Abstract

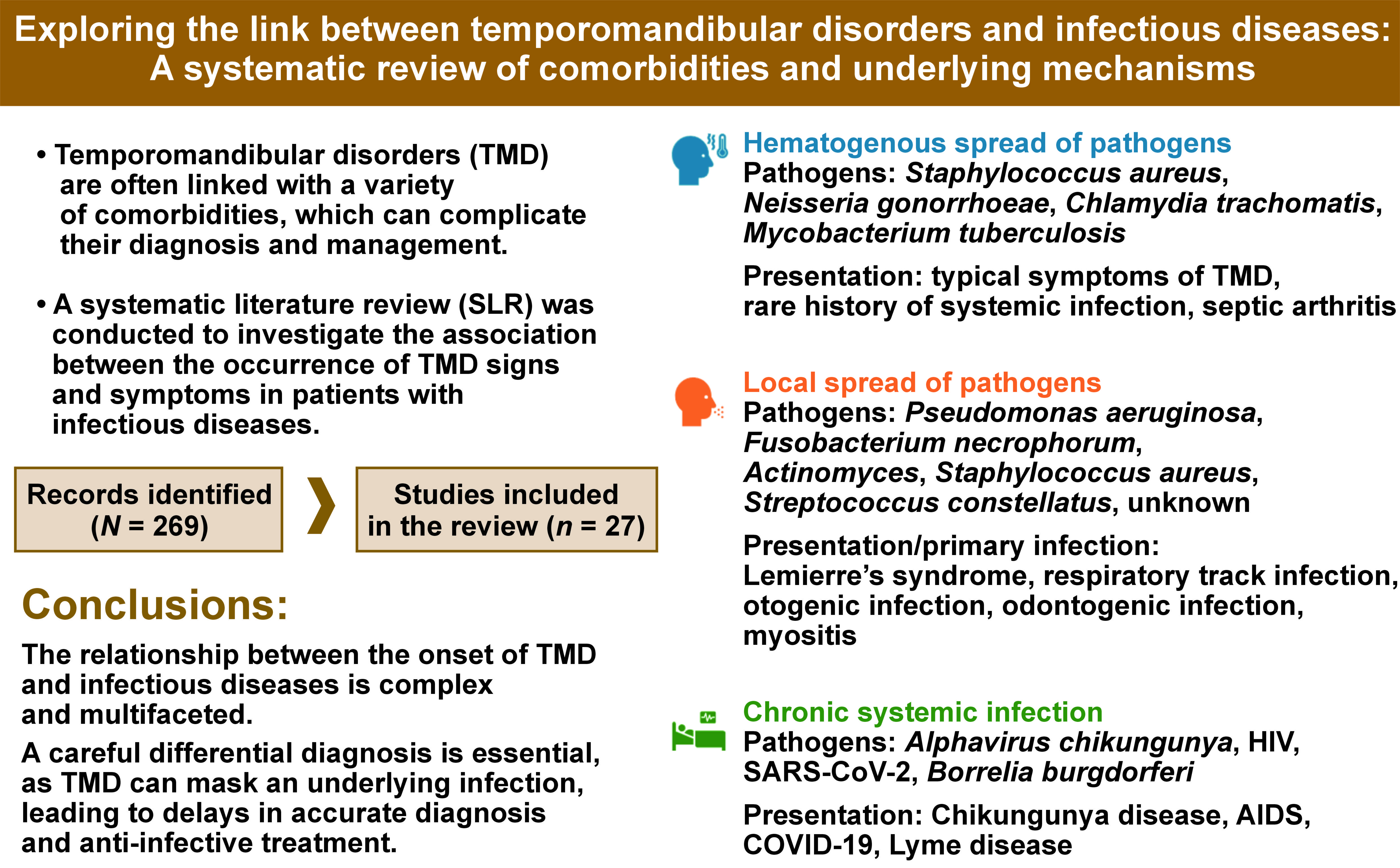

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are often linked with a variety of comorbidities, which can complicate their diagnosis and management. A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted to investigate the association between the occurrence of TMD signs and symptoms in patients with infectious diseases.

The present SLR was carried out in PubMed®. The eligibility criteria were established to include patients presenting with TMD signs and symptoms associated with an infection. The search identified 258 records, of which 27, involving 20,489 patients, were included in the qualitative analysis. Three types of associations were identified between the onset of TMD signs and symptoms and the type of infection. The first association is TMD arising from hematogenous spread of the pathogen to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), the predominant symptoms of which are related to impaired TMJ function. The infection varies in severity and is occasionally asymptomatic, making it challenging to establish a clear connection between pathogen spread and symptoms in the temporomandibular region. Second, TMD resulting from the local spread of pathogens to adjacent tissues within the temporomandibular area were examined. This category included odontogenic infections, upper respiratory tract infections and otogenic infections. Thirdly, TMD associated with chronic systemic infection without arthritis were analyzed, which develop as a consequence of systemic changes due to prolonged illness and/or psychological disorders arising from limited treatment options.

