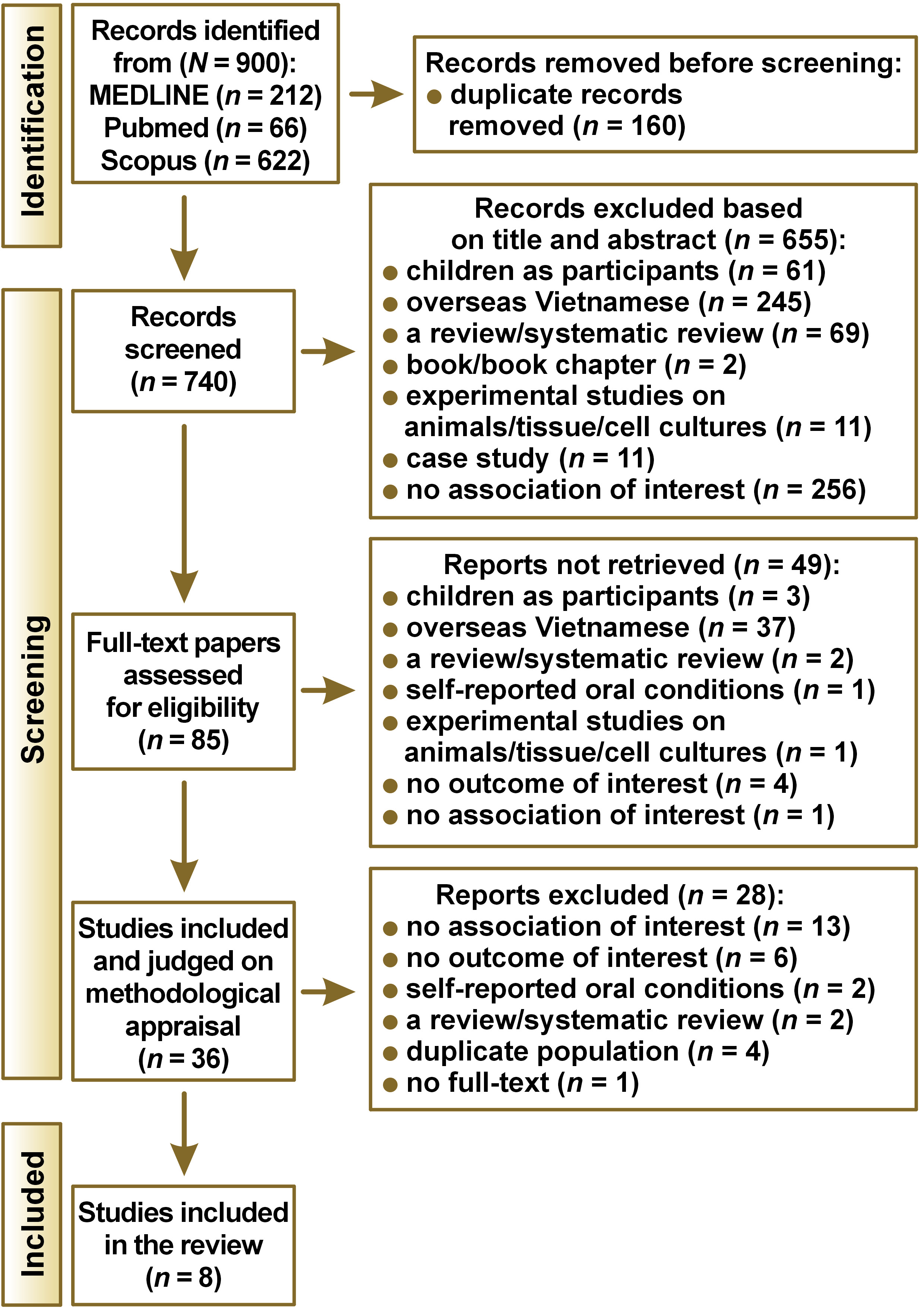

According to the PRISMA flow diagram, the selection process was carried out step-by-step (Figure 1). The following screening procedures were completed by two separate reviewers evaluating the original collection of articles (CTQV and QNP):

– First, duplications and publications written in languages other than English were ruled out.

