Abstract

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is defined as an idiopathic orofacial pain with intraoral burning or dysesthesia. This systematic review aimed to analyze the scientific literature with regard to the effectiveness of placebo therapy in patients with BMS. A literature search was conducted through the PubMed-indexed journals within MEDLINE®, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Trip databases from their inception to May 31, 2022. The search terms were defined by combining (medical subject headings (MeSH) terms OR keywords) “burning mouth syndrome” AND (MeSH terms OR keywords) “placebo”. Methodological quality assessments were performed utilizing the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tool to attribute scores from 1 to 11 to the selected studies. The literature search, study selection and data extraction were carried out by 2 authors. Disagreements between the authors were resolved by the 3rd author, if necessary. A total of 44 articles met the inclusion criteria. After assessing full-text articles for eligibility, 20 articles were excluded. Consequently, 24 articles were retained. A total of 21 studies included in this systematic review had a low score of bias. In 13 studies, a positive response to placebo was noted. Among them, 7 showed a placebo response indistinguishable from active treatment. These changes were more pronounced in patients receiving placebo therapy compared to active treatment in 1 study. Placebo therapy may occasionally be beneficial and ethically acceptable for patients with BMS. To get stronger evidence for the use of a placebo, future studies with standardized methodology and outcomes are required.

Keywords: pain, trigeminal, stomatodynia, placebo effect

Introduction

According to the International Classification of Orofacial Pain, burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is defined as “an idiopathic orofacial pain with intraoral burning or dysesthesia recurring daily for more than 2 h for over more than 3 months. It has no identifiable causative lesions, and it is manifested with and without somatosensory changes”.1 It has a prevalence of 0.1–3.9% and appears to be more frequent in females, especially in post-menopausal women between the age of 50 and 70 years.2 Burning mouth syndrome is accompanied by normal clinical or laboratory findings.3 Burning pain may affect multiple sites within the oral cavity, but most commonly affects the tongue.4 Investigators have proven that this syndrome “may exist coincidentally with other oral conditions”.5 The use of the term “syndrome” is explained by the co-occurrence of BMS with other subjective symptoms.6 Stomatodynia is the main indicator of this condition. It can be accompanied by other sensory disorders, such as xerostomia and complaints of altered taste with or without the presence of salivary hypofunction.7 There is also no clear consensus on the exact etiopathogenesis of this syndrome. However, it is often considered idiopathic. Additionally, no definitive remedy is available and most of the treatment methods produce unsatisfactory results.3 Given the complex etiopathogenesis of BMS, numerous therapeutic regimens have been proposed.3 Treatment regimens should be adapted to each individual and a multidisciplinary approach is recommended.8 In recent years, a number of therapeutic options have been developed by exploiting stem cells, opening up an important therapeutic possibility for this syndrome.9, 10 Treatments can consist of pharmacological agents (topical or systemic medications), cognitive behavioral therapy, and complementary or alternative medicinal therapies to soothe the patient’s pain.11 However, no therapeutic modality is considered the gold standard, and these treatments are not considered to be reliable and effective.3 A placebo has thus been suggested as a solution for BMS.

A placebo is an “inert substance”, usually a carbohydrate tablet or something that closely mimics the active treatment.12 The term “placebo” has Latin origins. Etymologically, it means “I shall please”.13 It was first introduced into the medical field during the 18th century as a medicine responding to a patient’s expectations without providing any real concrete outcomes.13 Placebos have the potential to alleviate many medical conditions. The healing result of non-specific therapy increases a patient’s belief in the placebo effect.13

Several systematic reviews have assessed the efficacy of various treatments for BMS,11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 but to the best of the authors’ knowledge, only 1 study reviewed the placebo effect in the management of this syndrome.24

This study aimed to perform a systematic analysis of the literature regarding the effectiveness of placebo therapy in patients with BMS, evaluating short- and long-term outcomes.

Material and methods

Study design

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure transparency and comprehensiveness.25 The search protocol was specified in advance and registered with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, No. CRD42021231242).

Focused PICOS question

The criteria for including studies in this systematic review were determined according to the Participant–Intervention–Comparison–Outcome–Study (PICOS) design scheme (Table 1). Numerical scores were used to standardize the format of the questionnaires, such as mono-dimensional pain scores including a numeric rating scale (NRS), visual analog scale (VAS), face scale, present pain intensity (PPI), or multi-dimensional scores involving the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ).