The relationship between the onset of TMD and infectious diseases is complex and multifaceted. A careful differential diagnosis is essential, as TMD can mask an underlying infection, leading to delays in accurate diagnosis and timely anti-infective treatment.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, inflammation, periodontitis

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are often associated with a range of comorbidities, which can complicate their diagnosis and management.1, 2 Recognizing the potential connections between TMD and other conditions is crucial in clinical practice, as the presence of one disorder may indicate an elevated risk of developing another. This association highlights the importance of a comprehensive approach to patient assessment, where clinicians remain vigilant for signs of related conditions. Overlapping symptoms between TMD and their comorbidities can complicate an accurate diagnosis, making careful differentiation essential to avoid misdiagnosis and establish effective treatment strategies. The presence of less common associations between conditions may result in missed diagnoses, potentially delaying necessary treatment if not thoroughly investigated. Being aware of these links enables a more holistic and effective approach to patient care.

Reports from the literature show that patients with chronic diseases are more prone to develop TMD. A systematic literature review (SLR) conducted by Hysa et al., which included 56 studies, reported a prevalence of TMD in rheumatoid arthritis ranging from 8% to 70%.3 Identified risk factors for the development of TMD in patients with rheumatoid arthritis included female sex, younger age, positivity for anti-citrulline peptide autoantibodies, higher disease activity, cervical spine involvement, and the presence of cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric comorbidities. Similarly, TMD symptoms, including pain, tenderness upon palpation of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and masticatory muscles, joint noises (e.g., clicking or crepitus), limited mouth opening, disc displacement, and radiographic changes, are prevalent in spondyloarthritis, with a reported prevalence ranging from 12% to 80%.3, 4 A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by de Oliveira-Souza et al. examined the association between TMD and cervical musculoskeletal disorders.5 The study found that individuals with TMD have reduced endurance of the neck extensors, global and upper cervical hypomobility, and report greater neck disability compared to those without TMD signs and symptoms.5 Silva et al., in a systematic review and meta-analysis, found that the prevalence of degenerative disease in TMD patients with disc displacement is approx. 50%.6 A higher prevalence of the condition was identified in individuals with disc displacement without reduction, at a rate of 66%, compared to 35% in those with disc displacement with reduction.6 Sclerosis and erosion were identified as the most common radiological signs associated with the progression of degenerative joint disease. Clinicians have noted additional associations between TMD and musculoskeletal disorders in daily practice. However, findings from broader analyses remain inconclusive. In particular, the correlations between TMD and generalized joint hypermobility, TMD-related pain following whiplash trauma, and comorbidity with chronic fatigue syndrome have shown inconclusive results, primarily due to insufficient high-quality evidence supporting these relationships.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

The association between TMD and musculoskeletal disorders is largely due to shared biomechanical stress and inflammatory mechanisms that commonly affect joints and connective tissues throughout the body. In contrast, the higher prevalence of TMD in individuals with conditions affecting other body systems is not as well understood. In clinical practice, it has been observed that patients with infectious diseases, especially those with limited treatment options or complicated by a chronic or severe course, frequently report signs and symptoms of TMD. To shed further light on this connection, we conducted an SLR to investigate the association between the occurrence of TMD signs and symptoms in patients with infectious diseases. An additional aim of the review was to explore the variety of pathomechanisms and infection types that co-occur with TMD signs and symptoms or directly lead to their development.