– Second, the description in the abstracts was used to make further exclusions. Discarded articles were those that did not meet the criteria for inclusion. Full-text screenings were conducted where the information for inclusion and/or exclusion was not included in the abstract.

– Finally, the full texts of the remaining articles were scrutinized to avoid biased inclusion of studies, and those that did not meet the qualifying requirements were once again discarded.

Any disagreements between authors about whether a study was eligible were discussed and adjudicated by the third reviewer (DQT). Microsoft Excel 2019 was used to keep track of all of the chosen references for retrieval from the databases. Table 1 contains the information gathered from the data retrieval, which includes the first author, publication year, study design, geographical location (community or hospital), sample size, average age, gender, type of oral assessment, and population type (non-patient and patient participants).

Quality assessment

PNQ and CTQV independently evaluated the methodological quality of the included papers using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies. This scale evaluates three domains, including the representativeness of the investigated subjects, the comparability across groups, and the ascertainment of outcome and exposure. The overall score for a cross-sectional study was 8 points. The included studies were then divided into three categories: high (>7 points), moderate (4–6 points), and poor (0–3 points) in terms of overall quality scores.8 Any dispute between the two reviewers about the quality of methodology and evidence score of the included articles was adjudicated by DQT.

Statistical analysis

The primary finding of this study was the prevalence of PD among the Vietnamese adult population. For all analyses, we utilized RStudio Desktop, v. 2022.02.0 (https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop), together with the meta and metafor packages. Heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran’s Q-statistic and I2 tests. A fixed-effects model was used if there was no substantial heterogeneity identified (I2 ≤ 50%; p > 0.1); otherwise, a random-effects model was adopted. Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine the robustness of the overall estimates. We undertook subgroup analysis by areas, assessment, average age, regional differences, sampling, and non-patient and patient participants. Subgroup comparisons were statistically significant if the significance threshold was a p-value ≤0.05. To evaluate publication bias, funnel plots were used.

Results

Results of the search

A total of 900 potentially relevant articles were identified from all of the databases used in this study. Following the removal of duplicates, 740 results were analyzed further. Titles and abstracts were evaluated for research methodology, research site, participant, reporting on oral health status, and the method for evaluating the participants’ dental health. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, 85 studies required evaluation of their full text, of which 77 did not fulfill the selection criteria and were thus discarded. Ultimately, we explored eight selected original articles for inclusion in this review. Results of the systematic searches and details of the selection process are shown in Figure 1 and Appendix 2 (available on request from the corresponding author), respectively.

Findings

Table 1 summarizes the research characteristics of the studies included in the current meta-analysis. A total of 7,262 participants were included in the eight investigations, which comprised one nationwide study 5 and seven cross-sectional studies.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Two studies were performed in Central Vietnam,9, 10 five studies in Southern Vietnam,11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and one nationwide study in 14 provinces and cities, which in total represents 62 of the provinces over the whole country.5 All of the research was carried out between 1999 and 2020. Six of these studies were done in clinical departments of a hospital,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 while two utilized a population database to recruit participants.5, 9 Adults of various ages were involved in all studies, and among them, two investigations, exclusively including the elderly (≥60 years), were conducted.9, 11 To diagnose PD, a trained dentist who used a variety of criteria to determine the presence of this disease evaluated the patients, as described in Table 1. Standard criteria were used for the diagnosis and categorized into four groups: Community Periodontal Index (CPI),9 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the American Academy of Periodontology (CDC/AAP) case definitions for surveillance of periodontitis,13, 14, 15 Oral health surveys: basic methods of WHO,10, 11, 16 and a standard oral examination.12