Search strategy

An electronic search was performed using 4 databases: the National Library of Medicine (MEDLINE®, PubMed), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Scopus, and Trip. The search terms used were a combination of (medical subject headings (MeSH) terms OR keywords) “burning mouth syndrome” AND (MeSH terms OR keywords) “placebo”. No language or time restrictions were applied. The last electronic search was performed on May 31, 2022. It was enriched by hand searches and citation screenings. All reference lists of the selected full-text articles and related reviews were scanned for additional studies.

Screening and selection

Three reviewers (DC, RBK and MK) independently screened the titles and abstracts obtained during the 1st search. If a publication did not meet the inclusion criteria, it was excluded after agreement between all reviewers. Any disagreement between the 3 reviewers was resolved after a discussion. Full texts of the eligible articles were examined by the reviewers. When necessary, the original authors were contacted to obtain additional information.

Data extraction

Data extraction was independently conducted by 2 reviewers (DC and MK). Data extraction forms were subsequently compared between the researchers and a final form was obtained. The authors of eligible articles were contacted via e-mail for clarification in cases of doubt or missing data. In crossover studies, the 2 periods (before and after the crossover) were used.

Data recording

The design, sample size, intervention type, and control of each study were analyzed and summarized according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) protocol:

– methods: study design, location/setting, recruitment period, and follow-up time;

– participants: inclusion and exclusion criteria, demographics and number of participants;

– intervention: details regarding the type of BMS treatments and types of placebo;

– outcome: pain.

Risk of bias in the included studies

Two reviewers (DC and MK) independently performed a quality assessment using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tool, specifically the checklist for randomized controlled trials (RCTs).26 The checklist is a 13-item appraisal consisting of the following areas: (1) randomization component, (2) allocation concealment, (3) treatment group similarity at baseline, (4) blinding of participants, (5) blinding of personnel, (6) blinding of outcome assessors, (7) groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest, (8) follow-up, (9) intention to treat, (10) similar outcome measurements, (11) reliable method of outcome measurements, (12) statistical analysis, and (13) trial design. These items were scored as either “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, or “not applicable”. Two reviewers (DC and MK) independently evaluated the included studies with discrepancies handled through discussion. If discrepancies could not be resolved through discussion, the third reviewer (RBK) was involved to reach a consensus.

Three levels of bias were determined26:

– high risk of bias: “yes” scores below 49%;

– moderate risk of bias: “yes” scores between 50% and 69%;

– low risk of bias: “yes” scores higher than 70%.