Material and methods

Literature search and eligibility criteria

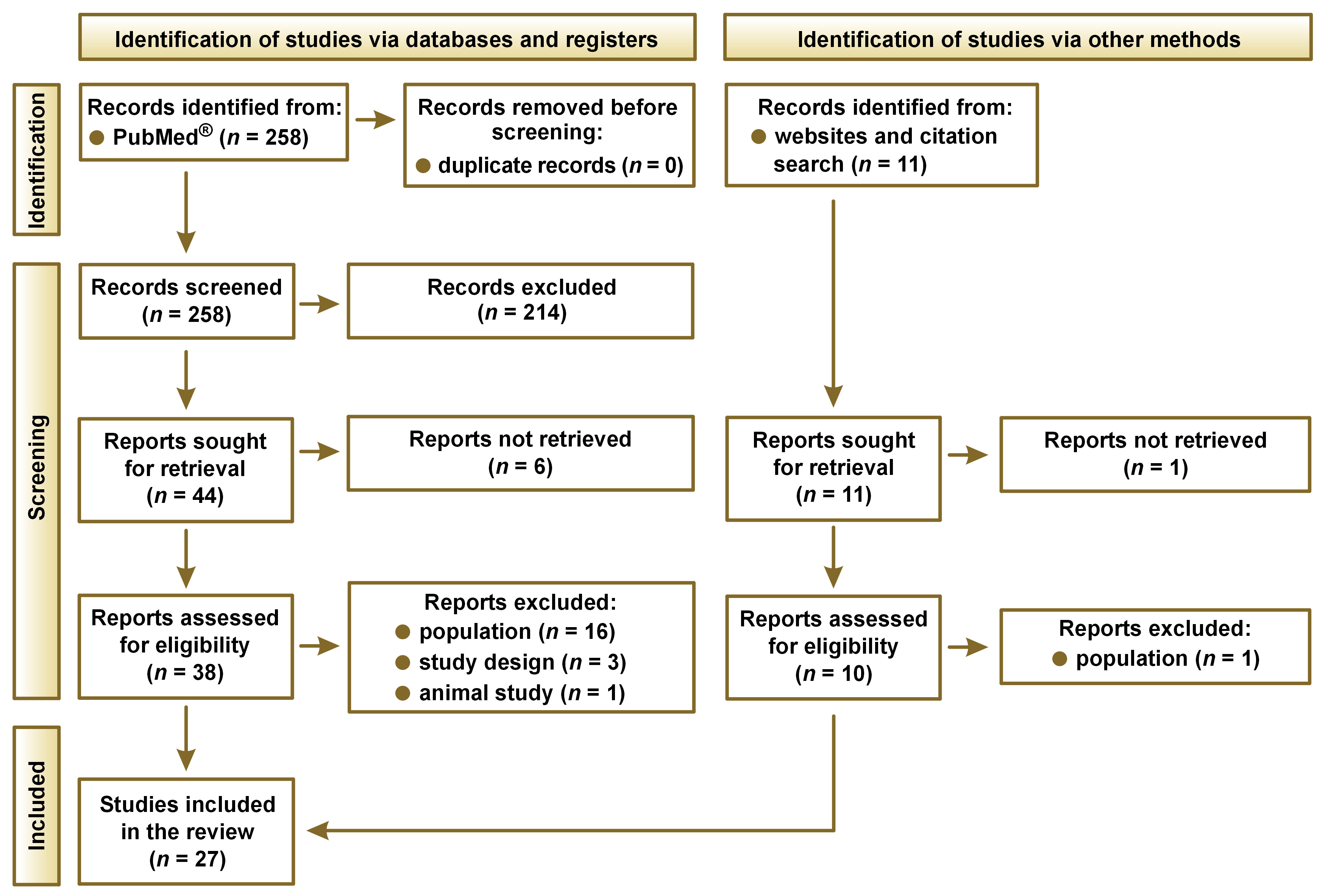

This SLR was conducted in PubMed® and supplemented by a Google search of gray literature, following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement.13 Additionally, references from the identified review articles were investigated to identify relevant articles that were not included in the PubMed® search. The searches were performed on November 2, 2024. The eligibility criteria were defined according to the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study design (PICOS) framework,14 as shown in Table 1. No restrictions were applied to the timeframe or geographical scope. The SLR aimed to include articles written in English.

The eligibility criteria were established to include patients presenting with TMD signs and symptoms associated with an infection. A strict definition of TMD based on the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD)15 was not required, allowing for a broader range of infectious diseases to be considered, in which TMD should be evaluated in the differential diagnosis, including cases outside of dental practice.16

To assess the quality of the included studies, a set of critical appraisal tools developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) was used to assess the methodological rigor of each study.17 This set of checklists was used to encompass all study designs intended to be included in this comprehensive review.

Search strategy

The search string was developed after establishing the eligibility criteria. Two reviewers participated in screening the titles, abstracts and full texts of the identified records. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. A similar approach was used for data extraction. The data was collected and extracted using a standardized approach with templates in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA). The electronic search strategy, based on relevant keywords related to TMD signs and symptoms in individuals with infectious diseases, is detailed in Table 2.

Results

Included studies

The search yielded 258 records, of which 27 were selected for the qualitative analysis.1, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 The process of including identified records is shown in Figure 1, while the list of the identified studies is presented in Table 3.

Summary of the included studies

The SLR included 27 studies involving 20,489 patients. The largest study was a cross-sectional study conducted within the framework of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES).1 The review encompassed 12 cross-sectional studies, 2 cohort studies and 13 case reports.