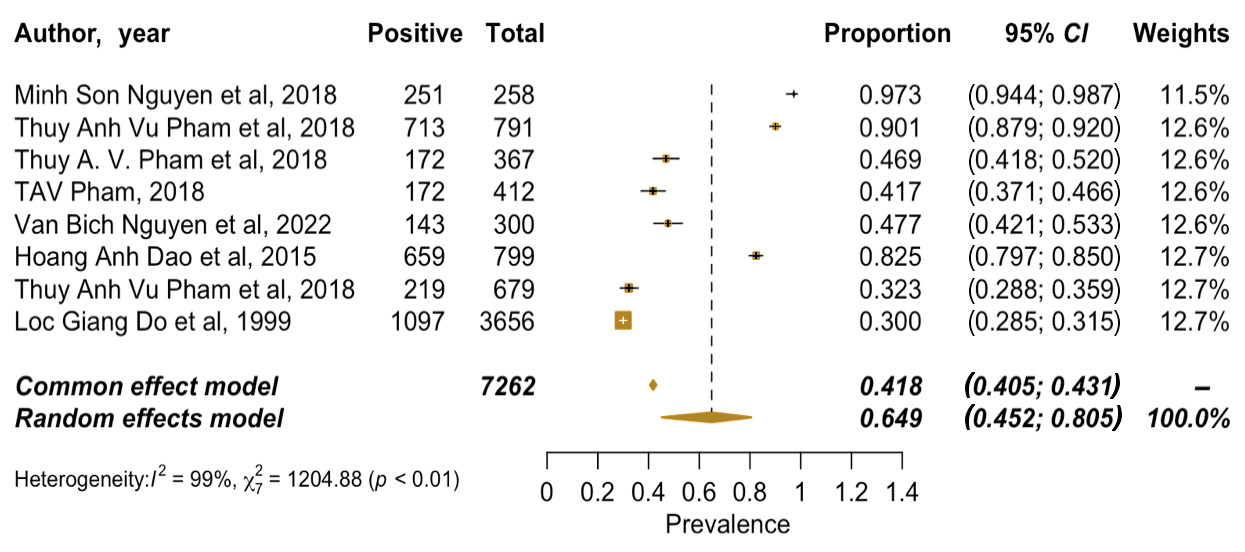

Prevalence estimates and heterogeneity

Figure 2 presents the findings of the meta-analysis. The results of a random-effects meta-analysis revealed that the pooled estimate of PD was 64.9% (95% confidence interval (CI): 45–81%). Cochran Q was significant (Q = 1,204.8776; df = 7; p < 0.001), demonstrating heterogeneity among the prevalence estimations, while the I2 statistic was 99.42%, indicating very high heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis

Areas

In a subgroup analysis of the eight studies of 3,426 periodontal cases, 78.0% (95% CI: 37.7–95.4%) were identified in the community, and 60.1% (95% CI: 35.6–80.4%) were diagnosed in the hospital. There was high heterogeneity between studies (p < 0.01; I2 = 99%).

Assessment

In the subgroup analysis using assessment tools for PD, 3 studies reported significant differences between the CDC/AAP (40.4%; 95% CI: 13.0–75.4%) and the other tools, including WHO, CPI, and standard oral examination (77.5%; 95% CI: 51.5–91.8%), with high heterogeneity (p < 0.01; I2 = 99%).

Average age

Over 65-year-old individuals were more likely to develop PD than those under 65 years old (94.5%; 95% CI: 82.8–98.4% vs. 47.5%; 95% CI: 30.9–64.6%), with high heterogeneity (p < 0.01; I2 = 99%).

Regional differences

The meta-analysis demonstrated that the proportion of PD in Central Vietnam (92.6%; 95% CI: 67.9–98.7%) was significantly higher than its proportion in both general (30.0%; 95% CI: 29.0–32.0%) and Southern Vietnam (54.5%; 95% CI: 28.5–78.3%). There was evidence of high heterogeneity across the studies (p < 0.01; I2 = 99%).