Results

Search results

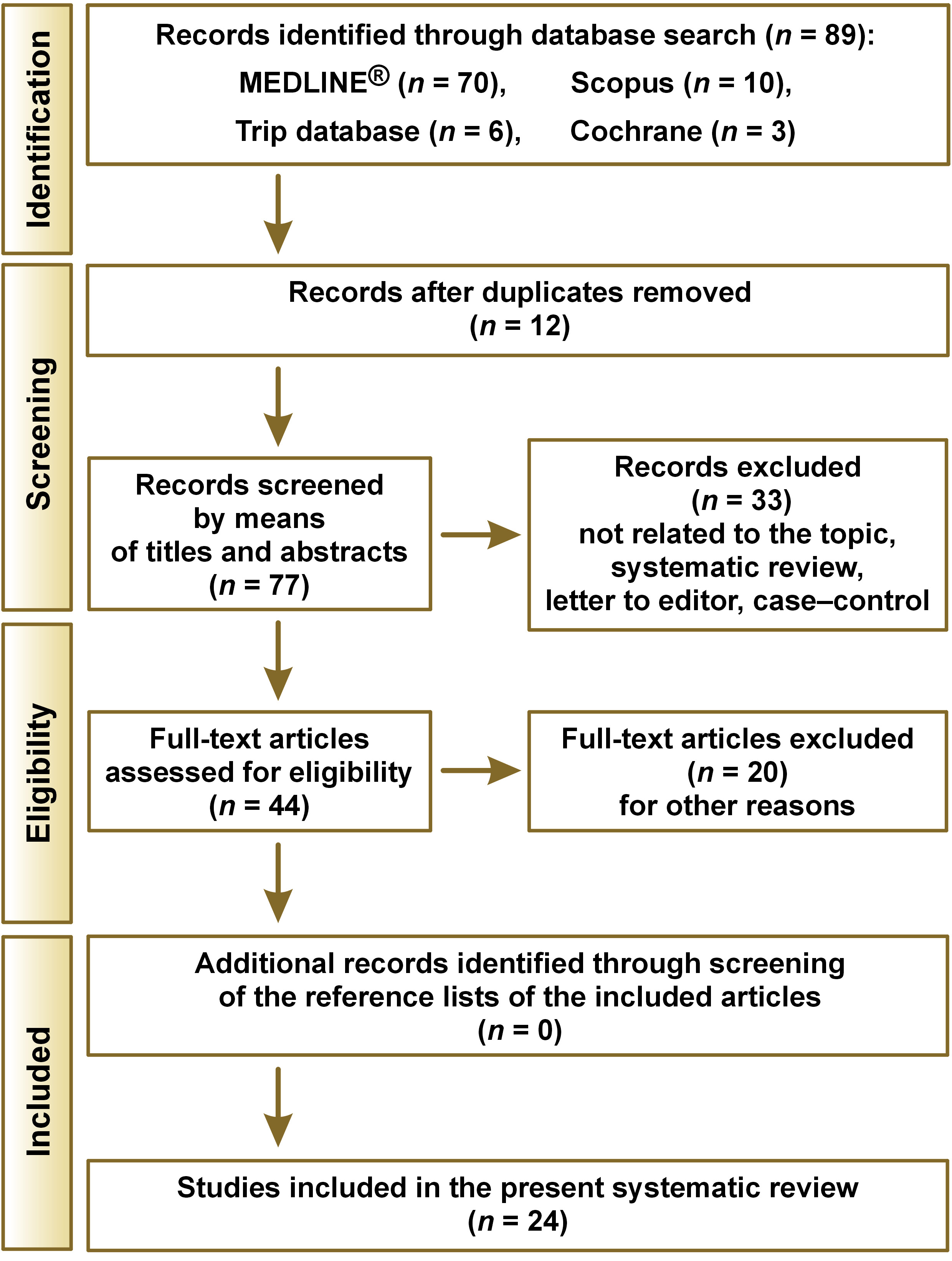

The search process yielded 89 articles, of which 12 were duplicates. Among the 77 remaining papers, 33 were excluded after a review of the title and abstract. After assessing 44 full-text articles for eligibility, 20 were excluded for other reasons.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Consequently, 24 articles were included in the review.47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 The search results are presented in Figure 1.

Study selection and characteristics

The retained studies were assessed for methodological quality (Table 2). A total of 21 studies included in this systematic review had a low score of bias.47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69 Three studies had a moderate score of bias.60, 61, 70 The final bias scores ranged from 53.8% to 100%.

Table 3 details the main characteristics and methodology points of the retained studies. The studies were published between 199957, 63 and 2020.52, 64, 66 They were conducted in Spain,49, 50, 52, 53, 67, 69 Croatia,64 Serbia,70 Italy,48, 55, 56, 57, 60, 61 Brazil,54, 58, 59, 65 Germany,68 France,62 and Finland.63 Three studies failed to report where they were carried out.47, 51, 66 The number of treated participants varied from 2055, 68 to 192,60 with a wide range of ages, varying from 2261 to 8968 years. All BMS participants were appropriately defined as having chronic pain for more than 3, 4 or 6 months with normal oral mucosa.

Randomization was applied in 22 studies (Table 2).47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69 All 24 studies were controlled clinical trials, involving 2 triple-blind studies (participant, caretaker and assessor),47, 55 17 double-blind studies,48, 49, 50, 51, 54, 56, 57, 58, 59, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69 and 2 single-blind studies (participants).52, 61 Four of the clinical trials had a crossover design (Table 3).49, 55, 59, 70 All studies reported data on items 7 (i.e., groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest), 8 (i.e., follow-up), 9 (i.e., intention to treat), 10 (i.e., similar outcome measurements), 12 (i.e., statistical analysis), and 13 (i.e., trial design; Table 2). Twenty-two studies with a treatment duration between 10 days and 3 months were categorized as short-term assessments.47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 The remaining 2 studies performed long-term assessments of 6 months.69, 70 At the end of the intervention, follow-up was reported in 8 studies,48, 52, 54, 60, 61, 62, 65, 66 ranging between 1 month and 1 year (Table 3).