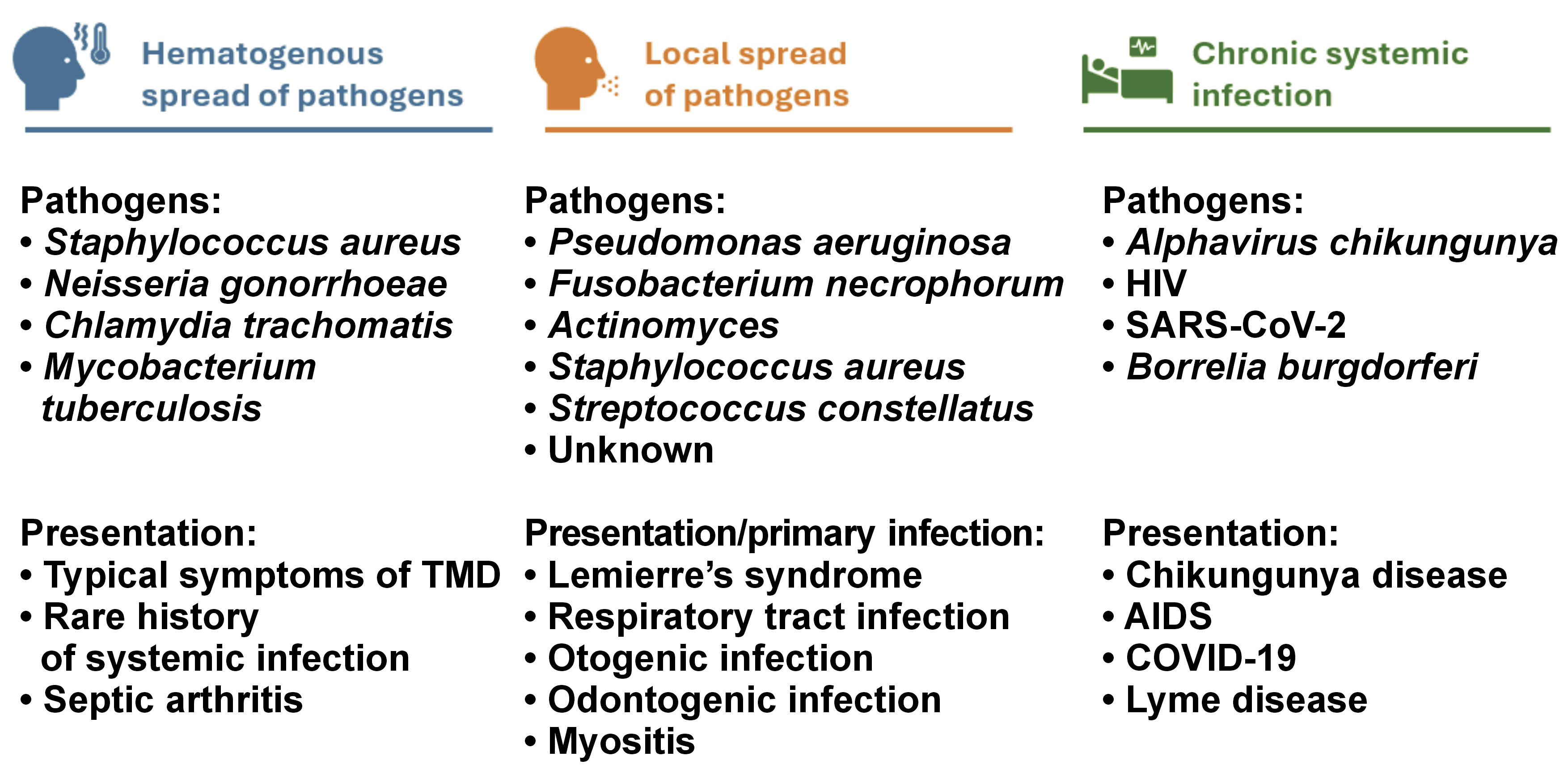

The qualitative analysis identified 3 types of associations between the onset of TMD signs and symptoms and the type of infection (Figure 2):

1. TMD signs and symptoms arising from the hematogenous spread of pathogens to the TMJ: predominant symptoms were related to impaired TMJ function. The infection varied in severity and was sometimes asymptomatic, making it challenging to establish a clear connection between the pathogen spread and symptoms in the temporomandibular region;

2. TMD signs and symptoms resulting from the local spread of pathogens to adjacent tissues involving the temporomandibular area: this category includes odontogenic infections in the oral cavity, upper respiratory tract infections and otogenic infections;

3. TMD associated with chronic systemic infection without arthritis: in these cases, TMD signs and symptoms may develop as a consequence of systemic changes due to prolonged illness and/or psychological disorders arising from limited treatment options.

Quality assessment

The studies were assessed for trustworthiness, relevance, findings, and the risk of bias (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6). Among the included case reports, 11 out of 13 studies (85%) received scores of 7–8, while 2 (15%) received scores of 5–6. The most common shortcoming of these studies was the lack of formally articulated takeaway lessons. Only 1 study was classified as a cohort study; however, it was retrospective and lacked a control group. It received 9 out of 11 points. Among the 13 cross-sectional studies, the scores ranged from 4 to 8, with 7 studies (54%) receiving the maximum score of 8. The most common shortcoming in these studies was the failure to identify and analyze potential confounding factors.