Sampling

The percentage of periodontal cases yielded by randomization sampling was more significant than participants acquired through convenience sampling (78.0%; 95% CI: 37.7–95.4% vs. 60.1%; 95% CI: 35.6–80.4%), with high heterogeneity (p < 0.01; I2 = 99%).

Non-patient and patient participants

Pooled results from 8 studies indicated that a lower proportion of patients had PD among those with chronic diseases (40.4%; 95% CI: 13.0–75.4%) compared with non-chronic diseases (77.5%; 95% CI: 51.5–91.8%), with high heterogeneity (p < 0.01; I2 = 99%).

Quality assessment

Table 1 and Appendix 1 (available on request from the corresponding author) depict the study quality appraisal of the included studies. The general quality of the included studies was moderate, with total ratings ranging from five to seven out of a possible eight. The most significant drawbacks of the included studies were selection bias, which occurred since the majority of the studies were not randomized, were done using convenience and purposeful samples, and did not give all of the necessary information for statistical sample size calculation, hence, lacked transparency and completeness.

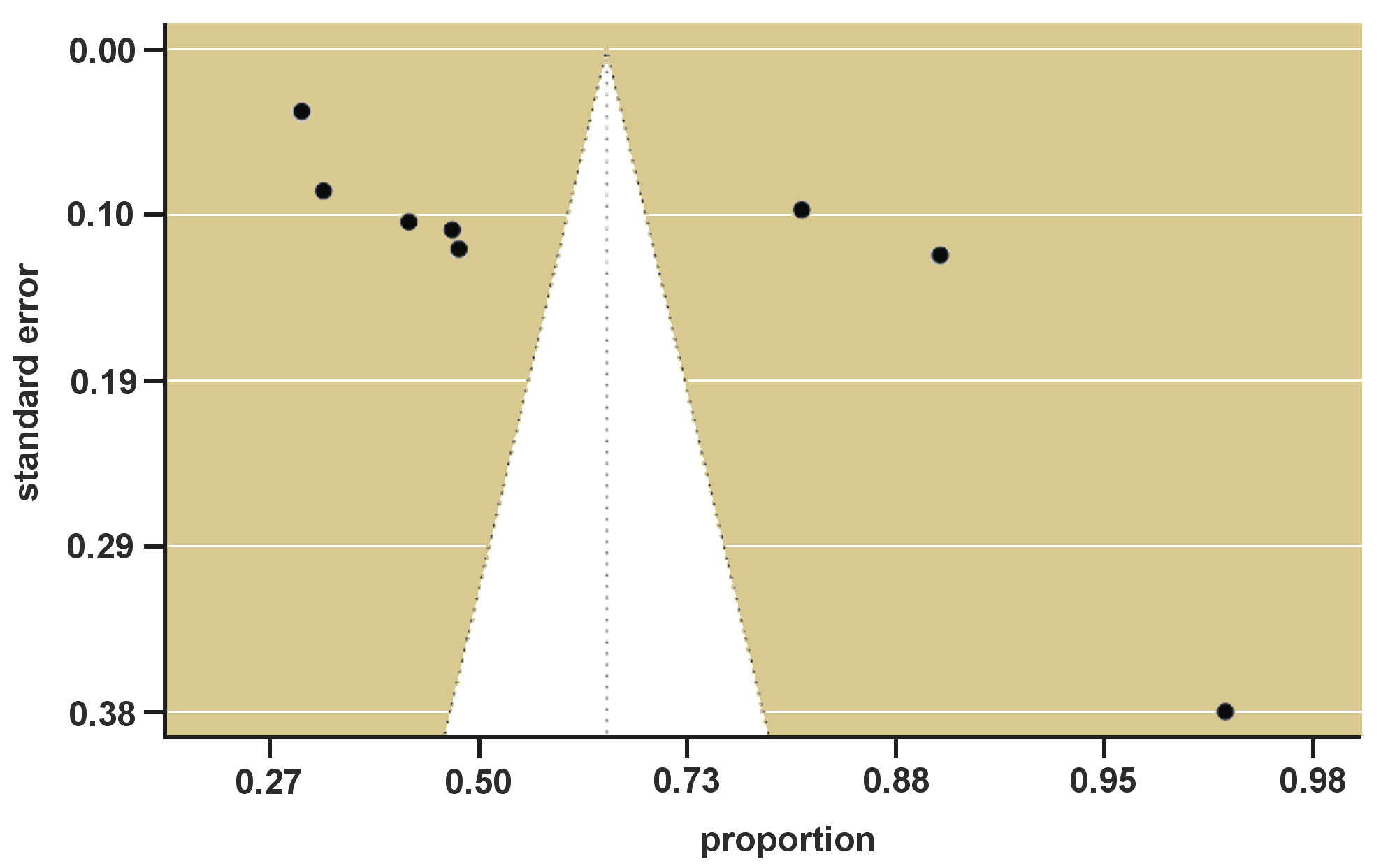

Publication bias

As shown in Figure 3, the funnel plot for the primary outcome, PD, appeared somewhat discordant with the results of the meta-analyses. In this case, however, the estimate of publication bias may be erroneous due to a lack of an appropriate number of included studies.