Visual analog scale was the primary assessment tool for measuring pain intensity. It was used in 22 studies.47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 59, 60, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 Supplementary assessment tools, such as MPQ,48, 52, 58, 63 NRS,66 PPI,58 numerical scales,62 and face scales54 were also used to evaluate pain (Table 3). Secondary outcome assessments were performed to assess the quality of health, anxiety, depression, and quality of sleep using patient-reported questionnaires, including the 36-item short form survey,52 oral health on quality of life,49, 52, 53, 67 Crown-Crisp Experimental Index,58 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,70 Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale,53, 55, 56, 67, 70 Beck Depression Inventory,51, 63, 68, 70 psychometric Symptom Checklist-90-R,52 Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale,55 Epworth Sleepiness Scale,55 xerostomia severity test,49, 53 salivary flow-rate,68 taste test,68 and smell test.68 Quantitative assessments of pain intensity were performed in 17 studies.48, 49, 50, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 59, 62, 63, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 Functional improvement was quantitatively assessed in 7 studies (Table 4).47, 51, 57, 58, 60, 61, 65

Placebo effects in burning mouth syndrome

Although the placebo was administered in the same way as the active treatment in all of the studies, its composition was noted in only 13 (54.2%) studies.48, 49, 50, 51, 54, 57, 59, 60, 61, 67, 68, 69, 70 The most commonly used placebo was cellulose.50, 51, 59, 60, 61, 70 The placebo pill in one study contained cellulose as the primary ingredient and dicalcium phosphate, microcrystalline cellulose, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, silicon dioxide, vegetable magnesium stearate, and shellac/stearic acid as secondary ingredients.48 Other placebo formulations included ingredients such as water and dye,67 lactose monohydrate,68 magnesium silicate,54 lactose,69 and hydrogen chloride (HCl).57 Valenzuela et al.49 applied water, hydroxyethyl, sorbitol, potassium sorbate, sodium metabisulfite, food coloring, and chamomile aroma as a gel. Three studies confirmed that the placebo matched the treatment arm with respect to shape, taste, smell, and color.47, 69, 70 In 8 other trials, the authors mentioned that the placebo was identical-looking to the treatment.48, 49, 51, 54, 59, 61, 62, 67 Silent/off laser therapy in contact with the mucosa was applied as a treatment in 5 studies (Table 3).52, 53, 64, 65, 66

In 13 studies, a positive response to the placebo was noted.48, 54, 55, 59, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 Moreover, in 7 of these studies,48, 59, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 the placebo response was statistically indistinguishable from the active treatment (Table 4). These changes were more pronounced in patients receiving a placebo compared to alpha lipoic acid (ALA) when the treatment was administered after the placebo during a crossover trial.59 Carbone et al.48 found that pain significantly decreased in the placebo group at the end of 4 months of follow-ups compared to the treatment group. However, in one study, patients treated with silent/off laser therapy had a recurrence of the burning sensation.66

Discussion

Our systematic review included 24 RCTs investigating the placebo effect in BMS. Randomized controlled trials are widely considered the most rigorous method for evaluating treatment efficacy or preventive interventions.71 In fact, 87.5% of the included studies had a low risk of bias. It is known that systematic reviews can be affected by bias at the level of individual studies.72 For this reason, an assessment of the validity of these studies was a crucial step when conducting this systematic review.73 If bias is ignored, the true effect of the intervention may be overestimated or underestimated.72 The main result in 7 of the studies was that treatment with a placebo produces a response that may be as large as the response to active drugs.48, 59, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 In 6 RCTs, the placebo arm showed a positive response but was less pronounced than in patients receiving active treatment.54, 55, 61, 68, 69, 70

Burning mouth syndrome is one of the most difficult conditions facing oral health care professionals due to its variation in clinical manifestations.3 Disagreements arise with regard to whether this condition should be considered a disease, disorder or syndrome. However, no sufficient data is available to justify any modification in taxonomy.7 Burning mouth syndrome has a negative impact on a patient’s life since it is always accompanied by pain.5 Pain levels were the principal outcome in the patients of the included studies. They were evaluated using many assessment tools. Visual analog scale, which is a uni-dimensional measurement for pain intensity was most commonly used, especially in diverse adult populations.74 McGill Pain Questionnaire was used in a few studies not only to describe the pain intensity but also the sensory, affective and evaluative aspects of pain. It is a multi-dimensional questionnaire designed to measure pain and its qualities in adults with chronic pain.74

There is no consensus on how to treat BMS.3 Consequently, treatment modalities based on a patient’s symptomatology often lead to unsatisfactory results. A recent systematic review11 concluded that the effectiveness of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments remains low. The latter should be tried first to manage BMS due to their low side effect profiles. It is important to mention that the key to treatment success depends on the following number of issues that must be solved: correct diagnosis, confirmation of diagnosis, patient’s acceptance, patient’s understanding of the likely clinical course, patient’s participation in the elaboration of a treatment strategy, compliance, positive feedback during treatment, and ongoing interest of the clinicians.75 Building trust and reassurance with patients is essential in the management of BMS.3 Moreover, affected individuals should have a realistic understanding of the probability of being cured. The impact on a patient’s attitude often results in long-term beneficial effects. The practitioner should meticulously investigate the patient’s family, medical, dental, and personal history. He should also carefully interpret the data obtained from various physical and laboratory tests. In cases of underlying local, systemic or psychological factors, treating or eliminating these factors is crucial in the therapeutic process.3