Septic bloodborne temporomandibular arthritis

The TMJ may be the only joint affected in certain bacterial, viral or fungal infections, complicating the differential diagnosis. The infectious agent typically reaches the TMJ via hematogenous spread following a systemic infection or injury.18, 19, 31, 36, 37, 38 Patients may present with symptoms localized exclusively in the temporomandibular region, though some may experience mild symptoms in other joints as well. Due to the TMJ-specific nature of these symptoms, patients are often initially referred to dental clinics for the management of TMD.

Alexander and Nagy reported a case of gonococcal arthritis in a patient who presented with symptoms resembling TMD, including pain in the masseter muscles, muscle spasms and limited mouth opening.19 The patient received symptomatic treatment for 1 month before the correct diagnosis was made.19

Henry et al. observed an increased frequency of serum antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis in patients with internal derangement of the TMJ.31 Among those with positive serology, 86% reported urinary or genital symptoms, though only 14% had a history of sexually transmitted disease, and none had been diagnosed with C. trachomatis infection. The study suggests that serologic testing for antibodies to bacteria associated with reactive arthritis could be valuable in evaluating patients with the internal derangement of the TMJ.31

Tuberculosis, a systemic infection that can affect the cervical lymph nodes via hematogenous or lymphatic spread from a pulmonary source, can also be associated with TMD pathology, even in the absence of active pulmonary disease.18 Prasad et al. noted that while TMJ involvement is rare, they identified only 1 case of TMJ tuberculosis among 165 cases of head and neck tuberculosis.37 Park et al. confirmed that TMJ tuberculosis is difficult to diagnose, presenting a case of a patient who was treated at 2 dental clinics for TMD and osteoarthritis before receiving an accurate diagnosis.36

TMD associated with infections of adjacent tissues

The local spread of pathogens to the temporomandibular region predominantly occurs in immunosuppressed patients, elderly individuals, young children, and those with other chronic systemic diseases, who may be more susceptible to atypical infections. The most common sites of primary infection include the oral cavity, ears and upper respiratory tract.

Ângelo et al. presented a case of a patient with diabetes mellitus and a history of liver transplantation who reported pain and swelling of the TMJ, malocclusion, and erythema in the TMJ area.20 The diagnosis was chronic suppurative otitis media, with a biopsy confirming the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotic sensitivity testing enabled targeted antibiotic therapy, helping to prevent recurrence. Castellazzi et al. reported a case of otogenic septic arthritis in which the patient developed septic arthritis of the right TMJ, with early involvement of the mandibular bone secondary to acute otitis media.24 The patient presented with torticollis, trismus, and right preauricular swelling over the TMJ, and was successfully treated with antibiotics alone.24 Danjou et al. observed that TMJ arthritis can also develop as a complication of necrotizing external otitis, an infection of the skull base typically affecting elderly individuals or those with diabetes.25 Among patients with necrotizing external otitis, 17% developed TMJ arthritis, with P. aeruginosa being the causative pathogen in most cases.25 Infections that spread contiguously to adjacent structures do not need to be concurrent with their sequelae, as demonstrated by Festa et al., who reported a case of unilateral post-infective osteoarthritis of the left TMJ with mandibular condyle resorption.28 A 9-year-old girl was diagnosed, according to DC/TMD criteria, with bilateral myalgia of the masticatory muscles and arthralgia in the left TMJ. These symptoms developed 3 years after the patient had experienced otomastoiditis and periorbital cellulitis.28

Lemierre’s syndrome is characterized by an oropharyngeal infection with bacteremia and suppurative thrombophlebitis of the cervical veins, often complicated by metastatic septic emboli. Its prevalence decreased after the introduction of antibiotics; however, it can still occur in patients without underlying risk factors. In a reported case by Aspesberro et al., a 5-month-old infant developed acute otitis media after 2 days of fever and rhinitis.21 The infant’s condition rapidly deteriorated, presenting with lethargy, swelling in the left retroauricular region, mastoiditis, and TMJ effusion. A biopsy culture identified Fusobacterium necrophorum, allowing for the administration of ceftazidime and metronidazole, to which the bacteria were sensitive.21 Døving et al. reported a similar case involving a man who experienced sudden pain and a sensation of subluxation in the right temporomandibular region while yawning, followed by progressive swelling and tenderness in the TMJ area.26 The patient’s condition worsened over time, eventually leading to Lemierre’s syndrome, characterized by thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein and septic emboli in the lungs. The development of Lemierre’s syndrome was attributed to the local spread of infection by Streptococcus constellatus.26