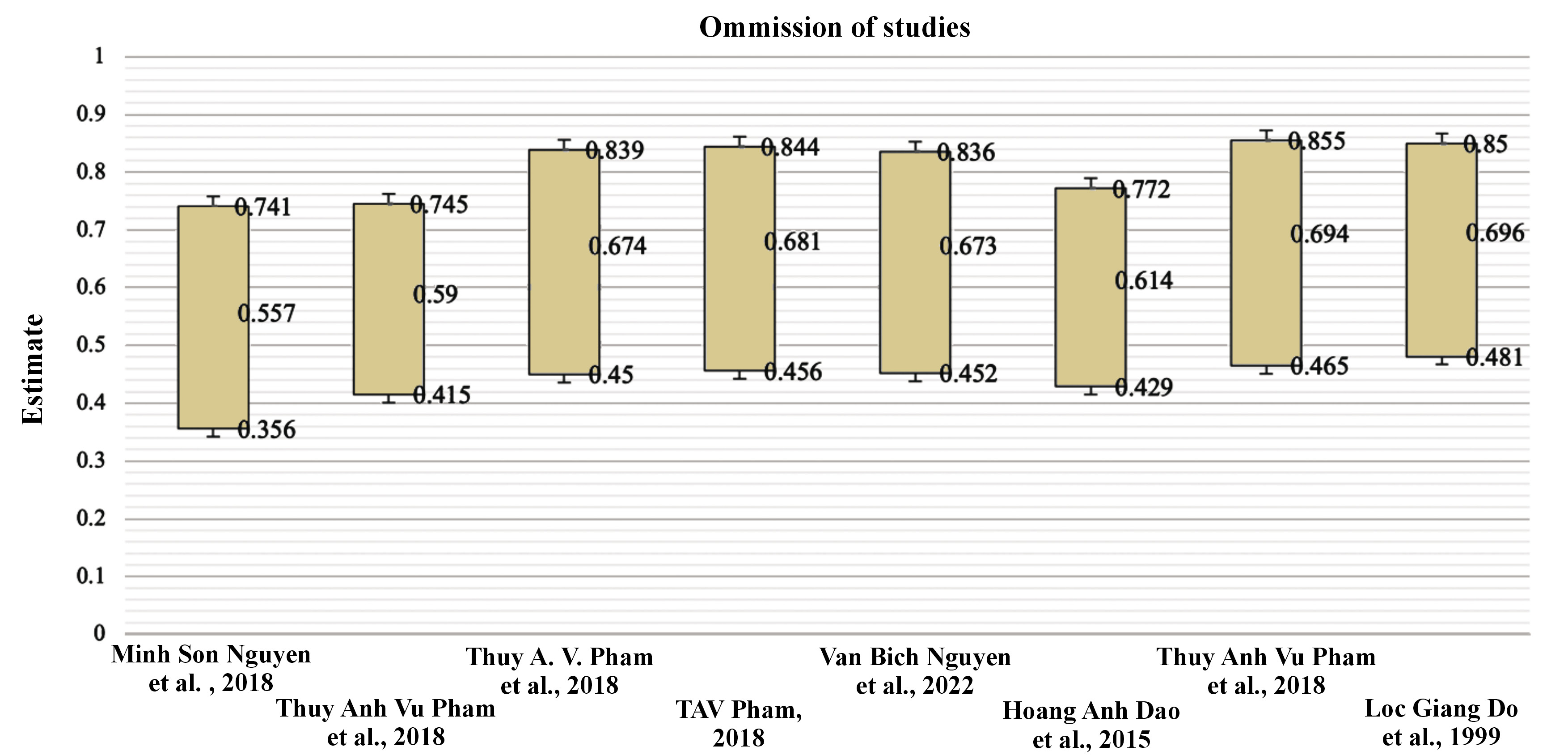

Sensitivity analysis

To determine the stability of the pooled prevalence of our key outcome, each study was eliminated one at a time from the other (Figure 4). Excluding any one of the studies was shown to not significantly affect the results, indicating that the findings are credible and there is a high prevalence of PD among the Vietnamese population.

Discussion

According to a WHO report in 2020, more than a billion people are afflicted by PD globally, occurring in both developed and developing nations.1 Recognizing that PD is avoidable, there is undoubtedly a pressing need for a more global effort to implement effective diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic strategies to reduce the burden of PD on individuals, nations, and the globe.17 Therefore, we did this systematic review to synthesize the existing research to assist us in better understanding the prevalence of PD among the Vietnamese adult population.

As a result, a total of 7,262 individuals from eight cross-sectional studies published after the year 1999 were pooled for the first time in this meta-analysis to examine the prevalence of PD in the Vietnamese population. According to the random effect size estimation, the pooled prevalence of PD in this meta-analysis was 64.9%. This estimate was greater than the prevalence of PD in Americans (47.2%),18 Indian adults (51.0%),19 and the global prevalence rate of 20–50%.20 There is a disparity in prevalence estimates between this study and the American18 and Indian studies,19 which might be attributed to the differences in methodological quality. Moreover, our results demonstrate that the percentage of PD was considerably lower among individuals who were chronic patients and were receiving treatment at the hospital, studies utilizing the CDC/AAP evaluation and convenience sample, age ≤65 years, and located in Southern Vietnam.

Like many chronic illnesses, PD is a multi-factorial disease with numerous contributing causes, including modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.21 From the perspective of public health on a national level, we consolidated several causation hypotheses that may serve as proliferation causes in the development of PD to the expansion of this disease across Vietnam. However, to confirm whether these hypotheses are the genuine causes of PD, they must be explicitly investigated using high consensus criteria for quality research designs and well-validated metrics for the Vietnamese population, which are currently unavailable.

First, among modifiable risk factors for PD, smoking is the most important, and it continues to be a public health concern in many countries, including Vietnam. Several studies have reported that destructive PD is at least five to six times more likely to occur in smokers than in nonsmokers.22 Despite the Vietnamese government’s efforts to eradicate this epidemic, almost half of adult males in Vietnam are now smoking.23 Moreover, a high number of individuals are exposed to second-hand smoke.24