A placebo can be of great use in reducing the burning and associated symptoms in patients with BMS. Placebo analgesia “is recognized as a positive response to the administration of a substance known to be inert and to have no analgesic action”.76 However, it is strongly thought to be a potent painkiller by the patient.76 Current clinical pharmacologic research relies on the superiority of treatment over placebo.76 It has been confirmed that the overall response to treatment is the result of the specific effect of the treatment and the effect of the context in which the treatment is given. Placebo interventions are designed to stimulate a therapeutic context, affecting the patient’s brain, body and behavior.77 This systematic review revealed that a placebo may be effective in reducing pain caused by BMS.48, 59, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 In addition, these studies reported a short-term assessment of the placebo effect. The reduction in symptoms was still evident 2 months after the end of the intervention.48 Many mechanisms are involved in producing the placebo effect, such as expectations, conditioning, learning, motivation, memory, somatic focus, reward, anxiety reduction, and meaning.77 Recent advances in placebo research and neuroimaging have shown that the placebo effect is a real neurobiological phenomenon. Placebo analgesia is regulated, at least in part, by endogenous opioid mechanisms and results in the active inhibition of nociceptive activity.78 Nevertheless, no placebo effect was observed in 11 studies, and an improvement in the test group was significantly greater than that in the placebo group in 6 RCTs.54, 55, 61, 68, 69, 70 Thus, it is not inherent that patients with BMS will feel better in response to the treatment with a placebo, particularly in the case of subjective outcomes, such as pain. Greene et al.76 suggested that a third “no treatment” waitlist control group should be included in future RCTs. It would allow differentiation between the natural course of symptoms and a genuine placebo effect. However, whenever treatment is withheld, ethical questions arise. The use of placebo controls in RCTs is ethically acceptable in 4 conditions: “(i) when there is no proven effective treatment for the condition under study; (ii) when withholding treatment poses negligible risks to participants; (iii) when there are compelling methodological reasons for using placebo, and withholding treatment does not pose a risk of serious harm to participants; and more controversially, (iv) when there are compelling methodological reasons for using placebo, and the research is intended to develop interventions that can be implemented in the population from which trial participants are taken, and the trial does not require participants to forgo treatment they would otherwise receive”.71 The methodological reasons are important to ensure the ethical use of placebo controls in these last 2 controversial conditions.71 In addition, a no-treatment waitlist control group in which patients eventually receive active drugs raises ethical questions similar to those connected with the use of placebo arms in RCTs. In both cases, an institutional review board would need to weigh the potential benefit of the scientific knowledge to be gained against the potential harm that could be derived from withholding active treatment. In case of disorders such as BMS, for which there is no standard of care, the inclusion of a no-treatment waitlist control group may be ethically acceptable.24 Nevertheless, close attention should be paid to ensure that basic ethical principles are respected when placebo therapy is prescribed.79

Limitations

The present systematic review has some limitations. The first limitation concerns the sample size which differs between included studies. The second limitation is related to the duration of therapy. Patients were followed up for a short period of time, whereas the pain occurring in BMS is chronic. Future studies should last more than 3 months. The third limitation concerns the definition of clinically significant outcome. Although VAS was used in almost all the studies, this tool was applied in different ways. The 4th limitation is related to the placebo control which varied depending on the treatment used (laser therapy, for example). The 5th limitation concerns the definition of BMS, which is still lacking.3 It is worth noting that there is an urgent need to give an exact and universally accepted definition of this syndrome. Despite these limitations, the magnitude of the placebo response in BMS appears to be quite robust.24 Future RCTs investigating BMS would benefit from larger sample sizes, adequate follow-up periods and the use of a standard placebo. With respect to reporting data, we suggest that in future studies all available data should be reported, particularly VAS data, so that comparisons will be simpler.

Conclusions

Placebo therapy can sometimes be beneficial and ethically acceptable. The placebo effect found in this systematic review represents a significant challenge for future RCTs evaluating therapies for BMS. To obtain stronger evidence for placebo use, such trials should follow a standard protocol. An adequately long follow-up period must be established to discern if the treatment is more effective than a placebo.

Highlights

- • Key finding: Placebo may be effective in reducing pain caused by BMS.

- • Clinical implication: Placebo can be used as a treatment for BMS in some cases, especially since there is no gold standard treatment for this syndrome.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.