In a cross-sectional study by Braido et al., 690 adolescents aged 12–14 years were evaluated.23 Painful TMD were identified in 16.2% of the participants and were significantly associated with bronchitis (odds ratio (OR) = 2.5; p = 0.003). The authors attributed this association to the inflammation in the respiratory system.23 Jeon et al. found that patients with TMD more frequently experienced infections in nearby anatomical structures, such as maxillary sinusitis, rhinitis, tonsillitis, and pharyngitis.32 In particular, pharyngitis and sinusitis in TMD patients may serve as risk factors, potentially triggering TMJ symptoms shortly after these infections develop. Klüppel et al. described a case of a woman who developed TMD symptoms and septic arthritis of the TMJ 2 weeks after a throat infection.33 The presence of S. aureus was revealed through culturing methods.33 Park and Auh analyzed data from the KNHANES, a cross-sectional study involving 2,107 individuals (11.86% of participants) who reported one or more TMD symptoms.1 The prevalence of TMD was higher in individuals with rhinitis symptoms, irrespective of their gender and age.1

Yoshizawa et al. presented a case of a patient with an odontogenic infection following a pulpectomy, which had been misdiagnosed as TMD due to overlapping symptoms.43 The patient experienced pain in the temporomandibular region and a restricted mouth opening of 5 mm. The infection ultimately led to life-threatening complications, including meningitis and septic shock.

Eosinophilia-associated myopathies are clinically and pathologically diverse conditions. While some cases may be linked to parasitic or bacterial infections or various systemic disorders, some present with no identifiable etiologic factors and are classified as idiopathic eosinophilic myositis. Aufdemorte et al. presented a case involving a patient with right-sided facial swelling located at the superficial pole of the parotid gland and masseter muscle, accompanied by pain, restricted mouth opening and trismus.22 The patient also had severe periodontal disease. Microscopic examination of the biopsy revealed eosinophilic myositis of the masseter muscle, and needle aspiration identified numerous filamentous organisms surrounded by neutrophils, consistent with Actinomyces species. However, no Actinomyces bacteria were isolated from blood cultures. The patient’s condition improved following intravenous administration of penicillin.22

TMD associated with long-term systemic infections

Chronic infectious diseases are associated with multiple disorders, potentially contributing to wasting of the body and the progression of frailty. Santos et al. investigated a cohort of 198 patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), finding a TMD prevalence of 33.8%.39 The primary symptoms reported were difficulty opening the mouth, muscle fatigue, joint noises, and parafunctional habits. The logistic regression analysis identified an association between TMD and depression (OR: 1.045, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.005–1.087), which can partly explain the presence of TMD in this population.39 Fiorentino et al. highlighted that many patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy report chronic pain and joint pathologies.29 The authors presented a case of an HIV-infected patient who developed severe TMJ pain 8 to 9 months after starting HIV therapy. Analgesic treatment and physiotherapy proved ineffective, and the authors concluded that symptom relief could be achieved by adjusting the therapy, specifically through the replacement or reduction of protease inhibitors. However, the patient was lost for observation.29

Gherlone et al. conducted a study on patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to investigate the co-occurrence of oral symptoms in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) survivors.30 Their findings revealed that 43% of the survivors exhibited salivary gland ectasia, 19% experienced masticatory muscle weakness, 7% had TMJ abnormalities, and 2% reported facial pain. All patients had achieved effective viral clearance, excluding the direct cytopathic effect of the virus as a cause. However, a strong association was identified between salivary gland ectasia and elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of systemic inflammation, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a marker of tissue necrosis, at the onset of symptoms.30 These outcomes underscore the critical role of the innate immune response in the oral cavity.

Lyme disease, the most common tick-borne illness, is caused by spirochete bacteria from the Borrelia species. The condition can lead to large joint arthritis, disseminated infection, or symptoms indicative of peripheral nerve damage. Cases of Lyme disease presenting solely with TMJ symptoms are rare. Weise et al. reported a case of a 25-year-old woman with severe TMD symptoms who was ultimately diagnosed with Lyme disease after undergoing extensive treatment targeting the TMJ.42 The prominence of TMD symptoms contributed to a delayed diagnosis by several years. A cross-sectional study conducted by Osiewicz et al. revealed that 70% of 86 adult patients with Lyme disease were positive for an DC/TMD diagnosis of myofascial pain.35 In another study, Osiewicz et al. compared 76 adult patients with Lyme disease with 54 volunteers without Lyme disease.34 Patients with Lyme disease were characterized by a higher prevalence of osteoarthrosis (17.1% vs. 5.6%; p < 0.001), myogenous pain (18.4% vs. 7.4%; p = 0.059), moderate/severe somatization (73.7% vs. 7.4%; p < 0.001), and high levels of chronic pain-related impairment (15.8% vs. 0.0%; p = 0.002). What is more, the prevalence of depression, ranging from moderate to severe, was found to be significantly higher among patients diagnosed with Lyme disease compared to those without (55.3% vs. 7.4%; p < 0.001).