Second, sugar consumption, a foundational element of human development, has been identified as a critical risk factor for the development of PD.25 Vietnam has been undergoing a nutrition transition, including increasing the availability of sweets and sweetened drinks over the last few years.26 Moreover, the National Oral Health Survey in 2019 identified numerous notable changes, as remarkable economic development resulted in considerable changes in food consumption, particularly sugar-sweetened foods.27 The rising consumption of sugar-sweetened foods and beverages among Vietnamese has become a significant public health problem, with daily sugar intake about double the WHO recommendation (25 g).28

Third, innumerable research has shown that diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease increase the susceptibility to oral infections, especially PD.21 Among the Vietnamese population, both of these illnesses were significant contributors to the burden of chronic non-communicable diseases, with the number of persons with diabetes in Vietnam being approximately 5.76 million. In contrast, cardiovascular disease accounted for 31% of all fatalities in 2016.29

Forth, PD is one of several ailments whose prevalence increases with an accelerated aging condition. The aging of the world’s population is a worldwide phenomenon expected to have profound social transformations in the 21st century30 as a consequence of a dropping fertility rate and longer life expectancies. Vietnam has one of the oldest populations among Southeast Asian nations.31 Since PD is a frequent oral health concern among the elderly, our results have gained prominence as a serious public health issue in Vietnam.

Finally, for many people in underdeveloped nations, the expense of treating oral disorders is prohibitive. Thus, they avoid treatment,32 and people in poor socio-economic classes are more likely to suffer from dental disease, according to specific epidemiological research.33 With approximately 97 million people, Vietnam is a lower-middle-income nation.34 The lack of governmental funding for dental treatment in Vietnam means that many Vietnamese citizens must make tough financial decisions regarding getting dental care. Therefore, economic challenges may have a detrimental impact on the quality of oral health, and poor oral health can have a negative impact on overall health.35

Limitations and strengths

In this review, there are certain limitations:

– The majority of the studies were done in a hospital context or healthcare setting, which led to selection bias and over-representation of certain groups. The findings are difficult to extrapolate to the prevalence of PD among Vietnamese communities.

– All the research included in this meta-analysis used a cross-sectional study design, which insufficiently demonstrates ability, and hence, no causal conclusions could be drawn.

– The combined indicators were not comprehensive because of the small number of included papers, which resulted in significant heterogeneity among studies, and potential bias might exist. Therefore, an additional investigation was required.

– We discovered high heterogeneity among studies, which may be due to differences in methodological features, such as various ways of assessing PD.

– There is a lack of consistency in study designs, the definitions of PD, procedures used for disease detection and measurement, and criteria used for subject selection, which substantially restricts the interpretation and analysis of the PD data from the included studies.

– We only included peer-reviewed English-language articles, which may have resulted in the omission of several pertinent research studies, such as the National Oral Health Survey of Vietnam 2001 and 2019.

Accordingly, given the limitations discussed above, the outcomes of this meta-analysis must be confirmed by further well-designed studies from multi-centers with a larger sample size before they can be considered conclusive.

Compared to single-study approaches, our findings have aggregated the most up-to-date evidence to provide more reliable estimates on the percentage of adult patients in Vietnam who have PD. This was achievable since our outcome measure was more standardized, thanks to dental and medical specialists. Our meta-analysis also draws attention to the dearth of literature regarding factors that may contribute to PD in Vietnamese adults. Despite the comprehensive nature of our search technique, we did not summarize the relevant factors that emerged from the included articles. Therefore, future meta-analysis studies should thus focus on the risk factors for PD in adults, particularly those with long-term health conditions. This will help assess the efficiency of PD prevention and treatment actions that use existing risk approaches to minimize the scale of PD and other chronic diseases. Furthermore, raising awareness about PD is a significant public health concern in Vietnam for non-communicable diseases.

Conclusions

The recent pooled analysis of prevalence studies demonstrates that adults with PD are common in Vietnam. Nonetheless, our findings should be taken cautiously due to the small number of publications and the possibility of bias in the included studies. Thus, we urge that further research with rigorous assessments of the prevalence of PD be conducted to validate our results.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets and all supplementary materials generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.