Chikungunya is an infection caused by Alphavirus chikungunya. The virus is transmitted to humans by mosquitoes. Given the absence of a definitive treatment, the condition becomes chronic. As reported by Fatima et al., patients suffering from Chikungunya virus presented with difficulty in mouth opening and jaw pain.27 The prevalence of oral symptoms in these patients was found to be 74%.27 Simon et al. reported the involvement of the TMJ in 15% of infected patients.40 Staikowsky et al. noted that symptoms suggesting the involvement of the TMJ were more frequent in patients without viremia in comparison to those with viremia (3.2% vs. 1.8%), though this difference was not statistically significant.41

Discussion

Our review indicates that signs and symptoms of TMD are common in patients with infectious diseases. The qualitative analysis identified 3 types of associations between TMD manifestations and the type of infection. In cases where TMD signs and symptoms arise from hematogenous spread of the pathogen to the TMJ, impaired TMJ function predominates. When pathogens spread locally to tissues around the temporomandibular area, the primary infection site may be overlooked. This category includes odontogenic infections in the oral cavity, upper respiratory tract infections and otogenic infections. In patients with chronic systemic infections, TMD may develop due to systemic changes from prolonged illness and/or psychological disorders resulting from limited treatment options. The association between infections and pathologies in the temporomandibular region may not always be immediately apparent, underscoring the importance of a comprehensive evaluation.

The pathogenesis of TMD is not fully understood. Recent research has highlighted the role of elevated inflammatory processes in patients with TMD. Ismah et al. investigated the levels of inflammatory biomarkers in patients who developed TMD after orthodontic treatment.44 They found that the mean CRP value in TMD patients was overall normal, but it was significantly elevated in individuals with intra-articular TMD in comparison to those with other types of TMD.44 Similarly, Zwiri et al. examined the effects of different TMD treatment modalities on inflammatory biomarkers.45 At baseline, the mean CRP level was 2.85 ±1.13, with no substantial changes following treatment. The study revealed no significant impact of treatment modalities on inflammatory biomarker levels.45 On the other hand, CRP levels are elevated in patients with TMD and inflammatory diseases or infections.24, 41 This finding does not facilitate differentiation between TMD and overlapping inflammatory processes of various origins. Inflammatory biomarkers are influenced to a greater extent by the presence of infection and inflammation than by the occurrence of TMD alone, making them less useful for differential diagnosis. The epidemiology, pathogenesis and consequences of septic arthritis of the TMJ have been thoroughly documented in the literature.46, 47 The diagnosis of this condition is straightforward when infection symptoms are prominent and functional impairment of the joint follows pathogen invasion. However, the diagnosis becomes more challenging when infection symptoms are mild or the patient remains asymptomatic. In such cases, a thorough differential diagnosis is crucial to ensure the accurate and timely identification of the condition and prevent unnecessary delays.19, 31 Another key finding from the literature is the relationship between bacteremia and the presence of specific bacterial species in the synovial fluid of the TMJ. Jeon et al. confirmed that S. aureus can cause hematogenous infection of the TMJ, estimating a 55.5% probability of TMJ infection in cases of S. aureus bacteremia.48 This relationship was not observed for other bacteria, such as Streptococcus mitis and beta-hemolytic Streptococcus.

Severe long-term complications can arise from septic arthritis of the TMJ.49 Coleman et al. reported 3 cases of TMJ ankylosis secondary to neonatal group B streptococcal sepsis, in which the patients subsequently developed micrognathia and facial deformities.50 The restricted growth resulting from TMJ ankylosis significantly reduced mouth opening, leading to airway compromise and surgical intervention. Regev et al. reported similar cases in which TMJ ankylosis developed as a consequence of S. aureus sepsis.51 Patients exhibited facial asymmetry with chin deviation to the right, along with mandibular micrognathia and retrognathia. The maximum mouth opening ranged from 2 mm to 15 mm. Sleep apnea contributed to poor sleep quality.51 The present review also showed that TMJ involvement can appear long after systemic infection, a finding that is particularly important in children.24

The association between chronic systemic infections and TMD extends beyond the primary infection and the direct impact of the pathogen on the body. For instance, changes in body composition, such as lipodystrophy in HIV-infected patients, can contribute to TMD-related complications. Paton et al. reported a reduction in superficial facial fat in patients with weight loss, with changes observed in cheek fat, temporal fat, and the compartments of the masseter and temporalis muscles.52 Scali et al. described anatomical changes in HIV-infected patients resulting from facial lipoatrophy and posterior cheek enlargement, often due to parotid gland and masseter muscle hypertrophy.53 Da Silva et al. conducted a cross-sectional study comparing the stomatognathic system function between 30 patients infected with HIV subtype 1, who displayed no signs or symptoms of TMD, and 30 healthy individuals.54 The study showed that the HIV-infected group exhibited relative limitations in masticatory function during chewing. Ultrasound imaging revealed a greater average muscle thickness in the right and left temporal regions at rest and during maximal voluntary contraction. Furthermore, the study noted an increased average thickness in the right and left temporal regions, as well as in the left sternocleidomastoid muscle, when compared to healthy controls. In addition, Umeda et al. observed differences in mandibular condylar bone microarchitecture among individuals living with HIV.55 Positive HIV status remained significantly associated with increased trabecular thickness, decreased cortical porosity, and increased cortical bone volume fraction.55

The chronic nature of the disease has been demonstrated to contribute to the development of mental disorders and somatization in affected patients. A more frequent occurrence of depression was observed in patients infected with HIV and those with Lyme disease.34, 39 Anxiety and depression are often associated with comorbid TMD, adding another layer of connections between those disorders.56, 57 The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted a potential vicious cycle, where the stress and anxiety of contracting a contagious infection and the fear of transmitting it to others may exacerbate TMD symptoms, given the psychological component of TMD.58, 59 This relationship was well-studied in patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic period.60 Anxiety and depression may also contribute to the development of TMD in patients experiencing an acute infection. Askim et al. reported that symptoms of anxiety and depression are associated with an increased risk of bloodstream infections.61 Their study found that severe depression symptoms were linked to a 38% higher risk of bloodstream infection, adjusted for age, sex and education (hazard ratio (HR): 1.38, 95% CI: 1.10–1.73). Somatization may play a significant role during infectious diseases. Osiewicz et al. observed that patients with Lyme disease exhibited significantly higher rates of moderate to severe somatization (73.7% vs. 7.4%; p < 0.001) and widespread muscle sensitization.34, 35 Similarly, Braido et al. found that adolescents with painful TMD reported a greater number of body pain sites in the previous 12 months (4.26 vs. 2.90; p < 0.001) and a higher prevalence of systemic diseases (1.48 vs. 1.18; p = 0.048) compared to those without painful TMD.23 A study by Florens et al. found that, among patients with infectious gastroenteritis, higher levels of anxiety and somatization prior to infection were potential risk factors for the development of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and persistent abdominal complaints.62 Seweryn et al. found that patients with TMD experience high levels of somatization which are associated with elevated levels of central sensitization and greater masticatory muscle pain.63

The present review on the relationship between TMD and infections has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. A high degree of heterogeneity was observed in the study designs and populations, with case reports comprising the majority of the included studies. To better investigate diagnostic challenges, we included studies with varying diagnostic criteria; however, this approach resulted in an escalation of heterogeneity. A paucity of studies reported psychological factors, which are important due to their potential to mediate or exacerbate TMD symptoms in patients with chronic or acute infections that progress rapidly. Additionally, geographic and demographic limitations should be noted, as some infections occur only across specific regions or demographic groups, which may not be representative of all populations and could limit the global applicability of findings. Addressing these limitations in future research would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between TMD and infections. Future prospective and experimental studies should focus on establishing the factors responsible for the development of TMD symptoms in patients with infectious diseases, assessing underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, and evaluating standardized diagnostic criteria for improved clinical management. The exploration of immune response variability in TMD patients with infections could provide more profound insights into the underlying causative mechanisms of this connection.

Current clinical guidelines for TMD do not adequately address infections as a potential background factor or a co-occurring condition.64, 65 However, they emphasize the importance of a thorough examination, including palpation of the jaw structures, such as the muscles and TMJ, which can aid in detecting local infections or rheumatoid diseases affecting the joint.15 To enhance differential diagnosis, we propose incorporating a standardized protocol that includes a detailed medical history focusing on recent or chronic infections, along with a physical examination to identify signs of local inflammation. This approach would improve the early recognition and management of infection-related TMD cases. The present study found that only 6 publications explicitly mentioned using the DC/TMD symptom questionnaire for the identification of patients experiencing TMD symptoms related to infection.23, 28, 32, 34, 35, 39 Conversely, some patients underwent treatment for TMD over an extended period before receiving an accurate diagnosis and appropriate anti-infective treatment.36, 42, 43 The importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between dentists, infectious disease specialists and mental health professionals for the enhancement of the quality of care for patients with pathologies affecting the temporomandibular area is also emphasized.

Conclusions

The present review reveals that the relationship between the onset of TMD symptoms and infectious diseases is complex and multidimensional. The manifestation of TMD symptoms can be attributed to hematogenous and local spread of pathogens. These symptoms can also develop during chronic systemic infections independently of direct pathogen involvement. Careful differential diagnosis is essential, as TMD can mask an underlying infection, leading to delays in accurate diagnosis and timely anti-infective treatment. Such delays may allow uncontrolled pathogens to spread, resulting in long-term health consequences. Conversely, TMD can also develop as an independent disease entity in patients with chronic infections, further emphasizing the critical importance of a thorough differential diagnosis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.